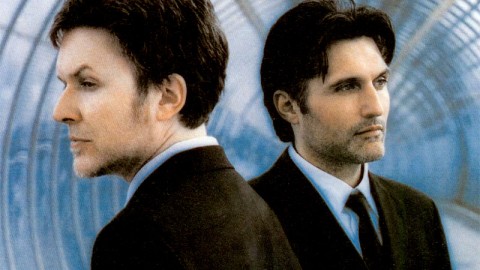

Since DAVID SYLVIAN split Japan at their zenith nearly a decade ago his fans have been praying they’d got back together. And now they have, under the name of RAIN TREE CROW. STEVE SUTHERLAND meets Sylvian to discover the impetus behind the band’s re-emergence.

David and I are laughing at death, the way two young men should. More specifically, we’re laughing because two hours of casual philosophising and amateur psychiatrics have allowed us to share one awesome cosmic joke.

The joke goes like this: David says he’s presently suffering from intense emotional trauma. David mentions this completely unselfconsciously, the way you or I would mention we bought a new shirt or watched a show on TV. David says the last time he suffered such intense emotional trauma, he was forced to split Japan, his deeply stylish group who, after years of pioneering their unique design of Charles Rennie Mackintosh melancholic romance-in-aspic, had finally made it big. Ironically, this latest emotional upheaval has brought David back together with the rudiments of Japan – swoony bassist Mick Karn, keyboardist Richard Barbieri and David’s drummer brother Steve Jansen – to work on an improvisational project which thrives by the name of Rain Tree Crow. For almost a decade David has been releasing his by-turns ambient and jazzy collaborations with the likes of Danny Thompson, Holger Czukay and Robert Fripp under his own name, but just now he says he doesn’t feel sure enough of himself to undergo the tortured self-examination necessary to create a record personal enough to bear his own name.

“For the almost three or four years, I’ve being going through quite a powerful emotional change in my life and it took me a long time to come to terms with what was happening. So I thought, rather than just slogging away without getting to grips with it, I should perhaps collaborate and allow myself to work more on the spur of the moment. The idea was to have a loose outfit of musicians and just respond to the characters involved which was actually fun.

“I’ve been going through quite a negative time, intense… a lot of things came up about my past which I found very difficult to deal with. So I went into analysis for a while and I found it really interesting to get to grips analytically with what was going on, especially as it was totally against my nature. My primary instincts are spiritual but I think it’s a mistake to jump straight into that area because spiritual awareness is such a neblous thing that if the mind is discoloured by experiences in this life, it’s so powerful it can conjure up anything you think you need to believe in. It’s quite dangerous in that respect.

“So going into analysis was a kind of clearing out process and it helped me to understand myself a tremendous amount. It’s ongoing, it never ends. It’s never, ‘Well, I’ve done it now, I understand’. The more you know, the more there is to know.

“I found my childhood was all about desensitising myself to deal with my environment because if I soaked in all the experiences and they really I touched me that deeply and they hurt me or whatever … I mean, you often hear parents talking about hardening up their children a little bit, otherwise they’re not going to be able to exist in this life? You’re immediately taught to put up barriers to the soul so these things don’t get through to you and think, maybe the majority of one’s waking life is spent on automatic, just going through situations without that pause which allows the consciousness to come in and question, Why am I doing that? Am I doing the right thing? What would I say if I hold back for just one second? Will something else come through which will be far more relevant than me just showing my intelligence or humour to another person because I want that person to like me? We’re conditioned for self-protection with all these games we play.”

Out of nowhere it struck me that the pause for consciousness to arrive is what the artist strives to introduce into everybody else’s life. You and I might spend all day grubbing around to survive and then we might watch a film, read a book, listen to a record, look at a painting and, if that in any way affects us, it’s surely a step outside the merely pragmatic.

“Thats exacatly what I feel,” says David. “The function of art in society is to create space where consciousness can be reached and you find, within that space, the room to ask questions. Questioning is the road to self-awareness and art can define the parameters within which that question may be asked – the quality of that question, lets say. To me, art in society is humanitys way of sensitising itself. Its a sensitising process. Its ongoing.”

