Pitchforkmedia.com has posted a lengthy interview with David Sylvian from this fall, where his divorce, Blemish, his past work, his attitude on touring, and what it’s like to work deep in the woods of New Hampshire.

Story by Chris Dahlen (not online anymore)

Mon:12-05-05

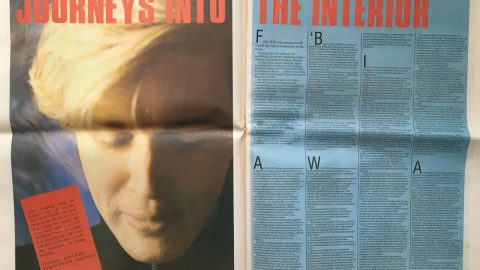

Interview: David Sylvian

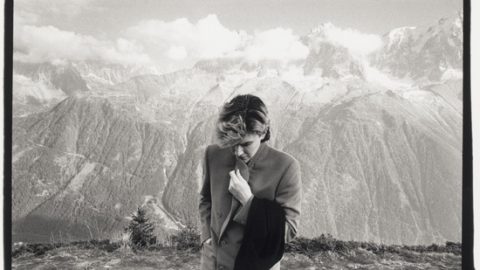

Even when he was a pop star, David Sylvian didn’t want to play the role. Sylvian formed Japan at the end of the 1970s, with Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri, and his brother Steve Jansen (both Sylvian and Jansen changed their names from Batt). As the frontman and main songwriter Sylvian adopted an image that was luminescent, mysterious, and androgynous, with a mane of bleached hair that influenced both Nick Rhodes and– reportedly– Princess Diana, and he led a band that took pop forms and insinuated its way beyond them. That approach yielded their biggest single, “Ghosts”– a ballad with an almost ambient backdrop of plinking sounds and smeared colors, which made it to #5 in the UK.

But that single– and personal conflicts in the band– persuaded Sylvian to break up Japan and work on his own. In addition to instrumental and ambient projects like Plight and Premonition with Holger Czukay, his principal solo albums of the 1980s stretched pop songs into longer forms and ambient passages; Sylvian’s baritone carries the melodies, but the pieces are defined as much by atmospherics as writing.

Although Sylvian worked sporadically throughout the ’90s, his 2003 album, Blemish— the first release on his own Samadhi Sound label– may be the most powerful album he’s ever recorded, the rare case where an artist uses his maturity to show more pain than he had in his youth. Like Johnny Cash recording for Rick Rubin, or Kristin Hersh on The Grotto, Sylvian reveals more because he can endure more. It’s a difficult record even if you don’t know that Sylvian made it in response to the emotional stress of the end of his marriage.

Sylvian now lives in the woods of southern New Hampshire in the former site of an ashram, doing most of his work in the barn that contains his home recording studio. Since he moved here in the 1990s with Ingrid Chavez and their two children, he has worked in the barn, mostly alone, collaborating with Jansen or with colleagues around the world via the Internet. When I went to meet him at a bed and breakfast in Manchester, N.H., I expected him to come out of the woods almost like a mystic– maybe with the long dark hair he sported through the late ’80s or some kind of knotty, free-flowing beard. Instead, he’s a clean-cut gentleman who pulled up in a four-wheel drive vehicle and spoke articulately, and honestly, throughout our interview, and his precise English accent sounded smaller and much more mortal than his singing– a good thing too, because it would be hard to conduct an interview against such an indomitable voice.

Pitchfork: I understand that Blemish was a fairly quick project.

David Sylvian: It was enormously fast, yes. I gave myself six weeks, and that’s as long as it took. Two weeks in, I had the title track, “The Only Daughter”, and a couple of other pieces, and I could hear where it was going. Two weeks in I contacted Derek [Bailey], so within a week of speaking to him I had that material to work with. When I wrote “A Fire in the Forest”, I was already in contact with Christian [Fennesz]. So it moved fairly quickly. Within a week of his receiving it he was finished and he’d sent it back.

I wanted to get into those difficult emotions, and penetrate them as deeply as I felt I was capable of doing, in the security of that working space. So although there were elements of my life that were bringing all these negative emotions to the fore, what I was doing in the studio was taking them further– whereas in life we try to restrain them, we hold them back. We don’t allow ourselves to go too far with it because they feel dangerous, they feel threatening.

