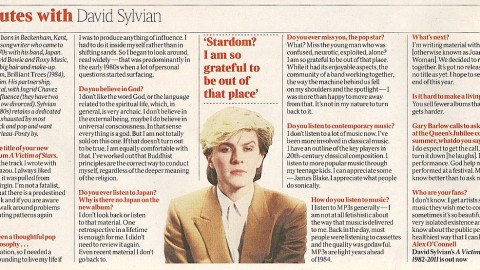

David Sylvian

by Ken Scrudato, Surface, April 2001

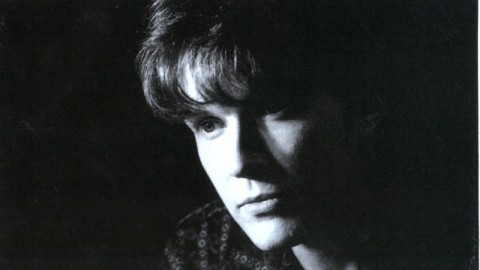

WHEN, IN 1987, David Sylvian sang the words, “I wrestle with an outlook on life, that shifts between darkness and shadowy light,” he spoke of an internal struggle which, at the time, was clearly getting the better of him. The former frontman of post-glam gods Japan, once labeled the “prettiest man in the world” by Rolling Stone and noted for his decadent lifestyle, was trying to escape from his own creation and find something more significant to ground himself in.

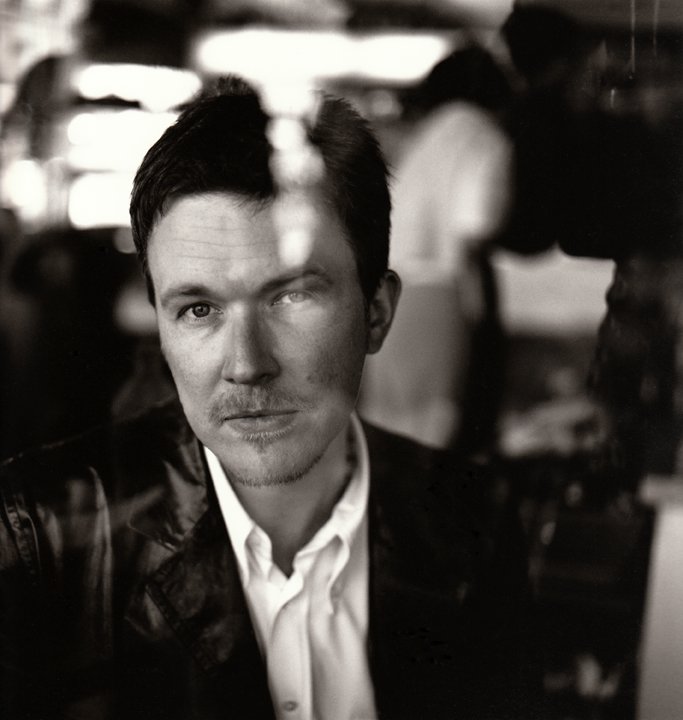

Fourteen years later, however, Sylvian seems to at the very least be on the far side of that shadowy light. With the burden of the zeitgeist left behind, the master of new wave artifice and style has arguably become one of the most prodigious and inimitable artists in existence, with his label, Virgin, clinging to him all these years despite his unlikliness to produce hit songs (drop David Sylvian? never!). And, most importantly…he got the girl.

It’s been an odd journey for Sylvian, to be sure, since the nascent days of his venerable band. Rising from the ashes of glam rock in the late ’70s and warming their hands on the newly burning fire of punk, Japan – at first a failed attempt to become the new New York Dolls, with their combination of mediocre, guitar driven art rock and underdeveloped makeup jobs – actually became one of the most astounding and equivocal centerpieces of the post-punk era. Among the first pop bands to wholly incorporate ethnic influences – Middle Eastern, Asian – into the essence of their sound, they turned out urbane, literary and tremendously forward thinking music. In fact, Mick Karn’s peerless fretless bass musings combined with Richard Barbieri’s lavish keyboard work and Sylvian’s cultivated, enchanted crooning, with heady lyrical references to the likes of Mishima and Sartre, veritably positioned them as the new Roxy Music, though Japan were perhaps more far reaching than their predecessors. If they weren’t terribly influential in their own right, it’s only because few would even dare attempt to emulate them.

