This page contains a compilation of reviews as found online, in papers and magazines.

Latest:

– All About Jazz (Nenad Georgievski januari 2010)

– All About Jazz (John Kelman december 2009)

– iO pages (NL)

– BBC Music Online (UK)

– digg.be (Belgium)

If you have/found a review which is not listed here or a review by yourself? Please contact me to give it a home on this page.

All About Jazz (januari 31th, 2010)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Nenad Georgievski

Singer David Sylvian has had such an unpredictable and diverse recording career that it is interesting to see what will come next. Over the years he has covered a lot of ground, from pop music to gentle, ambient soundscapes, prog rock and fiery, avant-garde experimentation. So it should come as no surprise that his eclectic muse has led him to a new sonic neighborhood with Manafon.

This recording is what we have come to expect from Sylvian: creative splashes of sounds and unique stylings, where various patterns emerge, dissolve, fade and reappear, where the unexpected is always the norm. It is a rough terrain with burbling low frequencies, sometimes unidentifiable and haunting noises, and a sense of unease. It lurches from savage discordance to near silence. But the music is mostly in the background serving as a platform and even more as a challenge for Sylvian to stretch beyond previously settled patterns. His quiet, warm vocals add melodic subtlety and providing depth and drama without adding distraction.

Manafon is a sister album to Blemish (Samadhi Sound, 2003), Sylvian’s previous excursion into improvised music where he teamed up with guitarist Derek Bailey and pushed himself in another creative direction and plateau (a record also shadowed by a divorce and long term relationship break-up). On that record he used the immediacy of writing words over music improvised during a short time, both acts happening simultaneously. For this record he took the same approach as on Blemish but also gathered an impressive cast of various free-improv musicians. The musicians’ unique music excursions can easily be compared to musical approximations of abstract art where each composition unfolds unpredictably. Their interactions add plenty of emotional depth.

Manafon is a strange record where every detail, each fragment, each sensation within, is compelling. It leaves senses bristling with the shock of the new. As a record it sounds more like a theatre play rather than a musical piece with gaps in dynamics taking on the air of a dramatic pause. Sylvian’s beautiful baritone floats around, at times seemingly diving deep. It sure invites loads of thinking and volumes of analysis. The title comes from the name of a village in Wales, a place where poet R.S. Thomas lived and worked and where he wrote his first three volumes of poetry.

Manafon is not an easy record to listen to and many will be severely disappointed. It is not as accessible as many of his other records nor is it easy to warm up to, which means that many may dismiss it upon a single listen or two, never giving it the time it demands in order to be felt, not to mention understood. To get to that point, a lot of patience and spinning would be necessary. Sylvian inspires, scares, confuses, provokes, stirs up the senses and that’s what true artists do. It seems that only those listeners that are dedicated to the artist will probably be patient enough to stay and decode it. This record is not an easy ride but a totally worthwhile one.

All About Jazz (december 6th, 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by John Kelman

Since first emerging as the lead singer of 1980s synth pop group Japan, singer/multi-instrumentalist David Sylvian has turned, in many ways most surprisingly, into one of pop music’s most intrepid explorers. As early as his first solo album, the crooner with a distinctive and intentioned vibrato has been connected with the experimental and jazz scenes, with trumpeters Jon Hassell, Mark Isham and Kenny Wheeler appearing on Brilliant Trees (Virgin, 1986). Since then he’s collaborated with guitarists Robert Fripp, David Torn, Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell and keyboardists John Taylor, RyuchSakamoto and Holger Czukay on albums that range, stylistically, from ambient pop to near-progressive rock. He’s also been involved in multimedia works, including the aptly titled Approaching Silence (Venture, 1999) and, more recently, Naoshima (Samadhisound, 2007) which, along with the collaborative Nine Horses group and its debut, Snow Bound Sorrow (Samadhisound ,2005), reflected a growing interest in the Norwegian and artists including trumpeter Arve Henriksen, and samplers/remixers Jan Bang and Erik Honoré.

Free improvisation and its nexus with more structured composition have always been of interest to Sylvian; even on his last ostensibly pop production, Dead Bees on a Cake (Virgin, 1999), the singer combined his sometimes oblique but visually arresting lyrics with Frisell’s dobro improvisations. With Blemish (Samadhisound, 2003), he took the concept a giant leap forward on a largely solo album, but one where, on four of its eight tracks, late free music guitar pioneer Derek Bailey and guitarist/laptop specialist Christian Fennesz provided Sylvian with improvisations, providing contexts around which he built his austere songs. An album of remixes, The Good Son vs The Only Daughter (Samadhisound, 2004), further demonstrated just how far these sparely constructed compositional ideas could be taken in the hands of creative remixers/recomposers.

Manafon takes the creative process even further, with Sylvian taking a series of free improvisations, performed by a cherry-picked collective of international improvisers, as the starting point, and shaping his words and loosely structured music around them. Other than adding some acoustic guitar and keyboard himself, as well as some sparely overdubbed piano by John Tilbury on six tracks, these spontaneous soundscapes have been enhanced in post-production, but the improvisations themselves remain intact and unreconstructed—as they were, in the moment.

It’s a dark album of stunning beauty; oblique, to be sure, but one that reveals Sylvian to be a continually growing artist whose interests are pure, and now completely distanced from the industry concerns that were an unavoidable part of working with the major labels for the first part of his career. Not that his earlier albums weren’t creative or, the assumption has to be, exact

ly where he was at the time; but unencumbered by outside impositions (even Nine Horses—a pop group to be sure—felt completely honest, a reflection of what the artists wanted without any undue intervention, direct or suggested), with his own Samadhisound label, Sylvian has turned from artful, post-pop crooner to an innovator of the first order.

Even the choice of Sylvian’s collective reflects a breadth of concern that transcends earlier collaborations: from England, Tilbury, AMM co-founder, guitarist Keith Rowe, saxophonist Evan Parker and cellist Marcio Mattos; from Austria, guitarist/laptop player Christian Fennesz, trumpeter Franz Hautzinger, guitarist Burkhard Stengl, bassist Werner Dafeldecker and cellist Mario Mattos; from Japan, no input mixer Toshimaru Nakamura, turntablist Otomo Yoshihide, sine wave artist Sachiko M. and guitarist Tetuzi Akiyama; from the US, live signal processor Joel Ryan. On these nine songs—eight songs with lyrics, one instrumental—a baker’s dozen players come together in various permutations and combinations, from trio to septet, and in many cases represent first encounters. The result is a compelling album of real songs—abstract, to be sure, not of conventional AABA form—that may provide an entry point for those who find the concept of free music unapproachable, by demonstrating that such unfettered improvisation needn’t (and shouldn’t) mean aimless meandering.

The results are stunning. The improvisations—in and of themselves, and without Tilbury’s layered piano—are highly abstruse yet keenly intuitive; seemingly devoid of melody, harmony, rhythm and form. And yet, on “Snow White in Appalachia,” there appear to be (but, given the amount of time Sylvian took in piecing Manafon together, not really) serendipitous moments where a harmonic center suddenly emerges, with as little as Dafeldecker’s single bass note, coalescing this tale of disaster in a way that’s subtle, but dramatic and effective. The album is described, on Sylvian’s website, as an album of ballads, but without any explicit rhythm, the only real reference to conventional balladry is that the ambience is soft, the pace (even without rhythm) slow, and the dynamics subdued and subtle.

At times deeply autobiographical, elsewhere reflecting on external circumstances, Sylvian has also reached a new level of lyrical profundity. Deeply layered, image-seducing but spare poetry reveals more with each subsequent listen, as Sylvian mirrors the music’s intrepid nature. These are songs that may be anything but hummable, but are absolutely memorable—powerful in their allegiance to silence, economy of scale and inherent selflessness. His overdubs are in tune with the improvisations’ gradual evolutions, but act like drawstrings to bring together a number of ideas, that are anything but disparate, into even sharper focus. Tilbury’s contributions are equally vital, Morton Feldman-like in their indeterminacy, and creating a clearer line between the free improvs and Sylvian’s lyrics.

The deluxe edition of Manafon is packaged as a clothbound book with an added DVD that includes both DTS and Dolby 5.1 surround mixes, as well as a PCM stereo version of the CD and hardback book inserts with artwork, an essay and complete lyrics. Most important, however, is the inclusion of Amplified Gesture, a documentary film directed by Phil Howards, with Sylvian as executive producer. With the instrumental music of Manafon as its sonic backdrop, the film (subtitled An Introduction to Free Improvisation: Practitioners and Their Philosophy) explores the emergence of free improv through the words of Manafon’s participants, as well as speaking with AMM co-founder/percussionist Eddie Prévost and saxophonist John Butcher. That Sylvian does not participate as an interviewee in the documentary only speaks to his viewing himself as a beneficiary, rather than a creator, of the free music being discussed—even though Manafon truly deserves a place in the music’s ultimate history.

