INTERVIEW / It can’t be him . . . surely not . . .: David Sylvian was a big success as Japan’s bottle-blond, mascara-heavy crooner. After that, as Jim White found out, he went natural

JIM WHITE

Thursday 24 June 1993

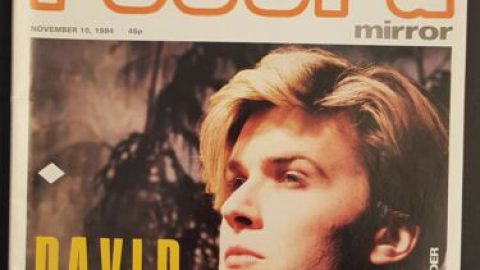

1983 WAS a great year for British pop music, perhaps the last. Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Culture Club, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Wham], The Eurythmics . . . it was a distinguished list of young groups making their way to the bank that year. But perhaps the most innovative was a group from Beckenham in Kent, home of the Beckenham Arts Lab, David Bowie’s act of Sixties pretension. With the escapism that was their trade-mark, these suburban lads called themselves Japan.

At Japan’s core was a pair of brothers, who, sensing that you don’t get out of Beckenham with the same surname as the man who sound-tracked The Wombles, changed their names from David and Steve Batt to David Sylvian and Steve Jansen. The two started the band at school, and had been through a variety of incarnations in the late Seventies before teaming up with the shrewd management of Simon Napier Bell and arriving at a mix of electronics and androgyny which caught the romantic mood of the early Eighties.

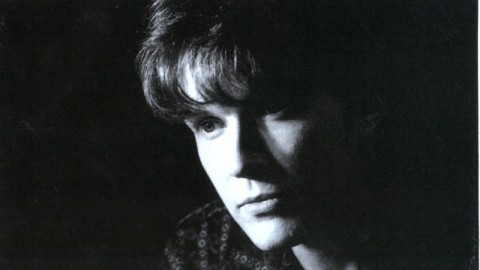

While Jansen tinkered with the computers, it was Sylvian who provided the androgyny. A waif in Mao fatigues, a flourish of bottle-blond hair, face slapped with foundation, he had a vocal phrasing which would have been familiar to anyone who had heard Bryan Ferry.

In 1983, things looked good for the Batt brothers. Their album, Tin Drum, was many critics’ choice of the best of 1982, they scored three Top 10 singles, their European tour sold out theatres from Rochdale to Rotterdam. But, poised on the brink of the big time, they fell out, broke up acrimoniously and kissed farewell to the banking of some very sizeable cheques. Not to mention the dating of drop- dead models, the sinking of large yachts, and the first-naming of royalty, which became their contemporaries’ lot.

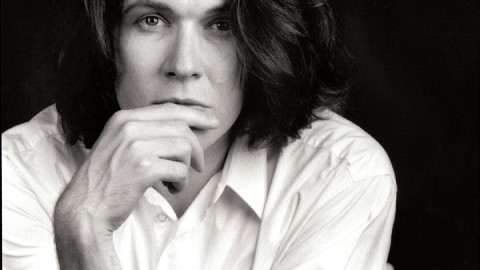

Ten years on David Sylvian, his hair grown mousey with age, his affection for the make-up department of his nearest Boots long gone, does not appear too disappointed with this turn of events.

‘Let’s just say I was not as ambitious as some of the other people who were around at the time,’ he said. ‘In fact, we’d agreed to split at the top end of 1982. We went through most of our moment of fame knowing we were not going to last. I was very uncomfortable with the fame. At first, I admit, I had actively encouraged it. Then, when it arrived, I discovered it really wasn’t what I wanted after all. When I found the work didn’t satisfy me either, I thought, well, none of this is worth the effort. I needed to move on. It was not, er, a constructive time.’

Thus Sylvian did not turn out like Simon Le Bon. In fact, for some time after the fall of Japan, he did not turn out like David Sylvian either.

‘During the lifetime of Japan I became very neurotic, very paranoid. After that period, I re-evaluated everything; my life, my values,’ he said, as if auditioning for an episode of thirtysomething. ‘It was a very traumatic period in my life, which lasted four or five years: spiritual and mental crisis. I was floundering under the weight of things, I abused people that I cared for. I was in the dark.’

He had been ‘desperate’ to escape Beckenham, had done so with Japan, and now needed a further escape hatch. He found comfort in the East. ‘It’s very difficult to single out precisely what influence the Orient has had on me,’ he said. ‘Are you taking something on board, or are you revealing something that’s already there? I learnt that art has to connect us with part of ourselves that is suppressed in the more survivalist aspects of life. And that an artist must be more and more receptive, and allow images to pass through him.’

So you can take it that it wasn’t the latest Japanese computer arcade games that attracted him.

‘And I realised I wasn’t in control of anything during Japan. The music became a way of fighting back against the pressures brought to bear on me. Thus the music became kind of caricatured. I wanted to take control. Now I have control. I need to know everything about anything which has my name on it: a press release, advertisement, anything. What I am describing here sounds like a control freak. But I like to think I’m more relaxed about it than that.’

