This brilliant carreer by Steve Sutherland

This interview with David Sylvian is taken from the Melody Maker and was first printed in the UK on 12th May 1984

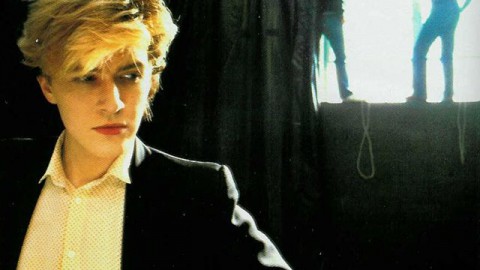

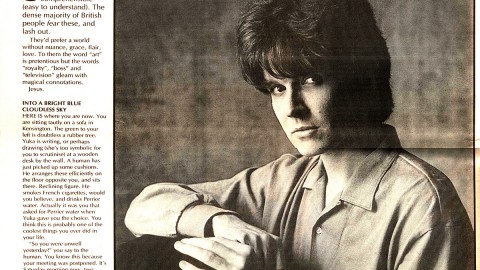

Once described as “the most beautiful man in pop”, DAVID SYLVIAN steps out of the shadows this week with the release of a new single, “Red Guitar”. In his first major interview since Japan split, he talks to Steve Sutherland about Picasso, paranoia, the art of improvisation and his forthcoming album, “Brilliant Trees”.

Offered the choice he sat by the window, haloed in light, warmed by the sun. I sat in shadow. Strange, I thought, that we should be this way round.

At last. I’ve wanted to talk to you for ages.

“Yes, I know. I just hope I don’t disappoint you.”

Oh, but then he sipped ice-cold milk, smoked French cigarettes and wore shades; David Sylvian’s emergence is suitably gradual as befits a contented recluse.

I’ve been chasing him for nigh-on two years, religiously ringing Virgin every fortnight to be told “David’s here, David’s there, we don’t know where David is”, or “David doesn’t feel he’s got anything to talk about at the moment” so often it has become something of a standing joke.

Since Japan split, he scarcely broke cover. There was a snippet in The Sunday Times Magazine significantly out of sequence with his cautious manoeuvres, a retrospectively tilted interrogation in Blitz with a photograph to substantiate the rumour that he was hiding himself in a stubbly beard – barely anything else.

And then suddenly there’s a new single, a new album and then this tte–tte at the Portobello Hotel. He’s clean-shaven again and I’m bristling with theories so you’ll forgive me if I begin with a grand contradiction, a preconception I’ve faithfully nurtured concerning the mightly impulses that coax David Sylvian’s tiny responses. Like one of those natives fighting shy of the camera for fear that a photo will diminish his soul, David Sylvian appears petrified of emotion; creating art, building structures, seeking discipline, doing anything to avoid revealing himself.

He listens attentively, smiles and nods his approval.

And yet there’s a horror there too, an unspoken suspicion that the precious self must be sought and extinguished to make manifest any truth. And what if, when all the external influences and irritations are peeled away, that essential self turns out to be nothing but a void acted on by its environment, an “Apocalypse Now” of the soul, guilty of any mad misdemeanour in the right or wrong circumstances? Does that make sense?

“Yes, it does, it does! It’s a good observation. It’s something I wasn’t consciously aware of, something that I must have pushed to the back of my mind. You have to hope that it’s not true, otherwise it makes everything you’re doing totally invalid.”

Japan were doubt disguised as confidence, a beautiful symmetry frail as an eggshell. They are no more, but I suspect David Sylvian is still working because he wants to convince himself there’s a point to life. Everything must be important.

He acquiesces again: “Uh huh. You’re one of the first people I’ve spoken to about the new album so your questions are making me think about the songs a little more than I would do. I’m too close to think about them really so anything I say now will probably be a very shallow interpretation of what the songs are about. That’s not to say they’re invalid, just close.”

David Sylvian’s new album is called “Brilliant Trees” (out sometime in June) and features an inspirational array of talent including the eccentric German Holger Czukay, jazz trumpeter John Hassell, David’s brother Steve Jansen and Richard Barbieri from Japan, and a core of New York funk supremos.

It’s Narziss to John Martyn’s Goldmund, the monastic rather than the raging route to “Solid Air”. It bears the influence of Tao Te Ching Lao Tzu and John Paul Sartre’s “Nausea”. It could have been a Nick Drake album had he lived. It harbours respect for Robert Wyatt, Joni Mitchell and Brian Eno and it bears no relation to any place, any time except the contemplations of David Sylvian’s soul. It’s title track asks: “Is this grip on life still my own/When every step I take leads me so far away/And every thought should bring me closer home?”

“I’m out of touch with everything that’s going on. I just pick things up from listening to all different areas of music from all different times so my influences can’t be pinpointed as easily as perhaps you used to be able to.”

