BSide 12/93-1/94

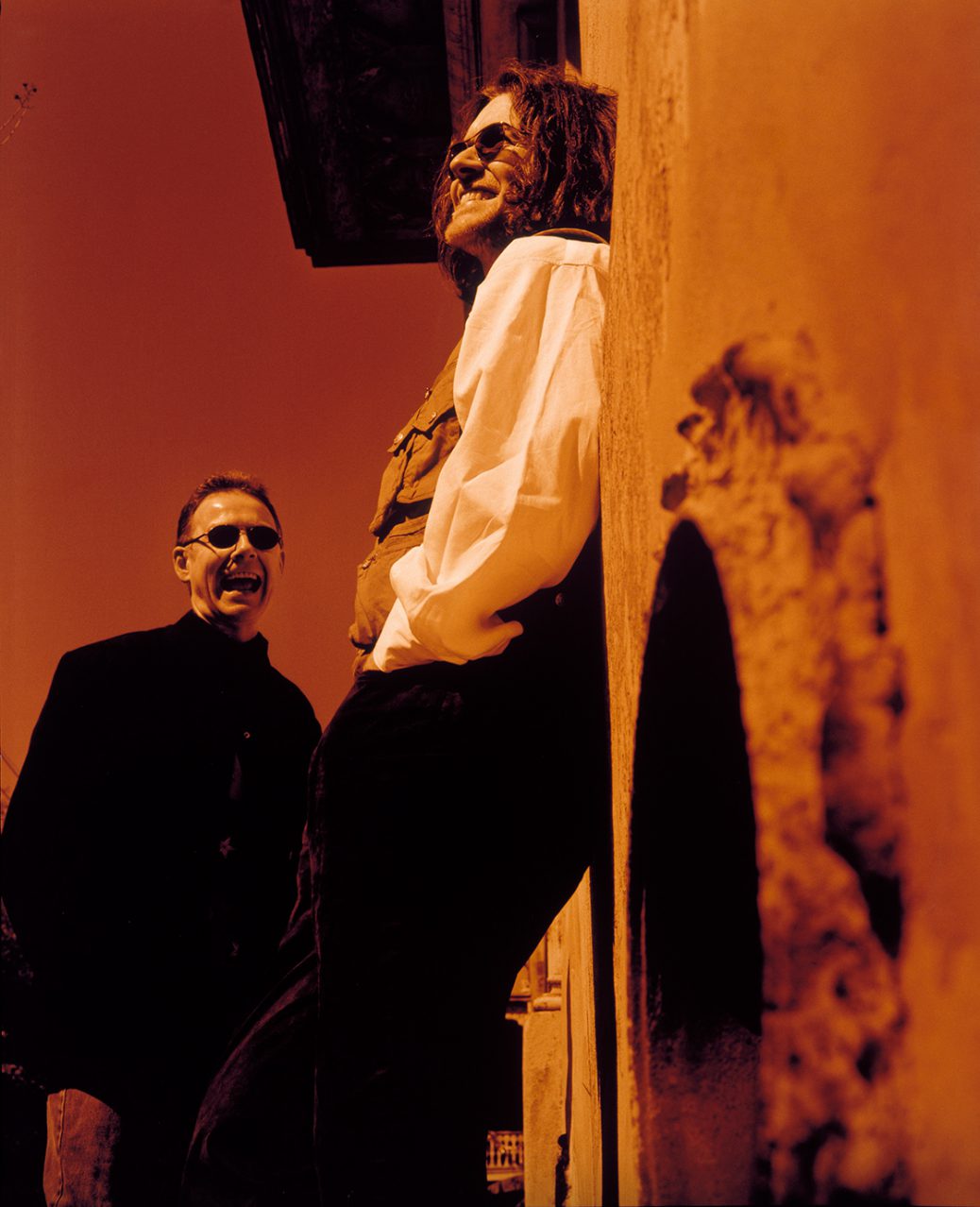

Sylvian & Fripp

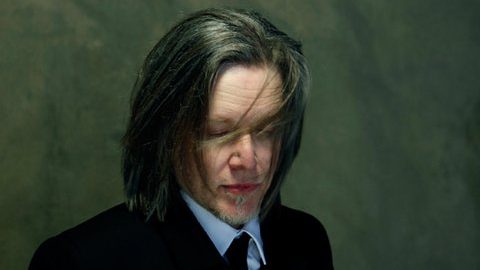

the universal metaphors of enigmatic Sylvian

by Jamie Kemsey

Its brilliance was an intensely colorful cavalcade of reds, oranges, and yellows. Above, smoke blacker than the night hung heavy in the cloudless sky. It was a mile away at least, but I detected the faint scent of death. Something very old was dying and as always in these situations, I watched with diseased fascination, perched atop my couch in the living room of my apartment on the third floor of the timeworn house. The fire came in spurts, reaching to the sky in sudden bursts of freedom, then just as quickly disappearing

This time was different, though I was both dejected and exhilarated. An ancient church was burning down, but behind me a song was building up: “Gonna take a course of action/to restore my sight/’til the heart of motivation/is filled with a golden light.” It was midnight, the evening before I was set to interview the shaman himself, David Sylvian. His new collaboration with guitar sorcerer Robert Fripp, The First Day, was drifting freely throughout the room. David’s recent ethereal work would be the perfect soundtrack for this dark, private spectacle, I thought but this one didn’t quite fit. It starts out questioning, but almost methodically gives way to a dancing, chanting rhythmic celebration of being. As the flames started to wither, The First Day began to flower, moving into territories unknown for the two wise old experimental music sages–another strange and profound moment along the wondrously complex and deeply personal path I have traveled with David’s music since discovering it a decade ago, soon after the breakup of his first serious band, Japan.

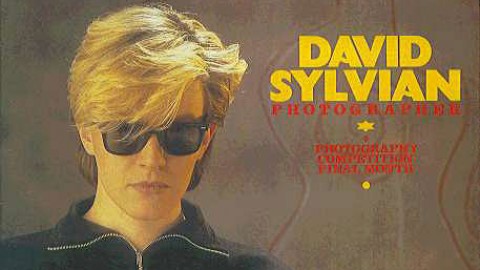

Japan was sprung while David was still a teenager, during the death of punks first snotty wave in late 1970s England. Instead of guaranteeing obscurity by modeling themselves as a second rate Pistols or Damned, they chose the metallic, fashion-conscious glam rock crunch of early to mid 70s Bowie and Bolan. A couple years into it the band suddenly changed course mid-stream, and began incorporating both Far Eastern rhythms and a Far Eastern look. When new wave reared its pouty, lipsticked head, they were often carelessly tossed into the barrel with bands like The Human League and Ultravox. At the genre’s zenith in 1983, they supposedly split for good right after getting serious and beginning to distance themselves from it.

