Interview in favor of the remastered and repackaged Japan albums on the 15th September and David Sylvian’s solo work on 29 September 2003!

by EMI. Originally published on the-raft.com, now defunct.

The retrospective covering four of your solo albums and the Japan ones are all coming out in September, why did you decide to revisit the catalogue at this particular point?

It wasn’t my decision to revisit the catalogue. I’d already completed two retrospectives for Virgin, one covered pretty much the solo work, like the past 20 years or whatever of my work that was mainly vocal work and then I did a second compilation called ‘Camphor’ which was the instrumental work of the past 20 odd years. And having completed those two projects I was really done with the past (laughs). I was really happy to put it behind me and just focus on new work, you know. I don’t think an artist should be asked to do this too many times in his life time, I don’t think it’s conducive, to you know, creating new work or even beneficial to the creative mind. Now this was proposed to me that the catalogue should be re-mastered and in a sense re-serviced and I just want the material to be out there, particularly my solo material which I have closer attachment to. You know, just to know that it’s out there and it’s still available, it’s important to me.

R: What was your initial reaction when they rang up and said ‘we’re gonna go back to the catalogue’?

DS: That’s fine; I’m just not gonna be that much involved in the process of putting the whole package together.

R: You have been involved, in the sense of the re-designing of the covers alongside Yuka. ..

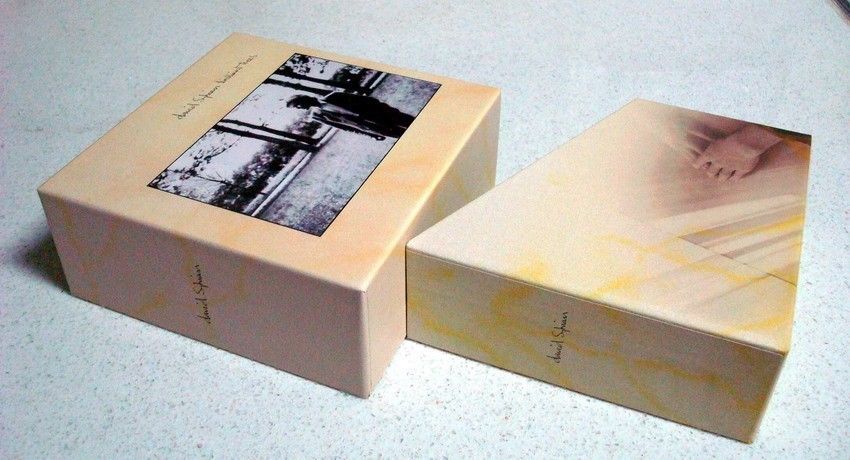

DS: Yeah Yuka been far more involved than I have. I’ve been involved on a very peripheral level just dealing with some images selections and type-face designs, nothing too time-consuming, you know, I guess you could say I was over-seeing the work as it was being developed.

R: Yeah, do you think the new theme with the gold is bringing something to the albums it didn’t have before?

DS: Not essentially, I mean it enhances the visual aspect of the packaging for sure and there are the two box sets involved in these re-issues and they’re quite elaborate in terms of the number of images contained in the booklet and so on and some documentary material. So, there’s that aspect of it along with some of the pieces that are a little more scarce, a little harder to get a hold of. You know B-sides, singles; you know remixes that kind of stuff have been thrown into the package, all the usual really.

R: ‘Brilliant Trees’ was your first album as a solo artist; did you have any specific intention with this album when you made it originally?

DS: Well I think I realised working with the band for so many years, there I was writing new material and not really know where I was heading with it in the sense that I didn’t know who would be performing the material with me. And I was kinda low to get into that right of working with session musicians because, although a confident session musician will give you what you’re looking for they won’t necessarily give you anything of themselves in the process. It’s like a real commitment in the performance which is something you’re used to having when you’re working with a group, everybody’s 100 percent committed to the outcome. So while I was arranging the material I started hearing certain voices, certain sounds, you know, making references between a particular composition and a body of work by another given artist and that’s when I came up with the notion to invite these named artists to be a part of the recording process to see if they too could make connection between their work and the given composition that I was working on. And when, in truth the first time that I used that approach, we all convened in a small studio in Berlin which was foreign territory for all of us it was the first time we ever met or spoke to one another. It was quite an adventure; it was a very exciting time. And a lot of those relationships have grown into collaborations, went on to other projects, so it was a very important turning point for me, if you like, after working with the band for many years it was a really good clear first step.

