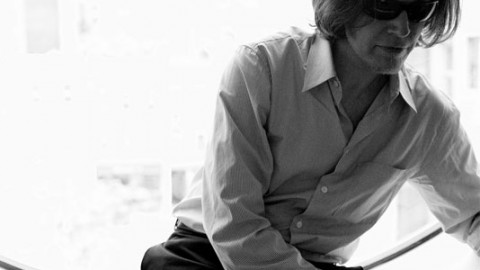

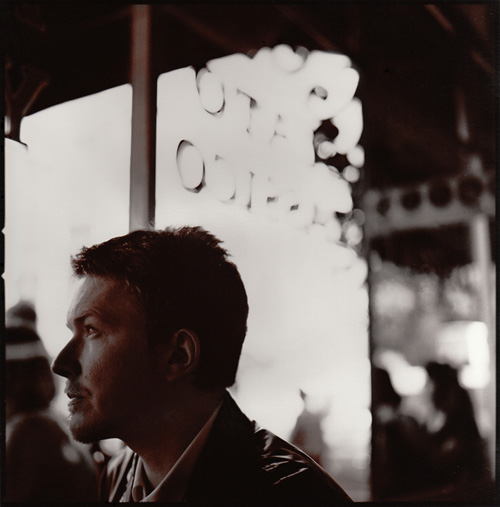

by Dean Kuipers

David Sylvian was literally the poster boy for the New Romantic movement when he walked away from his proto-synth-pop band, Japan, and its U.K. chart-busting album, Tin Drum, in 1982. He had the ethereal voice, the perfect hair, the dreamy lyrics. But he also had experimental music ambitions matched only by his aversion to what he thought were the soul-crushing requirements of pop. The dozen collaborative projects he’s made since then, with top avant-garde musicians including Jon Hassel, Robert Fripp, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and Can’s Holger Czukay, have led him on a spiritual quest that has resulted in his recent solo album, Dead Bees on a Cake.

On Dead Bees, his first solo album since 1987’s Secrets of the Beehive, Sylvian works an exploration of Zen Buddhism and Hindu teachings into his sublime, minimal compositions. Much of its quiet power and restrained virtuosity, he says, flows directly out of close spiritual study with his wife since 1992, Ingrid Chavez. A co-star of Prince’s 1990 film Grafitti Bridge as well as a singer, songwriter, and poet, Chavez has joined Sylvian on an ongoing quest to find “spiritual teachers” all over the world.

The album features old friends, including Sakamoto, ex-Japan drummer Steve Jansen, guitar legend Bill Frisell, and horn player Kenny Wheeler, as well as first-time collaborators guitarist Marc Ribot and Brit-Asian “tablatronica” producer Talvin Singh. Sylvian plans to tour the album, but perhaps not until the year 2000.

CDNOW: You achieve a quiet complexity on this album with apparently very simple techniques.

David Sylvian: It should all be present in the composition. The power of the piece is right there. You try and augment that in the arrangement, not to overstate it or overdress it, because that can also undermine the work.

Is the song, “The Shining of Things,” thematic for the album, in that one of your techniques is to reveal the hidden nature of

very ordinary things?

I think so. That’s the beautiful reward, to recognize the magic in everyday life. It’s a very Buddhist approach, so that’s certainly something I’ve found through my contact with Zen Buddhism over the years. My practice embraces an amalgam of Buddhist and Hindu teachings.

“The Shining of Things” is really talking about a period in my life where I did lose sight of that, to some degree. Some of the people that I’ve come into contact with, some of the beautiful beings who have devoted themselves to God, recognize the divinity of all things. Few of us are able to attain that state, but we can celebrate the magic.

Do you travel quite a bit to find these people?

Yeah. Once we recognized our teacher, it became less important to travel. It became far more an interior journey. A teacher becomes a point of devotion, and that’s enormously beneficial. For years I tried to do it alone, but ultimately I found that the practice dried up.

What is the song “Praise” about? What language is this?

It’s in Sanskrit. It is a song of praise to three manifestations of the Divine Mother. In Hindu mythology, they go by the names Chandi, Durga, and Lakshmi.

Was this somebody [on the song] that you recorded at a temple?

Shree Ma was born into a pretty wealthy family in Northern India, but turned her back on the family and walked into the forests of India at a very young age, and moved into the Himalayan caves for some time. There she became known to the local population as Holy Mother, Shree Ma.

She came to stay with us in Minneapolis. This was a song that she would sing every morning after her morning worship. I had a studio in the house, so it was just a matter of time before I was gonna tempt her into the studio. This was one of the peaks of the five years during which the album was recorded.

Is that kind of purity something one can attain without devoting their life completely?

One has to remain conscious of God or one’s point of devotion. To measure up to people like Shree Ma is impossible. I can only aspire to it. There were times when I thought I could turn my back on music and work towards that goal. People like Shree Ma basically pushed me back out into the world and said, “Singing’s part of your practice. Go sing.”

You’re working with a few new people on this album, namely Marc Ribot and Talvin Singh.

I’d worked with a tabla player in New York, and the session hadn’t gone well. I’d moved to Real World Studios in England, and somebody suggested Talvin. It was wonderful. On the piece, “All My Mother’s Names,” for example, he was performing to a track that already had Sakamoto’s piano and Ribot’s guitar work, so that is quite a challenge. I would love to work with him in the future, if at all possible.

And Ribot?

I was familiar with his work, and when arranging the pieces his guitar playing came to mind. The sessions with Ribot were probably the most productive of all the recording sessions. Everything was done in one afternoon. It was very rich. He gave me a lot to work with.

Is the title Dead Bees on a Cake, a reference to your 1987 album, Secrets of the Beehive?

I didn’t intend there to be a connection. I was kinda reluctant to return to the metaphor. But the mundane quality of the image as it appeared to me was very appealing. It began to represent what people on a spiritual path refer to as the ultimate goal, being the death of the ego and merging with the object of desire. The bee became the metaphor for the ego, and I liked that it was a little bleak and that it had some humour to it. It did resonate with the main themes running throughout the album.