Life In The Beehive by Richard Cook (The Wire, Nov. 1989)

D A V I D S Y L V I A N sits back and thinks about the work. “There are evident failures and occasional successes, but my opinion of the work doesn’t change much. When I’ve finished something I know if it’s a success or not. It remains. You can hear if it’s incomplete, or if it missed the mark completely. There are quite a few things like that. It’s not very satisfying to go back and listen to it and think, well, this is the past eight years of my life.”

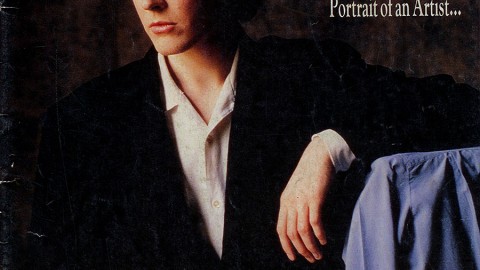

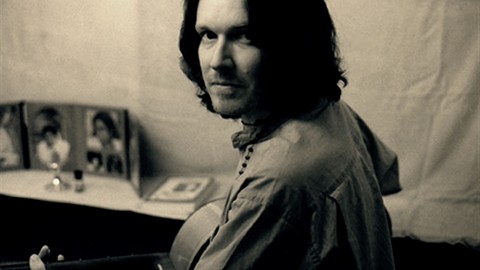

A grudging appraisal. David Sylvian has always been severe on his own work. If Sylvian once seemed created just to be a pop star -the leader of one of the most glamorous groups in the world, Japan, when only a teenager -his path since the demise of the group in 1981 has been as far away from pop normality as can be imagined, while still, nominally, working within that business.

For those unfamiliar with his actions, a recap. Japan made a series of records in the late 1970s that proceeded from a kind of car-crash metal music to an exquisite porcelain sound of electronic hum and rhythm that broke up the familiar time signatures of rock. With Sylvian’s voice as its epicentre, the group steered its huge following in some pretty strange directions: their final big hit, “Ghosts”, was as unlikely a Top Ten record as there’s ever been, a nearly motionless meditation. Their valedictory compilation is titled, wryly enough, Exorcizing Ghosts.

Ever since, Sylvian has grafted together a painstaking and deeply considered series of records. Three albums of songs, Brilliant Trees, Gone To Earth and Secrets Of The Beehive, have been juxtaposed with the instrumental projects Words From The Shaman, Plight And Premonition and the new Flux And Mutability, the latter two a double act with Can man Holger Czukay. Japan were clever at creating Eastern travelogues, but Sylvian’s unorthodox, painterly music comes on as the real thing, a traveller’s notebook, harmonies sketched in, tonalities suggested rather than fixed. The songs are without hooks, often written as single streams of melody; the instruments seem to hang in a kind of freefall, a veil of electronics in the background, a jazzed interplay of guitars and keyboards and horns at the front. Sylvian’s voice rises from a murmur to a croon, and in his grave, uncertain way he’s a compelling singer. His collaborators are impeccably chosen: you’re as likely to hear Kenny Wheeler and John Taylor as Robert Fripp and frequent cohort Ryiuchi Sakamoto.

W E A T H E R B O X I N C L U D E S all of it so far. Collected works are ponderous archives, certainly when it comes to albums marketed as rock music, but Sylvian’s progress is fascinating to follow. Brilliant Trees , though clearly transitional from his older work, is arguably the most engaging of the records: such songs as “Nostalgia” and “Weathered Wall” are at once achingly beautiful and intricate with vaguely disquieting detail. Gone To Earth is harsher, its songs wrestled out, and its instrumental half sounds like a series of unfinished gestures. Secrets Of The Beehive seems crisper, more definite, a sequence where Sylvian examines some other lives and chooses a particularly precise music to go with them. His own singing grows darker and heavier across the records; Beehive’s “Maria” has a subterranean timbre to it. Meanwhile, there are the records with Czukay. They suggest a microphone roving through a laboratory, players and sounds appearing and submerging in the flow.