R: Did you miss them?

DS: The band? (pause) Well my brother was still playing on the album so a couple of the guys from the band ended up on the album on certain tracks so we were still together, still working together. But it was nice that the role was clearly defined, it was my album and I had total control of the direction of the work and that was very gratifying, you know, there was no conflict there as a result.

R: I read somewhere that it was the case that was maybe the turning point in your head about maybe going in a solo direction, is that true?

DS: It was one of the contributing factors that led to the break-up of the group, yeah; just because that was an area of composition that fascinated me that I wanted to pursue to a greater extent but it wasn’t necessarily an area that the band as a whole were interested in pursuing. It was always a bit of an issue coming into rehearsal and think that kind of material and the response was never that edifying. I felt that if I was gonna go down that route, down that path it would be better to do it alone. The material was that personal that it often felt that band would be the wrong context to explore that kind of material in.

R: How do you feel about the success of that album, it was very successful, going in at number four?

DS: The critical response to it was fantastic; the initial response from the public was good. I was aware that a lot of people were buying into it on the back of Japan’s material, that’s all they had to go by and also very aware that a lot of people would come to ‘Brilliant Trees’ and be somewhat put out, you know, not really understand where I’d gone and that was only natural and it wasn’t as accessible as the material I had created with Japan. Although I was pleased by the initial response to the record, commercially, I knew it couldn’t be sustained. I knew it would be very unlikely that it would sustain that level of commercial success.

R: Has that ever bothered you? The fact that life’s guesses come to a choice that you make, so that know you that this is going to alienate some people, you do that willingly do you?

DS: You’re in service of the work really. You do your best to create a strong piece of music and you’re not too worried about the numbers involved in terms of how many people are going to be able to relate to the work. It’s an act of communication so that it is important that it communicates but it may only communicate on a small scale, comparatively small scale. You have to just accept that, embrace that. The important thing is to do the work justice.

R: Is there any favourite track on that particular album?

DS: I stood close to a track called ‘Weathered Wall’ from that record, yeah, it felt like it came someways with the arrangement of the pieces to quite an unusual arrangement it also incorporates performances by John Hassell. It’s really quite something in that context.

R: How did you hook up with Holger , was he the German guy?

DS: Yeah.

R: How did that come about?

DS: Someway as all the connections were made I just asked if they’d be willing to come to the studio in Berlin and participate. And everybody I asked said yes. This is the funny thing. I think people are afraid to ask these musicians to be involved in projects because they just anticipate being turned down and I know now from my position that there are young artists that hesitate before contacting me thinking they’re immediately gonna be turned down. But the truth is that I think people in my position don’t get approached often enough.

R: Have you ever been approached then?

DS: Oh absolutely yeah, for sure. And it’s always wonderful and more often that not I’d take the project on whatever it is. I know that to be true of people like John and Holger, often these people have enormous respect from other musicians, can find themselves isolated somewhat because they’re not invited to participate in projects, I think, just on the premise that it’s just not a possibility, it would never happen.

R: A bit like the good looking girl who never gets the bloke she’s standing there in the corner going ‘why won’t anyone ask me’. Because you’re far too beautiful!

DS: (laughs)

R: Moving on to ‘Alchemy An Index of Possibilities’ – ‘Steel Cathedrals’ and ‘Preparations for a Journey’ were previously only available on cassette does that make you laugh in today’s culture? With the old ipod.

DS: (laughs) There was a hesitation to put them out on anything other than cassette at the time because the initial recordings were made in Japan as part of a documentary soundtrack. And we asked for the material to be sent over to the UK so I could continue working on it for my own project, and they sent rather bad copies over of the original masters. There was a high level of hiss on the main tracks. And I went on to add a lot more instrumentally to these pieces and there was just a concern that people would be upset with the sound quality of these pieces. So in the end we just put it out on cassette because it was more forgiving (laughs). In a sense you couldn’t really tell just how bad the sound quality was on cassette whereas on vinyl it would be a lot more apparent. I’m glad it is out on CD, it was released as part of a box set back in ’91, so it has been available on CD before.