We talk about how adding the analytical aspect to the writer’s armoury neither destroys the joy of the accidental nor hampers the creative process but, on the contrary, adds another, objective dimension. We talk about how all his work is a work in progress but how he won’t use the old cliche of every piece being just a snapshot of the time to be left and moved on as a convenient excuse for failure.

“The failure is to not communicate what you’re trying to communicate,” says David. ‘One has to acknowledge that. One has to keep working on a piece until it mirrors the inner emotions that brought it into play. Some people think I should maybe take my work a few stages further but I have trouble with that. I find it very difficult to put one note in a composition if it’s not relevant for that note to be there. To me, that’s a bit like putting soft focus on a lens just to make sure you get a decent portrait out of it. It’s not necessary. Even if it’s a little more difficult for people to get into or even if it’s not as entertaining as maybe people feel it could have been, I still feel it’s more honest to keep it in its raw state as much as possible.”

When David arrived, I didn’t recognise him. He was wearing a big tan dufflecoat on a warm spring day and his hair was long and brown and parted in the middle. I think he was slightly hung-over because he’d been drinking the night before, helping to edit the first Rain Tree Crow video.

While we were unwittingly heading for the punchline he joked that my lunch was his breakfast and I joked that people will say he was famous, then he went away and pissed about for a few years, and now he’s come back again.

This wasn’t news to David: “Most of the people who write about me in that context, it’s like they see a swimmer dive into the water and they don’t follow him underwater, they just notice when he comes up for air. Thats the problem with me, they just notice when I come up for air every now and again, whereas the important work’s going on underneath. All the work that I’ve done in the past eight years is what I’m about realIy and everything I did with Japan prior to that was making massive mistkes and learning about why I make music. I was doing it for all the wrong reasons. I got to a point where I was trying to write about myself but found I couldn’t within that framework and finally I found I had to put that aside to find myself musically and psychologically.”

He has to admit, though, that Rain Tree Crow is his most easily accessible work since Japan.

“I was aware of not putting too much emphasis on the lyrics because it was a group project and the focus shouldn’t be on the singer but, even in trying to simplify the lyrics, certain images crept in that were pertinent to the emotional struggle I was going through.

“I mean, the image of crow is a symbol that became more and more relevant. I developed this fascination with crows a while back. I somehow felt a sense of being related to this image of the crow whenever I would see them. l bought some crow artpieces, I bought some books about them and, although I hadn’t worked out why that was, over a period of time, I came to realise that it was this dark emotional experience I was going through personified. In some oblique way, it enabled me to objectify this experience onto this symbolic bird, and then deal with it.

‘I’m still going through that. I’m still dealing with it. I’m still writing material where the imagery is crow-based. Haha! Its becoming more and more fascinating. I came across Ted Hughes “Crow and it was very close to what I was dealing with and I found that interesting. And then there was what the crow symbolises generally – the blackness of the crow has been related in history and different cultures as like the light out of chaos, light out of darkness… it’s that state before the light comes through which is quite in keeping with my negative state of mind waiting to be alleviated.

“Somehow there’s all this historical relevance which I had no idea of before actually dealing with this symbol. It’s having all these fascinating, exciting resonances.”

When I first heard the name Rain Tree Crow, it sounded Red Indian to me, and David doesn’t deny this although he says it wasn’t conscious. Only afterwards did he realise that all the music on the forthcoming album was only acceptable to him if it corresponded to a desertscape he was imagining. Such sense of place has always been important to him. When he was younger in Japan, his songs were travelogues and he seemed forever on the move through continent after continent, in search of inspiration, maybe in a bid to escape or discover himself. He now knows it’s all the same thing. “There’s this sense of place which is an ongoing thing for me, a sense of yearning that’s always there in my work. It’s actually a place I don’t expect to find because it’s not exactly a physical place I’m talking about. I want to find somewhere where I can feel that, by being there, it has a certain effect on me that will compliment who I am.” Realising that travel was just a physical symptom of some inner restlessness, David hasn’t actually been anywhere since Christmas 1989 when he visited Turkey to see the Whirling Dervishes and wound up most affected by the smog in Istanbul. Still, he talks wonderingly about a friend’s brother who went to Brazil and met an obscure religious cult in the jungle who gave him these drugs which made him vomit and then got him smashed for six days solid. During this time he partook of a religous ceremony wherein other members of the congregtion were by turns kindly and aggressive towards him and, although it freaked him out at the time, the guy now reckons it was without a doubt the most intense experience he ever had.