As austere and economical as the music, Howard leaves the story to unfold entirely in the words of the participants, filmed in black and white and with little visual movement other than that of the musicians speaking, with a few performance stills and very, very spare use of performance footage. What emerges, over the course of Amplified Gesture’s 54 minutes, are many of the foundations of the free improvising scene, which distanced itself almost immediately on its emergence, quite explicitly trying, as Keith Rowe explains, to create something that had never before been heard in the history of music.

An ambitious and, some might say, ostentatious goal, but one of the defining characteristics of all the musicians interviewed is their unmistakable selflessness. Parker describes free improvisers as not trying to command their instruments but, rather, trying to explore them, further describing the act of playing like biofeedback, where as much as the player tells the instrument what to do, the instrument speaks back, and suggests new ideas and avenues of experimentation to the performer.

And undeniable is these musicians’ assertion of the experimental nature of free improvisation. Tilbury contrasts guitarists and violinists, who “sleep with their instruments,” to pianists, who arrive at a venue and are presented with a black box, probably an absolutely new instrument each and every time, with different tuning, different touch, different tone. The audience, too, is a part of the experiment, more involved than they might think, as they provide more than just feedback, but an ambient energy which, in part, drives any free improvisation performed in a concert setting.

That many of these artists come from seemingly conventional backgrounds, growing up with rock and pop groups, bebop, classical music and more, might seem obvious; but, as ever, these intrepidly spontaneous creators may all come from somewhere, but in many cases, as with Keith Rowe, their references become merely one thing more to reject in the pursuit of creating something new. And while Rowe explains how playing a guitar flat on a table creates a certain detachment as opposed to orthodox guitarists for whom the instrument is more an extension of themselves, he’s equally quick to note that it’s impossible to be distanced from life’s experiences. Growing up in wartime England, the sound of exploding bombs became an unavoidable part of who he is and, consequently, the music he makes.

In some ways, Amplified Gesture may be best seen before listening to Manafon. The enlightening insights of the artists involved, with the music playing behind them, makes Sylvian’s ultimate song construction from their improvisations all the more remarkable. But whether experienced before or after Manafon (or not at all: the deluxe edition is a limited one, with a relatively small print run), the great leap of faith that Sylvian took with Blemish has been completely affirmed with Manafon. It’s the inevitable evolution of a significant directional shift that represents, despite sounding unequivocally a part of Sylvian’s larger body of work

, a profoundly beautiful meshing of unfettered, in-the-moment spontaneity and long, careful consideration.

iO pages (NL, november 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Alice Switser

David Sylvian is een raadsel. Een prachtig raadsel weliswaar maar toch… Sinds de begindagen van Japan, waarin hij als frontman met zijn met waterstofperoxide geblondeerde haar menig puberhart – en dus ook het mijne – sneller deed kloppen, is er heel wat veranderd! Het sprookjesachtig mooi verpakte Manafon onderstreept in overtreffende trap hoe ver Sylvian van het pad der ‘gangbare popmuziek’ is afgedwaald. Naar de reden kunnen we alleen maar gissen, dus ik hou het op pure scheppingsdrang waarbij de grenzen vervagen. Dat is niet altijd makkelijk te volgen, maar absoluut oprecht. Werd ons inlevingsvermogen bij Blemish al behoorlijk op de proef gesteld, dit album is dusdanig abstract in zijn avant-gardistische improvisaties dat er van songs geen sprake meer is. De negen stukken worden meer dan ooit gedragen door die zo bekende, weemoedige bronzen stem. En dat terwijl zijn begeleiders, voornamelijk kanonnen uit bovenstaande stroming, in hun aperte instrumentale naaktheid eerder uit lijken te gaan van het begrip ‘anti-muziek’. Er klinken zo nu en dan aanzetjes van gitaar, bas en piano, maar allemaal even kaal en ondergeschikt aan Sylvians zanglijnen en het gesproken woord. Dat doet hij als vanouds bijzonder mooi en ingetogen, maar verder regeert hier het minimalisme: geen geluid teveel en zelfs de tikken en kraakjes zijn gedoseerd.

Rest de vraag: voor wie is dit bedoeld? Hierover zullen zelfs de meest verstokte liefhebbers zich minstens één keer achter de oren krabben. Als je in de luxe positie verkeert om hier eens vrijblijvend, maar zorgvuldig naar te luisteren, is dat de tijd zeker waard. Voor mij persoonlijk blijft het daar echter bij. Het is dat ik overtuigd ben van ’s mans integriteit, want bij menig ander zou ik Manofon waarschijnlijk afdoen als pretentieuze navelstaarderij. Info: www.davidsylvian.com.

BBC Music online (UK, 10 December 2009)

If only all so-called artists could display this courage.

by Chris Jones

Anyone who still harbours dreams of David Sylvian’s return to the faux-Ferry new romantic stylings of yore, leave the room, now. Describing a career arc that’s elegantly swooped through coffee table ambience towards a “devotion to creative discipline”, he now inhabits (like Scott Walker) that most rarefied of zones where artistic credibility eschews commercialism in any form. Ironically, the result of such a determinedly stoic path meant that 2005’s Nine Horses project seemed almost disappointingly mainstream. Manafon is, by no means, such an easy listen.

Almost constructing music in reverse, his last major solo release, Blemish (2003), was stripped bare of just about everything except Sylvian’s voice and the late Derek Bailey’s rattling guitar strings. Only when Sylvian turned the work over to the remixers on The Good Son Vs The Only Daughter did anything really resembling songs emerge.

Superficially this is the same minimal fare. Manafon ploughs a confrontational furrow. Sylvian’s current modus operandi begins with him capturing his voice, bravely naked and unadorned except by pitch-shifted harmonising. He then invites collaborators across the globe to add layers of meaning.

Here the sparse chittering of Bailey is replaced with a richer cast of notables, including the free jazz of Evan Parker’s saxophone, John Tilbury’s questioning piano, Werner Dafeldecker’s earthy double bass and the dusty, ambient scratch of Otomo Yoshihide’s turntables. And as if this cast didn’t suitably underline Sylvian’s place as pop star reborn as cutting-edge experimentalist, he replaces the angular prod of Bailey’s guitar with AMM legend Keith Rowe, as well as Blemish’s other notable player, Christian Fennesz.

Close listening reveals more intricacy, intimating a stronger ensemble vibe while still leaving the door ajar for chance and accident. And while, lyrically, it still relies on a third-person recital of loss and denial, Sylvian does manage to pack some humour and self-effacement into the narrative.

Above all, the album’s autobiographical bent describes a man who may seem wilfully puritanical and harsh, but whose methods yield immense beauty for the listener. The title track – based on the village where the poet RS Thomas lived – is an analogy for a figure with whom Sylvian indentifies when he describes him as “an insufferable individual” who is “upholding morals and values that even he struggles with when it comes to believing in their efficacy”.

Manafon is a brave, disconcerting and terrible document. If only all so-called artists could display such courage.

digg.be (Belgium, 2 November 2009)

Voor Digg*ers van: veeleisende, minimalistische muziek.

by Nick Delafontaine

Thom Yorke en Jeroen Brouwers hebben iets met Japan. En ik heb iets met Thom Yorke en Jeroen Brouwers. En met David Sylvian. Na het beluisteren van ‘Manafon’ zelfs nog net iets meer. En tegelijk net iets minder, want we kunnen ons niet voorstellen ‘Manafon’ elke week op te zetten. ‘Manafon’ is namelijk zo’n album dat je ziel en lijf compleet leegzuigt. Daarin staat het niet alleen in het werk van David Sylvian. Ook het genre waarin het gemaakt is – strikt minimalistisch – is maar een van de vele stijlen waarin Sylvian zich in de loop der jaren in bekwaamd heeft, zoals jazz, avant-garde, ambient en progrock.

Op ‘Manafon’ is een allegaartje aan instrumenten aanwezig – zowat alles dat geen drum is, zit erbij – maar al die instrumenten horen we vooral niét. Af en toe eens een riedeltje gitaar op de achtergrond, obligaat maar raak zoals in ‘The Rabbit Skinner’, maar veelal verloren in het ijzige niks, enkel voortgedreven door Sylvians jeremiërende stem. En dan nog blinkt ‘s mans prominent aanwezige stemgeluid vooral uit in afwezigheid. Zo snijdt het van alle overbodigheden ontdane ‘Small Metal Gods’ – een mens zou wat anders verwachten – meteen diep door je zielenslaap, al gebeurt er eigenlijk volstrekt niks, op Sylvian na die de tekst

bijna in parlandostijl voordraagt.

Vaak hoeft het ook niet meer te zijn dan dat. ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ is een dystopie, waarbij we de godvergeten geluiden die eruit voortspruiten zo in Metropolis kunnen plaatsen. Tel daar bij op dat Sylvian je strot met zijn lage bas volledig dichtknijpt en dat de slechts achteloos aanwezige gitaar je in ware Max von Sudowstijl de dood in gidst, en je weet dat je een kostbaar kleinood in handen hebt.