After they disbanded in 1982, Sylvian embarked on a solo career that would see him struggle to pull himself out from behind the image he had created during his time with Japan. That personal uncertainty and tension, however, would inspire three landmark solo records during the eighties: Brilliant Trees, Gone To Earth and Secrets Of The Beehive. Further personal problems, however, caused him to abandon his solo work, in order to collaborate with the likes of Holger Czukay, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp and even his ex-bandmates – anything to avoid confronting his own demons.

But then, as if his life were scripted like a film with the inevitable happy ending, Sylvian met…the girl. And within two months of his introduction to the beautiful and talented Prince protégé Ingrid Chavez, the two were married. Most significantly, the two embarked on a spiritual journey that would see them build an entirely new philosophy for living, one based heavily upon Buddhism and Hinduism.

Sylvian returned in 1999 with Dead Bees On A Cake, a stunning new album that was clearly lacking in the disquietude that had fueled his previous work (luckily, Sylvian’s spiritual awakening was not the creative disaster that it had been for his post-punk contemporary, Midge Ure). As well, he gathered a collection of previously released and unreleased tracks for the late 2000 Everything And Nothing compilation, which is a sublime encapsulation of his extraordinary career.

Still married to Ingrid, and now the father of two young daughters, David Sylvian has come to grips not only with the enigmatic ways of the universe, but also his peculiar place within it.

Do you feel like you’re life has been more under control since moving to the States?

“Well I felt that way in Minneapolis. It was wonderful, because I just focused on my family; we’d just had our first child. It was an amazing time, just a wonderful period. And I would just write when I really felt the need to. I was working with Ingrid, as well. Then the whole spiritual dimension came in through us meeting different teachers and took us off in a whole other direction. It was a very rich, happy and eventful period. In contrast to London, where there was always this sense of having to be on.”

Well you can’t let anyone else define what makes you happy, certainly.

“Yeah, that’s true. But, then we ended up living in California, and it was good, but we never had the rootedness that we had in Minneapolis. I guess because we didn’t own any property or anything. And that got stressful after about three years of not settling in or focusing. Then this property came up for sale in New Hampshire through friends of ours, and it just happened to be right by one of the best private schools in America.”

The spiritual aspects of your life and Ingrid’s life are obviously a big influence on your music. And the things that you’re involved in now in certain ways are connected to the existentialism that you were influenced by in your earlier days, but in other ways are very different. I’ve heard you say that wherever you are and whatever you’re going through is where you’re supposed to be. And existentialism was more like, you’ve gotten yourself here and you can change it. Can you explain that philosophical transition?

“Well, I guess it’s something of an evolution. You intuit certain things about life; certain things ring true to you at a given point in your life, and it’s a matter, to me, of tapping into what it is that rings true at any point in time. The focus shifts slightly, or it matures. It got to the point with me where I’d had certain experiences, which made me think ‘what does that mean to me, where does that lead me?’ And I guess that’s when I began to open up far more to the Buddhist way of thinking and to also embrace certain aspects of Hinduism, through my teachers. I ultimately came to that realization that wherever you find yourself is where you’re meant to be. It’s not to say that you can’t change your circumstances; you have the ability to change your circumstances up to a point. But your karma is such that if something wonderful or tragic is going to befall you, it’s just going to befall you. And the nature of that experience won’t be more than you can handle. It will be perfectly in keeping with what it is you’re trying to consciously embrace to allow yourself to move on. If you don’t embrace it, you’ll be running around in circles repeating that experience over and over again for the rest of your life in one form or another.”

So, in other words, you need to face your pain and face your challenges…

“Yeah. Face your challenges and work through them.”

And you feel contented living by that philosophy?