And because it was all very immediate– writing and recording the music, lyric, and vocals simultaneously — there was no time for self-editing. I just went straight in and committed to going with what surfaced.

But that whole process was very exciting. It was very immediate. So there’s this dichotomy where I was really enjoying the creative process. Living through these emotions was very difficult, but finding a voice for them was so cathartic, and after that six-week period, I’d felt I’d worked through some very difficult emotions. I felt an enormous amount of release.

Pitchfork: What were the emotions that sparked it?

Sylvian: Well, a lot of it had to do with my relationship with my wife. We were going through a lot of problems, we were in the process of breaking up, and it was in the most intense period of the break-up. That was the primary force. It was very disturbing, and very upsetting, and there was no release for it in any other aspect of my life.

I don’t think I’d ever worked with a complex set of emotions that hadn’t already reached a point of resolution before. This time I was right in the heat of it, there was no resolution, there was no way of projecting that onto the material– an artificial sense that everything will be all right in the end, everything resolves, everything is okay. There was none of that with the material. It was in the heat of that complexity of emotions, of trying to face them head on and not look away.

That generated the emotions that needed to be expressed, but as I said, I tried to go much further with them when I was in the studio environment. So if I was feeling anger or frustration or even just downright hatred, I wanted to know, where do you go with that? And how do you express that? I pushed myself further and further into those areas. Although ultimately the divorce was the impetus for the record, if you like, in terms of its content, I think it also goes beyond that. And I’m glad that people didn’t know too much about the divorce happening at the time the album was released, because I didn’t want it just to be seen in that light. I think it’s got more to offer than that.

Pitchfork: Has she heard it?

Sylvian: She heard it when it was completed, yeah. It was very painful for her to listen to. There’s no way around it. It wasn’t my intention to give voice to something that was very private and make it very public.

She thinks it’s the most powerful record I ever made. She’s very generous that she can hear that.

Pitchfork: And the album doesn’t have a resolution, though the end’s more upbeat.

Sylvian: Yeah, the end is– it’s more like a longing, a yearning, a hope, rather than a clear indication that everything’s resolved satisfactorily.

Pitchfork: When you were making it, did you feel isolated by your location? And was that good or bad?

Sylvian: Definitely good and bad. There were times when I felt painfully alone. I have no community of friends in this part of the country. Every friendship I have outside of my children is long distance. So if I’m here for any length of time, the sense of isolation can be overwhelming and really overbearing.

At other times, when I’ve been traveling and been away for a while and spend time with people, returning here can seem like a real retreat in the positive sense of the word. And I can get work done with no distractions. I can spend time with my children. I’m in that proximity where we can still be, although an estranged family, a family.

Pitchfork: So your ex-wife lives there too?

Sylvian: Yes, we’ve divided the home, and it’s a bit of an experiment to see how that works. But I now think its possible that we can make this work for a few years, to make the ultimate break a little smoother, and easier on the kids as best we can.

Pitchfork: Do you spend time in Peterborough [the nearest town to his home]?

Sylvian: I just don’t– I thought of moving to New Hampshire as a retreat anyway. We were following a very spiritual path. It was previously an ashram, so it had all that energy about it. And I didn’t feel the intensity of the solitude. I sort of reveled in it for a number of years.

But when the marriage began to fall apart, there was no companionship, no mutual goal or shared vision. And we went our separate ways in that respect. And so I began to lose track of my practice and my discipline that was holding me together in that place. I’m certain I will return to that practice, and that discipline. I had to go through a rather complex journey to find myself back at the same place, where I can take the reins of my own life and really bring myself forward and set my own goals. Before, everything was centered around the family and work. Now the family’s dissipated.

I still find it difficult to get my head around that fact. Not that I’m yearning for it to be put back into place– it’s impossible to do that– but I wanted to be able to have as much of a natural environment for my children as humanly possible. But at the same time, I know I have certain needs that are going to take me far and wide away from that. And I’m still trying to find a balance in all of that– how much do I need to be away from them to feel complete in myself, that I can go on giving to them.

So that’s kind of where I find myself, just trying to maintain or create that kind of balance which has been absent for the past two years or so.

/ / /

Pitchfork: On Blemish, the vocals are front and center, but in other ways they’re confined by what the music’s doing. I also noticed that that might have been the first album where you really chopped up and distorted your own voice unnaturally.