Een van onze absolute favorieten is ‘Emily Dickinson’ (voor wie haar niet kent: het had evengoed Joni Mitchell kunnen heten), dat nog het best omschreven kan worden als ‘sax met klopgeesten’. Maar dan wel een sax die erg fijn gebruikt wordt en die voor het eerst en tevens bijna voor het laatst voor afwisseling en verstoring zorgt in het domper gestemde ‘Manafon’. Verder tekenden we enkel op het afsluitende titelnummer nog een dergelijk zomers geluid op – nou ja, zomers in deze context dan toch. Sylvian had zich vast thuis gevoeld bij grote romantici zoals Coleridge en Wordsworth.

Ook erg goed bevonden werd ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’. Wie een ode aan deze of gene veldmaarschalk verwachtte, mag van een kale reis terugkomend rechtsomkeert maken. Sylvian doceert immers elf lange minuten over miskenning, en als hij het woord ‘Melancholy’ orakelt voel je de moed ook letterlijk in je schoenen zinken. Het nummer duurt misschien iets te lang en verliest zijn spanningsboog wat te veel in overbodige rariteiten als lichte scratch en bliep, maar een kniesoor die daar om klaagt.

Rest ons nog te zeggen dat ook ‘Snow White In Appalachia’ weliswaar meer van hetzelfde is, maar eveneens op erg hoog niveau koerst en met iets meer aankleding verzorgd is. Het opent met een noiseintro, als was het hier Sonic Youth, en klinkt totaal uit de toon geplaatst maar er tegelijkertijd toch net weer in vallend.

We hebben er echter alle begrip voor als u dit album na zes minuten terug naar afzender zou sturen. ‘Manafon’ is een moeilijke plaat, waarmee we niet doelen op een vereiste dosis muzikale intelligentie, maar veeleer op zin en tijd om er in te investeren. Als u ons vraagt of wij daartoe bereid zijn dan antwoorden wij met een krachtig ja. Vier sterren, niks te veel.

The Straits Times (Singapore, 23 Oct 2009)

Songs for the avant garde

4 out of 5 stars

Trivia pursuit’s morsel for the literarily inclined: Manafon is the name of the village in which the late Welsh poet and Anglican clergyman R.S. Thomas worked and lived

By naming his latest record after the residence of the introspective writer, David Sylvian signals his cool-eyed empathy with loners and survivors who withdraw from the dog-eat-dog 21st-century world order.

It may well describe his own artistic trajectory from his pop-rock/New Romantic germination as the frontman of Japan to his solo career as an experimenter working under his own name and a series of monikers such as Nine Horses and Rain Tree Crow.

Manafon, in this light, is the apotheosis of his avant-garde commitment.

Recorded in Vienna, Tokyo and London, it brings together a coterie of luminaries, ranging from Austrian electronic whiz Christian Fennesz and British electro-acoustic expert Keith Rowe to pianist John Tilbury and Japanese musicians Toshimaru Nakamura, Tetuzi Akiyama and Sachiko M.

The result is a pared- down counterplay between improvisation and composition, a minimalist narrative through noise and silence, all linked by Sylvian’s smoky, silky baritone that sounds both comforting and strangely godly.

It may sound forbidding on paper, but the effect is resonant.

He calls it “a completely modern kind of chamber music”, and the title track Manafon “a description of a man of faith, who struggles with that faith, who imposes an order on the external world in the hope of finding it internally”.

This struggle between salvation and desolation can also be espied in the guest spot of improv saxophone legend Evan Parker in the sparse track Emily Dickinson; his soprano gathering emotional heft amid snow or desert as chant-like echoes float by.

The centrepiece, the 11-minute epic The Greatest Englishman, feels like a shadowy, untold biography where musical lines are cut up, with Sylvian calmly delivering the words of a man whose existence is “such a melancholy blue, or a grey of no significance”.

Rigas Laiks (Riga Latvia, 11 november 2009)

Mēs visi mirsim un drīz

Ilmārs Šlāpins

Deivids Silviens ir atmosfērisku noskaņu meistars, kas nebaidās atkailināt savu balsi un sajūtas, paslēpdamies vien mīklainu tēlu un zīmju pilnos tekstos. Turpinot virzību uz aizvien izplūdušāku skaņdarbu struktūru, nesteidzīgu un smagu melodisko zīmējumu, kas bija jaušams jau viņa iepriekšējā albumā “Blemish”, šeit Silviens izmanto vēl plašākus un drūmāku toņu otas triepienus. Veidu, kādā tiek rakstīta šāda mūzika, ir grūti definēt, līdzīgi strādā Skots Volkers, arī viņa dziedāšanas maniere ir tūlīt pazīstama un neatdarināma. Lai arī albuma ierakstos piesaistīti vairāki izcili mūziķi, kas pazīstami kā brīvās improvizācijas entuziasti (Evans Pārkers, Fenešs, Sačiko M.), tas tomēr nav aizraujošu džeza dialogu krājums. Tas ir viena, vientuļa un strauji novecojoša cilvēka pārdomu pieraksts. Vairāku dziesmu pamatā ir dzejnieku Emīlijas Dikinsones un Ronalda Sjtuarta Tomasa frāzes vai tēli, Manafona ir ciemats Velsā, kur kādu laiku Tomass bijis vietējās draudzes mācītājs. Bieži vien viņa baznīca svētdienās bija tukša un sprediķa vietā viņš sēdējis tur pilnīgā vientulībā, rakstot dzeju.

Blurt Online (USA, 17 september 2009)

David Sylvian – Manafon

9 out of 10 stars

On Manafon erstwhile Japan frontman David Sylvian seems to have crafted something both improvisational and quiet, bruising, distant and avant-garde yet not without melody or easily contained mood shifts. And as different as any of his recent works are from those of his past.

The tune “Small Metal Gods” is hum-able, plucked and tender – filled with the clicks and wood bumps only the best of Manfred Escher’s ECM’s vinyl recordings might feature. There’s even something queerly political about “SMG” – its mentions of laborers at no pay – itself a unique bit of play from a man not usually known for such. There’s a lot of that wry wriggling in his lyrics here; Emily Dickenson, dead rabbits, even the things that fill his 11-minute “The Greatest Living Englishman” – a life of “melancholy blue, or a grey of no significance.” This may be suicide but it seems so blackly funny I can’t help but snigger.

Perhaps that’s because Sylvian’s vocals have a softer brighter flutter to it than in the past, a voice that finds sympathy in the sub-tone squints of a tenor saxophone, the abstract twinkle of a piano’s Satie-esque still life and the squeak of strings from an acoustic guitar to a wayward violin. And that voice makes the burr behind the desperate poetry sound that much more fleeting, ample and odd rather than merely maudlin. The “exhaustible indifference” he sings of in “Snow White in Appalachia” can be heard in his own hollowed out hoot, accompanied by the barely there blip-and-scratch of a tape-loop gone mildly wonky. That’s more fun than I imagined from Sylvian.

Standout Tracks: “Small Metal Gods,” “The Greatest Living Englishman,” “The Rabbit Skinner” A.D. AMOROSI

La Vanguardia (Spain, 7 october 2009)

Canciones abstractas

by Ramon Surio

El actual sonido de David Sylvian, el otrora líder del grupo Japan, ha sido calificado de “spoken folk de cámara improvisado”. También se podría hablar de canciones abstractas, en e sentido que conjuga de manera brillante música experimental y una emotiva voz que esculpe melodías prácticamente sin cantar, apenas traspasando la declamación recitada, hasta crear una sensación de suspense impactante. Para lograrlo se ha rodeado de un elenco internacional de improvisadores, entre los que destacan Christian Fennesz, Evan Parker, Keith Rowe y Otomo Yoshihide, cuyas intrincadas atmósferas electroacústicas son el substrato sobre el que Sylvian desgrana sus lánguidas melopeas, asumiendo con su envolvente voz todo el protagonismo. Es una lírica que le sirve para mostrar su desilusión con los gurús en Small metal gods, su sentido irónico en The greatest living englishman o su rendida admiración al poeta galés R.S. Thomas en el tema que titula el disco. Es la culminación de un interés por la música improvisada –con el muy loable precedente de Blemish (2003), junto al guitarrista Derek Bailey – que se remonta a los días de sus colaboraciones con Robert Fripp y Holger Czukay.

HUMO (Belgium, 6 october 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by cv

4 stars

Consumententip: of u vindt dit pretentieus gepriegel van iemand die geen moer geeft om wat de buitenwereld van hem denkt, of u beseft dat ‘Manafon’, de nieuwe plaat van David Sylvian, een avontuur zonder weerga is.

Al van toen hij het Jonge Blonde Uithangbord van Japan was, meer dan dertig jaar geleden, verdeelt Sylvian de muziekgemeenschap in beate volgelingen en rabiate tegenstanders. Sindsdien is het groepje volgelingen steeds kleiner geworden, zeker na het uiterst minimaal gearrangeerde ‘Blemish’ uit 2003.

