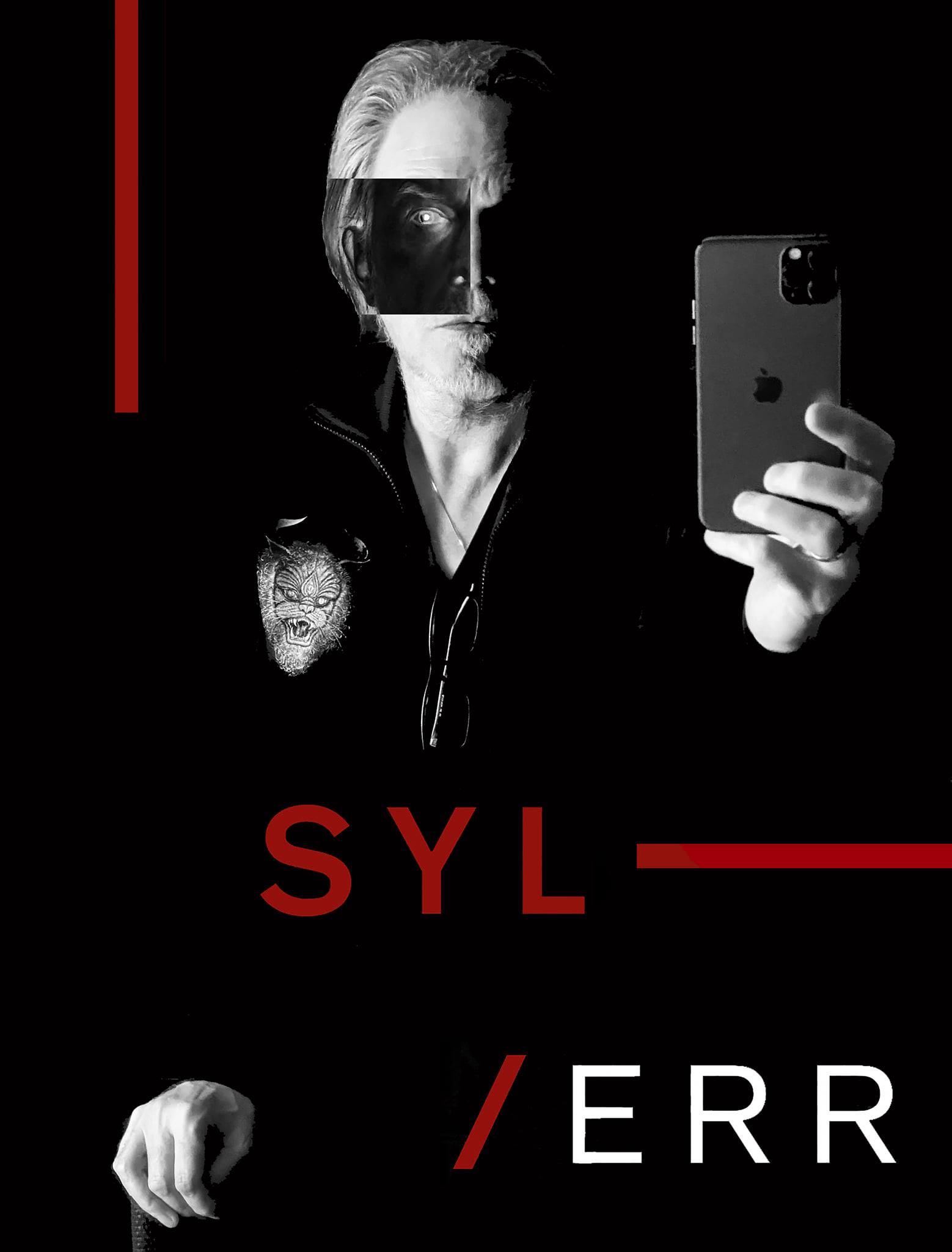

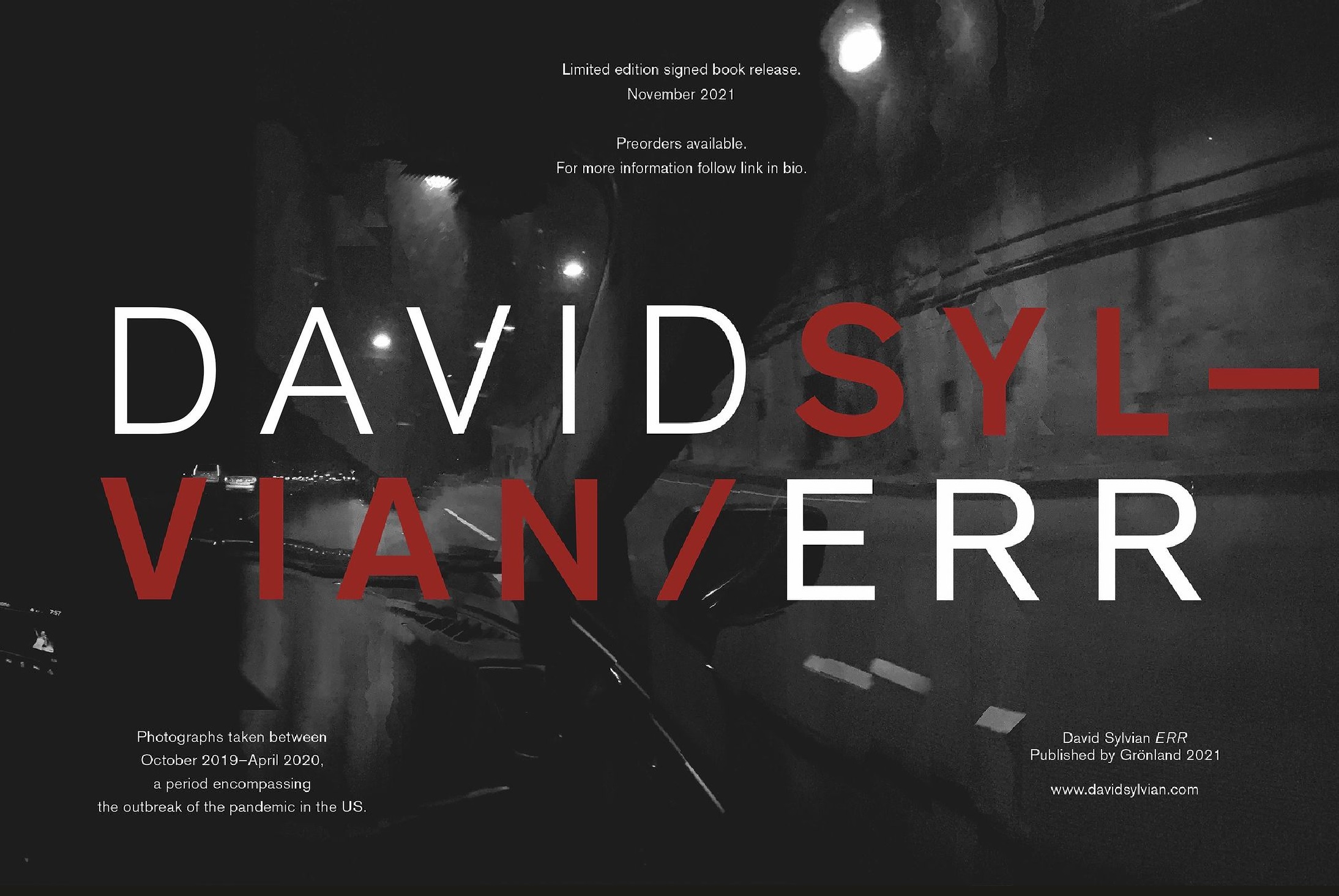

ERR: A photographic essay by David Sylvian. A limited edition publication: 500 copies signed and numbered by the artist. 50 signed, unnumbered copies randomly distributed among the remaining edition. Signed and Numbered Edition: sold out. Standard Edition available to purchase at the Grönland Shop.

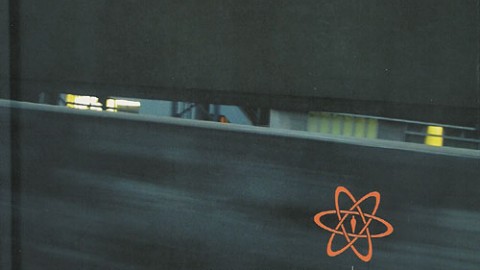

The photographs in this series were taken between Oct 2019–April 2020, a period encompassing the outbreak of the pandemic in the US.

Outside of tonal adjustments, none of the photographs in this collection have been altered in post production.

Be it city or desert, the wilderness sleeps 15 centimeters beneath American roads and many photographers have documented the desolation of these roads through the windscreen of a car. But the photographs in this book, their jaggie violence forever lost in the eternal median of 1 and 0, shatters the American road legend as if it were a cracker. Clearly, this is a new aesthetic made manifest by the emptiness of the digital.

