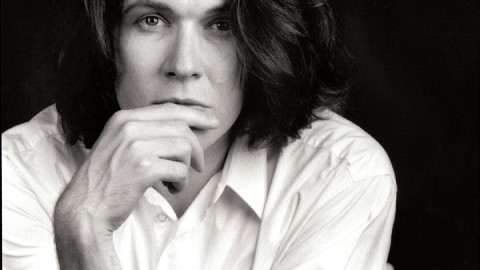

Four years in the making, and twelve years after his last solo album Secrets of the Beehive, David Sylvian offers us another opportunity to immerse ourselves in his unique aural landscape with his long-awaited new solo album, entitled Dead Bees on a Cake. The album offers us a sonic experience that is both familiar and refreshingly new.

A truly contemporary album, but one that is not guided by the current fashion of the day. A pop album by all standards, but one which stretches the envelope to its limits.

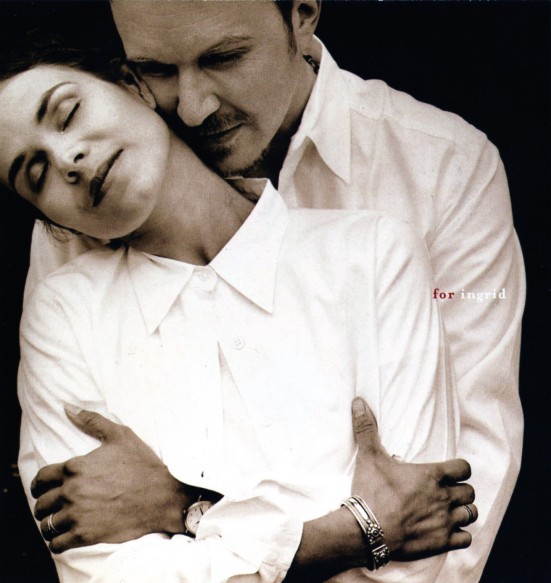

Dont be misled by the obvious reference to his previous solo album in the title, because many things have changed since those days back in 87. Not only did David exchange his worldly London existence for life in the relative backwaters of Napa Valley, United States. He now also shares his life with his wife Ingrid Chavez and family. On a professional level, David didnt sit still either. Highlights from his work between 87 and the present are the 93 and 94 collaborations with Robert Fripp, The First Day and Damage, his collaboration with former Japan members Steve Jansen, Richard Barbieri and Mick Karn on the self-titled album Rain Tree Crow, as well as several contributions to various albums by other artists like Hector Zazou, Andrea Chimenti, and Russell Mills.

A pivotal moment in time, when both his professional and private life crossed, remains the weeks prior to the recording sessions of Davids vocal contribution to Ryuichi Sakamotos UK/US single Heartbeat, the time he first met his future wife, Ingrid.

“The circumstances under which Ingrid and I came together are quite interesting. Ingrid was travelling through Europe on a press trip promoting her new release. [David refers here to Ingrids debut album May 19 1992 released on the Paisley Park label of Prince.] When asked by a journalist in Paris who she’d like to work with in the future my name came up. The journalist, an acquaintance of mine, told Ingrid he’d contact my office so that a meeting could be set up while she was in London. By the time she arrived there I had been called away to Paris on short notice to work with Zazou. Ingrid visited Richard Chadwick at the office leaving a letter and CD for me. On my return I found a two\ letters awaiting my attention. It was late afternoon. I was tired, numb, reeling from intense emotional stress which had been accumulating over the past 3 years. I picked up the first of two letters. It was from a girl whom I’d never met telling me a story of how she’d recently been visited by two beings late one evening one of whom she’d recognized as her deceased grandfather. The other was a Japanese gentleman she’d never seen before, whom she proceeded to describe, going by the name of Akira. Akira had a message for me. Despite my scepticism the message was wonderfully reassuring. Whether the story was true or false wasn’t an issue. Akira it turned out was Aki; Ryuichi’s manager who’d recently died in a car crash in Mexico. He’d relayed a message for Ryu in the same letter. I put the pages down on the table before me a little shaken by their contents. I then picked up the next letter, Ingrid’s letter.

Again I was very moved by its contents…and sadden that I’d missed Ingrid’s visit. I remember being overcome by the impact of receiving

both these messages at what could be referred to, in hindsight, as a critical moment in time for me…. I remember crying…. tears that accompanied an intense longing, an almost unbearable yearning for something only barely tangible.”

“I had already written ‘Heartbeat’ prior to leaving for Paris. I’d written a part for female voice, spoken word. I had no one in mind for the part. As I placed the CD Ingrid had left me into the machine bells sounded, lights flashed that even the virtually blind man I was had no difficulty seeing.”

“I later met Ingrid In Minneapolis. We travelled to New Orleans together for a few days. By the time we got to NY to record with Ryuichi there was little doubt in our minds that we were to be together.”

You then moved to the US, Minneapolis, and you have lived with Ingrid in the States ever since. What is your own perception regarding this change and the fact that you now live in a ‘foreign’ country? Are there any clear differences between the two countries and the overall attitude of its citizens? And has this changed your personal life in any way? Is there anything in particular from England that you really miss?