“I think that it’s a philosophy that definitely works, yeah. Though it’s not an easy one to enact.”

Sure, most people would rather ignore or escape from their challenges.

“Well, they think if you ignore it or turn your back on it, it will go away. Of course, the problem that you have to face just happens to be the thing you hoped you would never have to face, because it’s just too hard for you. And you think, well, ‘Why that? Anything but that.'”

You’ve talked about how you went through a very difficult personal period after Secrets Of The Beehive, so obviously you were searching for something then, anyway?

“Yeah, yeah. That was due to the breakup of a long-term relationship which I felt so intensely about – in fact, we both did. It was like losing a friend, like we were bereaved in some way. And yet we both knew the relationship couldn’t go on. So, that had a lot to do with it. It took a long time to work through that. But occasionally within the darkness of my own mind, I would experience glimpses of divinity, and I wanted to go further into that. I wanted to release myself from my current experience, but I wanted to work through it, so I could understand it. When I experienced those sparks of divinity, they made me realize that behind everything, whatever you’re going through – and I was going through some kind of mental torture, some kind of hell – that there is something beautiful. That’s the way I experienced it – it was a lightness, and I wanted to tap into that. As I began to surface from that experience, the opportunity to meet certain teachers arose, very naturally. And for the first time in my life I took the chance and went with it. Being a very private person, a very shy person, I wasn’t really that open to becoming part of a group – even now, I very much sit on the periphery. My nature isn’t to sit at the feet of the teacher. But I felt it was an appropriate time and the appropriate thing to do. I felt that practicing on my own, through, say, Buddhist meditation, not really gong through a teacher, I only got so far in my own development, and then I hit a wall. And it was so solid, I had no way of getting through it. I realized that it was necessary to have somebody to work with.”

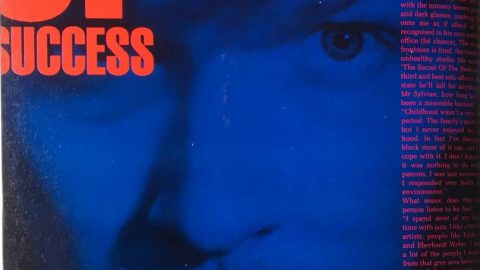

Why is this the right time to release a collection like Everything And Nothing? Is it because you perhaps feel somewhat comfortable in your career?

“No. If I ever feel too comfortable, I get nervous, like something’s not right. The reason it came up now…well, Virgin had actually asked for one about six years ago. Which I thought was just bad timing. I hadn’t released a solo album in a long time, and I was right in the middle of writing, so I didn’t want to face it then. Another reason was the state of the industry at the time, the general instability.”

But what was the inspiration for doing it now?

“I thought that if could persuade Virgin to allow me to bring in all these disparate elements, it could be a really interesting project; and at the same time I’d get to finally wrap up some of these pieces that I thought deserved to be heard. They were outtakes, but not lesser material, by my standards. That’s why it really came to the surface now. It just seemed like an appropriate time. When things fall in my lap and feel right, I tend to not question them too much. If it feels intuitively right, I’ll just follow it through.”

Wasn’t there supposed to be a new Ingrid Chavez solo record, that you would produce?

“We’ve tried to kick-start that one a few times…”

But there’s been too much else going on?

“[laughs] Too much else going on, yeah. It’s really down to Ingrid, when she decides that she has the time to dedicate to writing again. I get the sense that now that we’re somewhat more rooted, for the time being, and the children are a little older, that she will have the chance to shift her focus back into writing.”

Well, it’s been a while, so there are probably quite a few people waiting for that. You were going to tour together, as well, weren’t you?

“Yeah. There’s so many things we would like to do – video projects, film projects, tours. But it depends very much on the financial backing. I mean I’ve had enormous support from Virgin over the years, obviously. But when I want to do something aside form producing another solo album, that doors seem to close, and I’m not given the okay to go ahead.”