David kept busy, and released his first solo record Brilliant Trees in 1984. A giant leap forward both lyrically and instrumentally, the transcendent Trees marked the arrival of a truly gifted musician, separating him once and for all from the mass of see-through fluff artists of the time. He worked with Robert for the first time in 1985, on the half-instrumental, half-vocal double LP Gone To Earth. In the years since, David has consistently challenged rocks stubborn reliance on the standard three minute crunch of guitar, bass, and drum with work of a quiet, spiritual intensity. From the misty morning tales of reawakening on the 1987 classic disc Secrets Of The Beehive to his eerie instrumental pieces with Holger Czukay, David never fails to dig deep enough to grapple with the questions of life we all must face and the emotions that come with them. His work is a personal document of the never-ending search for answers.

The new decade marked the implausible return of the original Japan line-up for a one off studio project named Rain Tree Crown. Problems surfaced among the band during recording sessions, but the disc received excellent reviews upon its release in 1991. Though it didn’t move as many copies as expected, it may be David’s best work to date. Around the same time, David met Minneapolis soul/pop diva Ingrid Chavez. The two recently married and bought a house in “a nice, quiet neighborhood” in the twin city. They are also parents for the first time a healthy baby girl was born to the couple in late September.

The First Day is David’s first full project since Rain Tree Crow. Though it has his unique stamp on every track, Robert’s guitars share equal billing: he produces a rich, textured landscape of dreams and diversions with axework that is never too showy or technically confusing. To put it simply The First Day is a welcome respite: a rock record that demands an open mind, unshackled heart and wandering spirit (disasters recommended but not required) to be fully appreciated. Just hours after the church fire was finally snuffed, on an unusually sticky late summer afternoon near San Francisco’s Chinatown, I talked with David about The First Day, his relationship with Robert and highs and lows up to this point in his brilliant career.

