Rimbaud, Too -The Many Moods of David Sylvian by Sue Peters (Option, January 1992)

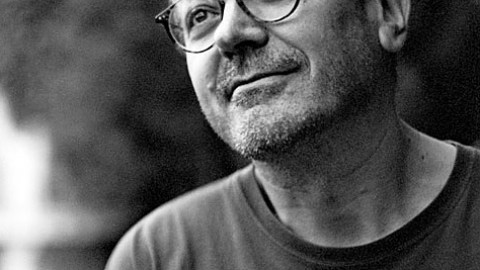

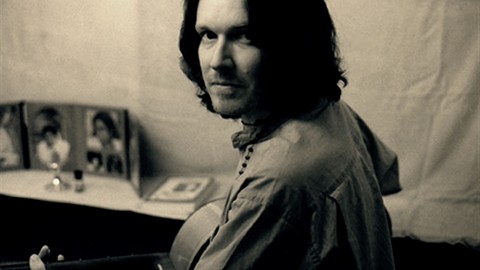

It’s Halloween, and David Sylvian is sitting across from me at an elegant Indian restaurant on Goodqe Street in London’s West End. He’s contemplating a slender wood-bound menu looking for a good vegetarian dish. Slightly unshaven, with long brown hair tucked unimportantly behind his ears and small round glasses framing his blue eyes, the 33-year-old musician looks very little like the formerly androgynous glam-rock pop star who inspired crowds of teenage Japanese girls to screams.

Today, he’s dressed in earth colors of brown, grey and white. The restaurant is busy, but no one glances at our table with even a glimmer of recognition. After years of hiding behind a persona, Sylvian’ s finally found the perfect disguise no disguise.

“I’m very happy about that, because I would feel very uncomfortable,” he says. “I did used to feel very uncomfortable.”

Earlier this morning, I took a train from Paris to talk to the English singer, guitarist, and keyboardist about his mysterious new sound-and-sculpture project, “Ember Glance,” and about the ill- fated reunion of his old band, Japan. But the conversation soon drifts into a philosophical discussion of art, love, and fear. It’s all related, of course, but Sylvian seems more comfortable today easing gracefully from topic to topic.

He, too, was in Paris recently, he says, to record a poem by French poet Arthur Rimbaud, as part of the 1991 centenary celebration of the poet’s death. Over the years, Sylvian has been involved in various artistic projects and has worked with an impressive number of respected musicians. You’d think that recording a single poem would be easy for him, but it wasn’t.

“I was kind of nervous going to Paris to do this project. I was very afraid while doing it: ‘What am I going to do here? This music is playing, it’s got no chord structure, really, and I’ve got to sing a poem.”‘ Sylvian seems bemused by his own struggle with such a seemingly minor task. “‘Could I do it justice?”‘ he continues. “‘Should it be dramatic? Should it be subdued? How should it be done?” I did everything to avoid saying a straight poem. I spoke through walkie-talkies, took one line, edited it; I sang half of it, spoke half of it -anything I could do rather than let it be what I didn’t like.”

A week later, at “Parade Sauvage,” the 24-hour-long music on art extravaganza in Paris an the eve of Rimbaud’s death, there on sale with the bolts of Rimbaud fabric, Rimbaud books, and posters, is the commemorative CD, featuring John Cale, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and David Sylvian interpreting “To a Reason,” a poem, appropriately enough, about “creating a new harmony.”

“I don’t know how good it is,” he says. “I haven’t heard it since I did it. I’ll probably get letters of complaint from people that loved his poetry for years!” He laughs. “That’s what I was afraid of in a way being a kind of upstart singing poetry that I hadn’t really studied. I knew quite a lot of it, but” — he’s suddenly shocked by his own audacity –” in English! I’m speaking it in English!”

Yet he’s glad he tried it, he says, because “after I’ve done it, the fear is really wiped away. That’s what it’s all about overcoming fear .

“Part of being a musician,” he says, is “you have to open up, you have to expose yourself.” That was something Sylvian was afraid to do when he sang and fronted his former group, Japan; and it’s something he has worked hard to change over the years since.

In the late ’70s, David Sylvian (ne Batt) and his younger brother Steve (now Jansen) recruited high school friends Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri and Rob Dean, taught themselves how to play their instruments, and formed a band. In their glam-rock outfits, complete with long, dyed hair and makeup, they made quite a pretty package and caught the eye of Simon Napier-Hell, the former manager of the Yardbirds and Marc Bolan. After being rejected by practically every record label in England, Napier-Hell finally got them a deal with the German label Hansa. (One story has it that Hansa dropped its signees the Cure in favor of Japan because of Japan’s flashier, more marketable image. The Cure were more nondescript at the time, dressed in jeans and leather jackets. Sylvian had never heard this, and remarks with amusement, “Now it’s the other way ’round.”)