The two of you have obviously been concentrating a great deal on being parents the last several years. But people tend to think of having children as something that stifles your creativity or interferes with your creative process and your ability to get things done. Obviously you’re happy being a father, but how do you think it’s affected you as an artist?

“You have different priorities, so music isn’t the be all and end all. And maybe even if I hadn’t had children, there would have been a shift in priorities because of my whole spiritual thing. It’s not that music is less important, it just has to take its place. There’s only so many things you can get to in a day, and music may be one of them. Ingrid’s been wonderful, because she’s put all of her creative energy into the children; that’s been an enormous sacrifice on her part, and the children have benefited from it. There’s actually a very creative environment with the children; we sing together, we paint together, we do all these activities together. And I find that actually very rewarding.”

Do you think the kids understand who their parents are and what they do?

“Um, the seven year old is just beginning to grasp it. She walks into a store and sees a record and says, ‘That’s you!'”

Well, you’re not a policeman or a plumber or…

“But if I am making some kind of public appearance, she’s not really there to witness it. It’s just like I’ve disappeared for a few days. But it’s beginning to register more and more that I make music and other people listen to it.”

Harold Budd, though he’s a bit older than you, recently said that he feels a kinship with the generation of alternative musicians who emerged in the late ’70s and early ’80s – yourself, Sakamoto, Bill Nelson and so forth. He refers you as the new generation of composers, the artists who have escaped the constraints of pop music, at least to the degree that you’ve wanted to. How does that sit with you?

“I understand what Harold’s saying. Everybody has a different way of viewing what they do and putting it into context for themselves. I even have trouble referring to what I do as art, even with a small ‘a.’ For me, everything that’s done in part of daily life, whatever that is, eating breakfast, feeding your children, whatever it is, sitting down and writing a song, is done with a certain presence of mind, a certain level of consciousness, and to me, the music’s just borne out of that environment, that conscious environment, and is just part of my day to day existence. I no longer feel the need to put it into any other kind of context. Because outside of that, it would seem to be role-playing – I’m a father, I’m an artist – and I can’t draw those boundaries. I’m none of those things, and I’m all of those things.”

Which is interesting, because in your earliest days with Japan, there was a lot of play-acting going on.

“Yeah. I was more likely to say ‘This is art’ or ‘I am an artist’ at that point, because it was a bit of a wind-up. Why not? At that point in time, it seemed like it was more fun to do that, to just rattle the cage a bit.”

But you’re happier now in what you do?

“Well, at this point, I don’t feel the need to do any of that, to justify my position or to put myself into some kind of contemporary context that makes sense of where I stand. I don’t know that I stand anywhere.”

But, in hindsight, do you feel like you at least rattled the cage back then?

“Well, not enough (laughs).”

It’s never enough, I guess. But you had a little trouble escaping from what you had created – the monster that was “David Sylvian, singer of Japan”.

“I was always in the shadow of, yeah. Still am.”

And ‘Ghosts’ was the song that first helped you begin to escape. Was that song an instant revelation for you?

“Um, it wasn’t instant recognition. It was a slow process. I thought there was something of a breakthrough there; at least it spoke more directly from my heart. It wasn’t until I got in the studio, and hit upon a way to arrange the piece. Later on I realized that it indicated a direction I wanted to take. And it didn’t necessarily feel right to pursue that direction with the band. It took me almost a year, following on from writing ‘Ghosts’ to continue to write with that degree of openness. I found myself slipping back all the time in my writing and I would just throw out everything. Right up until ‘Forbidden Colours,’ where I thought, okay, this is moving me along the same path.”

Soul-baring is a bit scary, huh?

“Yeah, when you really lay yourself bare, you’re very vulnerable. And you’re not one hundred percent sure you’re doing the right thing. But I realized that I was satisfied with the work, I was committed to it. No matter what other people might say about it, I knew it was an honest statement.”

All these years on, do you feel now that there’s been some path, musical and spiritual, that’s just laid itself out for you, or do you just feel like whatever you’ve done is always a product of just that moment?