R: Is that frustrating to you that you presumably at some point notice that the quality wasn’t that good.

DS: It was enormously frustrating. I recognised it straight away when we got the copies sent over from Japan but it didn’t prevent me from wanting to work on it because I was really curious about where I could take the piece. But there was nothing I could do to solve the problem at that time, now technology’s improved and you can actually deal with this kind of surface hiss and all the rest of it a lot better than you once could. So it’s possible to clean them up.

R: Has it been cleaned up?

DS: It’s been cleaned up but you can still hear there’s something to be desired.

R: It might be like a phantom limb syndrome for you.

DS: (laughs)

R: Going on to ‘Gone To Earth’ you worked closely with Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson. Was there anything, either mistakes or good practice or ideas or anything that you learnt from recording ‘Brilliant Trees’ that you either did apply or you maybe should have applied looking retrospectively?

DS: I took the same approach which was to bring in these new musicians often meeting for the very first time and speaking for the time on the floor of the studio and that seemed to work again in the context of ‘Gone To Earth’. I mean I should of had a clearer vision for the record, I think, initially I started out recording ‘Steel Cathedrals’, ‘Words with the Shaman’ and then three tracks from what became ‘Gone To Earth’ as an album project. And I was working on all of this material and when I got it to a point of completion I realised that no way did it hold together as an album and so I removed the vocal material and used that as the basis for what was to become ‘Gone To Earth’. So in a sense I was kind of making it up as I went along, it wasn’t an overall vision I didn’t know where I was heading with the material when I started writing it. So I basically used the three tracks that I had which was ‘Wave’, ‘Before The Bullfight’, and ‘Laughter and Forgetting’ as the cornerstones of the album in a sense and continued writing from that point. At the same time as I was doing that I’d found this new gadget, this box which you could multi-track instruments on, mainly used for guitars, and I was writing luke based pieces on this machine. And thoroughly enjoying it and somehow I felt there was a connection between what I was doing with these little instrumental guitar pieces and the songs that I’d been writing for ‘Gone To Earth’ so I decided that I would pull them together and make them part of a double album project.

R: What was it like for example when you meet someone like Robert Fripp for the first time, would that be a nervous type meeting?

DS: I’m generally nervous when I meet most people (laughs). It did seem out of the ordinary. Was it nervous? Yeah I mean it’s a little intimidating sometimes to work with people you have such respect for, obviously. But it was made very easy; he made the whole process very straightforward, very easy. I remember the first thing we did was to record some Frippatronics which he set in motion and said ‘you know we can leave it running for about the next fifteen minutes shall we go have tea?’ You know so that we just left the thing in record and went off and had a chat about you know Goerjeff and all the rest of it which was something else that fascinated me. And that’s where things sort of became very easy, you know, everything seemed to open up. Often it’s the anticipation of meeting people that you respect and admire that builds up this nervousness but as soon as you’re one to one with them that dissipates and you find you’re relating.

R: So you didn’t feel it wasn’t tricky if Robert Fripp had an idea and you said ‘don’t think that’s gonna work’?

DS: No, never an issue for me to tell someone that an idea isn’t working.

R: There are a number of remixes on both discs, what makes you decide to re-interpret the track because obviously it’s not all done but some are.

DS: Yeah sometimes you feel that there’s an alternate perspective to be taken on the mix or it wasn’t mixed in quite the way you originally foresaw it or that it underplayed certain elements that you thought were key to the composition. So you go back and have another track.

R: What was the stand out track for you on the album ‘Secrets of The Beehive’?