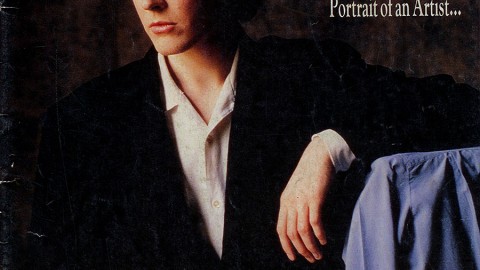

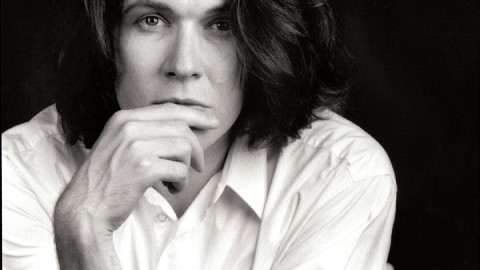

For those who only know Sylvian as a solo artist from his “In Praise of Shamans” tour, which brought him to America in 1988, the David Sylvian of the early Japan albums is almost unrecognizable. Then, he was a 21-year-old with long, bleached-blond hair and painted lips, who scornfully wailed about “adolescent sex and juvenile intentions.” The early albums were positively trashed by music critics as cheap New York Dolls imitations.

“I was totally lost at that point, and desperately struggling to get to grips with who I was and what this was all about,” Sylvian says. “This industry kind of grabbed hold of us and started trying to manipulate us.”

Sylvian is carrying with him a bag of nine CDs he just bought today Julian Arguelles, Jacques Brel, the Lounge Lizards, Steve Lacy 16’s Itinerary, and others. He’s particularly interested in one by Hermeto Pascool & Grupo. “It’s really weird music,” he says. “It’s from Brazil. He’s kind af a genius at what he does. He has records where he plays animals: he plays the pig, he plays the parrot. It’s really wild, but it’s incredible. Good stuff.”

The first record Sylvian ever bought was T-Rex’s “Telegram Sam.” After that, it was “Bowie, Roxy Music, and then jazz.” Japan’s music, Sylvian says in retrospect, “was far too defensive. I guess I was trying to write about emotional states of mind, but I was too vulnerable, and I wouldn’t allow people to get too close to me or my music; or I wouldn’t expose myself enough for people to actually see what was going on. So in the end, the work would tend to be over-processed, in a way.” He pauses to reflect for a moment. “I would say the heart of Japan was an emotional void, and that was my responsibility because I was the writer and that’s what I felt so unhappy with at the time.”

The omission of the first two albums Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives from the Japan CD box set released a few years ago was determined by label ownership rights rather than artistic merit, says Sylvian. “Although I wouldn’t encourage anyone to re-release the early albums,” he quickly adds, with a laugh. “The first two albums were massive mistakes. They were produced under enormous pressure from a whole group of people, and it was like four or five kids desperately trying to get their act together against all the odds.”

After those albums, however, Japan’s music took a dramatic turn. The glam-rock pose turned to more arty musical experimentation. Sylvian says he didn’t get a clear sense of his artistic vision until “very late. I don’t think I really got to grip with it until I recorded ‘Ghosts’ on [Japan’s fifth album, 1981’s] Tin Drum. Then I knew there was a direction to go in. I found myself in some way .”

The cold, distant lyrics and exaggerations of the early efforts which he describes today as “musically, completely uninteresting” and “not representative of anything that we were at the time” are replaced by frank declarations of fear and doubt a haunting, of sorts, which has never quite left him. “Just when I think I’m winning, when I’ve opened every door, the ghosts of my life blow louder than before.”

For the first time, Sylvian allows honest emotion to creep into the music; he becomes stark, vulnerable. The photos from that era show the bowed head of a short-haired, yet still blond, Sylvian, now wearing glasses, one hand grasping his head in profound reflection. Japan was shifting into a direction that had substance. “I was very doubtful as to whether to record the piece because I thought it was very personal and the band never particularly liked the slower pieces. I would bring these pieces to them and get these negative reactions so I tended to think that that’s what the public must feel about them. And when ‘Ghosts’ was successful finally in the U.K. as a single it just gave me the encouragement that it’s possible to be as open and as honest as I would like to be and there’s an audience out there for this kind of music.”