BSide: The new project with Robert how did it come about? I know you worked with him before. Did you decide then that you would do it again sometime in the future?

D.S.: “We spoke about it briefly. We both enjoyed working with one another in ’85. We were actually talking about forming a band at that time. I guess it was in the back of my mind, with the possible work that finally surfaced with Rain Tree Crow, and it was still in the back of his mind. We just liked putting feelers our; ‘would you be interested again or up for it?’ We stayed in contact during the intervening years, but the opportunity never really arose to work together again until the end of ’91, when he started calling me up again, instigating a number of projects one of which he wanted me to possibly be involved in which was the new King Crimson. We kicked that idea around for awhile, and finally decided it wasn’t right for me, so we went for the collaboration.”

BSide: I listened to the new record a couple of times this weekend and it seems to be a bit more rock and roll oriented than the recent stuff you’ve been doing. It’s not quite as ambient and experimental. Is that because of his influence, or is it a direction you thought you might want to try again?

D.S.: “It was an area we both wanted to cover. It’s more natural for Robert to be working in the rock vein. Prior to Robert calling me in ’91, I was thinking of getting involved in more rock oriented music, because the subject matter I wanted to deal with was more of a frustrated nature. It needed to be backed with a more dynamic form of music. We tried to touch on it a little bit with Rain Tree Crow, but the nature of the musicians in that band it didn’t feel right. When we tried to cover that area it would feel false and uncomfortable. But…at that time we all still wanted to make an album that was more dynamic. So when Robert rang, there was my opportunity.”

BSide: I’ve also recently seen the video for ‘Jean the Birdman.’ How do you feel about making videos? It seems like it is something you are not that comfortable with, like you would rather be buried in a studio somewhere.

D.S.: “I am not crazy about shooting videos but I understand the necessity of them in the business. I’ve taken more active involvement in some of my videos. There’s a problem here though; one of budget. Virgin won’t spend too much money on a David Sylvian video, so I’m limited to a certain group of filmmakers. I worked with Anton Corbijn before he got too involved with U2. We made some weird videos, kind of more Anton’s vision than mine, but I respect them. I’ve worked with some other artists taking a chance, but I’ve felt very unsympathetic towards the results. I guess you could say ‘Jean the Birdman’ is ‘inoffensive.’ I respect the guy that made ‘Jean the Birdman,’ he had a very small budget to work with and produced something visually entertaining I just have trouble with visual interpretations of my lyrics or my work in any way. To me, it’s complete. I’m not like a Gabriel or a Byrne who see the video as an opportunity to expand further. It really doesn’t need expanding further, it is what it is…”

BSide: I feel the same way. To me some of your songs are my idea of perfection, what a song should be, nothing needs to be added. Where does your inspiration come from? Does it come from inside your life? Actual experiences?

D.S.: “Sometimes they are just stories and metaphors to try and convey a certain state of mind or an emotional or spiritual experience. You are dealing with abstracts, and it is hard to pin them down, so I go for metaphors in which the responses will generally be universal. Same with dealing…I deal within a certain context I think I can second guess how people are going to respond to these images, and therefore I will be able to conjure up a certain kind of experience, or mood or emotion. That is very important to me.

“Sometimes the pieces are autobiographical. The whole album [Rain Tree Crow] is so closely related to death and the idea of rebirth, it’s really an album that is like a lament in a way. Something is over, and there is a slight promise on some of the pieces that rebirth will take place. For me the album was an ending in some ways. I didn’t realize how true that was at the time I was working on it. I was involved in a personal relationship which I had held for ten years. Some relationships are bad memories themselves. All of these things came to an end more or less a few months after the album was completed. I was typing up the lyrics just the other day, and I was surprised as to how much they were related to this sense of death.”

BSide: To me, the Rain Tree Crow album sounds more like a David Sylvian solo album than a collaboration, or a Japan album. What was the input of your former mates in the band?