“On the one hand the move away from England was not easy, but it was quite desirable and necessary on the other. I felt like a man attempting to walk in molten tarmac. The pull that came with every step was tough. Arriving in the states I was keenly aware of how alien the culture was to me. American culture had interested me very little after my initial visits here in the late 70’s, early 80s’. It took me awhile to adjust. I don’t remember regretting the move I simply missed familiar aspects of European culture that I’d grown up with. Once I’d made the adjustment I settled into life here pretty easily. American life is not so difficult to navigate. There is less suppression of oneself and ones emotions here than in Britain where, it is true to say, we are a nation repressed in many respects. There is something endearing about this aspect of our character. Not wanting to bare all or burden others with our problems. It goes deeper of course, not exactly healthy. Turning a blind eye ensures that we don’t confront the real issues. Parts of the British make do attitude no doubt. But because there appears to be a greater need to deal with ones own personal baggage independently in Britain we often find creative means and outlets to do so. Still, it can be thoroughly frustrating to witness people becoming trapped by their own lives/minds/circumstances without the will, drive or know how to make radical changes. Mind you, it can be equally frustrating to constantly hear from those ‘victimized’ by life pouring out their psycho-babble at the drop of a hat. Here in America roots don’t appear to be so firmly entrenched. You pick up and move on with relative ease. A nation of exiles perpetually on the move, relocating. However, great emphasis is placed on cultural roots possibly as a result of people being so far removed from them. I don’t tend to find this necessarily healthy when it comes to creating fresh and exciting ideas although knowledge of ones past is often of great importance when developing a sense of self, for artists in particular. When there’s a cross-fertilization of ideas, backgrounds, and cultures something potentially new and innovative begins to take shape. Hybrids. There’s a tendency here towards segregation in all walks of life, the arts, throughout American culture in fact. A culture of convenience rather than one of confrontation challenges. Having said that there is willingness on the part of the American public to embrace and understand the new. There’s an optimism here rarely found and even more rarely embraced in Britain.”

“The changes I find in myself have something to do with location but far more to do with what’s going on internally, heart and mind. These tend to depend on relationships and time of life. I moved to Minneapolis in the hope of making major changes. I lived a very quiet existence there focused primarily on Ingrid and the growing family. I had next to nothing to do with the ‘industry’ outside of my work with Robert which allowed me the luxury of literally living an isolated existence from all that I knew before meeting Ingrid. I knew very few people in Minneapolis when I first arrived and I managed to keep it that way until I left. A very important period for me. Major events, major changes, the happiest of my life to date.”

Aside from the countries you’ve lived in there seem to be a couple of other countries you have a special relationship to. I’m referring here to Japan and Italy. Over the years both countries have had the privilege of repeated visits from you, most notably ‘The First Day’ tour in ’92 and the ‘Slow Fire’ tour of ’95. In addition, you’ve done a number of collaborations with residents from these respective countries. Ryuichi Sakamoto comes to mind here, and (less obvious) Nicola Alesini & Pier Luigi Andreoni, and Andrea Chimenti. Is this pure chance or is there indeed something to these countries and its inhabitants that may be the cause of this special relationship?

“I think the relationship I’ve developed with Japan over the years owes little to chance. Something drew me towards that part of the world early on. I was ignorant of what was at the root of my fascination but, as so often in my life, I felt a connection that was intuitively right. I followed that intuition on a journey that has lasted 20 years now. My relationship with Japan has changed dramatically over the years. Maturing as good friendships do. I don’t visit as often as I once did but I still feel the connection’s alive and well and is quite independent of the popularity or otherwise of my work over there.”

“Italy is another matter. It appears to have pursued me! I have made wonderful friends there as a result and enjoy the people enormously. However, culturally I don’t really indulge myself. I don’t drink alcohol, as a vegetarian I don’t relish the food, and if I can be honest I feel the burden of history weighs a little too heavily on the shoulders of that beautiful country. As a place to travel and explore it is magnificent but I could never spend more than a few weeks at a time in it’s embrace.”

On a very different level you also seem connected to Tibet. As a precursor to the ‘Slow Fire’ tour you performed a one-off gig in

celebration of the opening of the Peace University in Berlin, on which occasion the Dalai Lama was also invited. And sometime last year you nearly took part in a benefit concert to support the struggle for the freedom of Tibet (but unfortunately this concert was cancelled at the last minute). Can you tell us something about this involvement? And did you actually get a chance to meet the Dalai Lama in person?

“My interest in Buddhism brought me to the Tibetan teachings and his holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. I think it was in ’84 that I visited Nepal. It appears this experience lit something of a slow burning fire in me. It certainly stayed with me and was a source of comfort and inspiration for years to come. After living in Minneapolis for a few months Ingrid and I got involved with the Tibetan resettlement program there by sponsoring a family which opened the doors to that world a little. I’d never wanted to attend public charity functions or benefits as a performer in the past, and I still resist it, but the Tibet cause is deserving of efforts on every level. The personal connection made through our Tibetan friends gave the issues an even greater urgency as we’d hear details of the monstrosities of the Chinese occupation first hand and witness the very real affects on peoples

lives. I am so relieved that the plight of the Tibetans has reached the hearts and minds of young people around the world due to, among other

things, the high profile benefits concerts. It was shocking to find out how few adults had ever heard of Tibet a few years back never mind the occupation.”