Despite Tin Drum‘s critical success, Japan split up in 1982. The band had transformed musically from Dolls imitators to an innovative esoteric band. They’d been self -taught musicians who had developed a unique style and sound blending African rhythms and Eastern sensibilities. Karn’s distinctive burping fretless bass sound bumped up against Jansen’s intricate and inventive percussion while Barbieri’s moody keyboards and Sylvian’s uniquely textured voice were woven into delicate guitar work .

“When we broke up, I was going through a pretty difficult period in my life,” Sylvian says. “I really needed to find myself I think. I was still pretty young at the time. I had a lot of questions about myself about life and I needed to answer them.” He lets out a slightly sad laugh. “My level of self-awareness grew dramatically over that period and my attitude towards the world around me changed as a result. In a way, I had to find a philosophical standpoint from which to view the world to experience things from.

“Consequently, my attitude towards music changed; its function and what I ought to be giving through music. I felt that music can have a very positive function in society as a kind of catalyst for enabling increased levels of self-awareness in individuals; in helping people to find themselves within themselves.”

It was around this time, the early ’80s that Sylvian, in a cover story interview in New Musical Express, revealed that he’d been reading Siddhartha, Hermann Hesse’ s novel about Buddhism. As Sylvian speaks, it becomes apparent that the philosophies he had begun to explore then are now very much a part of his life and music. He had found a direction to follow, but not without a struggle.

For instance, during the’ 80’s, music industry marketing departments latched onto the “new age” genre bringing into its fold more mystical poseurs than real contemplative musicians. Sylvian’s music was unfortunately lumped in with all the rest and is often played on “new age” radio stations.

“I think the original concept of new age is quite respectable, but what a lot of people think of new age music is not new age at all,” he says. “The problem was that people took the concept too seriously and thought that to be able to help people create a good state of mind, a sense of well-being, all it meant was to get simple sounds, sweet sounds on a synthesizer or harp or something with a simple chord structure, with no darker tones just a lot of pastel colors and that was enough to make people feel good. Of course, people aren’t that simplistic, are they? Even at the height of joy there’s an underlying current. I think to create this music successfully there must be these dark elements.”

These days, Sylvian’s music features acoustic and electric guitar, Satie-esque flourishes of piano, and experiments with taped voices and sounds, over ambient currents of otherworldly synthesized sounds that create the “dark elements” he speaks of. But lyrical coherence, emotion, and warmth are the main characteristics which distinguish his solo work from his past.

Over the years, his attitude towards singing changed as well. On Quiet Life, Japan’s first post-glam experiment of 1979, Sylvian had found a new voice. From then on into his solo career, he gradually let go of the higher octaves and allowed his singing voice to sink within and explore the lower range of his speaking voice. On all of his solo albums, it trembles with a texture and strength that belies his gentle stature. Sylvian often sounds as though he is singing to himself, whispering, or thinking aloud.

“I guess I do that because I like that degree of intimacy, ” he says “because I think the work is talking about something that, in a sense, is very private. To sing this out would be to work against the kind of emotions that I want to work with; if somebody’s listening to it, I want them to almost feel that it’s their voice, you know, speaking to themselves.

“With Japan I was very insecure about my voice I was very insecure about a lot of things and I had to find a way of dealing with that. I had several different mannerisms and tried so many different ways of singing. I finally did away with them all. I still don’t feel actually comfortable about my voice, but that’s on a more professional, technical level. I don’t sing very often. So I get into the studio and there I am; I’m meant to perform, but ifI don’t get it in the first few takes, it may take me a long time… because I have a limited attention span, and I’ve put everything into these first few takes, and it has to be there somehow.” His voice drifts off, as if he’ s anguished by the ephemeral nature of his art.

In 1989, Sylvian’s five solo albums were released together as Weatherbox, a CD set beautifully designed by artist Russell Mills, who also designed most of Sylvian’s album covers and the stage set for his 1988 tour (Mills has also worked extensively with Brian Eno ). Everything from the colors and textures of the paper used, to the design itself the five disks slip into a small bookcase-like box was done with profound care and artistry. And to each disk Sylvian ascribed a symbol of nature: a tree, stone, earth, water, light.

His first solo album, released in 1984, was Brilliant Trees, which contains musical carryovers from Japan: a certain atonal quality to the melody, and his brother Steve on drums. He had already begun to gather some inspirational collaborators, which would eventually grow to include Robert Fripp, Mark Isham, Bill Nelson, and Jon Hassell, among others. Gone to Earth, his 1986 release, is an atmospheric double album consisting of half instrumental and half vocal material. “Sometimes [lyrics] are as important as the music, sometimes less important,” he says. “If you take Gone to Earth as an example, I would say the lyrics work as keys to unlock the emotion within the music itself.”