Sylvian: That’s the first time I chopped it up in that fashion, I had obviously treated it in different ways before. I mixed the vocals extremely loudly. It’s very much up front, and when I played it back in my home, the voice took on almost a physical presence. And that was very interesting to me. It was almost confrontational. It was like this entity that was in the room, with me, having this dialogue with me, and I’d never had that experience with a recorded piece of music before. And maybe that’s something I’d like to explore further.

Pitchfork: You’ve also had a number of influences from ambient music. Do you think Blemish helped to combine your ambient and song-based work?

Sylvian: I guess so. There were precursors to Blemish. There were little signposts that you can point to and say, “Well, that obviously leads to this.” I don’t know, I saw the instrumental material over the years as being something like a microcosm of one of the pop songs. If you took an aspect of a track like “Before the Bullfight” and just took two seconds and extended it, you may end up with Plight and Premonition.

And so it’s not such a strange idea to begin to explode the notion of the composition and draw it out. I mean Blemish was predominantly drone-based pieces. You’re working along similar lines as something like Plight and Premonition. It was just a means of entering into that material but retaining the forceful character standing within the landscape instead of removing him [from it].

I think it was important to do away with the given structure of popular music for that album, and in a way that’s where I want to continue to move. Because I’m finding that the given forms of pop music have begun to lose their currency. Maybe they lost it a long time ago and there’s just occasionally one or two very gifted writers that can just put everything back into that form, and really [do it] in such a beautiful way that it still has relevance. But even if I’m going back to artists that I’ve enjoyed for many years, decades, and listening to their work, I feel dissatisfied with the form. It almost feels as if it’s outlived its time, that we need to find new ways of talking about the same thing. And in a sense I tried to do that with “Ghosts” many years ago. That was what was being aimed at. The form was still there; it was just disguised.

Pitchfork: There is a lot of pop music that’s going in the same kind of direction, of stripping away the choruses or the melodies. Are you interested in much recent music?

Sylvian: Missy Elliott is really creative in what she does, with structure. I think it’s beautiful. If you’ve got a groove, it underpins everything, and it helps anything else you want to throw on top go across pretty smoothly, pretty easily. The four bar beat is very forgiving. [Laughs].

In terms of contemporary popular music, I guess I don’t listen to a lot. And I wish I listened to more. I guess I just don’t find enough that draws me back again and again. I listen to a little bit of world music right now, but most of my listening has been coming from that ground which is yet to be defined, which is where improvisation and jazz meets contemporary classical meets contemporary vocal music. There’s a lot going on in there, and I love the fact that it’s ill-defined and that there’s this enormous amount of crossover, and there’s a sense of possibility there.

I’ve worked with some of these people already on my next solo project, which I started about a year ago. I’ve worked further with Christian Fennesz, and a collective of musicians out of Vienna, and Keith Rowe and a few other people. So we’re seeing how that is going to develop.

Pitchfork: Going back even to your first albums, were there any specific artists who influenced your music?

Sylvian: Brian Eno’s early work certainly influenced [Japan] and me. We grew up listening to his music as teenagers, so Another Green World was a very important album for all of us, it was an incredible work– still is– and related artists, like Jon Hassell.

But a lot of the development of personal vision just came out of working. You just keep at it for a while. God, I made so many mistakes with the band, and you really learn from those and begin to understand what the strengths and weaknesses of the material are, and what are those areas that you really enjoy working on. When you write a song, it’s a song until you get into the rehearsal room and you begin to expand upon it, and then you get into the studio and you get into the details. The orchestration of the piece.

The details are what always interested me. And so I just began to spend more and more time on those details, until they came to the forefront of the material– textures and atmospherics. I began to elaborate on those more and more and push the rhythmic element a little bit further back. I was never that comfortable writing more driving songs, more driven material. Which always pissed the group off, especially Steve and Mick. “Jesus Christ, another midtempo beat!” Or a downtempo beat! [Laughs]. There’s always this pressure to write more in a certain vein. But then when I wrote “Ghosts”, I thought, “This interests me more.” As much as I like a good groove– performing live, it’s great to have a good groove– this really did interest me, and that’s when it became apparent that this isn’t a road I want to travel with the band, this is a road I want to travel alone.

I think that’s what happened– the material evolved. It evolves the more you work on it, the more you develop your vocabulary. You assimilate the influences, they become a part of your vocabulary, whether it’s musical influences, literary, whether it’s life experiences, cultural experiences– somehow ultimately God willing they all become part of your own vocabulary.