Voor ‘Manafon’ heeft Sylvian wél weer een pak volk naar de studio gehaald: de credits signaleren cello, sax, bas, gitaar, trompet, turntables en piano (noteer: geen drums). Maar wie hoopt dat hij terugkeert naar de kamerpop van bijvoorbeeld ‘Secrets of the Beehive’ uit 1987, is eraan voor de moeite.

De songs op ‘Manafon’ zijn kaal, en de muzikanten krijgen zelden de kans om een melodie te ontwikkelen. Alle instrumenten lijken wel door de laptop van Christian Fennesz gefilterd, wat een ruwharig klankentapijt oplevert. Zonder franje, maar zéker niet zonder ziel: dit is vitale muziek van een man die bij een eerste kennismaking in zichzelf gekeerd lijkt, maar bij nader toehoren een universele zeggingskracht prijsgeeft. Daarin doet hij enigszins denken aan Scott Walker, hoe verschillend hun muziek verder ook klinkt. Nog één keer schoot ons een andere grote naam te binnen: de zangmelodie van ‘Snow White in Appalachia’ herinnert aan John Cale.

Meer dan we van Sylvian gewend zijn, zit zijn stem prominent vooraan in de mix. Daardoor slaan de songs over de dood, miskenning (‘The Greatest Living Englishman’), verdwenen onschuld en de bepaald onplezierige toekomst die ons te wachten staat (‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’) als natte dweilen in je gezicht. Af en toe flakkert er een eenzaam vlammetje op (de sax van Evan Parker in het voorts gure ‘Emily Dickinson’, of het door Sylvian zelf gezongen koortje aan het einde van ‘Small Metal Gods’), maar dat dooft snel weer uit.

Een paar weken geleden wankelden wij compleet groggy de bios uit, midscheeps getroffen door ‘Antichrist’, de nieuwe film van Lars von Trier. Pas veel later, toen we weer een beetje bij onze positieven waren, begrepen we wat Lars had willen zeggen: je moet door de hel gaan om in de hemel te komen. David Sylvian laat horen hoe dat in muziektaal klinkt: somber, overrompelend, en vier sterren waard.

ABC Nyheter (Norway, 22 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Paul A. Nordal

4 out of 6 stars

(ABC Nyheter): Det er aldri lett å forberede seg på hvilken retning veteranen David Sylvian (51) tar når han gir ut nye plate.

Forløperen til årets utgivelse, «When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima» (2007),

var en plate som inneholdt lydkulisser i stedet for tradisjonelle låter, mens prosjektet Nine Horses fra 2005 og utover, hvor han jobbet sammen med sin gamle Japan-makker, broren Steve Jansen og Burnt Friedman (men som også inkluderte skandinaviske gjester som Stina Nordenstam og vår egen Arve Henriksen) var musikk som gamle fans av Japan og de tidligste soloplatene lett kunne nikke gjenkjennende til. Underlig landskap

På årets «Manafon» tar David Sylvian et dypdykk tilbake til sine mest eksperimentelle jazzrøtter, og serverer et lavmælt og improvisert jazz uten perkusjon i et høyst underlig musikalsk landskap, men hvor Sylvians alltid like forførende stemme er det bærende element.

Kanskje ikke overraskende med tanke på alt David Sylvian har involvert seg i opp gjennom årene, men så tar han heller ikke den enkleste stien for å nå tilbake til sine gamle tilhørere.

«Manafon» er en jazzutgivelse som antagelig vil fortone seg noe krevende for gamle Japan-fans. Stemmen er imidlertid den samme som den gang, og med tålmodighet er det faktisk stor gevinst å hente for de som fremdeles lar seg gripe av multitalentets mange påfunn. Ikke øvd inn

David Sylvian og hans medmusikanter på dette albumet hadde ikke øvd inn en tone da de møttes i studio for å spille inn de ni låtene som til slutt skulle bli «Manafon». Ingen låter var heller skrevet på forhånd, så her snakker vi improvisasjon i alle ledd. Og det merkes.

Tekstene til Sylvian er også skrevet mens han arbeidet med innspillingen i studio, men skal være inspirert av den walisiske poeten R.S. Thomas. Tittelen på albumet skal også være navnet på en liten landsby i Wales hvor denne forfatteren har levd, mens hver enkelt låt speiler små historier med handling lagt til dette litt mystiske skogslandskapet.

Som nevnt er det krevende for den menige lytter å sette seg inn i Sylvians uvanlige og ikke akkurat hverdagslige musikkunivers. Låtene smyger seg nærmest av gårde, her og der krydret med rare elektroniske eller mekaniske lyder som får en til å lure på om noe er galt med avspillerutstyret eller høyttalerne. Men, som seg hør og bør i Sylvians kretser, så skal det selvfølgelig være sånn. Alt har en slags mening. Ulikt det meste

Oppsummert er ikke resultatet til å kimse av, men «Manafon» er nok likevel neppe en plate for alle, ei heller for gamle svorne fans. Men som i mange andre sammenhenger, så må man satse på å vinne, så hvorfor ikke gi «Manafon» en sjanse likevel? Dette er nemlig et album som garantert ikke høres ut som noe annet du har i samlingen fra før av.

Ultrapop (Norway, 30 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Ultrapop

David Sylvian, vår venn eller uvenn? Det er sannelig ikke helt lett å vite, ikke slik han ter seg år etter år, album etter album, skritt for skritt stadig mer introvert og krevende. Sylvian stiller strenge krav til den som gjerne vil følge ham, verken fem flate eller ti tynne skjenkes den mengde tilhengere som en gang for veldig lenge siden flokket seg rundt ham. For slik vil han ha det.

“Manafon” bidrar ikke til å løse den knute, frieri til alminnelige lyttere er overhodet ikke på tale. “Manafon” kapsler ikke en éneste, med unntak for svært vage antydninger i innledende “Small Metal Gods”, komposisjon, melodi, låt – hva man nå enn foretrekker å kalle det – i tradisjonell forstand. Refreng? Selvsagt ikke. Vers? På en måte, om godviljen legges til.

“Manafon” er på det musikalske plan ren improvisasjon, skapt og festet til tape i nuet, i ettertid sakset og limt til en redigert masse. Her er gitar, piano, saksofon, cello, turntables og laptop; men ingen spiller noe av konkret eller håndgripelig karakter. Ei heller holder albumet perkusjon eller rytmikk av noe slag, aldri åpnes det rom for løft eller forløsning. Det klimpres, strekkes strenger, blåses korte toner, klikkes, skurres og illuderes hakk i plate. En strøm av lyder og avbrutte toner, helt der nede, veldig dempet. Organisk jazz, folk, natur. Eventuelt kun dill, avhengig av øret som hører.

Sylvians stemme – noe eldre og med litt mer rust, men fortsatt umiskjennelig – er mot bakteppet av lyd platens bærende element. Der musikken isolert hørt favner en slags abstrakt poesi, er Sylvians vokal og de strofer han formidler det konkret poetiske tilsvar. Uten lyrikk ville “Manafon” fremstått som en uhørbar lidelse, med og hørt i sammenheng gir de snaue femti minuttene med ett en mening. Vokalen og tekstene fanger den fokus som musikken i de fleste normale tilfeller – for popdisipler – ville gjort. Denne og disse mørke på grensen til misantropi, med mindre den mann som “Manafon” utforsker er Sylvian selv. I så tilfelle en konfronterende selv-misantropi, som ‘Here lies a man without qualities’… ‘Don’t know his right foot from his left’… ‘I’m better off this way’. Etc. i mengder.

Det er vanskelig, og føles også unaturlig, å høre en plate som “Manafon” i vante, daglige omgivelser. Den hører på sett og vis ikke hjemme i det moderne hus, omgitt av støy og ståk fra alle kanter. Kan hende vil den fungere optimalt et sted med utsikt, på en stubb på en knatt i en skog. Sånn ved en, for all del, lett nedstemt og tankefull dag. Hva som uansett er sikkert er at ro og konsentrasjon er dyd av nødvendighet i forhold til albumet.

Men er “Manafon” virkelig bra eller er det selvbevisst / -opptatt skrap, lurte du kanskje på? Ingen anelse, er mitt svar. De flere vil nok erfare å sakte krepere av kjedsomhet, de færre vil under rette forhold finne “Manafon” å være fascinerende forunderlig. “Manafon” tilegnes i større grad enn mye annen musikk på eget, og bare eget, ansvar.