“I’ve not been introduced to the Dalai Lama but have had the good fortune to have been in his presence on a number of occasions.”

You mentioned that you’re weary of situations where you’re put in the position of fulfilling public charity functions or benefits

as a performer. While following your solo career over the course of years I always had the feeling you tried to remain a-political as an artist. Both in the songs you wrote and in your presence as a public figure (unlike for instance Peter Gabriel and Sting who both are very active supporters of the struggle for human rights and/or the environment). I guess this also has to do with the contradiction between the concept of “pop star”, a label that was imposed on you during your Japan-days and which seems to stick on you until this very day, and the real ‘artist’ David Sylvian. Pop stars, more often than not, become mere icons in the eyes of the public and the act of standing up for specific, political issues increases this effect. As a result, the ‘icon’ can completely take over and mute the original and true message the artist tried to communicate with his audience. Am I right on this assumption or do other motives play a role in this as well?

“Yes, this is in keeping with my views on the matter. I have nothing against those who publicly stand up for one cause or another. I applaud positive action. In my case it appears inappropriate. I may be wrong but it seems to me that the fragile life of the work I create is better served by my ‘invisibility’, my silence, so as to increase the sense of intimacy between the listener and the spirit of the material.

There is a delicacy in the work. Its voice isn’t loud but still. Quiet. This makes it sound overly precious but that’s not the impression I wish to give. I’ve never been certain if its delicacy is my failing or my strength as an artist. Either way it’s out of my hands. To publicly stand up for one cause or another would, I feel, tip the balance and overwhelm the work. Untimely to make a change in one person is a political act in itself. Of all the arts music in particular carries this potential. It’s on this level, on the humblest of scales, that I attempt to make a contribution.”

Although the above is true for the early days of your solo career, things become less black and white when we consider your activities in more recent years. I already mentioned your performance at the opening of the Peace University in Berlin in 1995. Also, you donated an artwork that went up for auction at a benefit auction for the “War Child” project in 1996. And in 1997 you were about to perform at a benefit concert for the freedom of Tibet, were it not that the concert was cancelled by the organizers at the very last instance. Is this apparent change in attitude a deliberate change on your part?

“Donating the artwork to the ‘War Child’ exhibition doesn’t really signify a change in attitude although the concert for the Peace University might be construed as such. In that instance, to my mind at least, the writers, teachers, world leaders and artists weren’t representing a ’cause’ as such but the continuation of an important dialogue which encompassed the inauguration of the Peace University itself. The proposed concert for Tibet on the other hand was something I was simply incapable of refusing to do. As I said before I had some connections with the Tibetan community and truly felt their cause was under publicized and under funded. I had some reservations about getting involved of course but the evening was shaping up in quite an interesting fashion. Isham, Sakamoto, Czukay, Kronos. It had some real potential. But it fell apart due to fears on the part of the organizers that we’d fail to sell out the venue in question. At least that’s how it came back to me. This touches on another reason why it’s unessential that I get publicly involved in such projects. I am not a big enough name able to create the necessary attention such campaigns thrive on to make them worthwhile. Whether my name is added to the latest concert for Tibet or not makes no difference to the desired outcome of the event. I continue to prefer to make my contributions to such causes privately but I leave my options open.”

I can not help having the feeling that this change also reflects in your work. When we look at your collaboration album with Robert Fripp, ‘The First Day’, the whole feeling of this album seems to be more outward looking than your first three solo albums which are very much introspective, both in lyrical content and overall ambience.

“I guess I used my relationship with Robert to explore a different dimension in my writing. I was surfacing from what had been an enormously difficult time in my life and I needed to find the means of expressing myself in both music and lyrics when dealing with such heavy subject matter. ‘Firepower’ typifies the mood of the time quite well I think. I felt more comfortable at that time making oblique social observations or statements as a means of dealing indirectly with a mental state that was baffling not to say overwhelming for me. I believed and still believe in the underlying power and omniscience of divine love. The problem at that time was that despite my belief I had a hard time experiencing that love and could only approach it intellectually through the recollection of past experience. I attempted to express the anger, rage and impotence I felt at that time. The

blindness, the absolute darkness. I’d be better prepared to do that now having lived through it.

Nevertheless, the making of ‘The first day’, although difficult, proved somewhat cathartic. Not a successful work in my opinion for numerous reasons, but that Robert and I produced anything under the circumstances is somewhat remarkable. This doesn’t entirely justify the work I know but I do feel the live shows performed with Robert had something going for them. They couldn’t have taken place on the scale that we’d have wished without the existence of the CD itself.”