For me, I think I’ve been very slow to develop that. Because I started very young, and very insecure, so I would hide behind personas and all the rest of it. And I was very slow to find my own voice. But during that process I was learning how to write, how to find my voice, and how to write effectively for groups of musicians.

And of course by that time I had the success in the band that afforded me the luxury of being able to do that, and have a major label support it.

Pitchfork: You seem to spend a great deal of time on most of your recordings.

Sylvian: Back to Brilliant Trees, most of the time I was working one-on-one with each musician. Occasionally I’ve had the rhythm section working together, and we’d put down a groove, and I’d build from there. But often times, I’d just be working with Steve recording the kit piecemeal– you know, we’d take the bass drum, or we’d take the snare, and then we’d do the hi-hat, and we would just build up the track in that fashion. And then we could work on the sonic nature of the composition as well as the construction itself.

So yeah, I’ve always in a sense worked in a very piecemeal way in the recording studio. I enjoy working alone, being able to make all those creative decisions. I’ve done a lot of collaborative work over the years, and there’s an awful lot of compromise involved. And some of it’s creative, and a lot of it isn’t. You could see something you thought was very powerful being watered down and diminished in some way, just because you’ve got to come to some mutual agreement.

/ / /

Pitchfork: You often write about your spirituality, and your practice, in your music. I’m just a layman, but I wanted to ask, where you are with it today?

Sylvian: It’s a very difficult question to answer, because I don’t ever think of it as a linear journey. And when you think you’ve fallen off the wagon and you’re not keeping up the practice, you think you’re moving away from what is spiritual– [but] not if you view life as a series of lessons that bring [self-]realization. I couldn’t have created an album like Blemish [without] a part of me that could step back and view it objectively and say, “You’re going through hell right now. But that’s very interesting, isn’t it?” [Laughs]

I really respect that level of comprehension, and just being able to have that control where it’s possible to retain even that modicum of objectivity. And I’ve always managed to retain that, over the past five years or so, since the practice has afforded me that luxury. So no matter where I find myself, no matter how far off the track I seem to be, there’s still that part of me that’s objectively saying, “But that’s really interesting. I wonder where that will lead you, and how are you grappling with the different complexities that are entering into your life, philosophically, emotionally, intellectually, on all different levels. You’re being tested. You’re not the person you think you are, that self-image that we try to hold onto is falling away.” There are holes, and if you don’t recognize the holes in the picture, you’re not being true to yourself.

The process never stops– the process of self-analysis if you will, which is reinforced by the practice, or simple meditation, for want of a better word.

But there really is no loss. There is no linear journey. People talk about a spiritual path, but to me that would indicate that you know where you’re going and oh, we’re at this signpost, I’ve only got 30 miles– it’s not at all like that.

I like the Buddhist approach, that you’ve always been encouraged to question everything, to take nothing for granted. It’s the most scientifically friendly sort of religion there is in that respect. It’s a kind of science for the mind, as it’s been touted, and I think that’s the healthiest approach to all aspects in life. Nothing should be taken for granted. Everything should be questioned. There should be no stigma attached to the process of questioning, “What are you doing? You’re undermining the faith, the religion”– if it can’t withstand questioning, what value can it possibly have?

Pitchfork: But you also work with a guru. Are you able to question her?

Sylvian: There’s room for doubt, for questioning. Most of it’s internalized. I don’t have a relationship with a guru where I will go to that teacher and ask them specific questions. I can, but that’s not the way I choose to work. The notion of a guru to me is a physical representation of your higher self. So basically what you are surrendering to is your higher self.

If that’s true, then the whole dialogue is going on internally. It’s not an external dialogue. The guru acts as a provocation more often than not. Initially it’s a seductive, romantic relationship, and when you’re in the fold, it becomes provocative, it tests you. And I’ve never come across anything that is as pinpoint accurate as the message you get through the guru. You go through this process with other people who have common goals, you see them confronting their fears, the tests that they’re put through, and you look at the manner in which they’re tested and think, “I could handle that.” But when the opportunity for you to learn from your fears comes along, it’s like, “Jesus Christ, give me any other lesson you choose, but not that one.” It’s like laser-sharp accuracy, it’s right there on the nerve, and it’s like, “Shit, I don’t know if I’m ready for that.”