As David tells me this I can tell he wishes he’d been the guy.

“I throw myself into situations just to act,” he says. “The experience is the journey, not the arriving because, in the psychological and spiritual sense, there is no arriving. It’s a constant process of understanding.”

So what exactly was this emotional upset, a by-product of which is the gorgeous Rain Tree Crow? Spiritual malaise? A broken romance? A confidence betrayed?

“It hasn’t been easy to put a finger on, says David. “We’re always building up an image of ourselves with which to deal with the world around us and my image just began to fall away. I found I couldn’t actually relate to my self-image. Whatever was going on internally was distancing me from that sense of self.”

While many popular musicians take the opportunity afforded them to change their persona, David Sylvian is taking the much more honest, perplexing course of using his talent to discover his personality.

“Thats my responsibility but, as creative people, were not just dealing with our personal histories, we are dealing with the spiritual side of ourselves which l believe is connected with a collective unconscious. We get information through this source, through our spiritual source, and it can be beyond our knowledge of ourselves as a race. Something can be put into a piece of work which is beyond humanity and we can recognise within that artwork something of our greater selves.

“Its like standing next to a massive ocean and feeling this sense of openness and yearning and joy and all the rest of it. You’re connecting with something and, although you don’t know what you’re connecting with, you know its of primary importance somewhere within your being and you somehow feel that isn’t unique to you. Everybody can experience this and art is related to that. Ideally art sould go beyond the personal.

“I think what happens is this creative energy comes through the artist like a medium and the artist clothes it with his own neuroses or interests or obsessions and puts it out to the world. So the artist takes this initial, lefts call it inspiration, and clothes it in as pure a form as possible so that it will reach a large number of people. A masterwork is created by an artist who has somehow managed to bring that experience through him and out into the world with as little of his own problems or obsessions clothing it as possible.”

I ask David about his goal. Was it to reach a point of wisdom or was the quest simply there for the sake of the quest because… well, its there and has to be dealt with?

“Well, if you don’t deal with the question, Why are we here?’, or, What is a human being?’ everything else seems superfluous. Now you could say, Well, everything is superfluous so there’s no need to dwell on it. Lets just go out and live life and don’t worry about these things’. But thats not my nature. I tend to dwell on it. The goal, I would say, is complete consciousness and it’s to do with the here and now. I don’t believe consciousness is something that comes in time or after life or after death or whatever. If you can’t have it here and now, it isn’t real anyway. So you have to make contact now. It’s to do with being in time, not projecting out of it.

“We’re very rarely in the moment. Sitting here, our minds are constantly flitting around, playing with time in different ways – the past, whats hapening next and so on.”

So Davids goal is the utter appreciation of now.

“Yes, and by doing that there are rewards. You make contact with certain sides of yourself which are rewarding, which open up doors. You become a far more flexible person if you’re not protecting yourself all the time.”

Here comes the joke. Now is all we’ve got. If we run around living it up or stop to savour and make contact with our consciousness or waste away contemplating our navels or whatever, we’re still staving off the inevitable – death, the great unimaginable.

I tell David my notion of wisdom is probably accepting death without fear, coming to peace with one’s mortality.

“If you recognise that as something of primary importance to your development, that’s very true for you. I’m of a different nature,” says David. “Ive always thought the idea of nothing after this life is a fantastic release, a fantastic escape. I don’t have any desire to go on living or to sustain my consciousness beyond this lifespan. If there was something else it would seem like a fantastic cop-out to me and far too easy. I can accept that, don’t have a fear of that.

“I’m dealing with the same thing but frorn another approach. My fear is the opposite. My fear is of life. My weakness is the will to go on. Why am I here? Why should I go on? And the more I learn, the more I understand, the more I fall in love with this experience.

If he carries on like this, I tell him, if he acually manages to embrace every moment, if his journey is so successful, so rewarding and enriching the he rejoices in being alive, he might someday come to catch my disease and fear death. And then where would he be? Hed have to start all over again from the other side of the darkeness. All that work in vain. What a f***ing mighty joke!

So David and I are laughing at death. In a moment we will order tea.

(interview appeared in Melody Maker, March 30 1991)