Gonzo (28 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Robert Muis

Ik ken mensen die een hekel hebben aan de stem van David Sylvian, maar zijn platen nog konden waarderen vanwege de fijne melodieën en mooie sfeer. Zij hoeven ‘Manafon’ niet aan te schaffen. Sylvians kenmerkende stemgeluid is nadrukkelijk, zo niet centraal, op de nieuwe cd. Bij beluistering zou je kunnen denken dat hij zijn teksten heeft gezongen en vervolgens een keur aan collega’s er de muziek bij heeft gespeeld. Zoals Peter Bruyn in zijn artikel over Sylvian in Gonzo (Circus) #93 uitlegt, is echter eerst de muziek in meerdere improvisatiesessies tot stand gekomen. Daartoe nodigde de zanger, muzikant, componist en in dit geval dus ‘klankregisseur’ Sylvian een groot aantal mensen uit de improvisatiehoek uit. Niet de minsten, ook: Burkhard Stangl, Michael Moser, Otomo Yoshihide, John Tilbury, Franz Hautzinger, Evan Parker en Christian Fennesz, om er een aantal te noemen. Uit de gecreëerde abstracte klanklandschappen

koos Sylvian de stukken die hij kon gebruiken en schreef daarbij zijn teksten. Mooie teksten, overigens. Niet bijzonder vrolijk, zoals we van hem kunnen verwachten, maar enige ironie klinkt er wel. Hij is ver weg van de popsongs van Japan, of zelfs de latere cd’s als ‘Secrets of the Beehive’ en ‘Dead Bees on a Cake’. Muziekmelodieën en zanglijnen die je makkelijk meeneuriet zijn er niet echt. Sylvians zanglijnen geven slechts minimale melodieën; de instrumenten leveren geen melodie en geen ritme. Wat niet wil zeggen dat er niets kan beklijven: telkens herhaalt zich in mijn hoofd een tekstfragment uit ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’, ‘125 Spheres’ of het titelnummer. Wat een schoonheid en kracht spreidt deze cd ten toon. En al is de stem nadrukkelijk, de bijdragen van een groot aantal muzikanten uit de improvisatiehoek –– draagt absoluut bij aan de pracht. De lijn die hij heeft ingezet met ‘Blemish’ trekt Mr. Sylvian indrukwekkend door.

Twente uit de kunt, Twentsche Courant Tubantia (1 october 2009)

David Sylvian maakt onalledaags, maar subliem album

by Theo Hakkert

Oud-zanger van Japan ontstijgt op Manafon aan alle genres en zichzelf.

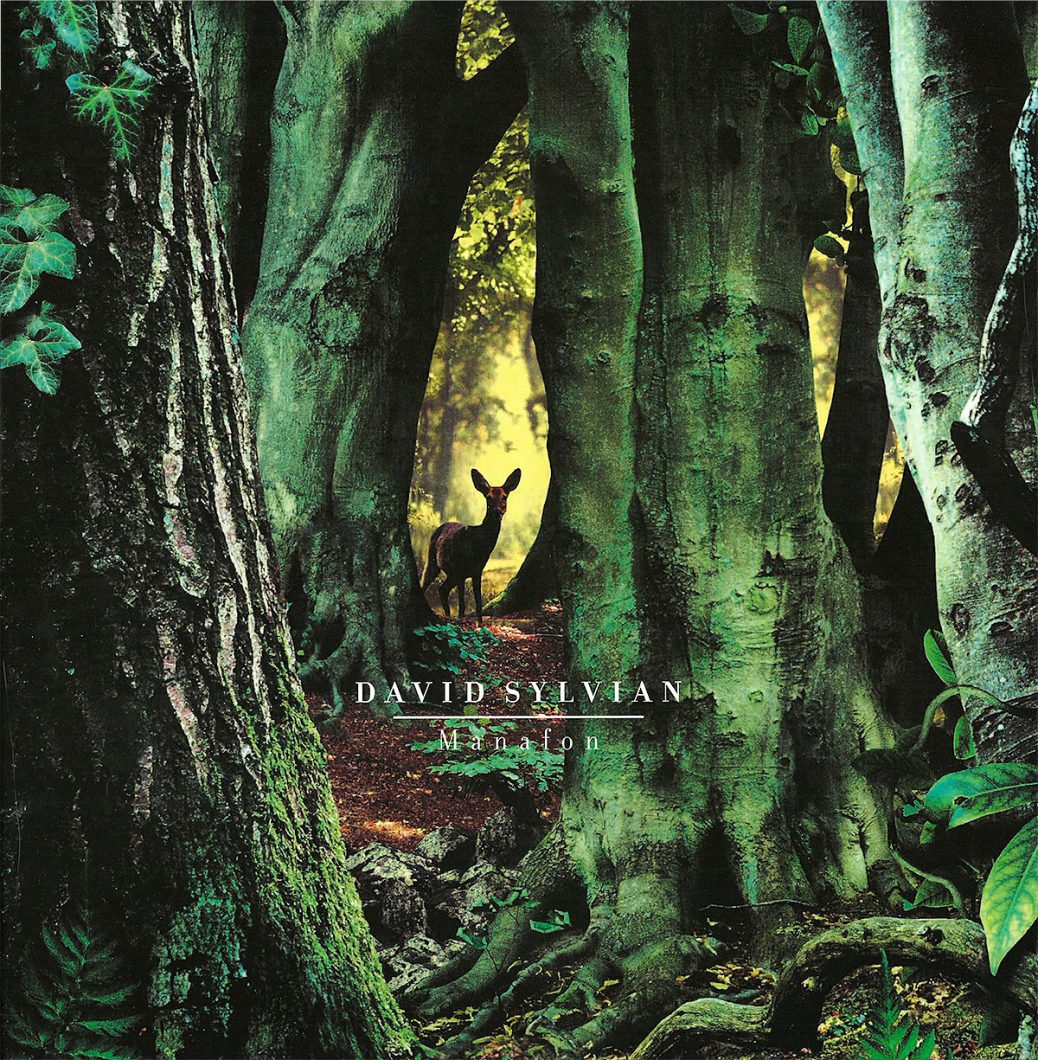

Al toen hij nog leadzanger was van de groep Japan (hitje: ‘Adolescent sex’) flirtte David Sylvian met culturen die ver af stonden van de heersende trends van die tijd: punk, new wave, disco. Hij vervlocht dat, aangevuld met de glamour van Roxy Music, in de prachtige pop van Japan, maar ondertussen tuurde hij de horizon af. Sylvian werkte samen met Ryuichi Sakamoto. Hij maakte, in 1984, een fenomenale soloplaat met Brilliant Trees. Een serie albums volgde, maar veel reuring veroorzaakten ze niet. En nu is er een cd die Manafon heet. Op track 1, ‘Small metal gods’, is dit het instrumentarium: gitaar, akoestische bas, cello, laptop, nog een gitaar, turntables (en een no-input mixer). Plus stem, die van David Sylvian. Het zou kunnen duiden op een song van een zanger met begeleiding. Maar de muziek is er niet, nauwelijks of minimaal. Sylvian’s stem is de hele cd naar voren gemixt – gelukkig zingt hij beter dan ooit. De begeleiding levert flarden, als verdwaalde wolken op een zomerdag. Des te verrassender wanneer die wolken hun intense schoonheid prijsgeven, zoals de turntablekunst van Otomo Yoshihide op ‘Random acts of senseless violence’. Herhaaldelijk lijken stem en wat er aan begeleiding is, los van elkaar van te staan. Sylvian laat zich niet van de wijs brengen door de opspetterende klanken. Ja, dat maakt van Manafon niet bepaald een alledaagse popplaat. Ja, hier hangt een ernstig label aan van minimal music en intellect. Kamermuziek, maar van de hoogste orde. De sfeer is die van de laatste herfstdag op aarde. ‘It’s the narrative that must go on, until the end of time’ zingt hij al in het openingsnummer. Geheel los van alle wanen van alle dagen. Een fascinerend meesterwerk, dat is het. Sylvian heeft er drie jaar aan gewerkt. Opnamen in Wenen, Tokyo en Londen. Met Nederlandse inbreng. De hoes toont twee werken van Ruud van Empel. Reëen tussen donkere bomen, maar met hoopvol licht aan de einder. Zoals de muziek.

mapsadaisical (30 september 2009)

David Sylvian, Manafon (Samadhisound); Polwechsel and John Tilbury, Field (Hat Hut)

by mapsadaisical

David Sylvian’s musical retreat into the forest is one of the most fascinating career paths. Like Scott Walker or Mark Hollis before, he has seemingly near-vanished from public view, producing works increasingly at odds with those from his past life as pop icon. These later releases are monumental slabs of one man’s artistic vision, wholly unaffected by such vulgar notions as the need to actually sell some bloody records.

The lush green artwork by Ruud Van Empel draws you into the foliage: Manafon is a continuation much further down the fork joined at Blemish. Sylvian’s lyrics, set with disarming clarity and confidence high up in the mix, make it clear just how far he has travelled – identifying with the reclusive, austere Welsh poet RS Thomas, locking his icons “in a zip-loc bag”, another recurring lyric dismissing his childish fripperies. The album’s musical floor initially appears sparser than Blemish, the combined weight of the credited contributors (including Christian Fennesz, Polwechsel, John Tilbury and Evan Parker) at times barely making a dent. Closer examination via headphones shows it to be teeming with life, from the seemingly incidental sounds (muffled voices, creaking and rumbling) which litter this clearing, crackle and glitch mulch at feet. The music’s relationship to the vocals is more oblique than in Blemish, Sylvian’s croon suspended upon restrained arrangements which have to find ways to weave through the gaps into sunlight- the violent burst of electric guitar in “125 Spheres”, the tendrils of strings in “The Greatest Living Englishman”, the snake of soprano saxophone in “Emily Dickinson”. Such is the level of detail that even the silences in “Random Acts of Senseless Violence” seem to howl. I’m so enjoying scouring this undergrowth that I don’t think I could find my way out, even if I wanted to.