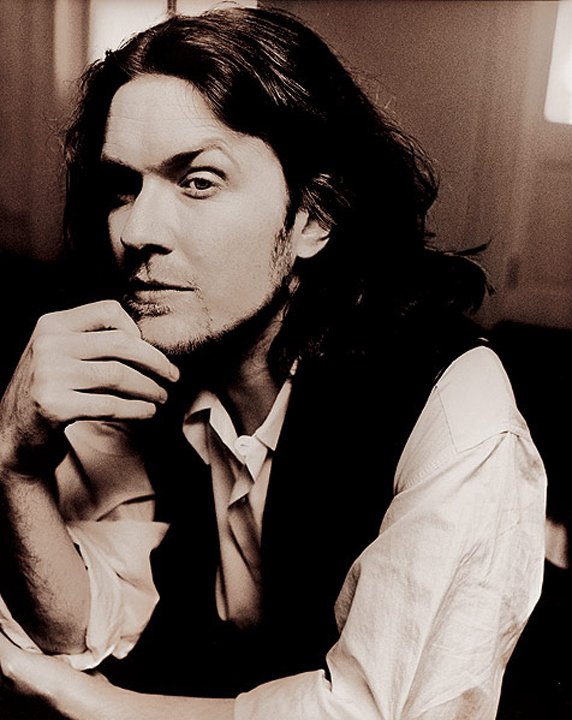

Indeed, compared to the nervous, distant figure he cut with Japan, these days Sylvian appears decidedly laid- back. In conversation he does not move much, sitting calm and still, his words measured, considered. His music is equally contemplative, melodic, slow: the sort of thing unlikely to fill a dance floor even at an office party of Transcendental Meditation experts. His artistic output, too, is decidedly unfrenetic. In 10 years he has managed a couple of solo albums, some collaborations with the Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and a brief reformation of Japan (whom he renamed Rain Tree Crow, anxious not to look back into an unhappy past). Hardly Van Morrison levels.

‘I work laboriously,’ he explained. ‘I like to explore a lot of textural, arrangement aspects in the studio. I try to leave things as open as possible before going into the studio, which becomes expensive, but that for me is the enjoyment of the recording process. When I start a piece of work it tends to be drawn from some kind of visual landscape. Until a piece starts to reflect that same kind of imagery, I know it’s not complete.’

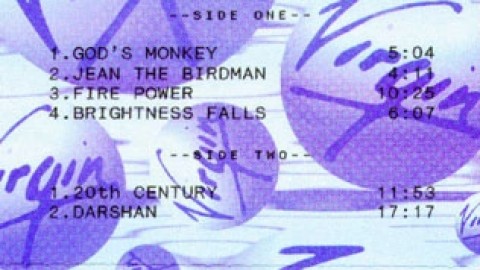

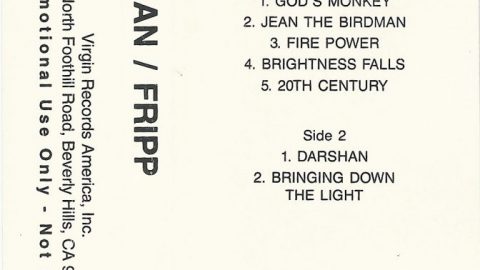

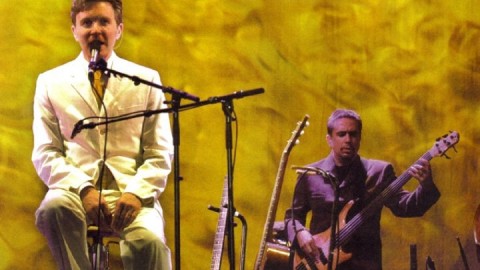

His latest work is The First Day, an album with Robert Fripp, once of King Crimson. Sylvian plays guitar and keyboards, Fripp much the same. Several of the tracks are electronic in the mode of Japan, but others are as surprisingly uncluttered as Sylvian’s physical appearance these days: acoustic, melodic, as if the new romantic had transmogrified into an old folkie. Sylvian first thought of collaborating in 1986, but, characteristically, it took him a while to manage it. Fripp has encouraged Sylvian to return to the stage, a place he admits he does not find comfortable (‘I don’t like being the centre of attention’). The pair’s concerts are, like Sylvian’s work in the studio, largely improvised. On the few dates they undertook in Japan and Italy recently, they had no idea when they walked out into the lights what might happen, even what time they would finish their night’s labour.

‘It can lead to a very brief performance,’ Sylvian said. ‘It was all over after 45 minutes one night.’

Another evening Sylvian found himself confronted with his past. He felt moved to play an acoustic version of ‘Ghosts’, Japan’s biggest hit.

‘It was the first time I’ve touched it since 1983,’ he said. ‘It was quite nice because it somehow satisfied the expectation of the audience that I should play something from my song- book. Generally I don’t listen back. I see what I have done since Japan as a body of work built upon the same basic foundation, I can see the motivating principle behind it. Maybe some of it works better than others, maybe it doesn’t. Who knows. I can’t see the same principle at work with Japan.’

Japan, it seems, will not be revived, however much the nostalgists might crave for it. Try as he might, Sylvian, now cheerfully married to Ingrid Chavez, the Prince acolyte, and settled in Minneapolis, can find nothing to recommend the idea.

‘You know, we made no money out of Japan. It was a real struggle to get by. I am still in debt to the record company. The way I work, I imagine that is a situation that will continue for some time.’

‘The First Day’ is released on 5 July.