And it’s often like that, and you work through that, and it’s enormously painful. And if you manage to come out the other side of it, you sort of reach this plateau where you are somehow able to breathe really deeply and say, “Jesus, I’ve made it through that. Something I was so afraid of, that I didn’t think I could ever relinquish that fear in this lifetime, I’m sort of over it.” And you get this wonderful period where you’re able to just kind of soak in all that that means and all the benefits of that.

Before you hit the next one. [Laughs].

You get deeper and deeper, but then the highs get higher and higher. So that’s what impels you forward, I suppose.

Pitchfork: Your songs, all the way back to Brilliant Trees, are very romantic, but they could also be read as spiritual– “Wave” for example.

Sylvian: Oh, absolutely. That was the objective with those pieces. For me it was a spiritual romance. I thought, “Maybe this doesn’t really have a home in popular music, how do you deal with this?” But you can talk about it in the same terms as a physical romance– so that’s what I tried to do. I tried to open it up to be interpreted in different ways. Obviously most people saw it as a love song, to someone, and they used it in that capacity in their own lives, and that’s terrific. But the grandiosity of the romance of a piece like “Wave”, existed because it was about a divine love, a universal love.

/ / /

Pitchfork: When you recorded for Virgin in the 1980s and 90s, did you ever feel the need, or the temptation, to make commercial compromises? For example, did they ask for things like radio edits for Gone to Earth?

Sylvian: I wish there’d been a little more of that, because that would have indicated more interest on their part. [Laughs]. Simon Draper, who was the CEO of the company, was very supportive and would allow me to pursue any avenue I’d choose to pursue. But it didn’t always carry through the company– [the album] got to the marketing man, and you can just imagine the conversations that went on. “What are we going to do with this?” And ultimately they did very little with it.

It was always a struggle between knowing that I could do whatever I wanted to do and really valuing that freedom, and then knowing that there was a machine here that didn’t know how to channel it so it would find an audience. They had no idea. But I stayed because I had that creative freedom, and I had to get the word out myself by touring, by talking about it, whatever. –

Pitchfork: Would you have made compromises to get more support from Virgin?

Sylvian: You know, there are people who work in labels that just have to have a say about something, because otherwise they feel that they’re not doing their jobs. And they’re the people that you end up dealing with. They’ll present you with an edit of your material– “I edited this for you”– and the edits aren’t musical, they’re all in the wrong places.

I find it offensive that the materials were handed to me that way, and they would find it offensive that I refused it. No matter how kind and polite you are about the process, it doesn’t go anywhere unless you embrace the ideas of the people working at the company. And I’ve always found it very hard to do that.

If somebody’s selling you a compromise that would really benefit the work and will potentially get it a much larger audience, there’s no cynicism in that, because you make a work to communicate. You don’t just want to communicate with 10 people over there, you want to communicate with as many people as possible, as many people as the work might reach emotionally. Sometimes a little compromise isn’t a bad thing. You don’t need to be precious about it, but you do have to feel that the compromise is valid, that there’s a point to it, that it won’t change something about the nature of the work. And very rarely was it ever valid.

/ / /

Pitchfork: You’ve commented in the past about the political climate in America. Do you feel surrounded by it out here, or does it seem like a distant problem?

Sylvian: I have to cut off all media. I actually don’t indulge in listening to the radio. I don’t have television. When I do tap into what’s going on, I feel furious at what’s being done in the name of the American people, and the bullshit you have to swallow, being an American. I find it pretty hard going actually.

Pitchfork: You worked on World Citizen with Ryuichi Sakamoto. Did you write the lyrics? Sylvian: Yes. [Laughs]

Pitchfork: They were very direct.

Sylvian: The thing was, it wasn’t my natural inclination to get into writing protest songs. But it was a request from Ryuichi to give it a bash. And I felt that there was very little dissent being vocalized in the States. I thought, well, rather than putting something out that’s a little esoteric dig at what’s happening in the world right now, it just has to be straightforward. pPut the facts out there. Tell it like it is, because we want to make people think a little more about what’s going on.

Pitchfork: For the remix album for Blemish [The Good Son vs. The Only Daughter], you selected a very international set of artists.

Sylvian: I think of [Samadhi Sound] as being global, and not necessarily based in the States. It’s sort of stretched between the States, Europe, and Japan. I think nowadays it doesn’t really matter where we are physically located. We create our own culture around us to a large extent, whether it’s what we’re listening to, what we’re watching, what we’re reading– it can have very little to do with one’s immediate cultural environment. We are in a global culture in that respect.