Shinya Fujiwara

Grönland Records announce ERR: A photographic essay by David Sylvian, with text by Shinya Fujiwara and an untitled original poem by Daisy Lafarge.

Publication date: 19 November 2021.

A limited edition publication.

Art direction: David Sylvian. Assistant art direction: Yuka Fujii. Graphic design and typography: Giles Dunn for Punkt, London.

Size: 235 × 340 mm landscape. Extent: 216 pages. Cover: Full dust jacket over foil blocked case cover. Printing: Offset lithography. Binding: Thread sewn book block, case bound.

ISBN: 978-3-00-069573-5

(flip-book images taken from Err microsite)

David’s personal note about the book as published on the Err microsite:

In 2019, sometime in late October, I set out across the US by car in the hopes of finding a place to relocate. I’d just returned from two years in Berlin, Germany and was happy to be on ‘home’ turf if somewhat wistful at leaving behind the kindnesses I’d experienced from a handful of individuals back east.

I’ve driven across the US more times than I can recall. It’s never been an unwelcome chore, rather an adventure, the promise of opportunity, an escape, a delight as I enjoy driving, absorbing the beauty of the country that’s been my home for over 27 years. The remarkably varied nature of the landscape, particularly as one approaches the Rockies from the east, the true oddities one stumbles across manmade or otherwise, the kindnesses of some individuals, the brutal lack of courtesy of others.

I took what’s become my go-to route down 84 to 80, into the 70s, until I reached the magnificence of the Rockies which are initially as blue as the sky so you don’t register them until, a little closer, you realise the cloud formation is sitting atop the blue and slowly the outline appears.

I stayed in New Mexico for a few days scouting possible locations but nothing came of my enquiries so I drove on, into Arizona. As you enter New Mexico and certainly Arizona the horizon broadens to expose a vast expanse of sky and the fleeting cloud formations found there that are so beautifully unique. The temptation to capture them in some form must be an impulse many succumb to. Unless you’ve a magnificent camera of sizable proportions and expense, you’re largely wasting your time. But what’s wrong with wasting your time?

On a previous journey I’d tried to capture something of the landscape on an iPhone. As I panned over the view from the driver’s seat I caught something of the scale of the landscape but also the natural errors that occurred as the technology tried to keep up with the speed the car was travelling. I didn’t dwell too much on these but enjoyed the resulting images. The iPhone I now held in my hands was of a slightly superior technology and, once again, I began to shoot as I drove, not desiring to stop but, through the movement of the vehicle, encourage the errors in the resulting images. I kept shooting on and off until I reached Flagstaff, Arizona, where there was some early snow on the ground. After a couple of nights I moved on and kept shooting through to LA where I was to stay for the next month. On my journeys around town I’d see this or that potential image and attempt to capture it. This process was always hit and miss. I was driving, the iPhone was now larger and more unwieldy to hold in one hand. I was on the move so how much of what first drew my eye would get captured in the frame was incalculable. These elements made the process of taking shots of greater interest not less. I enjoyed the camera’s errors, also the misfiring of what it was I was aiming for, finding I’d captured something partially or entirely different when I returned to my lodgings. This process became something I’d look forward to exploring at the end of each day, scrolling through the shots I’d made, loading them into photoshop to work on the best of them (‘best’ would frequently mean the more difficult to comprehend and therefore a challenge to decipher, make comprehensible).

I discovered early on that by removing colour the images became more legible. I’d work on them in colour and then flip them into black and white and work them further until they appeared complete. I occasionally left a particular shade of red in the finished shot. The interior of the car was red as was the LED display in the rearview. It worked for me aesthetically but also as a reminder of the predominant colour that surrounded me on my journey. After a month in LA I drove to Sacramento where I was to stay another month. The drive north was hit by rain and a little snow. From Sacramento I’d occasionally drop down to my old stomping ground of San Francisco, entering the city by the Bay Bridge. It remains the most beautiful city in all of America. As photogenic as any of the natural phenomena found in the neighbouring deserts.

Once into January 2020 I drove back to LA where I remained for another month. Sacramento wasn’t working for me. As the saying goes: in Sacramento you’re two hours from anywhere you’d really rather be. However, finding a suitable location to live in LA was a far more difficult proposition. After a month I drove back out into the desert and then, upon my return, up the coast to Santa Barbara where I checked into the Lemon Tree Inn. I was given a room which ‘didn’t exist’. ‘It has no number and no one will find their way to it as it sits on the roof outside of the main stairwells’. It sounded good to me. The room which didn’t exist was indeed private and felt sweetly isolated from the world at large. It was while there that news of the pandemic hit hard. Restrictions were coming into play. The housemaids no longer made their rounds to clean the rooms and the restaurant/bar downstairs shut up shop. There were lines at the supermarkets and no hot food to be found. But, being unperturbed by isolation and lack of food, I stayed on until those concerned about my welfare encouraged me to find a home in Santa Barbara until the pandemic was over.