DS: ‘Let The Happiness In’. I liked the piece because it was a kind of composition that fascinated me that in a sense I’d been working towards for a number of years where a piece would start off in a rather melancholic place, introspective place but ultimately resolve in a feeling of celebration, so in other words it lifts the spirit through the process of development. And to me that was something that fascinated me for a long time and I felt that I’d nailed it to some extent with that particular piece, it’s the best example of that approach to creating that kind of music. And also I remember writing the piece on a sample keyboard and deciding that it would be best performed by a brass section. And Ryuichi Sakamoto, who was arranging the piece for me, heard it he said ‘this is just within the boundaries of possibility for these given brass instruments that we will select’. So it was a real challenge for the players to actually play the thing it was in the very low registers of their given instruments and they had to sustain the notes for very long periods of time. And we did a very good job, I think it was like a first or second take, but they got it, but it was beautiful and it was great. And also I think that Mark Isham on the track gave one of his best performances as a solo trumpet.

R: Something on each of these three, ‘Gentleman Take Polaroid’s’.

DS: Yeah it wasn’t an easy album to make we just signed to Virgin and they were very keen to have a new album from us as quickly as possible. But it hadn’t been that long before a prior release had been made on a previous label, Quiet Life, and now we didn’t feel quite ready to get into writing new material. So I felt a little bit under pressure to write. The sessions were a little bit difficult; we were kinda searching for a sound for that particular album that separated it from the previous because we hadn’t quite outgrown the previous record. We were having trouble finding that new sound for ‘Polaroid’s’. So it took a while to tap into it but ultimately I think we got there and it’s a much stronger album that I kinda gave it credit for, initially. And also that’s the first time that I wrote material with Ryuichi Sakamoto, the final track on the album is a co-write between him and me.

R: ‘Tin Drum’ your next album was very successful, what was it like living through those times of ‘Tin Drum’?

DS: Strange, because soon after ‘Tin Drum’ was completed we undertook a tour, I think it was the end of ’81 and it was during that tour that we decided it wasn’t working anymore that we were gonna break-up. We had one more year of commitments to undertake and it was during that final year that we achieved our greatest success but it was already over for us. It was a strange place to find yourself in, you never really celebrated the success of the band because it was already over for us. We didn’t announce it until the end of ’82 but, you know, we were living the fact that it was no longer a reality.

R: Was that never a temptation on the view of the success to

DS: To keep it going?

R: Yeah.

DS: No. It wouldn’t have worked, it wouldn’t have worked.

R: Why?

DS: Just the personalities we were sort of pulling in different directions. We’d been together for a while by that time success came kind of late to us. There were other forces pulling us in different directions and you know we were all listening to different voices. Personally I decided it was time, I didn’t want to go on with this. And also just being in that centre spotlight, there were so many pressures even at that level of success. There’s a certain amount of pressure because there are so many people dependent on their livelihood. Their livelihood depends on your staying where you are and so they’re going to try and persuade you to do what they think is best for you in that position. It isn’t necessarily what is best for me artistically, creatively even psychologically, it’s just what’s best to keep the money machine moving forward and I didn’t want that, I just didn’t want to deal with it.

R: Are you proud of that fact that you sort of kept it totally as it should be?

DS: Um there’s an integrity there I suppose. But I’m not proud of the fact that I broke up the band when I did; I had no choice, we all had different priorities in life and mine was really that I wanted to believe in what I was doing.

R: ‘Oil On Canvas’ what do you think the live songs have on the recorded ones?

DS: I couldn’t answer that, I haven’t heard it since we finished it in ’81.

R: You haven’t’ heard it since then?

DS: No, I haven’t heard any of the albums since then.

R: Why not?

DS: I have no interest in them.

R: It’s quite good that isn’t it? From what you remember.

DS: (laughs) So I don’t really know if they have an edge on the recorded ones.

R: Do you enjoy playing live?

DS: I do now. I didn’t too much then.

R: I should mention quickly ‘Raintree Crow ‘, when you and Japan got back together again there were difficulties making the album you say, were there any other difficulties other than financial ones?

DS: Well that brought up difficulties; I think we worked really well throughout the project. It was actually a great time; we had a great time making that record. And it was during the latter stages when we did have problems financing and mixing that we decided to push the same old buttons again and things began to fall apart and felt very wrong. It’s one of the things I regret that we really that we couldn’t of resolve the issues and gone on through a second or third album because I think the first one promised so much. And we were excited by it.

R: Thank you very much for your time; it was very nice to meet you.

DS: My pleasure, you too