D.S.: “I wrote all the lyrics. I structured most of the songs. I actually find the album is justified by the instrumental pieces because that is where we are really working together, and we all more or less had equal input into those pieces. To me, that justified the whole experience. Everybody worked really hard on it. I think I’ve worked harder on that album than any other to knock it into shape. I really can’t undermine the role that the other guys put into it it’s got some fine performances by all of them. Maybe the best performances on record they have come up with to date.”

BSide: Would you do it again?

D.S.: “It is difficult to say (big smile). I love the experience, I really did. It got a little frustrating towards the end. There was always somebody who wasn’t convinced about a particular piece of music, and therefore I was constantly talking somebody through a piece, so they could understand it and begin to feel at home with it which is very important for me. There was always somebody that was unhappy with one of the pieces. It was kind of amusing. It wasn’t too serious, but it got a bit tiresome towards the last stages of the album, but that really is a trivial thing to talk about. The main problem really stems from the values with which we live by, which guides us in our lives.

“I spent some months with the band prior to working with them trying to get an understanding of the way they thought about the work. I would talk to them a great deal about the way I felt. I thought I made myself clear, and I thought we had come to an understanding of the value of the work, and how it should be presented in the world and how it shouldn’t be compromised. In the latter stages when we ran out of money, there came this pressure from Virgin to release it as a Japan album, and the band went for it. It was in the contract that nobody could use the name Japan so I was actually safe. I had nothing to worry about, except I felt somewhat betrayed by that. We discussed things over and over and over to try and find a solution to the problems, but they weren’t prepared to put up any money to help finish the album, and Virgin wasn’t prepared to touch it unless it was called Japan. So I had to pay for it myself. I took the tapes and mixed the final tracks, and they felt betrayed as a result. They were happy with the mixes, but because I took them and finished myself, they felt betrayed. So we both came away from it feeling that was a very sad way to finish a project that was made in such good spirits.”

BSide: Were you originally going to call it Japan?

D.S.: “No. There were two points in which I was not flexible. One was the method of composition – which was based on improvisation, and the other was we wouldn’t be working under the name Japan. And this was contractual, not to protect me from the band, but to protect me from the record company. It was a sad situation for me after making what I thought was a good album, and the amount of love and enthusiasm that went into making it. I wish a lot of the dirt hadn’t surfaced. I was surprised when it started appearing in the press which I think put a black cloud over the album. People just weren’t interested in hearing it after that, you know? ‘Well, if things are that bad, why should we bother listening to this album?'”

BSide: Do you think it is important for you to break new ground in the States, for more people to hear your work? (We discuss the various stages of his long term contract with Virgin and how this hot/cold decade plus relationship with the label has often resulted in his records being lost in the shuffle on this side of the Atlantic).

D.S.: “I think it is important that you reach as large an audience as possible, because the whole deal here is communicating. Without compromising though. Without me getting involved in activities in which I feel profoundly uncomfortable. I do what I can to promote it, but I expect the record company to do a hell of a lot if they decide to release it. I want somebody to care about it. I think there are people at Virgin now that do care. I am trying to build a relationship with these people now, and we will see how it goes.”

BSide: What if you do have a hit? You’ve never been an artist that has sold a massive amount of records. For me that’s fine, because it’s kind of like my own little secret. For music fans it’s fun because it’s almost like you have this artist to yourself. It would seem strange to me if a David Sylvian record here in the U.S. sold a million copies. Would it feel good to you if it reached that many people?

D.S.: “It would because I wouldn’t have compromised in any way to achieve that level of success. It really would have done it all on its own. It wouldn’t change my approach to my work. I would carry on with what I am doing right now, but with more financial support which is very important. I’ve tried to get a lot of projects off the ground, but they don’t happen because the company is not interested in investing money in me. The financial support would be welcomed, but it wouldn’t change anything.

“My work is of a very intimate nature. If you had my image bandied around, or just my name or whatever, it takes away some of the personal quality I think a lot of my audience feel about my work which I really do appreciate I don’t want to take away from that in any way.”

BSide: You just got married recently. Does this have a great influence on your work also falling in love and going through the process of marriage?