Manafon transcends all trend, ranking somewhere in the spectrum between Hollis’s spare, wracked solo LP and Walker’s latter day art. I don’t mention many records in the same sentence as those, but Manafon is truly one of the finest records of this – or any – year. It even merits its own website – listen to samples there, and buy some bloody records from Samadhisound.

(Anyone – like me – fascinated by the musical language on Manafon is also strongly advised to pick up a copy of the new Polwechsel and John Tilbury album Field on Hat Hut, which is very fine indeed. Freed from the constraints imposed on Sylvian’s release, Polwechsel and Tilbury are able here to stretch out to make two long, patiently unfolding and impressively textured pieces of improvisation. Tilbury’s piano rings out into huge open spaces, where it is gradually encircled by strangely-treated percussion, John Butcher’s saxophone and a host of unrecognisable sounds in an ever-engrossing journey, rising to a furious insectoid buzz and rattle by the end. Frankly, it deserves a lot better than to be hidden away at the end of a review of another album, within vaguely-embarrassed parentheses)

Revolver magazine (Dutch magazine, september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Chris van Oostrom

(3 out of 5 stars)

Manafon zal zelfs de meest verstokte volgelingen van David Sylvian in twee kampen doen opsplitsen. Het is een werkstuk dat haast niet anders dan extreme reacties kan oproepen en zelfs de esoterische vruchten van ‘s mans samenwerkingen met o.a. Holger Czukay en Robert Fripp tot hapklare snacks reduceert. Op het volledig geïmproviseerde Manafon is het louter en alleen de stem die de melodie draagt, terwijl de bijdragen van de uit alle windrichtingen gerekruteerde musici (onder wie Otomo Yoshihide, Evan Parker en Keith Rowe) schuren, schemeren, strelen en detoneren. En vergeet vooral het alomtegenwoordige gekraak niet.

Wat moeten we hier precies mee? Uit de reacties die Sylvian reeds heeft mogen ontvangen, mogen we concluderen dat fantasie en associatievermogen overuren maken zodra de luisteraar geen houvast meer heeft aan vertrouwde muzikale referentiepunten. Ik beschouw het voorlopig als een boeiend experiment dat geen seconde langer had moeten duren.

Pitchfork (29 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Jess Harvell

rating: 7.4 out of 10

David Sylvian’s enjoyed a career common to art-rock-leaning, former English pop stars who’ve doggedly chased their personal obsessions in lieu of giving their old fanbase what they want, again and again. He’s not quite as intractable as, say, old peer Mark Hollis (Talk Talk). For one thing, Sylvian’s still releasing records. But from the time Japan ditched the crowd-pleasing glam sheen onward, Sylvian’s music has forced his cult to reexamine their ongoing relationship with the master’s music every few years.

That’s not to say each of Sylvian’s reinventions has been total, at least on an album-to-album basis. Manafon is of a piece with the music Sylvian has released in the 21st century, especially 2003’s small masterpiece, Blemish. Like that quiet, achingly personal record, Manafon reaffirms Sylvian’s aughts-forged connections with the modern avant-garde, be it jazz, electro-acoustic improvisation, post-glitch electronica, modern composition, or the artists who manage to occupy all four worlds while claiming none of them.

A small army of The Wire-friendly types contribute– sax colossus Evan Parker; Japanese “onkyo” ascetics Sachiko M. and Toshimaru Nakamura; guitar re-inventors on the level (and varying praxis) of Keith Rowe, Christian Fennesz, and members of Polwechsel; and many more. So this may be overstating the obvious, but pop music it ain’t. Even the unearthly minimalism of Japan’s “Ghosts” or Blemish’s “Late Night Shopping” are more immediate than anything on Manafon.

If the results aren’t as bracingly sour as Sylvian’s cross-purpose collaborations with Derek Bailey, they also lack the warmth he gleaned from Fennesz’s heat-prickly electronics. His collaborators’ small, brittle, seemingly disconnected instrumental gestures slip around the unctuousness of Sylvian’s infamously mannered high-romantic vocals. Sylvian’s remains a voice whose only peer for unrestrained melodrama is Antony Hegarty, and whose old-school voluptuousness makes Antony’s whinnying jazz-isms seem positively astringent. Sylvian’s voice doesn’t lend itself to the kind of modern scat one associates with “free” singing, nor does he even try.

But what drama this musical/vocal combination, oil and water on paper, creates on disc. Sylvian often sounds as if he’s reading verse rather than singing songs. Choruses are scant, or so languidly paced (as on “The Greatest Living Englishman”) that they barely register as such. He lets you know just how carefully he’s wrought his words, each line left to vibrate with portent before he’ll move onto onto the next. Never have the words “don’t know his right foot from his left” seemed so flush with private meaning.

At its best, it’s shiver-inducing, a sort of inverse of Joanna Newsom’s ecstatic prolixity, though with the same deliberate pacing that can alienate listeners used to songs that progress from verse to verse at the usual clip. Sylvian can rival Michael Gira when it comes to taking his own sweet time getting through a lyric. And at least Swans had brutal, repetitive rhythms to help guide listeners along. Sylvian makes no such concessions to rock tradition, however perverted. And it’s the music that makes Manafon a marvel, a mixture of free-improvisation’s moment-to-moment sonic epiphanies with Sylvian’s molasses-slow kinda-sorta torch songs.

Mark Hollis’ 1998 solo album is probably the closest comparison to the backing tracks of Manafon. On that underheard record, Hollis asked why couldn’t a singer-songwriter album move to the staggered (and staggering) quietude of Morton Feldman’s china-fragile chamber music. Sylvian takes it much further out, though. For one thing, while he knows restraint when necessary, you could never describe Sylvian’s performance as “hushed,” whereas Hollis often seemed to evaporate from his own compositions.

Sylvian is front-and-center on every song, which is good because he provides the only rhythmic and melodic stability, as the instrumentals dart and scratch and feedback around him, whether it’s the scouring burst of formless guitar noise that opens miniature “125 Spheres”, the random notes pricking the drone of “Snow White in Appalachia”, or the splinters of Bernard Herrmann-meets-AMM piano on “Random Acts of Senseless Violence”. Nothing makes “sense” by usual capital-s Songwriting standards; it’s music with the rhythm and textural illogic of precipitation. And no other singer is making music this bravely untethered to tradition. Though you know he’ll some day move on, you want Sylvian to explore this eerie, expectation-subverting world forever.

l’Unita (Italy, 18 september 2009)

Sylvian: ora canto il buio

by Diego Perugini

Di certo ci vuole un bel coraggio a pubblicare un disco come Manafon. Non perché sia brutto, tutt’altro, ma perché suona in netta antitesi con quanto ogg

i va dimodae in classifica. Tutto questo David Sylvian lo sa. E, sotto sotto, un po’ ci gode del suo status di artista schivo e alieno dai compromessi. Del resto la sua carriera ha sempre viaggiato all’insegna del cambiamento e della sperimentazione, anche quando sarebbe stato ben più comodo (e redditizio) dormire sugli allori e cavalcare, per esempio, la fama e il successo di Brilliant Trees, negli anni 80. E ora il fascinoso David se ne esce con un album scarno e impervio, una «musica da camera» tutta giocata sulla sua voce, magnetica e suadente, contrappuntata da pochi e mirati tocchi di strumenti. Niente singoli radiofonici, ritornelli orecchiabili e arrangiamenti pop, ma la voglia matta di rompere gli schemi precostituiti della forma-canzone, come già peraltro anticipato dal criptico Blemish, del 2003. «Per tanto tempo ho lavorato con le strutture tradizionali,maa un certo punto ho sentito il bisogno di qualcosa di nuovo e più immediato, che tagliasse i ponti col passato e mi lasciasse libero da ogni convenzione – spiega – Così, lentamente, ho sperimentato un altro modo di scrivere, che unisse improvvisazione e composizione. Le canzoni non hanno un vero sviluppo melodico: non si chiudono, restano aperte a tante suggestioni, fatto che ti regala un’enorme libertà anche dal punto di vista dei testi. Un processo iniziato in un momento difficile della mia vita e nato dalla necessità di scavare nei recessi più bui della mente e del cuore per trovare delle sicurezze».