You mentioned that the album ‘The First Day’ wasn’t an entirely successful work but that the live performances with Robert

Fripp had something going for them. I presume you’re referring here to the performances preceding the album, also known as ‘The First Day’ tour held in ’92 in Japan and Italy (as opposed to ‘The Road to Graceland’ tour of ’93). This particular tour was unique, at least to your standards, as it was based on the concept of presenting entirely new material that was created in the two to three weeks of rehearsals preceding the tour. This concept also caused the material to remain in “a state of flux”, as you called it, during (a major part of) the tour. Yet, until then (or at least until the ‘In Praise of Shamans’ tour in ’88) you had shown great anxiety towards live performances. How did Robert convince you to participate? How did this concept work out, in your own perception? Did this experience, in fact, help you to overcome most of your anxiety towards performing live, since we have seen you perform live again only one year later, in ’93, and even in a solo performance during the ‘Slow Fire’ tour in ’95?

“Actually I was referring to both tours undertaken with Robert. Although the first was more of a challenge on a series of levels I felt the second came off with greater success.”

“Robert had stayed in touch since the Gone to Earth sessions. We’d spoken at that time of working together at some point in the future. Around the middle of ’91 Robert spoke of forming the latest incarnation of King Crimson. After a few conversations stretched over a period of months Robert asked if I’d like to come on board as vocalist for the new line up.

Although surprised and to some degree flattered I turned down the offer, as I couldn’t honestly take on the history of that band and work under Robert’s leadership. (Robert claims Crimson to be purely democratic but I’ve never felt that to be the case). There were other concerns: the need for independence having just surfaced from the RTC project, the instigation and pursuit of my own musical goals, Belew’s perfect chemistry with Robert as vocalist/guitarist, doubts concerning the compatibility of Robert and I on both a musical and personal level, (there’s a world of difference between a casual friendship and a working relationship, in this instance a possibly long term one), etc. Robert suggested we do something together anyway. Something on a smaller scale with less of a commitment to the future. I’d been offered a few live dates in Japan as part of a festival I believe, and Robert thought that this should be the first step in our collaboration together. Those initial dates fell through but we pursued the idea regardless setting up a new series of dates. Other than the session for ‘Heartbeat’ with Ryu I wasn’t actively pursuing any particular project of my own at that time so with an odd mixture of curiosity and ambivalence I went along for the ride.”

“The tour was slapped together with enormous speed. One week writing the material, another rehearsing it, ironing out all of the technical bugs (of which there were many. On the first week Robert turned up at my apartment with two racks filled with new equipment the majority of which he didn’t know how to use). Due to the time restrictions placed on writing the new material a fair amount of it was stretched beyond what I’d call it’s natural duration. I know the material would test my patience and level of interest on certain nights, as odd numbers would be drawn out indefinitely. Robert seemed to revel in the challenges inherent in this way of working. As this wasnt an entirely foreign method for him I felt the process presented greater challenges to me which is probably how Robert desired it. Initially I was excited by the challenges having never worked under these conditions but as time went on I felt the performances to be guilty of over indulgence and were as restrictive if not more so than the more traditional methods I’d been used to working with. This was due to the fact that we quickly fell into the trap of adhering to a relatively

rigid framework as far as each composition was concerned with the exception of the frippertronics based pieces, which did, due to the

nature of their construction, remain ‘in a state of flux ‘. This was due in part to Robert’s inability to commit to memory the basic structure

of the ‘songs’ and my inability as a vocalist to improvise more freely.

The songs being so fresh to us mistakes were frequent to the point that pieces were under threat of falling apart entirely on some nights. We never really got past the stage of rehearsal. Once the pieces are committed to memory it’s easier to open them up and explore them further without fearing their imminent dissolution! I could take certain pieces such as ‘The first day’ at my own pace night after night but that’s only a moderate freedom, a minor improvisation. Having said that I did learn a fair amount from the experience on a purely personal level.

Roberts continued presence in my life at that time was very welcome. I enjoyed his bright, insightful company. I also began to feel oddly at ease on stage for the first time in my life. But I felt the audience that was coming to see the shows based on my involvement expected more of me and I wished to give them a greater experience than I was capable of in this context.”

“As I indicated, I don’t feel it’s within my capabilities to improvise freely as a vocalist in the context of live performance. I do so in the process of composition and that’s where I find it the most valuable of tools. Composing is for me the most satisfying part of the whole process. Honing a piece to reveal it’s final form. My brother Steve and I are very similar in this respect. I think it’s fair to say that Steve doesn’t excel as an improvisatory drummer. Instead he composes wonderfully intricate, architectural structures on which the foundations of a piece stands. I use structure and melody and a bag full of other tricks. However, I would like to work with improvisation in performance with a group of musicians with whom I have a closer affinity. An instrumental outing could be interesting. Holger and I have touched on this a number of times. I can certainly see potential in following this avenue.”

“Throughout the projects with Robert it was he who tended to select the musicians. From the outset it was clear that Trey was to be an essential part of the line up. Trey is a wonderful musician but I felt that his involvement in every aspect of the work we did together helped to keep Robert in familiar territory (Trey was already working with Robert in approximately 3 different line-ups). When it came to recording the album, despite my suggestions to the contrary, we ended up with what was to be Roberts future Crimson line up minus Belew. (Trey, Marotta, Robert). This kept the sessions somewhat in the realm of Robert’s original desire for me to join Crimson. However, the sessions proved disastrous due mainly to my inability to work comfortably with Marotta (a fine musician) who tended to dominate them. Two weeks into the album and we didn’t have a drummer.”