These aren’t sensational records; there’s nothing in them to shock. Sylvian is peeling off his own skin -there is strong confessional meat in such as “Let The Happiness In” -but he’s doing it with the finest of implements. Often he needs an indulgent ear. In the instrumental pieces especially, the music can drift along without much happening. “Mutability”, for instance, sounds most like a refined variation on one of Eno’s old trance pieces such as “Spirits Drifting”.

“I asked Holger along,” remembers Sylvian, “to be one of the ingredients in the mix for Brilliant Trees. I didn’t know what he’d bring as a musician. As a result he just brought two dictaphones and a bunch of tapes! But he became a very close friend. Plight And Premonition wasn’t something planned -I was there to do a vocal for his record and we just got started on something. There was three nights’ worth of improvising and then I left before I did the job I went there for.

” ‘Plight’ was originally just a ten-minute piece of music which Holger worked on for six months afterwards, adding signals from short-wave radio and stuff, and finally turning it into the piece it is now. ‘Premonition’ is a piece we did at the end of the three days and it’s just as it stood. In the same way, ‘Flux’ is Holger’s piece and ‘Mutability’ is mine. But the way Holger works, he tries to capture the moment which seems to lie right on the line between where you’re dabbling or performing. There comes a moment when you try to find your way, then you find it, and you do the performance. He tries to get you just before the point of performance, so there’s something of the original naivety. It can be frustrating when you feel you can go on to do something much better, but he’s adamant about capturing this essence.

“I dislike studios immensely, but I like Holger’s studio because it’s all one room and it’s geared towards the musician. You never really know when you’re being recorded.

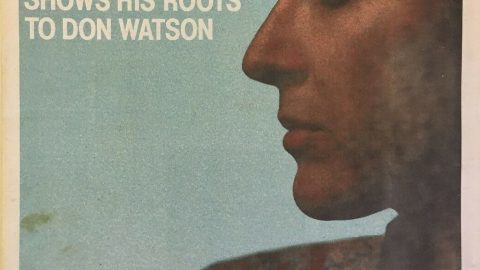

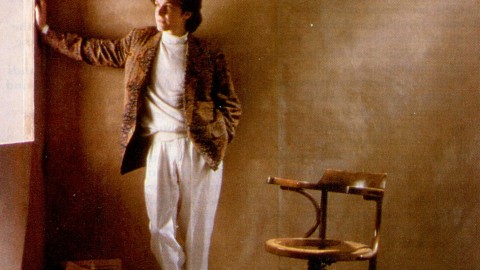

” There’s something unexpected about hearing him profess a mistrust of studios. One thinks of Sylvian as a musician who could cocoon himself away in a studio for the rest of his life, endlessly tinkering and embellishing. Though he now cuts an almost ragged figure next to the unblemished blond immortal of Japan, he still looks shy of sunlight, eyes hidden behind darkened lenses. It’s still amusing to hear a definite South London accent in his voice, and to discover that he’s a cheerful, encouraging conversationalist, not the introspectivo monk which, intentionally or not, he appeared to wish to be.

Still, it was a surprise to see him embarking on a concert tour last year, backed by an intriguing group including Mark Isham, David Torn, Richard Barbieri and Steve Jansen.

“I wish we’d had more time to work together,” says Sylvian “We’d only rehearsed for a week as a full unit and the technical difficulties put the idea of expanding the pieces out of the window for a while. Towards the end things were happening, and we felt now was the time to do pure improvisation, which is what we all wanted to do. But it was too late. If you get one good concert out of ten, I’d say you’re getting somewhere. The rest, you’re coasting along.

” Pure improvisation? Quite a step. Is he frightened by such a prospect?

“It doesn’t worry me. I worry far more about being in a situation where everything is secure and you start to feel complacent about it. I wanted an intensity, because in a two-hour performance if you don’t hit the peak, then you really feel it. You have to feel passionate about it to lift everything else along with you. You hope the audience aren’t waiting for ‘Red Guitar’ for a moment of light relief.