Usa più volte l’aggettivo «astratto », David, per descrivere l’effetto straniante della sua ultima creatura, che si dispiega fra titoli di radicale intimismo come Small Metal Gods, The Greatest Living Englishman e Snow White in Appalachia, che certo non si prestano molto alle dinamiche di mp3 e iPod. «Non è quello il mio mondo. In questo disco la voce diventa come una presenza fisica nella stanza. Lo paragonerei, per certi versi, al teatro da camera: l’attore è al centro della scena, comunica qualcosa all’uditorio, ma altempostesso genera unsenso d’isolamento, mentre la scena è scarna, e le luci cambiano colore e intensità. Manafon funziona in maniera simile: è una questione di toni e di atmosfere, è un’esperienza diversa, da ascoltare in solitudine e nel mood giusto, non certo quando guidi in autostrada. L’ambizione è di incoraggiare alla riflessione, all’autoanalisi e alla pace interiore per poi proiettarsi più positivamente verso gli altri».

Già. Perché, se Sylvian può sembrare davvero «fuori dal mondo», in realtà non lo è affatto. «Vivere in America, dove risiedo ormai da molti anni, ti obbliga ad avere a una coscienza politica e sociale, soprattutto dopo aver vissuto l’amministrazione Bush, che cercava di mettere a tacereogni forma di dissenso. Il sistema politico Usa è così corrotto che è una specie di miracolo avere oggi Obama, un uomo a posto che sta cercando di fare la cosa giusta. I repubblicani lo stanno ostacolando in ogni modo, credo che abbia il compito più difficile mai capitato a un presidente americano».

INVIDIABILE INCERTEZZA Tornando alla musica, il futuro artistico di Sylvian è avvolto in un’aura d’invidiabile incertezza. Gli piacerebbe portare in tour il concept di Manafon, ma senza fretta. Prima ci sono le figlie da coccolare e un po’ di riposo nel suo eremo sull’east coast, immerso nella foresta, dove fare il punto della situazione. «Ho lavorato senza sosta da Blemish in poi e ora voglio fermarmi per riflettere. Ho davanti a me un’opzione, devo capire se è la strada giusta. Quando sei giovane non ci pensi, se ti piace una cosa la fai e basta. Adesso, però, ho una certa età e tanti dischi alle spalle: se devo impegnarmi in qualcosa, voglio esserne certo. È una sfida. E non so davvero dove mi porterà il mio desiderio di musica».

New York Times (27 september 2009)

David Sylvian

by Nate Chinen

Maturity comes on as a wrenching process in the songs that make up “Manafon” (Samadhisound), an artfully elusive new album by David Sylvian. “I’m dumping you, my childish things,” he sings in the opening track, “Small Metal Gods.” Later, on the ballad “Random Acts of Senseless Violence,” he issues this progress report: “I’ve put away my childish things/Abandoned my silence too.” It may be that Mr. Sylvian, the former front man of the new-wave band Japan, is denouncing his own glossy history. Here he’s on haunted-troubadour territory, as he was on his 2003 album “Blemish,” slowly enunciating his verses in a dark and confidential baritone. He places every kind of faith in the judgment of his musicians, experimentalists like the electronics artist Christian Fennesz, the turntable specialist Otomo Yoshihide and the saxophonist Evan Parker. Paired with his calmly despairing lyrics, their textures add up to a stark and ruthless tapestry. The songs themselves are wisps; the sentiments are heavy as lead.

Slant Magazine (23 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Jesse Cataldo

2.5 out of 5 stars

The best thing to call David Sylvian’s Manafon would be atmospheric. The worst would be empty. The truth lies somewhere in between, in hazily sketched semi-songs that drift along wispily, heavy on concept and light on everything else. Few albums have the gumption to attempt this kind of melodic slackness, full of material that hobbles around without any strong regard for how inapproachable it is. Scott Walker did it excellently on 2006’s The Drift, but that attempt was buttressed by creepy atmospherics and a firmly established sense of dread. In that case, a barren environment had time to grow on the listener because the footholds, as insubstantial as they may have been, provided a hook.

Manafon has a far slighter presence, which can be read either as the cause of its failure or an even braver venture into distant sonic territory. Either way, Sylvian seems to have a competent handle on what he’s doing, disassembling song structure until less than the bare basics remain. And a line like “The black sheep boy is leaving home,” from “The Greatest Living Englishman,” feels like a possible nod to Walker, a fellow avant-garde explorer.

It’s tempting to admire the album just for its sense of adventurousness, but the bare offering of Sylvian’s voice, reciting half-asleep poetic verses—sometimes with no instrumental backing, sometimes with a tuneless swipe at a guitar—is resolutely deadening. The effect of the silence here is less an infinite, mysterious a

ura than just silence, which is more interesting in theory than execution.

There are some amazingly atmospheric moments, like the murky saxophone passage on “The Department of Dead Letters,” which approaches with the steady assurance of a horror-movie slasher, dripping with eerie noise effects and askance string cues, like something bobbing through a swamp. It’s a fascinating interlude, one echoed by small moments that crop up here and there, from the surprising, garbly burst of noise that opens “125 Spheres” to the tinkling low-lit gloom of “Snow White in Appalachia.” But Manafon is far too preoccupied with unadorned stillness to be considered listenable. Its spaces of hollow inaction are far too big, and the concessions it expects of its audience far too large for so little payoff.

Dusted Magazine (15 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Jason Bivins

News of David Sylvian’s long-awaited new album revealed that he’d be collaborating not only with previous partner Fennesz, but with a bevy of top drawer improvisers from Vienna, London and Tokyo. Since 1984’s Brilliant Trees, Sylvian has sought out distinctive sounds and improvisers to realize his narcotic dreams, his melancholy, and his occasionally bleak, occasionally sentimental visions. In particular, his early collaborations with Can’s Holger Czukay and King Crimson’s Robert Fripp yielded an early fascination with psychedelic textures (even as he would use these to frame, say, a Kenny Wheeler solo). At times, the experimentalism that emerged from these early preoccupations is as prominent as songcraft in Sylvian’s world. His own smoky voice has remained the constant. Whether he’s flirted with love songs, with Carnatic music, or with “downtown” improvisations, that voice – somewhat stately in its articulation and disposition, but also weathered and a bit beaten – always shapes the music.

Manafon seems focused – both thematically and in terms of its effect – on detachment. You might say that this is due in part to the presence of his collaborators, and it’s true that the Tokyo musicians (sine wave specialist Sachiko M, turntablist/guitarist Otomo Yoshihide, guitarist Tetuzi Akiyama, and Toshimaru Nakamura on no-input mixing board) are often associated with such impressions. But while this cast of heavies is quite able to coax the various shades of grey from Sylvian’s increasingly spare songs, it’s Sylvian’s own vision that creates the detachment.

On several tracks, including “The Greatest Living Englishman” and the title tune, Sylvian refers distantly to a lone figure, who may or may not be Sylvian as he imagines himself, denounces himself, presents himself to the world. Elsewhere, he somewhat diffidently reels off multiple images or impressions of abjection, failure, indifference or loss. On “Manafon,” the line “And his wife she was a painter, but now she stains the altar black” suggest tragedies past. On the opening “Small Metal Gods” (with comparatively sumptuous contributions from Vienna’s Polwechsel), there’s a hint of menace when Sylvian sings “They’ve refused my prayers for the umpteenth time, so I’m evening up the score”. And on “The Rabbit Skinner” (where Fennesz and live signal processor Joel Ryan pair marvelously with saxophonist Evan Parker and cellist Marcio Mattos), Sylvian describes a setting where there is “No religion on beaches . . . [only] oil on gun-barrel and the hard taste of pennies.” His delivery is steadfastly melodic, often paired with a ripe sense of harmony and absolutely no pressure to respond mimetically to the sounds around him.

And these other contributions are perfectly calibrated for maximum effect. Many tracks place acoustic instruments in the foreground, with shifting backgrounds from electro-acoustic players. “Random Acts of Senseless Violence” features melancholy lyricism from John Tilbury’s piano, Keith Rowe’s prepared guitar wizardry, and the occasional slurp from Franz Hautzinger’s quartertone trumpet. Elsewhere, Otomo dials up some lovely slices of echo-drenched, crackle-enshrouded chamber music, only to have it sliced up by Tetuzi Akiyama’s slashing acoustic guitar. Sachiko M’s sine wave contributions could be a little more foregrounded (along with Nakamura’s), since they seem central to the tension, but they’re effective nonetheless. After a brief barrage of noise (“125 Spheres”), Polwechsel and Tilbury play gorgeously on “Snow White in Appalachia.”

There’s considerable emotion amid these improvisations. Parker plays some impassioned soprano at the end of “Emily Dickinson” (with lots of signal processing from Ryan and Sylvian). And it’s fascinating how some of the Tilbury’s piano harmonies (on “Emily Dickinson” and “The Department of Dead Letters”) bring to mind those from the intro to Sylvian’s “Forbidden Colours” and other early pieces. Maybe this is coincidence, or maybe Sylvian actually laid down specific harmonic parameters. But it’s quite something to note how consistent his musical preoccupations have been, even as he’s constantly transformed himself (or, perhaps, pared himself down).

