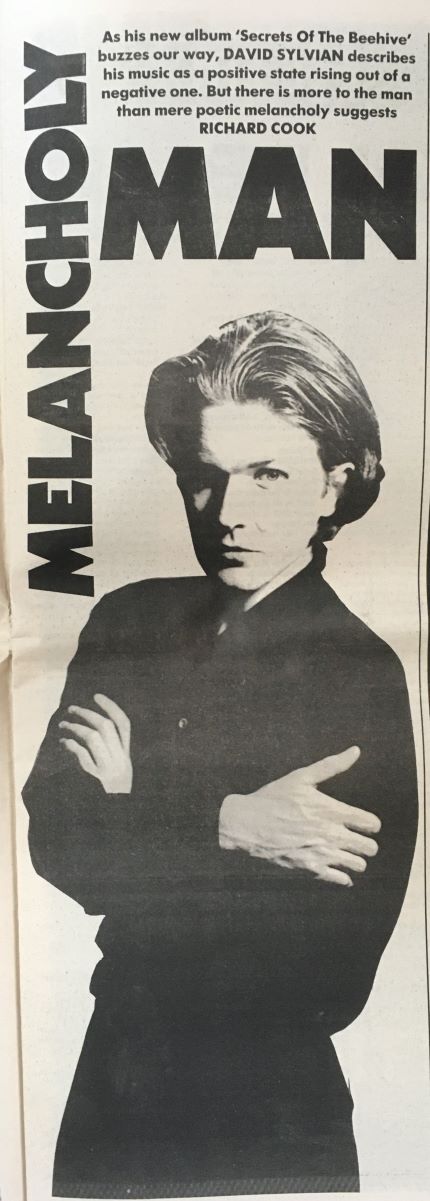

Melancholy Man

Richard Cook, Sounds, 7 November 1987

As his new album ‘Secrets of the Beehive’ buzzes our way, David Sylvian describes his music as a positive state rising out of a negative one. But there is more to the man than mere poetic melancholy would suggest.

The way some people go on about David Sylvian, you’d think he was Buddha, Percy Shelley and Sri Chinmoy bundled into one body.

Few pop musicians have been accorded the sort of reverence that writers thrust upon him.

Why?

“That’s the question that I ask myself,” he says, in what is really a regular, pleasant South London voice. “It might be to do with the fact that I don’t do many interviews and therefore I’m an easy person to mythologise, which journalists seem to enjoy doing.

“Maybe I’m a good exercise for journalists to explore their writing techniques. I hope I’m not really responsible for it.”

He chuckles over it — a very ready laugh. Does he often laugh?

“Mick (Karn) always makes me laugh a great deal, he’s a very funny character. Situations naturally arise where I want to laugh. I laugh quite easily. People tend to think I’m a morose character but I enjoy life a great deal.”

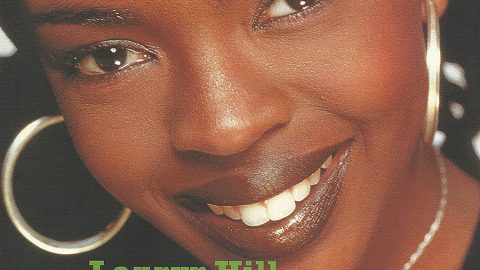

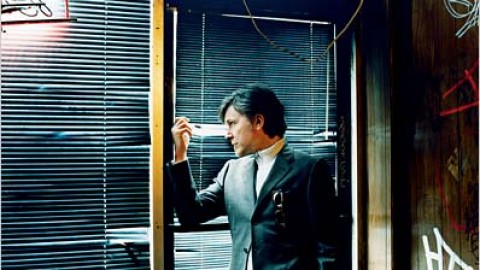

Some of the Sylvian mystique is perhaps not so hard to understand.

His unshaven features are less striking these days — he looks to have the sort of face you wouldn’t wish to disturb because it’s so tranquil. If anything, with his slightly heavy build and jolly walk, he has the demeanour of a big, favourite toy, not the suffering loner one expects.

That expectation is nurtured on his three post-Japan records: the newest, ‘Secrets Of The Beehive’, is about to buzz our way. They are solemn but substantial affairs.

Of all the pale young men of his era, Sylvian has proved to be the most interesting and probably the most talented.

Each of these records has its extraordinary moments; taken together, they’re superbly ambitious, an attempt to create a sophisticated music that goes far beyond the small achievements of the pop song.