” Sylvian admits that such an internalised view of performance can ignore an audience’s base desire to be ‘entertained’, but that may be his clearest link with the free music that, on other levels, he seems remote from. We need more unpatronising communication between players and listeners: a commit- ment to uncompromised intensity is one way.

“I did the tour because a change was taking place within me. I’ve kept away from writing material, which is why most of the things I’ve done and will be doing are improvised pieces. I had no desire to sit down and write. I’m finding it easier to tap into things with improvisation. A piece like ‘Mutability’ is almost pure improvisation and it speaks a lot for me now. I’m still fascinated by instrumental music and this idea of working at improvising -I’m not technically a ‘good player’ but I enjoy working and letting things happen that way.

T H E I D E A of work -that thing which chaps on building sites do, isn’t it?- seems central to Sylvian’s impulse. It traces through his lyrics as a constant, from “Weathered Wall” (“working at all hours”) to “The Boy With The Gun” (“work has just begun”). It’s the paradox of this music that its delicacy and acuteness -castigated by the unsympathetic as precious or pallid -is achieved through hard labour .

“As a person, maybe I’m more detached from the physical realities than the intellectual ones. I tend to attack things first with the mind. I suppose I’m more of the mind than of the body. So I use references of that kind to the work of the mind . I don’t think it’s a longing for physical work or that I feel divorced from it, because I don’t. It must relate to a kind of growing process -that through action, things happen, and through experience you grow and progress and learn. Through struggle comes knowledge -maybe it’s easier to represent that in physical terms.

” Is this the writer tussling with his angel?

“Well, it’s too easy to write lyrics that are totally abstract, which only you can divine the meaning of. I try to put them in forms which other people can relate to and apply to themselves. Often they struggle to deal with things that it’s very hard to even have a conversation about, something which people have to put into words with inverted commas around them, to try and speak about emotions and thoughts that are too abstract to get a proper grasp of- but which you can grasp yourself, as an individual, as something you’re in touch with. It’s a matter of transforming that into the everyday and not making it fantastic or unreal. Something that is generally a missing, especially in lyrical form, in popular music. It’s something I grapple with. Again, I’m only moderately a successful. ”

If there’s a criticism of Sylvian’s outlook, it could be a a charge of naivety. Next to the average Company concert, an ‘improvised’ set by a Sylvian group might seem profoundly t conservative; to a listener with much jazz experience, this way of working could be elementary stuff. But Sylvian seems as alive to the difficulties as anybody.

“I like to approach things intuitively and in a way I’ve avoided getting into the understanding of past works on a level that would make me approach things in a different way. I’m constantly trying to reinvent ways of approaching the keyboard in a very naive way -the way, when you first sit down at a keyboard, you don’t know anything about harmonies. You just play, and you wait to hear somerhing that makes a decent sound. I like to keep things as simplistic as that, even when working with quite complex tonalities. On the single I’ve just done, I’m using half-tones and quarter-tones, but if I really went into the intellectuality of it, it would take away any intuitive feeling.

“People like Terry Riley and LaMonte Young, I could never approach things that way. People work that way and produce album after album which are all small steps forward in something which they perceive to be important. It has to be done, because they’re the people who are pushing the barriers back. But I don’t work on that level. ”

“Pop Song” is a new single by David Sylvian, unconnected to the other releases, and it brings his work in some sort of full circle: there’s the unshaped electronics of “Ghosts” set around a queer stomping rhythm, a pop song suspended in the middle. Probably no more ‘radical’ single will come out this year.

“It came out of an improvisation,” he explains, “and it felt so out of step with everything else I’m doing, so I thought, why not? I programmed a whole bunch of stuff and improvised with it straight off. It’s interesting. ..I’d like to take the tuning I’m working with now and take it into orchestral things as well as electronics.”

Work, it seems, has just begun.

Weatherbox is released in November by Virgin. Pop Song is available as a single. Sylvian is currently working with the former members of Japan, although, he insists, not as some sort of reunion for commercial reasons. If any recordings are subsequently released, they won’t be under the name Japan. Sylvian’s solo albums are still available individually.