The Art Of Everything And Nothing by Justin Hampton (Stereotype, Feb. 2001)

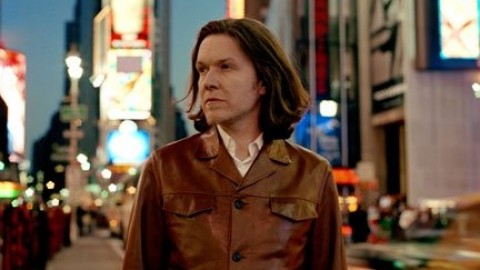

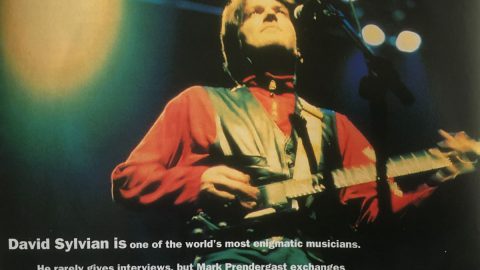

One has to wait a while before David Sylvian is ready to speak about his work. He rarely suffers through interviews, and has only just now decided to revisit over twenty years of work recorded

after disbanding the legendary art-pop outfit Japan. Perhaps it may be because Sylvian has been too busy creating over the years to take much time to explain it-a vast collection of art installations, solo projects and collaborations with the likes of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp and John Hassell attests to it. But Sylvian insists, “Essentially, the work speaks for itself. You really just want people to come to the work, and not have the work clouded by any unnecessary baggage that will come through conversations like this. But of course, that’s not the way the world works. The work has to be publicized and it has to be drawn attention to. You come out and talk about it and hope that people will be interested enough to be drawn to the work itself. I don’t know. I just don’t feel I have much to add to what is already present there in the work.”

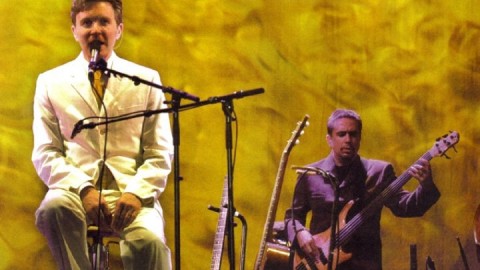

Ironically enough, with the release of Everything and Nothing, Sylvian proves that there’s still plenty to say about his past accomplishments. Those who expected Sylvian to cash in on the New Romantic movement he helmed with the success of Japan’s “Ghosts” were shocked to see Sylvian move on to a more thoughtful and highbrow phase in his career. Interspersing his sparse, minimalist song-based work alongside gentle ambient expressions throughout his career, Sylvian managed to transcend the trends that otherwise would have waylaid him as an artist. Sylvian recalls, “My outlook changed after [Japan] broke up in 1982. Japan was all about artifice, in a way. That mannered style suited the old approach to making music that the band had. But I was done with it, and I wanted to move on. I wanted to find a way of singing, and I wanted to find a way of writing that was more, for want of a better word, more direct, more truthful, less clouded. It’s the same with the writing; I had to find a way of writing that opened myself up, that allowed me to be that vulnerable, because it’s a very public place to be that open about your own life. I couldn’t do it with Japan until we wrote “Ghosts.” And there was something of a breakthrough there, and I thought, ‘Okay, I touched upon something, but where do I go with it?’ It took me a while to find out how to sustain that approach and open up”

Well-mannered and erudite, Sylvian appears more the type to open up through his music than with others. Speaking about his work, he’ll occasionally withdraw into himself to retrieve the answer and speak as much to himself as he will to you. Since his work has often mirrored his own personal life, it’s not a surprise to see Sylvian act this way. “So much of the best work that I do is purely intuitive so it will reflect current interests and passions. But as much preparation as I might do, intellectual preparation prior to the act of writing, come the writing, I have to open up completely and not predetermine where the material should be going. You can set the groundwork to some extent, but when the time comes, it’s a matter of being totally open, and you can be quite surprised by what surfaces at that point.”

The various twists and turns in the music have been inspired by many of the events in Sylvian’s life, from Sylvian’s marriage to former Prince protege Ingrid Chavez to an unspecified personal crisis that accounted for a ten-year gap between the solo projects Secrets of the Beehive and Dead Bees on a Cake. And the changes that these things have brought have also accounted for Sylvian’s changes to many of the tracks on Everything and Nothing, including a remixed version of “Ghosts.” “Compilations don’t work when they don’t have real continuity. You’re thrown backwards and forward in time mainly through production techniques which change over the years. And in my case, my vocal style has changed dramatically over the years. And I just didn’t want to be thrown back and forth, back and forth. I just wanted to create a piece of work as is.

| “Japan was all about artifice in a way” |

People who come to this work as the introductory work, sort of catalog, can find their way in and find the avenue that interested them. But also, that it would stand up entirely alone as a body of work. It’s a listening experience, because ultimately, that’s what you do. You’re riding your car, you’re listening at home, and you just want to be absorbed, overwhelmed by the work, taken in. And I just didn’t want to be thrown back and forth by hearing all these different production techniques.”

From here, the future for Sylvian seems uncertain. He’s hinted obliquely that he may leave Virgin Records (an interview he did with London’s Time Out states that “there’s no way of knowing if I’ll be with [Virgin] three months from now”), and only declares that his next project will take him far and away from the style he perfected on Dead Bees on a Cake. But the means and methods he will explore the next time around matter little to Sylvian. For him, it’s all about communication. “The desire is to have something you wish to communicate. To that end you want as many people to hear it as humanly possible, because it’s an expansive gesture. It’s opening as much as you can. And that’s why I talk about trying to be as open as possible and the work [being] truthful, So if people are good enough to listen to the work, they can ultimately be rewarded with something as a result of giving my work that degree of their attention. The desire is really to just blow people’s hearts wide open.”

(Thanks to Virgin US for providing the material)