“Brilliant Trees” was recorded in Berlin and London.

“I wanted it to be based in Europe because I wanted everybody to be in a strange place, including myself, so that we were all foreigners working in a studio with a feeling of adventure in a way you know, everybody coming to a spot to do something. It’s the first time I’ve felt like that recording an album.

“With Japan I normally had a loose structure to work with but this was very loose. Musically, there was no major concept, all I had in mind was that the musicians would come in and really perform as they felt. I wanted to create a relaxed environment for them to work in so they felt totally at ease to do whatever they liked on the tracks. The whole concept of the album was really to get performances from the people I was using, whereas, with Japan, it was never a performance, it was normally an arrangement, a composition.

“On this album the compositions are very simple and the idea was to let people work with a very loose framework and improvise over it.”

It must have been fascinating, not to say nerve-wracking, to discover how others interpreted his basic ideas?

“Yeah. I was familiar with the work of most of the musicians who played in the album so, in a way, I knew what to expect and none of them let me down. Nobody disappointed me at all, everybody was as true to form as I thought they would be.

“The idea of improvisation was very important because I no longer felt I had to prove myself as a songwriter. I actually didn’t feel like sitting down at home and writing songs anymore. I felt like I’d done that before with Japan and there was no point in keeping on doing it so I went into the studio with virtually nothing, totally unrehearsed. That was the excitement of it all, to get more emotion out of a piece of music than I ever did before.

“With Japan I’d take a very long time about recording vocals and I’d iron out all the little idiosyncrasies in the voice that I didn’t like but this time I didn’t. Maybe that’s a sign of courage, maybe it shows a self-confidence I didn’t have before?” I’ll offer no retrospective on the latter-day Japan’s place in the scheme of things. They existed, that’s all, and any contemporary appeal was purely coincidental. They offered no reasons for “Tin Drum”, just a few influences. They offered no excuses for the live requiem “Oil On Canvas”. It just came out. Their self-obsession alone was cause for fascination, especially Sylvian’s approach to language, which was always carefully, almost obsessively, oblique.

But where, say, “Tin Drum” was content to shelter behind a concept, luxuriating in visions of China, “Brilliant Trees” seems much more graphic, much less prone to employing imagery intent on obscuring as much as revealing its meanings. Sylvian traces the improvement to “Forbidden Colours”, the soundtrack he wrote for “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” with YMO’s Ryuichi Sakamoto.

“With ‘Forbidden Colours’ I achieved something I’d never achieved before in writing a lyric about myself which had no answer. It had a question about religion. I’ve got this thing with religions in general. I’m interested in people’s philosophies and why they cling to them. Do they need something to rely upon because they’re not strong enough in their own life or are they clinging to them because there’s a real value in it that I miss?

“At that time, I was becoming more obsessed about Christian religion and ‘Forbidden Colours’ was the first time I’d achieved that kind of writing, putting something into lyrics that was just an expression of what I was going through, that had no ending. It still hasn’t got an end to it and the music wasn’t coloured in any way. It was very honest and that’s what made me decide to carry on writing. I couldn’t go back. I was just incapable of getting out so I just wrote directly about myself.”

Sylvian’s writing with Japan was reflective rather than happening, if not the romantic poetic ideal of emotion recollected in tranquillity, then at least emotion tempered by thought. His songs were more like frigid sittings than teeming situations. His neurosis was unique. He was passive and tranquil where pop revelled in wild exaggeration.

“Yes I tended to write on reflection, after going through something rather than writing about a certain thing when I was going through it because I used to think you couldn’t get the best viewpoint like that. I would always try to make it maybe a little less personal-sounding so that people could relate to it more…”

He checks himself and discovers some doubt: “…or… maybe I would disguise it, I’m not sure. Maybe I was too afraid to show it that openly or maybe I was not capable of showing it that openly. On this album, I think I’ve been more direct. Even though I didn’t perform that much on it, I feel I’ve created something musically and lyrically in a far more personal style than I ever did before. I’ve written about some things when I’m in the middle of experiencing something – not having a solution or even a clear observation of it.

“This album has more of a confused feel about it you know there’s always a period in your life when you’re totally sure about yourself and suddenly something happens and it breaks down your whole picture of yourself? Well that’s what happened to me after Japan split up and now I’m writing as a confused person whose constantly doing things and acting in certain ways that surprise him, rather than as a person trying to keep control of himself. I think the writing’s more valuable for that.