In a mere 40-odd minutes, Manafon delivers a truly powerful vision. However central Sylvian’s bleak commentary, the weight and suggestiveness of this record gives it a sense of unpredictability, possibility, almost an openness beyond itself. It’s absolutely superb.

Bagatellen (21 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Paul Baran

Blemish must have marked a mini-seismic ‘event’ for David Sylvian when it was recorded over a six week hiatus, marking a departure from his normal precision in the studio. The songs were stark, aching confessionals that recalled the work of the late modernist Samuel Beckett in the honest nature of their ruminations on everything from family dissolution to the spiritually redeeming values of nature (”Fire in the Forest”). The signposts for a new agenda in songwriting on that record were already clear in the recruitment of the grand master of guitar improv, Derek Bailey, and laptop troublemaker Christian Fennesz. If a term called “art prospecting” could be invented, then the initial trickle of inspiration of Blemish would eventually turn into a gush of creativity for his new album, Manafon, which is bent on proving conclusively that former pop stars, with the right sincerity, can stretch out and experiment on the margins as well as anybody.

Perhaps paying lip service to improvised music’s internationalism by being recorded in London, Vienna, and Tokyo, Sylvian has broadened the panoramic reach that was initiated on Blemish, and recruited English electro-acoustic improvisers Evan Parker, AMM legends John Tilbury an

d Keith Rowe; bassist/cellist Marcio Mattos; as well as the Polwechsel unit of Burkhard Stangl, Werner Dafeldecker and Michael Moser, and Onkyo renegades Ottomo Yoshihide and Sachiko M. Each song on Manafon stands as deconstructionist ruin. Sylvian’s vocal acts both as a portal to the percolating electro-acoustic broadsides, as well as a fibrous tether that prevents these ‘songs’ from chaotic collapse. It’s a clever idea and it just about works, especially when he latches on to a distorted, melodic line by Fennesz (”Snow White in Appalachia”) or the rippling of neon-lit sine ticks by Sachiko M (”The Greatest Living Englishman”).

On this occasion, the pieces could be seen as new Twenty-First Century song cycle, with third person narratives providing a series of meta-fictional balladic portraiture. His pseudo-identification with marginal and lonely cultural figures are given voice, all united by extreme conditions of isolation in remote nature. Emily Dickinson and RS Thomas represent this in a literary sense, while “Random Acts of Senseless Violence” reminds one that such isolation can even have physically violent consequences for society. Paul Auster’s “Unabomber” character, Ben Sachs from Leviathan (who is based on Ted Kaczynski), seems to inspire the line “someone’s back kitchen stacked like a factory with improvised devices”.

Yet recent commentators have been mistaken about this recording’s rationale: Manafon is not an all-out improvisational album. Rowe, Fennesz, Yoshihide and co., are there to function as harmonic colourists. Sylvian would be the first to admit he is not Christof Kurzmann, or extended vocal specialist Ute Wassermann; he’s too considered and poised for that, and he places to a high value on the meaning of words. Instead this is an improvisational sound design album (a la David Toop) that attempts to marry the intuition of the human voice with the extension of electro-acoustic sounds. In this he succeeds, seeking to broaden the parameters of reductionist improvisation alongside a coterie of instrumentalists. Still, one might wish that there was more extended improvisational playing, on evidence of the Orwellian “Department of Dead Letters.” Summoning up cold corridors and musty state archives of the disposed, John Tilbury’s mesmeric piano modernism is nicely aided and abetted by Mattos’ shrieking cello exhortations. From being booed at the Glasgow Apollo venue, via ECM to Erstwhile his journey continues to be a fascinating narrative “until the end of time”.

AllMusic (14 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Thom Jurek

4.5 out of 5 stars

If there is a single theme that runs through David Sylvian’s Manafon, it’s simply: “No hope…no doubt.” Like 2003’s Blemish, it’s a rather difficult record, and its emotional and spiritual cousin. It’s dark, fraught with emotional and musical difficulty, nonlinear sounds and improvised music, and lyric themes that express a tension between hopelessness and the love of everyday life. The title comes from the name of a village in Wales where the poet R.S. Thomas once lived, studied the Welsh language, and published his first three volumes. He is the principal muse for Manafon, though there are others. Much of the writing reflects — like Blemish — Sylvian’s own struggles, though they are often (but not always) relegated to the third person. The studio musicians have either worked with Sylvian before or with one another: they include saxophonist Evan Parker, pianist John Tilbury, guitarists Christian Fennesz and Keith Rowe, members of Polwechsel, and turntablist/guitarist Otomo Yoshihide, among others. There are no drums. It must also be said that the presence of the late Derek Bailey (who worked on Blemish) is felt deeply on this recording, which was created on three continents. Despite these vanguard players, Manafon is not an avant jazz or “new music” record. It blurs all categories beautifully, and while it makes listeners work a bit, its payoff is a dark and luxuriant dream that cascades, floats, hovers, and changes both shape and shade often, and does so seamlessly.

Sylvian’s voice is front and center; it is so prominent that despite all of the instrumentation, in whatever musical conflagration chosen for a particular track, the voice is almost on its own. His phrases and lyrics were either improvised to fit the live sessions or were written in response to them. There are numerous electronic effects, but they never intrude on Sylvian’s voice, which is simultaneously emotionally engaged in the process and yet detached from the actual emotions expressed in the songs themselves — even when they are confessional in nature. The album opener, “Small Metal Gods,” is an example, and one of the most moving tracks on the set. Accompanied by acoustic guitar, laptop, electronics, bass, and cello, he sings “…You balance things like you wouldn’t believe, when you should just let things be/Yes you juggle things ’cause you can’t lose sight of the wretched story line/It’s the narrative that must go on, until the end of time/And you’re guilty of some self-neglect, and the mind unravels for days/I’ve told you once, yes a thousand times, I’m better off this way….” Other standouts include “Random Acts of Senseless Violence,” with stellar work by Yoshihide (who was instructed to use only the sounds of classical or modern chamber music), as well as Tilbury’s ghostly piano. Parker shines on “The Rabbit Skinner,” the lone instrumental “The Department of Dead Letters,” and “Emily Dickinson.” “Snow White in Appalachia” contains one of the most beautiful “melodies” on the set, and the closing title track is something so abstract yet memorable that it sums up both Sylvian’s lyrical and musical themes as a strangely beautiful construction of their own even if at times they are disturbing. Manafon is a quiet yet forceful stunner, a recording that, if heard, is literally unforgettable.

guardian.co.uk | The Observer (6 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

unknown author

3 out of 5 stars

Think Scott Walker punching a side of beef, and know that here’s another who’s wandered off the path of teen pop success to find a world that’s far more interesting (if far from easy listening).

yes…., that’s the complete review.

MusicOMH (14 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Peter Morrow

3 out of 5 stars

After the first, definitely the second, and most of the third through seventh listens it becomes increasingly obvious that sometime Japan lynchpin David Sylvian is not terribly happy. On Manafon Sylvian almost talks as much as sings about it over 50 testingly honest (honestly testing?) minutes. The sparing, affective strings-and-noise instrumental backing serves to highlight the emotion in the lyrics rather than carry any melody, all of which is built into his affected and oddly loungecore semi-spoken word vocal.

At its best – on Small Metal Gods, The Greatest Living Englishman and Manafon’s title track – Sylvian shares his introspective insights, delicately wrapped over a simple, balanced and carefully assembled soundscape. At its worst (much of the rest of it, unfortunately), it’s hard to avoid imagining a middle aged divorcee with a hangover crooning in the corner of a pub whilst a Fast Show parody of a DaDa cinema short gets more attention on the telly in the next room.

Whilst toes may struggle to tap, his arresting journeyman voice stands up well and holds attention over the full length of each emotionally strained line. But the lyrics have a habit of oscillating uncomfortably between an out-of-place man spilling his guts and a wannabe intellectual A-level poet, possibly because they were written more or less on the fly as the musicians laid down the bed.

The counterpoint between his smooth musings and the poignantly economical backing is quite striking, and respect should be paid to an ambitious production that includes some of the globes most noted improvisational artists. Amongst them are the pianist John Tilbury, Evan Parker and Keith Rowe, Christian Fennesz and some of his collaborators from the Viennese Polwechsel, and Sachiko M and Otomo Yoshihide in Tokyo.

Most of the sessions were recorded in very few takes and received little post-production; perhaps they would work more effectively in a live setting, albeit one with comfortable chairs, strong alcohol and clearly marked exits. It’s not that this is an intrinsically depressing album, but it is short on much to connect Sylvian’s world with that of anyone unfamiliar with his ways.

Fans of David Sylvian will doubtless appreciate the elegant compositions and Sylvian’s self-indulgent but soulful insights, but there is little to entertain the casual (or formal, or even bare ass naked) listener who may be better off back cataloguing Tom Waits and Nick Drake and realizing that they are not the same thing.