Perhaps Sylvian has already delivered his masterpiece in ‘Brilliant Trees’, the first of the three, but the next two are not far behind. If the instrumental portion of ‘Gone To Earth’ seemed a little too wispy to work, ‘Secrets Of The Beehive’ goes the other way entirely.

Sylvian has adjusted the balance so that the songs and the singing hold sway again. In The Boy With The Gun’ and ‘When Poets Dream Of Angels’ there is even a storyline for the song to follow, rather than the usual haze of images.

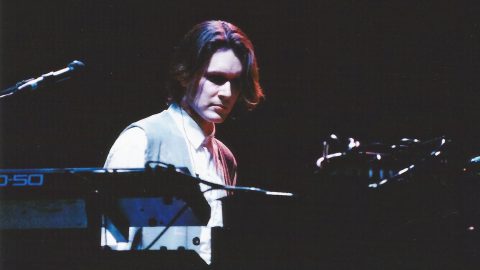

Behind the low, measured croon of Sylvian’s voice there is his meticulously woven music — played by rock people, jazz people, orchestras, machines.

No one puts more attention into the cut of their music than Sylvian: it has the flawless detail of fine porcelain.

“The lyrics are more important than before,” he agrees. “Before they were like keys to help listeners into the landscape of the music, whereas these are more straightforward.

“I wrote each piece in one sitting instead of letting an idea float around for weeks before putting it into some clear form.

“I don’t really like the studio environment. It’s such an unnatural place to have to spend a lot of time in, and it can be hard to recall the emotions that went into writing the music. Maybe it’s four months since you wrote it and then you’re standing there, waiting to do the vocal…”

Taking out his cigarettes, he does seem to resemble a man who’s spent an inordinate amount of time indoors. His hands are so pale that they might belong to some subterranean creature.

“It’s probably a reaction to what I had been doing. I felt I’d taken the ideas that I’d started on ‘Brilliant Trees’ to some kind of conclusion, and it wasn’t worth continuing on those lines any more. If I was going to continue songwriting I’d have to find something else.

“When I wrote the lyrics for Mick’s track ‘Buoy’, the content interested me. And instead of creating atmospheres, I’d try to get lyrics to do the same job. It’s a new way of approaching the work.”

Work is a concept that crops up repeatedly in Sylvian’s output. His records take a long, long time to make; every section is shaped and worked to the finest of points.

If could be music with all the life pressed out of it, but the composer keeps an element of surprise by employing players and thinkers one wouldn’t expect. His cast list for the three records includes Ry Sakamoto, Holger Czukay, Robert Fripp, Kenny Wheeler, Mark Isham.

“When I finished ‘Tin Drum’ I felt I’d written my ideal pop song and I didn’t want to explore it any further. It was enough. As musicians we weren’t capable of improvising — we were a studio band, and we put everything together piece by piece. Nothing was left to chance. I wanted to move away from that.

“But I wasn’t a capable musician myself. I just tried to create pieces of music based on very strict structures and then bring musicians in to improvise over that, to loosen up the frame. And then take away some of the supports and keep adding other things. If you’re using a ballad form, you can do that.

“The strict form gives you much more freedom to take chances and play around without alienating people. who — whether they realise it or not — recognise basic forms of songwriting very easily.”

Sylvian has become a master of that approach. ‘Let The Happiness In’, his recent (doomed) single, begins in glowering brass chords and moves majestically to an exultant climax: it’s a simple piece, but so thoughtfully shaded and finely judged that it seems symphonic in scale.

He describes it as “a positive state rising out of a negative one”; alright, that’ll do.

Sometimes his stuff could use a little more iron, it’s true. The musicians he chooses tend to be pastel players, mild-mannered, not prize-fighters. He sympathises with the view.

Still, as he says, there is plenty more here besides poetic melancholy.

“I hope it isn’t always described as laid-back. I hope there’s always this underlying tension, doubt, nervousness in the music, because it exists within me.

“I find it very difficult to handle pieces of music that are purely romantic, that don’t have an underlying stress. It should come over somewhere.”

Stress, for David Sylvian, probably comes mostly from wondering if he’ll get to work as he wishes. His commercial status is not what it once was, which doesn’t bother him, but does trouble the people who market his records.

He is an eloquent critic of the business which chose to tell him that his last two records were finished, thank you, before he thought they actually were.

One comes across many such artists in this line of work. But Sylvian justifies his pains. He has a brilliant ear and genuine sensitivity. His records tend to make his trouble worthwhile.

He talks of the new climate in the business, of the dreadful good taste of New Age music, and sounds, in his even way, just slightly exasperated with it all.

“I’m kind of optimistic about it,” he says. “It cannot go on this way.”

Laughter.