Sylvian’s chef-d’oeuvre remains his third and most recent solo album, Secrets of the Beehive, which came out in 1988. “It was a very easy album to write,” Sylvian says. “Each song was completed in one sitting, so the material came very quickly… and some of it I was confused by. I thought I was in high spirits and yet I was writing a piece like ‘Waterfront”, which amazed me.”

“Waterfront” ends the album with a quiet statement of doubt and rupture in the last line, which Sylvian sings quietly: “Is our love strong enough?” The song, he says, “was actually kind of a warning of things to come, because my life got much more complicated. That song remains very close to my heart as still being relevant to what’s happening to me now.”

One senses that Beehive has left an unsettling shadow over Sylvian’s next step. What does one do next? “In a way I’ve been in a period of stagnation,” he says, in a vaguely troubled tone. The four years since the album have been difficult, both professionally and personally. Despite the evocative moodiness of the two albums on which he collaborated with German experimental musician and former Can member, Holger Czukay (Plight and Premonition, 1988, and Flux and Mutability, 1989), he dismisses them as “not particularly productive.” On those albums, he grasps for new tools of expression, playing harmonium and vibes.

He is happier with the sound of last year’s Japan reunion under the name Rain Tree Crow. But while the music satisfied him, the collaboration left him somewhat bitter. The project, full of hope on anticipation, left a feeling of unfulfilled expectation for the four music ions involved Sylvian and the others had a falling out. “We’d run out of money as usual,” Sylvian says. Virgin said it would only provide the money to mix the album if the group released it under the name Japan.

“I stipulated from the beginning that it was something I couldn’t do,” he says. “I’d written it into the contract, which everyone had signed willingly. For me, it would have been dishonest to try and sell the record under the name ‘Japan.’ I personally draw a very clear line between the work I did with Japan and everything I’ve done since.”

Never willing to compromise his art despite what it may cost him, emotionally or financially Sylvian paid for the final stages and mixed the album himself, and it was released as Rain Tree Crow, the title of one of the songs. It took a year to sort it all out, and consequently the album was released without much hoopla.

Despite the outcome, Rain Tree Crow “was created with a lot of love,” he says, gently. “It’s a shame that it had to end in that way.”

Sylvian has barely touched the bowls of vegetarian food he’s ordered, but he’s kept his glass filled with wine. The conversation flows effortlessly and calmly, and is punctuated — perhaps surprisingly — by a lot of laughter. He is perfectly willing to be happy, if things would simply fall into place as they’re supposed to organically. “I think, ifI go to New York next month and start the projects I want to get started, then things will happen naturally. I feel that something positive will happen because it’s a change in my whole life. It’s a bit scary, but it’s a good thing. It’s what I need.

“Did you ever hear ‘Pop Song’?” he asks, referring to a minimalist song released on an EP in 1989. Some people he played it for have liked it and say it’s the best thing he’s ever done; others don’t know what to make of it. He sings the curious lyrics over a simple programmed rhythm that stops every now and again. The melody is difficult to grasp. It’s another situation in which Sylvian found himself in an artistic “elsewhere” that takes a bit of effort to catch up to. Yet that’s the direction he wants to go in now.

“I’ve been writing material, but I’m kind of looking for a different vocabulary,” he says. “I don’t want to get trapped in my own kind of idiosyncrasies. ”

Sylvian’s most recent project is a 35-minute CD of perhaps the most eerie music he has ever done. Called Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory (Caroline), it comes in a book of photos from a temporary art installation he created with Russell Mills in Tokyo at the end of 1990. The exhibit explored the inner landscape of recollection, using tempered lighting, Sylvian’s sound track, and sculptures, like weathered boxes suspended from the ceiling and containing shards of objects to invoke memory; objects including coins, bones, a honeycomb, a dismantled violin.

“We were given carte blanche to do whatever we wanted to do,” Sylvian says. “So we come up with ideas that involved sculpture and photography and light and music. Being site-specific, most of it was destroyed at the end of its duration, but it was well-documented in photographs and drawings and so on, so we decided to put a book together with an accompanying CD documenting the whole event.”

Four hours have slipped by, and a waiter collects the bowls that are all still nearly full. The wine glasses, however, are empty. Despite — or perhaps because of — his up-and-down 13-year musical career, David Sylvian still ponders and slightly doubts his abilities. “I can write a melody to almost anything,” he says quietly, his finger tapping on the side of his glass. “I can write to the tapping of a wine glass. That’s one thing I can do.”