“People used to say ‘you’re music’s so personal, aren’t you embarrassed if you’re in a room when people are listening to it?’ And I always used to say no because it was more an observation and I didn’t think people really related to it as just my experience, people related it to themselves. Well it’s a little more difficult for me to sit with other people in a room when this album’s being played, because a couple of songs are very personal statements about personal things that I’m probably still going through.” The best Japan songs – “Ghosts”, “Gentlemen Take Polaroids” – were perfectly balanced points of stasis, as conscious of their construction as of the things they represented. They were like statues of events to be appreciated for what they were as well as what they stood for. They were impressive but cold to the touch, like emotion suspended in aspic.

“I think I was a little insecure writing with Japan,” Sylvian admits. “I didn’t want to make mistakes in public. Maybe because the first couple of Japan albums were so awful, we were so scared of making those mistakes again that we went the other way into manipulating everything. I wanted everything to be precise and I’m still a perfectionist about things but I felt then it was affecting the songwriting in a bad way, it was becoming too sterile.

“My existence, at the time, was so based around the band that I wasn’t allowing any new experiences to reach me, I was sheltering myself far too much. I allow myself to enjoy life more now. I actually take pleasure in doing things that I wouldn’t have allowed myself to do before because I’d have thought it was wasting my time. Now I have the courage to make a fool of myself, if you like.

“My life is dedicated to the work that I do and I lost out a lot when I was younger through not wanting to be bothered with enjoying life but just wanting to get on with the work. Everything had to have a value and it was always to do with the band so maybe it made some of the things I was writing appear shallow.”

David Sylvian became synonymous with melancholy the way Mac [Ian McCulloch] did with arrogance and Bono did with God. It bemused him.

“It’s inherent in my nature. You have to use yourself in the best way you can – all the things you think are your faults as well as the good points. I use my depressions and the isolation I enjoy to my own benefit but when I was experiencing something that I thought wasn’t valuable to me, I’d stop it, I’d just shut it off whatever it was, a person or whatever. I wouldn’t allow it to get in the way of what I was doing and that was definitely a mistake.

“I’m still conscious of what I experience – maybe that’s a fault of mine – but after the split up with Japan, I went through a lot of things that I didn’t want to, a lot of bad experiences and I thought they were useless to me but they turned out rewarding in the end and I feel I’m a better person for them.

“I wasn’t exactly afraid of them, but I just thought that if I went through them, I’d have nothing to give. I feared it might take away my will to give – that’s what I was always afraid of, losing the will to write and I did lose it after “Tin Drum” and I was afraid it was permanent. I mean, you hear stories of people in all types of business where they say ‘I’m afraid to stop even for a week because, if I do, I’ll never start again’ – that’s the feeling I had about it. I really felt that strongly but when I stopped all the frustrations I had about not creating something went into other areas and I became a richer person in that now I’ve got more outlets than I ever had before.”

To his surprise he took up drawing and taking Polaroids, discovering fresh impetus from a chance meeting with one special painting.

“I never appreciated art to any great extent, I just saw it as paintings on a wall and I couldn’t open up. Then I saw the painting by Frank Auerbach (a twisting head like a granite fist in motion) that eventually appeared on the cover of “Oil On Canvas” and it just went straight to me. It was a shock because I’d never felt anything from a painting before and, since then, I’ve learned quickly, going from one painting to another, being able to experience something.

“I don’t think you can take my drawing very seriously from a critical point of view but it’s really good for me at the moment, it’s learning something else again. By drawing you also tend to see things differently and that helps the writing. I’m more observant than I was before, I see things clearly, I see pictures in many things that I may have been blind to before and I know that enriches my life and must, consequently enrich my work.

“The drawings and Polaroids gave me back a naivety that I’d lost – just starting from scratch again – and that tended to translate into the music. I thought ‘Yes, I used to feel that way about music, how can I get back to that?'”

Listening to “Brilliant Trees” feels like a stroll through a gallery, viewing an assortment of images – some brittle like Japan’s, some lusher signs that a new confidence is allowing things to bubble up from within. There’s a yearning for intuition in the lyrics that complements the improvisation and one song, “The Ink In The Well” is exceptionally vivid, and impersonal route to self-discovery.

“Picasso is painting the ships in the harbour/The wind and sails/These are years with a genius for living” …it uses “Guernica” Picasso’s pictorial documentary of the Spanish Civil War, in a far more intense manner than, say, “Tin Drum” used the influence of Chinese music. Sylvian considers Japan’s last studio album a successful, fruitful exercise but “The Ink In The Well” is distinctly more expressive.

“I’ve always been influenced by visual things and recently it’s been paintings – Picasso was probably top of the list. ‘The Ink In The Well’ is not based on the painting itself though, it’s based on the feelings I get from the painting.”

I wonder what Picasso would have thought about the secret life of “Guernica”? I wonder how Sylvian likes it, having people interpret his songs?