D.S.: “Personal relations are bound to have an effect on one’s life and work. The fact that I am married indicates an enormous change. The fact I am about to become a father indicates an enormous change in my ability to share my life and give. I’ve been so wrapped up in my own experiences, my own work everything in my life has been geared towards the work and my own development. Psychologically, spiritually, whatever…and I guessed I had reached a stage where having gone through a rather negative experience from ’88 through ’90, I began to surface, to realize I had to put a lot of things behind me in terms of relationships. I began to realize I had a greater strength which had been building up over a period of time, which didn’t really happen until finding this out. Meeting Ingrid was a very important time for me, and, at the time, I started working with Robert. His presence in my life has been very important to me.”

BSide: There seems to be a celebratory aspect to the new record. A lot of it is more upbeat than the work you have been doing lately.

D.S.: “We were both coming out of rather difficult, trying periods. Mine was to do with my personal life and Robert’s was to do with his business. When we got to the studio we had a lot of beautiful ballads, quiet stunning pieces in fact. There was this emphasis placed on the more dynamic material, the more aggressive material, primarily by myself. I wanted to deal with this subject matter. While making the album, we were distracted we had plenty of things to be dealing with. Having completed the sequence of it, I realized just the way the album runs was very uplifting. If you made it through the whole album you finally came out of the experience in an uplifted state.

“I am dealing with some rather negative states of mind though. ‘Firepower’ is somebody with a survivors approach to life who is constantly coming up against obstacles which remain obstacles and not opportunities and therefore is defeated by life. ‘Jean the Birdman’ is kind of the same subject matter, but it is more ironic cause it deals with a character that always comes out on top by living with a similar attitude. But…as the album progresses, slightly more hope enters into the pieces until there is this, as you say, a celebratory feeling. ‘Darshan’ is very uplifting.”

BSide: Your work is so original, it is hard for me to pick out influences you might have. When you were growing up, and when you started Japan, did you have influences? I know you started the band when you were very young.

D.S.: “I think the influences were very apparent. We were brought up in the early seventies so there was the whole glam thing going on with Roxy Music, Bowie, T. Rex. I enjoyed that. My sister brought music into the house for the very first time, she is three years older than me: she was listening to Motown and a lot of soul music, and that somehow had its influence. In the latter stages of the 70’s, being kind of alienated from punk, I started listening to fusion music which I don’t have a taste for now but at the time I guess it must have had its influence.”

BSide: It’s interesting to me how an influence like that would channel itself into what you do currently or your solo work in the 80s, because it seems that scene is so far away from what you do now. How do you see yourself getting from that point to here?

D.S.: “It’s a long journey, isn’t it! It took me a very long time to really find what I thought was the value of music, and what it could do. Initially I loved music, and I just wanted to play it. Although it was a pleasurable thing, it also was the only open door on the horizon to get me out of this place this environment which held no other opportunities. In a sense it became a vehicle for me to escape. That was a misuse of music I would say…and therefore there was massive mistakes made. Having done that and looking back on the work we were doing together as a group I don’t see myself in this, I don’t recognize myself.”

BSide: Are you talking about the days when you started Japan?

D.S.: “Yes. We did like two albums and we were deciding whether to break up or stick together and try over again.”

BSide: In the early days it seems as though the band was known as much for your fashion sense as you were for your music.

D.S.: (Laughs) “Fashion sense is a kind way to put it!”

BSide: That is definitely not a knock on Japan. I still love a lot of the later work. But it seems as though the look was really important to the band. People were quite wrongly putting Japan in the same classification as what we called the “new romantic” bands over here Visage, Ultravox, Spandau Ballet do you think Japan’s music still holds up and stands the test of time? I believe it definitely does. There are still many hardcore Japan fans out there that still get something very worthwhile out of the band’s music. Most of those other bands have faded, and you never hear them mentioned anymore, except as a passing memory of that time period.

D.S: “It’s hard for me to say. I haven’t played that material in so long.”

BSide: Because you are now so far removed from it?

D.S.: “Yes. I mean looking back I can say, well, I think we had certain successes which will stand the test of time. Primarily to do with ideas with the arrangements, to do with the production of sound. Most of the contents of the songs themselves were maybe more playful…I’m not really sure. But I felt that up until the time Japan broke, I really didn’t have a basic viewpoint which was stable. It was moving all the time, looking for something.”