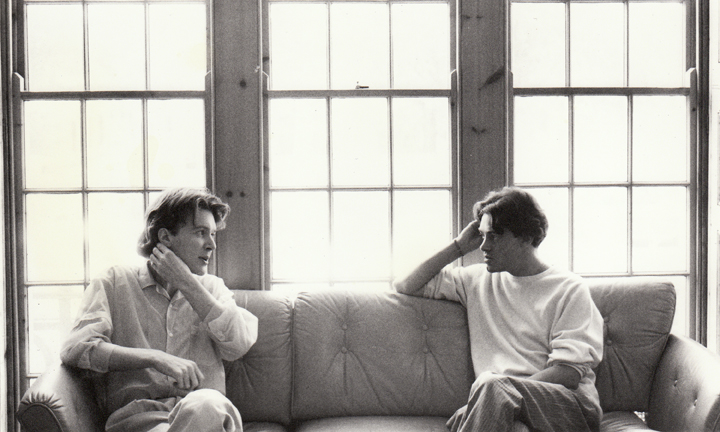

Rain Tree Crow

While some bands keep on churning out albums long after they’ve run out of ideas, a rarefied few have the equally annoying tendency of splitting up as they reach their creative peak. Velvet Underground is an old example, and Jane’s Addiction is the most recent to come to mind. In 1982, it was the innovative, esoteric English band Japan.

Japan’s final studio album, Tin Drum, and come a long way from ’78’s Adolescent Sex, the group’s late-teen infatuation with the glam-rock of the New York Dolls. And the Eastern aesthetic and minimalist of Tin Drum also stood in stark contrast to the onslaught of high-tech synthesized music seeping out of England in the early’ 80’s. Tin Drum featured Japan’s most successful single, “Ghosts,” an introspective, atonal array of synth bleeps, percussion and pauses, with David Sylvian’s deep, brooding voice. Perhaps there was nothing left for Japan to do after that short of complete silence. In effect, that’s what happened, until 1990, when the four members (Sylvian, bassist Mick Karn, drummer Steve Jansen, and keyboardist Richard Barbieri) reformed as Rain Tree Crow. The group’s eponymous album was released last year .

“We wanted to experience being a band. We’d missed it,” says Jansen, from his London home. “In the days of Japan, Dave was in the foreground of all the composing of songs. So it was important that we would all be co-writing the material and that there wouldn’t be anyone focused upon individually. I really wanted the band to write together and to hear the involvement of each musician and not for it to be dominated in any way by one flavor or one character.”

After various solo albums and collaborations with Mark Isham, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Peter Murphy, on Kate Bush, among others the four are now reasonably well-established as individual musicians.

As Rain Tree Crow, the group continues to create highly textured music with an emphasis on sound rather than melody, and eclectic instrumentation. On the album, Rain Tree Crow employs sounds of shortwave radio, water wheel, and Moroccan clay drum, and the squawks of reverberating sax and clarinet replace Mick Karn’s once-ubiquitous fretless bass. Sylvian brings in the improvisational language in which he has become quite fluent since the days of Japan, as well as his distinctive, textured voice, which has become richer over the years.

Jansen shifts his focus to percussion. “Things were constructed around the percussion on this album a lot of the time,” he says. “So there was a kind of looseness and a slightly ethnic flavor to some of the tracks which otherwise might not have occurred if I had stuck to playing the drums.” Barbieri conjures up his familiar burps and bleeps, and the hollow air sounds that fill out the music, giving it a moodiness and atmosphere that always characterized Japan’s and Sylvian’s music. The album is primarily improvised, and was a collaborative effort that took a year to complete.

The result lacks the intimacy that surfaces in Sylvian’ s solo music, instead returning to the eeriness and foreignness of Japan. It’s not easy music, but it grows on the listener steadily over time. The full-bodied “Blackcrow Hits Shoe Shine City” or “Pocket Full of Change” recall Sylvian’s solo explorations. Other pieces including the hollow, whistling atmospherics of the title track and the rhythmic, off-kilter “New Moon at Red Deer Wallow” recapture the otherworldliness of Japan. And that’s where the album is at its best. Rain Tree Crow is not ponderous, as Japan once had pretensions to be, but it fills a darkened room nicely.

Unfortunately for hopeful Japan fans, those old “artistic differences” have cast Rain Tree Crow as a “one-off project,” says Sylvian. “There was very little chance there would be a second album and no chance of a tour, really. My reasons for making music changed dramatically after Japan broke up.” – Sue Peters.