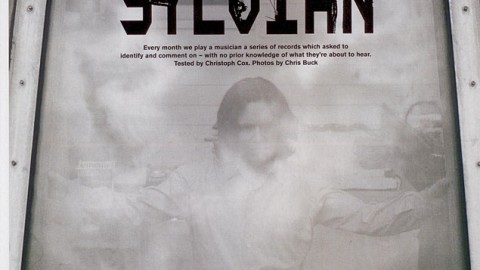

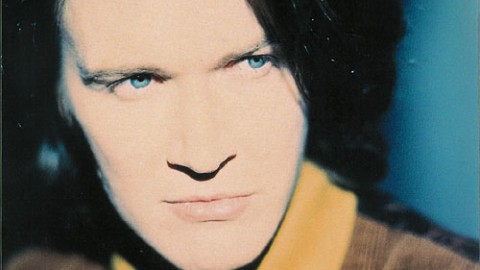

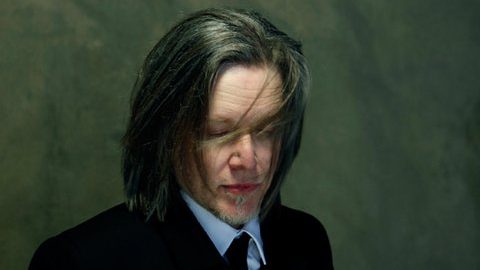

David Sylvian: Japan, Dead Bees and Everything

By Tony Fletcher

December 17, 2001

Though far from a household name, David Sylvian has a resume that rivals those of many more famous musicians. As vocalist with south London group Japan (in the late ’70s and early ’80s), he helped establish a bridge between the art rock of Roxy Music and the synth pop of new wavers like Duran Duran and Tears For Fears. Splitting Japan at the height of popularity in 1982, Sylvian began an esoteric solo career that has yielded just four albums in nearly two decades — which doesn’t mean he’s been lazy or inactive. During that time he’s also recorded a brace of discs with Can founder Holger Czukay and King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, collaborated extensively with the likes of Ryuichi Sakamoto, Bill Nelson, Bill Frisell and Russell Mills, released a number of solo instrumental works, and at the end of the ’80s, reunited with Japan for an album under the name Rain Tree Crow.

In the early ’90s, Sylvian met former Prince protégé Ingrid Chavez at a recording session in New York; the pair were married within months. Following a stint in Chavez’s Minneapolis hometown and then three years in California, the couple and their two daughters now live in a former ashram in New Hampshire. Sylvian recently released a double CD career retrospective, Everything and Nothing, which includes re-recordings, remixes and unreleased songs amongst other selected highlights from his impressive solo and collaborative career.

Why did you decide to change some of your past work for Everything and Nothing? The Japan song “Ghosts,” for which you re-recorded the vocals, is the most obvious example, but you also remixed several others.

There’s a number of reasons. There’s a very simple matter that Virgin owns all this material, and if I part ways with Virgin I may not always have access to it, so having the opportunity to do it was a big draw. Secondly, I’m not that fond of compilation or “best of” albums, because of the lack of continuity: You’re not drawn into a whole experience, you’re just moving piecemeal through the individual pieces, and generally that’s down to production values from different periods in time. I wanted to address that problem, and once I decided to remix this that and the other, there would then be jarring transitions between songs I’ve been doing in recent years and the early ones where the vocal style is radically different. So I thought, why not? I felt that if I could go back to the material and feel rejuvenated by it to the point where I could immerse myself in it and give a committed performance, it would be justifiable, just as if I was giving a live performance. I saw the material as being alive, and so all I was really doing was assisting in its longevity.

Did you offer the other Japan members the chance to change their parts?

That would have gotten very complicated! I think the aspects that dated a piece like “Ghosts” were the vocal styling, the mannered performance, and the production values of that time. There’s lavish amounts of outboard effects, reverbs and plates, which distanced me from the material when I heard it again. So I thought I could bring it up to date. I kept it pure, very clean. I thought about [the 1980s Japan recording] “Some Kind of Fool,” which wasn’t released up until now, and it crossed my mind whether everybody would be happy with their performance but I had to just take what control I had and run with it. Everyone knew I was working on the material and no one objected.

How much of that change in your vocal style has been conscious?

A lot of it has been conscious. Once Japan broke up in ’82, there was this massive change in outlook and approach to the work I was creating. Trying to write more directly from my own experience meant I was trying to pare away all mannerisms or declaration from the work. So I was trying to develop a vocal style that also was true to that philosophy. I was trying to find my true voice, to perform in a very unmannered way, to find means of just letting the song come out. And that meant just letting go — relaxing, trying to hone in on what I feel is the emotional intensity of a piece, and how I can best put that across as a vocalist. I’m looking for something as understated as I can perform.

You referred to doing these remixes while you’re still on Virgin, which suggests you don’t see that relationship continuing too long. Why not?

Because the industry has changed so much in the past few years. I think it’s in the most deplorable state I’ve witnessed. It really hit home when EMI bought into Virgin, and kicked out a lot of good people. The atmosphere in the company changed overnight. There was no one person sitting there who could give me a clear answer to any request. And ever since the takeover I’ve just felt this great sense of insecurity within the label, and I’m sure this isn’t only true of Virgin. There is no security for artists or employees at these major labels and this fearful atmosphere where nobody is really secure of their future doesn’t make for a healthy environment to nurture talent. In fact I don’t see any nurturing going on at all.