I like to go where the most interesting ideas are being produced, and tap into that aspect of the culture, and explore that. Rather than the day-to-day mundanities of what it is to be living in northeastern America, or wherever.

Pitchfork: Do you use the internet a lot?

Sylvian: All the time. In fact, a lot of the work that I do is done via the internet. I have yet to sit in a room with Burnt Friedman [his collaborator on the new Nine Horses album, Snow Borne Sorrow] and play any music. I mean, we’ve sat in a bar together, and prior to that we were backstage at a gig in Cologne. We haven’t really engaged in some kind of musical conversation face-to-face. I’m fascinated by that: How organic a piece of music can sound and feel even though these musicians were never in the same space at the same time. And the technology really liberates you as a musician, as a producer, to create works that have that sense of an organic whole, even though they’re comprised of small entities, cut and pasted together.

It’s fascinating to work in either context. And I often find nowadays that more musicians are able to give more time and more concentration to the work if they’re working in isolation, than if they were working in the immediacy of an environment in which you have to have something completed within a short time frame. There’s something wonderful about that too, because there can be a terrific energy obviously– we create a tension that brings an exciting performance out of everybody. But we’re not so aware of the benefits of file haring. And I do think there’s a lot to be said for it. I do think there’s a lot of commitment that people bring to the table when they are left alone with this material. At least, that’s what I’m finding.

Often I’m working with people I’ve never had a conversation with outside of an e-mail exchange. And you’re just sending material off to the other side of the world, it comes back, it’s either absolutely perfect as it is or it just needs a little bit of shaping and reediting, and everything falls into place. Not to be too idealistic about it, but it is that sense of shared musical vocabulary.

/ / /

Pitchfork: You’ve said that The First Day tour in the early ’90s was one of the first times you enjoyed live performance.

Sylvian: That was because Robert [Fripp] gives an enormous amount of support on stage. He would come to the concert soundcheck, [and] he wouldn’t leave the theater, he’d be there all evening, he would be practicing in a certain form of meditation, if you like. And when we hit that stage, I could feel that energy coming. His focus was 100%. And I just respected that so much.

It was the trio work that we did first, only in Europe, Trey [Gunn], Robert and myself, that was the eyeopener. We had some material which was kind of knocked up one week before we went on the road, and so it was very unstable, and just sitting there on stage with these guys and just trying to keep a hold of it was fascinating. There were periods in the evening when I was doing nothing, and I was just absorbed in what Robert was doing. And I began to realize that is was a comfortable place to be. I enjoy this environment. Up until that point it was all about reproducing the songs and presenting them in such-and-such way. But this was different, and this began to interest me, and it opened up my eyes to the pleasures of performing.

The Blemish tour was slightly less enjoyable because there wasn’t enough flexibility involved in the performance of the material. A lot of it was laptop based, and so it didn’t have that unknown element to it. And it was just Steve and I performing, so we kind of knew what we were doing.

Pitchfork: Do you have any future tour plans?

Sylvian: I don’t. With every tour that I’ve done over the years, I’ve told myself it was the last. The only way I could get through them is to say, “This has to be the last one I’m going to do.” And then after a period of a year I think, “Well, maybe we could do that one more time.” But I have reached a point where I could stop, for sure.

I could imagine different scenarios where it could be very interesting to get back into live performance, if it wasn’t all about presenting the prerecorded material. The difficulty with that is presenting that idea to my audience. If I just come to improvise, I don’t know how well that’s going to go down. And I don’t know how the improvisation community of listeners is going to embrace me in that context either. But that’s something I think about.

Pitchfork: Have you considered any small venues or living room shows? [I bring up the non-event series in Boston, and the improv shows at the Zeitgeist Gallery in Cambridge, Mass.]

Sylvian: It could be very interesting.

It would depend on the expectations of the people who come to see the show. If they’re willing to settle into a different experience, I could imagine it being very fruitful and exciting for everybody.

Blemish and the remix album The Good Son vs. The Only Daughter are available now at www.samadhisound.com.

Sylvian’s latest project, Nine Horses, includes his brother Steve Jansen and electronica artist Burnt Friedman, with guest appearances by Ryuichi Sakamoto, Stina Nordenstam, and Supersilent’s Arve Henriksen. Their debut, Snow Borne Sorrow, was released October 10.