“We made the best of things using drum loops supplied by the recording engineer David Bottrill. In fact one of the better pieces ‘God’s Monkey’ was created this way. Looking back I feel that although Robert was instigator of the project and influenced them to a greater extent than myself, for the most part we were something of a rudderless ship. My mental state during this period, as previously mentioned, was not conducive to producing focused work. Robert himself was undergoing trials and tribulations at the hands of the EG label. At some point Robert may’ve decided to use the collaboration as a safe context in which to bring his playing up to par for the projected Crimson reformation having been out of the loop for a number of years.”

“When it came to the tour we held auditions for a drummer. Pat was chosen out of three possible candidates. My contribution to the line-up was to invite Michael Brook on board. Although Robert, for reasons of his own, was unhappy about this development, it helped create a balance within the line-up, which was, for me, essential. I persuaded Robert to undergo the tortuous experience of 3 weeks of rehearsals. As a result I felt we were better prepared for the tour and reached greater heights in performance than on the earlier outing.”

“The live album ‘Damage’ was recorded in London towards the end of the tour. There are no overdubs. Although unhappy with both the mixing and re sequencing of the show (I intend to remix the album shortly) I think the recording shows the band working at its peak.”

Do you feel ‘The First Day’ tour was a natural progression of your previous working methods involving improvisation, which started back in ’86 with your collaborations with Holger Czukay and continued with the recording of ‘Rain Tree Crow’ together with Mick Karn, Steve Jansen, and Richard Barbieri?

“Was it a progression? I’m not certain. My interest in improvisation has never been to produce work of a purely improvised nature. It’s been a means of opening up the process of composition to allow for accidents, tangents, and new directions to take place and be pursued. The more accomplished the musicians the less interesting the process is for me. In such instances there’s a tendency to start jamming along familiar lines with all too much proficiency. With RTC, for all our skills, we are not a band that can, on any serious level, start improvising in a given genre of music because we are all relatively uneducated/untrained in that department. We aren’t rooted in any particular tradition and tend to be uninterested in pursuing traditional paths. The process is therefore of greater interest for me. Same applies to my work with Holger.”

With reference to ‘RTC’ you’ve often mentioned that you actively pursued this path of improvisation. You also have said that ‘RTC’ was an experiment, with musicians you knew and trusted, which you undertook to see if this was worth pursuing even further, with musicians less familiar. ‘The First Day’ tour can be considered as this next step. Do you still have the desire to go even further in improvisation?

Maybe even to go to the extreme of improvising live, in front of a (small) audience, in true Jazz vein?

“I’d like to find a group of musicians with which to continue the work which started with the ‘Steel Cathedrals’ soundtrack. I look upon the RTC project as a successful one. I’d originally conceived the project as a band with a revolving line up. It is still my intention to pursue that goal.”

“Although there are occasional inflections of jazz in my work I’m not attempting to create a form of ‘jazz music’. I’ve no interest in deepening my involvement with the jazz idiom per se. The musical proficiency found in jazz isn’t really what excites me as a writer. I can incorporate aspects of that into my work but it must be balanced with something that is less fluent that speaks in an everyday vocabulary and not a specialist one. I’ve always considered myself a pop musician and am much more interested in stretching the parameters of what the term pop music is willing to embrace than move into other genres. I also find the term ‘Pop music’ less defining and therefore less confining than any other category.”

A distinct feature of your previous solo albums has always been the synergy of the very diverse talents from fellow musicians. Guest musicians always get a prominent place in your works, yet it remains distinctly your album. Does this simply happen, as part of the chemistry between you and the other musicians, or can this be explained by the way you work in the studio? For example, video footage from, I think, the ‘Brilliant Trees’ sessions, as shown in the German VH-1 documentary, give a nice impression of the way you work in the studio. In that particular instance, you’re working very closely together with Ryuichi Sakamoto behind the piano to get a chord sequence just right. Is the physical presence of the guest musician with you in the studio an essential requirement to get an optimal performance?

“Not necessarily. If the musician is performing a part essential to the genesis of the composition or based on an earlier performance of mine then my proximity to them while working on the material may be of value. Each contribution has to be approached on it’s own terms. The temperament of the musician and the circumstances in which they perform at their best have to be considered. All of this tends to be worked out as you go along. The most important consideration is choosing the right person for the job in the first place. Not always an easy task.”

“I don’t have a vast array of methods for writing/recording. Anything goes basically.”

Can you tell us something about your approach to writing songs? Do you use a specific guideline, like working from a specific album concept or general idea? Do you require seclusion from your surroundings to concentrate yourself on your writing or do you actively seek new experiences/inspiration to fuel your creative process?

“Seclusion is important. Very important. I don’t tend to work from concepts although a broad notion of the playing field is often helpful. An enormous amount of thought, contemplation, meditation can take place prior to committing oneself to sitting down and doing the work but when that time comes you simply attempt to open yourself up and allow the unexpected to take place.”