I’d told others we’d be lucky to have things return to a semblance of normality, whatever that might mean, before the summer of 2021. Patience would need to be practiced. I was very at home in my own company needing no interaction with anyone. Nonetheless, I took the advice of those concerned and rented a home I could ill afford next door to my new host. This arrangement wasn’t to last long, however, as the owner rapidly came undone. I’d just kitted the place out for the next year or so but it was unequivocally time to leave. With a refund and all the items I could fit into my small coupé I drove the four hours north to where my ex-wife, Ingrid, was now living to offload most of the items I’d purchased in order to enhance her life there. I stayed in the vicinity for another month as to move on was becoming increasingly unwise.

Ingrid and I met daily, driving around the towns lining Route 1 from Big Sur to Carmel and beyond. She lives in the densest of forests, the light occasionally streaming through the trees, with the ocean a couple of hundred yards away. Throughout the period in Santa Barbara, and now here above the Pacific, I hadn’t stopped shooting whenever on the road. As before, I worked on the photographs by night, reviewing the work come morning. I had returned to staying in a hotel of sorts. Not long after the initial month when the place was near empty, revellers started showing up, maskless, to celebrate graduation or to find release on their vacation in the company of others, enjoying the warmth of the pool, soaking in the hot tub. It wasn’t as if the majority of people wore masks in the hotel corridors and elevators but now the crisis and danger of infection had risen, wellbeing had become more precarious.

I’d failed to find what I was looking for in the way of a home and reluctantly decided to return cross country and, more than likely, head back to Berlin. As the pandemic hit in earnest, the roads in Santa Barbara had seriously begun to empty out. Now, as I drove back across the deserts of California, Arizona, and New Mexico, there was little traffic on the roads outside of haulage trucks: essential workers delivering goods wherever they were needed. This must’ve been around April 2020. As my car tilted northwards on the incline towards Colorado, I hit a wildly explosive thunderstorm which left the sky dark as night. I took my last shots, then put the iPhone away. The light, which had been such an important part of my desire to document the desert, was no longer available to me.

I’d inadvertently made a document of a period that covered pre- to mid-pandemic in the US. The shooting had come to an end as intuitively as it had begun. I continued to make my way towards the East Coast through a Middle America seemingly oblivious to the pandemic and all the darkness it was to bring in its wake. I felt invulnerable. I knew I’d get through this just as I’d recently lived through a number of other traumatic, life-changing events. I missed the light of the west but I thought Berlin must’ve been the answer I was looking for all along. I was as wrong about that as I had been two years prior.

Something I touched upon in an earlier essay is the womb-like existence we experience in the temperature-controlled environment of the car with the audio of our choosing, food and drink as required. We speed through states barely aware of the change in climate in both senses of the word. We become satellites circling the continent with impunity. Simultaneously in motion and motionless. The number and variety of animals lying roadside are too numerous to tally, as are the abandoned cars, particularly on desert roads. On a couple of occasions I was the last car to brake prior to a jack-knifed truck and multi vehicle pile-up. On a road not too far north of LA, a car burst into flames and pulled over onto what there was of a shoulder. Traffic came to a standstill as we watched and waited to see if we’d be exposed to an explosion close enough to cause serious damage. At other times we’d bear witness to the aftermath of a collision with brutalized SUVs, trucks and fragments of vehicles being pulled from the road to allow the flow of traffic to continue unhindered.

Whatever the incident, we’d inevitably pull away at speed with an arrogant impatience, as this wasn’t our tragedy. It may be ours one day of course but today it was some other hapless commuter’s problem. If we stopped for a moment to dwell on the fact, which we actively avoid doing, we couldn’t help but acknowledge that we’re frequently the length of one, possibly two cars from oblivion.

I continued to drive, as if on a loop, for well over a year after the storm on the New Mexico/Colorado border. With the exception of occasional prolonged stays in hotels in one state or another, the microcosm of the interior of my car became my entire world.

I’ve run out of road, setting loose the demons. What, other than apathy, remains?

david sylvian, June 2021