Twelve years passed between the times you recorded Secrets of the Beehive in 1987 and Dead Bees on a Cake in 1999.

Yeah, life takes over sometimes. I don’t think people realize that life can become so exciting and interesting that it can draw you away for long periods of time from creating music. And why not? Because it will come back into the work ultimately. I don’t feel the need to prove myself a prolific artist to justify my status as an artist. It seems irrelevant how many albums I put out, but rather the quality that is important. If I make a handful of albums in a lifetime that I can really stand by and say, “that’s work I’m proud of,” I think that’s enough.

What in particular slowed you down?

I got so involved with so many things when I moved to the States, with my family, marriage, children, and then meeting certain [spiritual] teachers, that it was really hard for me to get into the studio and focus in on work. And there were periods of time when I thought maybe I wasn’t going to return to it, because there were other areas of life that were calling. It wasn’t that I wasn’t enjoying music — though the recording of Dead Bees was frustrating and seemed to have numerous obstacles placed in its path along its development. I just thought at some point, “Maybe I’m meant to stop now, and maybe my time is up and I should be focusing on these other elements that are really fascinating me.” But it wasn’t to be so. And I’m really happy that it wasn’t so.

Why did you build your own studio to record Dead Bees?

I just tire of being in the traditional studio environment. I find it totally sterile. And I like to work slowly, and that’s costly. So to have a base where I could work from where it wasn’t costing me anything was a real luxury, and when it was necessary to move into studios or desirable to get a new perspective on the work, I tried to pick places that didn’t conform to the normal standards — that actually have quite a strong spirit. [Peter Gabriel’s] Real World obviously does. Daniel Lanois’ place, Kingsway, has a wonderful spirit.

You set up a hard drive system?

It started piecemeal. We had a couple of ADATs, but we had so many problems with them — we didn’t have one tape that didn’t get mangled and destroyed in the process of recording. At my engineer Dave Kent’s suggestion, we turned to the hard drive as a solution. We started out with something like a four-gig hard drive and a really humble Pro Tools set up and that just expanded as the album went on.

And do you do much in terms of sequencing and using MIDI?

Ultimately everything goes into the computer and into Pro Tools, but I am working with MIDI, I’m working with Studio Vision, mainly in the writing stages, and when working at my own keyboard overdubs I’ll work with Vision, but it almost immediately goes straight to the hard drive.

Have you turned into more of a studio buff than you once were, out of necessity?

I have. When I started out on Dead Bees, I was going to do it with Ryuichi [Sakamoto]. As I took over the production reigns entirely, I got into learning how to handle Pro Tools myself, necessarily so; where other contributors had fallen short in terms of their musical contribution, I had to pick that up and work that out for myself, so I was far more involved musically and on an engineering-production level than I intended. But I learned an awful lot in the process, thoroughly enjoyed it, and wouldn’t have it any other way now.

So the financial investment of setting up a studio pays off in terms of not having to look at the clock?

Absolutely. It’s a wonderful freedom to have. I’ve never been good at working under pressure. I just like taking my time on a project. And having first-second-third bashes at things. I remember getting to the vocals on Dead Bees four years after having written the material. It takes time to work yourself back into the material so that you get the nuances down. I would sing these songs every day until it felt right, until it was coming back at me through the speakers the way I intended it.

Do you draw from a wide range of keyboards in the studio?

Not that much, because I tend to part company with them after a period of time — after I feel I’ve exhausted them. But I have a Super Nova, a number of Roland keyboards of the JV series, a Wavestation, Nord Lead, Waldorf Wave, a few things.

Although you use other musicians, it seems like you could pretty much play whatever you wanted to.

Oh no. I think of myself as a non-musician. I mean, I get by. I can write, and I can perform, to a certain extent, and that’s what I’ve enjoyed over the years — working with non-musicians, and matching that with some beautifully technically proficient musicians that come in and play wonderfully lucid lines and performances and so on. I think of the band Japan as being a group of non-musicians. We’re all self-taught, and although we’ve matured over the years and become more proficient in what we do, there are wonderful holes in our education which will never be filled. And that has meant that when you’re working together in the studio and it comes time for a break — be it guitar or keyboard or whatever — we may not be proficient enough to take that solo, and so we have to come up with alternate means for producing something for that spot. I’ve always found that that creative means of getting round your shortcomings was far more interesting, ultimately, than just whacking out another solo.

You’re also a visual artist. To what extent do you visualize the structure of a song?

The structure of a song is a real internal experience for me. Having said that, I thoroughly enjoy having the ability to go right into a piece of music and fine-edit performances. If someone comes in and solos for me and gives me six takes, I’ll be slicing that performance up for some time, getting it just the way I want it. The same with my vocal performances. I’ll edit it until it feels right. What I did feel about the Pro Tools system was that you could go to town on it, editing material over and over, refining it and refining it without killing the spirit of the piece, and that was not true with analogue tape or digital tape. You could only go so far before you began to lose it.