Why have we seen so few remixes of your songs in the past? Only two tracks exist which were accompanied by clearly different

remixes, ‘Taking the Veil (Mendelsohn remix)’ and the two remixes of the ‘Darshan’ EP.

“I tend to believe that there is such a thing as a definitive version of a piece of music. At least that’s the measure I work to. As such it’s difficult for me to hand over the work to someone else to interpret in his or her own fashion. It’s like a director, Bergman for example, inviting another, Spielberg possibly, to re-edit his movie from scratch for him. The result may be good cinema but it’s no longer Bergman’s movie. I have made exceptions in the past where the possibilities of a piece are broad enough to allow further interpretation. The remix of ‘Veil’ was Virgins idea. I wasn’t happy with the results. The FSOL ‘reconstruction’ of Darshan is the only interpretation that has interested me to date.”

In previous interviews there are occasional references to the possibility of you doing a motion picture soundtrack. In fact, you’ve been asked to do a film score at various occasions, however the presented film scripts never appealed to you. Do you still have this ambition?

“I don’t really entertain the idea of writing a score for film. I don’t enjoy working to order as tends to be necessary when working in film. That is I don’t place much value on the work produced under such circumstances. (I refer only to my own work here. Ive enjoyed the work of others produced under these circumstances). To over state the obvious, I tend to work slowly which means there are many ideas, many projects which never make it past the ideas stage due mainly to time constraints. Rather than spend time working on what would be basically someone else’s project I prefer to focus my attention on my own work, as I’m likely to find it more rewarding. There could be possible exceptions to the above. If a director was to give me complete freedom in the work, if the themes inherent in the work were in keeping with my own concerns, or finally, if I was an admirer of the directors work (which would already indicate a connection of sorts).”

During your career, there have been other instances where you have come in to direct contact with the medium film/video. A number of promotional videos have been made over the years to accompany single releases from several of your albums. What was your involvement in the creation of these videos?

“It tends to be the case that when producing a video the overriding mood is often one of panic! It’s a last minute scramble brought about by Virgin’s indecision as to whether it’s worth shooting a video for a particular single or not. This has resulted in some poor quality videos as far as I’m concerned. I enjoyed working with Anton on ‘Red Guitar’. We attempted another for ‘Ink in the well’ but we didn’t pull it off second time around.

My favourite work to date has been done with director Nigel Grierson. He shot ‘Blackwater’ and my personal favourite ‘Orpheus’. The problem occurs for me when the imagery ties down to succinctly or powerfully the visual life of a piece of music. Our own mental images and associations are obviously so much more potent and broad ranging than a video could ever be that to have this hijacked by overwhelming video imagery is to diminish the (inner) life of the work to some degree. Having said that there are many songs that undoubtedly benefit from the addition of visuals.”

The film ‘Steel Cathedrals’ is probably the most important occasion where you were involved in film since you actually share the director’s credits together with Yasuyuki Yamaguchi. Can you tell us something about the way this film came about and the ideas behind the film?

“A Japanese video company asked me to produce a document of my stay in Tokyo surrounding the Polaroid exhibition that was currently on show there. After seeing some of Yamaguchi’s work I agreed to the project. I’d always loved the industrial landscape witnessed from car windows on journeys taken between Tokyo and Yokohama. Particularly at night. The buildings breathed.

These giant factories and plants that people devoted their lives to, put their faith in to satisfy their material needs. At least that’s the way it looked to me at the time and I wanted to reflect that in the work. In affect we made a film within a film. Preparations for a journey fulfilled the specifications stated by the commissioning company whilst Steel Cathedrals allowed Yamaguchi and I to explore subject matter of greater interest to us both.”

Most things you’ve done are very well documented, either by audio-visual recordings and/or in print. Yet, the scores you made to accompany the dance performances by Gaby Agis, ‘Kin’ from 1987 and ‘Don’t Trash My Altar, Don’t Alter My Trash’ from 1988, have always remained in relative obscurity. Can you tell as a bit more about these scores and the creative process that led to them?

“Gaby contacted me with regard to writing the music for what was to become ‘Kin’. I believe she’d already started rehearsals at that time. She didn’t give me any specific instructions except to leave the duration of each piece relatively open and not to make the work obviously rhythmically based. I wrote and recorded the work at home.

Each time a piece was completed I’d leave a copy with Gaby, catch up on the new developments in the work taking ideas with me back to the studio. Things fell into place relatively easily, only one of the pieces I produced we agreed was unsuitable otherwise there was an interesting exchange as the work developed over the weeks we had to put the piece together. I was particularly impressed by the degree of commitment the dancers exhibited.”

Another project that has remained in relative obscurity is the installation you created together with Robert Fripp in Japan in September 1994, which was called ‘Redemption’. Can you explain something about this installation to those who didn’t have the opportunity to see it like myself? What was the initial reason to do this installation?

What was the concept behind this installation? How did you and Robert approach this assignment? Is creating an installation any different from composing music or is the basic process very similar?