“Oh, I like it. I get letters written to me going through the lyrics line-by-line and asking ‘what did that mean? I think it meant that…’ and I always write the same thing back – it’s wrong for me to explain what I was feeling when I wrote the song. The value of a piece of music is to interpret it as the individual sees it. It then becomes a personal thing and you attach it to your life as something valuable, something personal. Pop music is never valuable – it’s entertainment, it’s something that passes over short periods of time and amuses you but a good piece of music or any work of art is something with which you have an affinity and to which you’ll always return. I think it’s bad to derive art from art but if you mix it with your emotions, you feel an affinity with the artist’s frame of mind and you take it and use it to your own advantage.”

The other songs on the album, like the single “Red Guitar”, still play hide and seek with the emotions in comparison with most of the crass stuff it’ll meet in the record racks. It’s obviously not that easy to open up.

“Yeah, I’m a sensitive person anyway but you can become that much more sensitive. You can become aware of every nerve in your body so that as soon as your touched, even physically… I actually don’t like being touched at all by strangers, even now I can’t get away from that.

“I find I’m very uncomfortable in the public eye, being interviewed… or being photographed is worse funnily enough. I’m not really sure why, I just feel uncomfortable in front of the camera. Maybe it’s just because I’m shy and its an unnatural thing for me to be doing but I feel that I’m worse now, I’m more nervous about things that I used to be quite confident about. I used to be able to hide behind things, I used to be able to put up a sort of bravado which got me through interviews and photo sessions and so on quite easily but now I dont have that anymore because I felt it was false. I’m trying to be more… no, not trying because it’s something that should come naturally. I feel I’m being truer to myself.

“I try not to sell myself in any way that I feel is wrong for the true, the real me. The image that I had before wasn’t an image really, it all came from myself – it’s just that I managed to put something up front to take care of everything and I can’t do that now. Many entertainers, show business people, can appear in the press, can be written about in any way whatsoever in any kind of magazine and not feel any personal abuse because they can shut off that side of them when they go home. I can’t shut it off which is why so many things offend me, especially the dailies. It’s their nature to write that way and I understand it but I just can’t stand being portrayed that way.” His antipathy towards the press reached phobic proportions when Japan split and a certain tabloid made a meal of a minor car crash with a front page headline: “Pop’s Most Beautiful Man Scarred”.

“After that car crash thing went in the paper I wanted to separate myself from that image but whereas most people could get away from it I couldn’t because it was me. It wasn’t a pretentious image that I’d built up so trying to get away from it was just like trying to run away from myself. In the end I just had to stop doing the interviews.”

As if the perils of being handsome weren’t enough, there were other insurmountable preconceptions that forced him into hibernation. One was the supposition that just because he had a record in the charts, he must be an entertainer. Sylvian had other ideas.

“That something that’s immediately forced upon you by being a pop musician, something that I’ve grown more and more uncomfortable about. I’m working in the pop field but by being categorised as a pop artist or whatever, I’m lumped together with a whole group of people who have no values at all.”

Although Sylvian confesses that he feels less threatened by withdrawing from his work, there’s a practical reason for his refusal to polish up his profile. Its his belief that essential art must stand detached from its creator in order to assume a potent life of its own.

“It’s impossible when you’re working in pop because your constantly standing up in front of the work and saying ‘This is mine, I created it’ – you’re constantly in the way, crowding the work and people look at you and read the interviews and see the reason before they see the work. That’s really the wrong way round and so, consequently, people aren’t appreciated until after they’re dead, until they can stand down and let the work live for itself.”

If the art of pop is self-promotion, Sylvian’s interests lie elsewhere.

“Tom Conti did an interview a long, long time ago on TV and he was asked why he didn’t do interviews to often and he said ‘Because if people see me on TV, they’ll find the characters I play less believable, they’ll just see Tom Conti’ and he’s right. You can’t see past the image of pop stars, people can’t escape it. I don’t think actors should do interviews then you’d become so much more involved in the roles they play. It’s the same with musicians.”

And people?

“I think you look to find the human element in people, something you can latch onto in a way. When you meet someone, you’re hoping to see an open person, an honest person who is not putting up a front to either hide behind for himself or to fool you. I guess it’s the same with music.

“I never had much contact outside the people in the band before and meeting a lot of new people – normally people older than myself who I feel I can learn a lot from – broadens my horizons. With Japan I felt that I got to the top of a ladder and there was nowhere else to go but now I feel that I’m at the bottom of a new ladder of creativity that has so many possibilities and I want to keep working and climbing.”

To what end?

“I don’t actually think about that. I hope it will have some value but I couldn’t even begin to say what value it will have.”

Wisdom?

“Learning. You have to keep learning all the time, gaining experience, educating yourself about life. It understands yourself. I feel that by understanding yourself, you understand a lot more about the world and other people – or that’s what I always found when I was younger. It’s explaining the self and seeing how far you can go. I feel it necessary to carry on.”