BSide: There were a lot of Far Eastern influences woven into the music. How did that come about?

D.S.: “I guess it was spending so much time there. As a band we were pretty unsociable. We knew no musicians in the U.K., but when we went to Japan we met a whole kind of circle we really felt some affinity with, the Yellow Magic Orchestra being the most famous. So we spent a lot more time there and enjoyed working there.

“So I do feel there were certain works that were innovative to a degree, and therefore may stand out. There was also, despite our rather confused state, an honesty about the work. We were what we appeared to be. I mean the way we presented ourselves was the way we were at that time, even if we were a bit screwed up.”

BSide: Changing gears a bit I wanted to ask you about your voice. It is very distinctive. If it was up to you would you rather just do music, or do you enjoy vocalizing and putting your voice on records?

D.S.: “I enjoy putting my voice on records. It’s not always an easy process for me but I think it is important. It’s a limited vehicle but makes the most of its limitations. As we talked about, my work is very intimate, and there is an intimacy and fragility in my voice and it conveys something.”

BSide: Are you the type of artist that enjoys locking yourself in the studio and twiddling with your work and the sounds? I read that Robert was a very spontaneous type of fellow, but you enjoy the labor of it a little bit more.

D.S.: “I do work more laboriously. I care about details. Robert comes from the old school. You go out and tour with material, then you go into the studio and document it more or less. For me the studio is a different place entirely. It’s not the same process at all. I like playing with material. I like taking my time.

“Over the years though, I’ve grown very, very tired of studio environments. They are VERY sterile places. You feel like you are missing out on so much of life. Generally these places have no windows, you don’t know what time of YEAR it is…you use air conditioning all year round. You think, ‘god, I spend so much time in these places I really DON’T want to go in another one again.’ Which is why I search out good locations.” (A large chunk of The First Day was recorded at one of his favorites Kingsway in New Orleans.)

BSide: Do you write in the studio or do you bring in prepared work?

D.S.: “It depends on the project. With Rain Tree Crow there was no pre-written material or discussion of musical direction of any kind. With Robert, about four pieces were written in the studio.”

BSide: How about on the other end performing live? I know you don’t play out too often in America because I’ve wanted to see you all my life, and I’ve never had the opportunity. Do you enjoy being on stage? I can see where it would be hard to translate some of your work live give it the same intimate feeling when you are in a room with a thousand other people.

D.S.: “It’s a problem. I’ve done one solo tour here, but it was beset with technical problems. Generally I’ve not enjoyed touring. I didn’t enjoy touring with Japan. It’s something I grew to dislike over a period of time. There is less flexibility in the music. We didn’t have computers in those days, so we would use backing tapes to compensate for some of the electronics we used on record. We would all be playing along to these tapes and one person would have to go out of beat one time and lose his way, and the whole piece would fall apart. It was rigid, but still was a great sound. Some people have said that people who saw us live as a band thought that Japan had one of the best live sounds they have ever heard. It was very true to the record, but was that the whole point in touring? I don’t think so. In those days it seemed important.”

BSide: You seem to have toured Europe and the Far East a lot more than the States.

D.S.: “I avoided the States for awhile, not in terms of touring, but in terms of promotion. I came here a couple of times, one of them being that time the [Japan] compilation was released. I was offended by the packaging and by the insensitive way the two albums were chopped up and put together, and the way I was touted around. I felt like something on a production line.”

BSide: Would you rather not give interviews? Do you feel the music speaks for itself?

D.S.: “I would still undergo the same process, if it wasn’t two-ended(laughs). No I would…and there are a few reasons why actually. One is that I have to sit here and justify to you, or to anybody that asks me a question, why I’ve done what I’ve done, and why I think it is important that I did it at all. This is interesting. It’s not the kind of thing I sit around thinking about at home, like reason I made a record. Sometimes links are found within the work itself references to myself which I was completely unaware of or whatever, and this is fascinating. There is another level, and that is that I am not a social person. I don’t meet that many people. Like this evening I have to go to some event and meet a group of people and so on. This is a discipline for me, it is a challenge. I always say the world doesn’t need another record, so if you are going to make one, you better have a good reason for doing so.”