“There have been times in my life where I’ve seen that everything’s been laid out very clearly. And I have a great deal of faith in the way the universe works. If something’s not happening, and there’s a great deal of pressure for things to move on, I won’t push it, I’ll wait. But I’ll remain as open as I possibly can. I might even instigate certain actions to see if the time is right to move on, to make the next change, so that I’m able to recognize what the change might be.”

In other words, if it doesn’t lay itself out, that means it’s not ready to?

“That’s right. Like the period we spent in California, where we weren’t sure where we should be in the world. It was a very disruptive period in that respect. It was maybe fun to keep moving around, but ultimately the lack of rootedness was affecting the children, and I wasn’t able to work under those circumstances. So, we began to look for someplace else to live, but it didn’t come quickly, it didn’t come overnight. And as I said, I would know when it’s right, and I did. As soon as that moment arrived, it was so clear. I can say that with conviction. You see, I’m very much aware of tapping into what is and what isn’t the right moment to do something – to make a change, to take a step. I have strong intuition.”

What would happen in the next ten years that would make you feel that life has played itself out the way you wanted it to?

“I wouldn’t think that way, I don’t look at life that way. It’s like carrying around an idea or a direction for a recording project or compositions. The most enjoyable period for me is carrying around this sense that the material is there and ready, and I’ve done nothing yet to bring it into form, into shape. You’re just carrying it with you; it’s like a period of gestation, in which only you and whatever that is…”

Are sort of living together?

“Yeah! And trying to get a sense of what the most optimal form would be when it comes into the world. And the same kind of situation goes along with certain aspects of one’s life. You sense a change is coming and you don’t know what it is, but you’ll recognize it when it arrives, because it’ll have this sense to it. It’s intangible, it’s beyond language, but you recognize it. So, I’m quite patient in that aspect. I have a sense of what the immediate future might bring, but I won’t adhere to it in terms of, like, a concept. I just try to remain as open as possible.”

Do you feel satisfied in terms of…well, are you okay with how big your audience is?

“No. I’d like to reach a lot more people. You know, you create work to communicate, and obviously the desire is to communicate with as many people as you can, because you want to share.”

And this is frustrating to you?

“Yeah, it’s frustrating. But I realize I’m my own worst enemy, because I’ll only do so much to promote the albums. My albums seem to fall between the cracks, though, in terms of like…well, in England, they didn’t want to play a track of mine on the radio because it was too lively for my generation, and not alternative enough to play it on a younger generation’s station. That seems to have been the case with my work all along.”

Well, at lest they’ll never pigeonhole you.

“[laughs] I would say, Harold must feel the same way. His work could be received by a large number of people. It’s not difficult work, it’s very beautiful work and entirely accessible. But he falls between camps.”

He should be writing soundtracks to Hollywood films, I guess. But the world will always consume more of that which is easiest to consume, and as long as you’re okay with that…

“Well, yeah, I try to be. I mean, I don’t have a great sense of anguish about the fact that I only sell this many records. I believe I could sell more, I would just have to go about things very differently in my own life to make that possible.”

Well, you don’t write what would be called difficult music.

“No. I think it’s entirely accessible. There must be something about the work that I produce that I don’t recognize – maybe it’s the quality my voice, or the nature or mood or spirit of the compositions. There must be something about the work that doesn’t allow people to access it in large numbers, and I’m not sure what that could be.”

Maybe five hundred years from now, you’ll be a big star. But what are you going to do next?

“I’m not one hundred percent sure. We’re building a studio now, so I’m not actually writing, but I feel ready to write. And I would love to sit down and start writing without a particular project in mind. I’d like to instigate a number of projects simultaneously. I’d also like to set up the home that we have as a place to invite people to come and work. The place has a very particular spirit, very powerful. It actually used to function as an Ashram. So I think it would be very interesting to have people come stay with us and produce work in that environment.”

And do you have a desire to do something beyond just the music?

“Yeah. I think I would like to go further with film. You know, I’m still painting, but it’s more like a private activity that I wouldn’t really want to make public. But I really think I could bring something to film which could be of interest.”