Large copper floor tiles are placed upon the central area of the exhibition space creating a golden rectangle upon which stand, at the far centre of the room, three charred, wooden chairs, lined up side by side, a foot or so between them. Beneath each chair sit three identical white enamel bowls

half filled with water. At the centre of each bowl floats a red lotus flower. Upon the seat of each chair is placed a model of a human skull cast in resin. Each skull has a small, neat hole carved into the centre of the cranium. A clamp is fixed to the back of each chair enabling a board to be suspended a few inches above the chairs height. On either side of each board is fixed a pigment transfer print by the British artist Adam Lowe.

The re-occurring images in these prints, abstract in nature, are the Himalayan Mountains. They are dimly lit from above casting a shadowy light onto the skulls below. Surrounding the chairs in neat, straight lines are 51 butter lamps placed upon the copper floor tiles.

The butter lamps give off a red/gold light, reflected in the tiles. Angled TV monitors are placed at intervals on the floor along the left and right sides of the space (5 per side) broadcasting the image of a human fetus in saturated red/gold colours.

At the rear of the space is a free standing, white enamel bathtub filled with mercury/mirror. Suspended directly above the bathtub (approx. 2 or 3 feet) is an oil lamp giving off a blue/white light, reflected in the surface of the mercury/mirror. Along the rear wall placed at intervals upon the floor are 4 TV monitors broadcasting the image of a full moon. This area is bathed in a gentle blue light in marked contrast to the rest of the space glowing in a red/gold.

Two medium sized monitors simultaneously broadcast Robert’s text in English. One large monitor broadcasts the same in Japanese. (Red on black). Two red lights dimly illuminate the space.

The primary composition ‘Approaching Silence’ is divided into two parts and is broadcast in the main room. The third part ‘Redemption’ is broadcast in the second room and comprises an edited version of Roberts reading of his text

“Basically Robert supplied the title for the work ‘Redemption’ and wrote the accompanying text. I created the music and visuals with input from British artist Adam Lowe.”

“As with other disciplines such as painting, photography, film etc. one area of work tends to feed and nourish another so ultimately there is an underlying connection or dialog present between bodies of work.”

You recorded your new album, Dead Bees on a Cake, in several places over the course of four years. Besides your home studio, you recorded in Ryuichi’s studio in NYC and, most notable (at least to me), the (wonderful) Real World studio of Peter Gabriel in Box. Can you tell us something about this process and the particular locations? Did you for instance pick out the Real World studio for any specific reason?

“I did a fair amount of pre-production at my home studio, Atma Sound, prior to starting work at Ryuichi’s studio located in the basement of his home in NY. We did around three weeks work together which weren’t as productive as either of us would’ve liked. Nevertheless we did capture some wonderful performances by Ryu most notably those on Rhodes piano. We worked on the string and brass arrangements at this time recording the sessions at Right Track studios. During the same week I recorded sessions with Marc Ribot (a very productive afternoon), Chris Minh Doky, and Scooter Warner among others. I returned to Minneapolis to edit down the material. With these initial sessions I hadn’t achieved what I’d set out to in many respects.

Ryu was to have co-produced the album with me but after three weeks it was obvious we weren’t seeing eye to eye on important issues so we called it quits and I undertook the production alone. I decided I needed to undertake a second set of sessions to enable me to create/recreate the basics for the majority of the tracks. As I intended to work in the UK and as I have a dislike of traditional recording environments, finding them sterile, geared mainly towards the needs of the engineer/producer, I settled on Real World Studios as in this respect it’s something of an exception to the rule. I’d visited the studios a number of times before. In fact drummer auditions for the Sylvian/Fripp tour were held there. I knew I’d feel at home in what is a very relaxed, creative environment complimented by quality technicians and members of staff that make up the community there. I’d originally planned a stint of two to three weeks but stayed on longer as I worked my way through a series of drummers, bass guitarists, and percussionists looking for suitable players. I finally settled on Jed Lynch and John Giblin for bass and drums respectively. Sessions were also recorded with Talvin Singh, Kenny Wheeler, and Deepak Ram. By the time I returned to Minneapolis I’d been recording the album for about two and a half months and much to my frustration many of the pieces still remained under developed. Much of the material I did have needed radical editing, re-sampling etc. I worked on the material extensively over the coming months trying to piece together what had eluded me during in the sessions.

Working with a computer-based system afforded me great flexibility when shifting information around. Detailed work was made possible to the degree that I was able to salvage the material without losing its original feel. I doubt I’d have been able to complete the album without this level of flexibility.”

“I recorded sessions in and around Minneapolis with local musicians (including Barbarella, Tibbetts) building up a library of samples that was to come in increasingly handy. I spent a couple of days in Seattle recording Bill Frisell. Ultimately the majority of work was completed at home although ‘home’ was different places at different times. Fortunately the studio my engineer, Dave Kent, had constructed for me was fairly mobile. I completed the vocals and final overdubs for the album in a small cabin located in the Napa hills minutes from Shree Maa’s ashram. I enjoyed working in isolation particularly where the vocals were concerned. I was able to immerse myself in each piece prior to recording the final takes which was necessary as it had been as long as five years in some instances since I’d originally written the pieces.

We mixed the album in Dave’s barn on the outskirts of Napa town.”

An unavoidable effect when you release your fourth solo album after an interval of 12 years is the inevitable comparison to your previous solo albums and there’s one clear difference to your previous solo albums I can’t resist asking you about. On first hearing, the album comes across as very eclectic, with a wide variety of instrumentation for the various tracks. Only after repeated listening the album starts to gel together. Was this a deliberate choice, a break with the previous albums, or did it happen by chance?

“There wasn’t a conscious decision made to make this collection of songs more eclectic than previous works. I remember similar comments being made regarding the Rain Tree Crow, Brilliant Trees and, to a lesser extent, Gone to Earth albums. It’s possible that ‘beehive’ is the exception in this instance. A body of work tends to surface over a relatively short space of time. Regardless of the degree of homogeneity in the overall style of the resulting material it tends to be united via its primary themes and concerns. This is certainly the case with ‘Dead bees When sequencing the album I did play upon the diverse nature of the material. The nature of the album shouldn’t be entirely clear to the first time listener until they reach its end. In this way I hoped to pre-empt certain preconceptions.”

This is your first, completely self-produced album. Did this give rise to additional hurdles or did you acquire enough experience over the years to take this job up yourself with some ease? In retrospect, would you do this again?

“I’ve been involved with the production of my own work for many years now.

As I’ve often elected to share the credit in the past I guess it’s difficult for people to gauge the extent of my involvement. I produced and engineered the Ember Glance ‘soundtrack’ at my home in London. By default I ended up producing the Rain Tree Crow sessions so I felt fairly comfortable flying solo on this album. I’ve enjoyed working closely with producer/engineers on the solo work as it frees me up at various stages in the game to focus entirely on being a performer myself. Also, it’s always good to have someone to bounce ideas off of.”

“I am some what reluctant to hand over the production reins now that I’ve seen this project through. But under certain circumstances I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of working with a producer once more. Whatever will do greater justice to the material is the road I’m likely to take.”

You have avoided the expensive recording studios whenever possible and have recorded a lot of the material from the comfort of your home studio. How is this different from recording in a professional studio? Does it pose other constraints on your work, like limitations of your equipment? Do you think this is a more general trend in music; individual artists who make recordings in their own basements and, possibly, even distribute their own music through the Internet without the intervention of a record company?

“The greatest luxury gained by recording out of ones own studio is TIME. Plus, as pointed out earlier, professional studios tend to be quite sterile environments as opposed to creative ones. There are exceptions (e.g. Real World) but in my experience they are far and few between. By consolidating Dave Kent and I had enough equipment to get the job done without making any major sacrifices. The desire to take control of ones own work from the outset, right the way through to distribution, is very attractive as the industry progressively narrows its field of vision.”

The artwork for both the singles and album are stunning as always. Can you tell us a bit more about how this came about? How did the collaboration with Shinya Fujiwara come about?

“Shinya and I have remained in touch since we collaborated on the Rain Tree Crow cover. Although primarily known as a photographer he is also one of the most respected critics in Japan, a novelist, a travel writer, an essayist, and an artist. While touring Japan in ’95 Shinya gave me a beautiful print of one of his drawings. It was at that time that I decided I’d like him to create something unique for the cover of my next album. I gave him the title of the album, a couple of rough mixes, plus some background on the inspiration behind the main themes. I had Anton take the photographs because a) it’d been some time since I’d been in front of a camera and therefore wanted to work with someone I knew well and b) I hadn’t worked with Anton for over 10 years and wanted to re-new the connection. Russell Mills designed the cover with Yuka and myself art directing the whole package.”

The B-side tracks on the single ‘I Surrender’ originally were part of a demo of sorts you and Ingrid made, called ‘Little Girls

with 99 Lives’. What made you decide to include these tracks on a commercial release? Are there still plans for a Sylvian/Chavez collaboration as originally reported on the Virgin America website or a possible solo album by Ingrid perhaps?

“We included the tracks from ‘Little girls..’ for two reasons. To satisfy the demand that had arisen as a result of the bootlegging of this material and to indicate possible directions in future collaborations. As we had no intention of pursuing these particular pieces any further we wanted to share them as they were. Ingrid and I are keen to start working on new material and will spend some part of this year writing and recording together.”

One project that was put on hold because of the new album is the ‘Best of…’ compilation. Now that ‘Dead Bees…’ is out, can you give us any indication when we can expect this compilation and what we can expect from it? Any chance this will be accompanied by a video compilation?

“There will be a compilation album although it’s a bit early in the day to give a clear indication of its contents. Suffice to say that I’ll attempt to give a comprehensive overview of the work I’ve created from ’83 to the present day. Ideally I’d like the work released in the early part of next year as we get underway on tour. There’s a possibility of a video compilation.”

It has been mentioned that ‘Godman’ will be the next single from the album and that it might get the remix treatment by some, still unidentified, artist. Can you tell us a bit more about this?

“It has yet to be confirmed but if there is a second single I’m fairly certain it will be Godman. Luke Vibert of ‘Wagon Christ’ has completed a remix. We’re currently speaking to other artists regarding further mixes.”