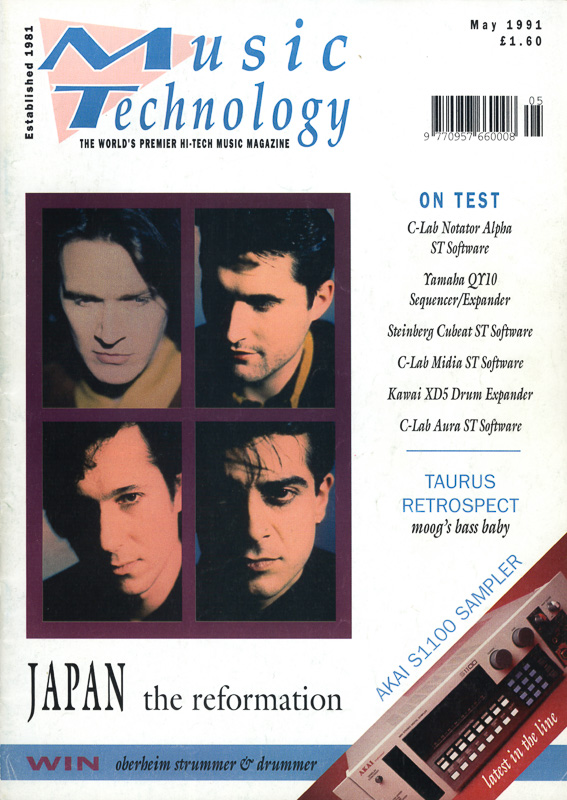

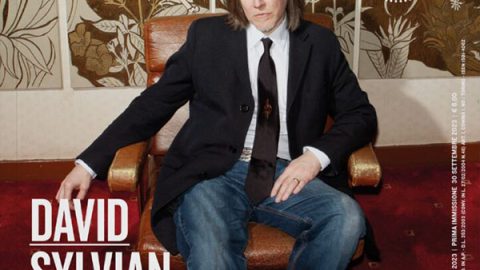

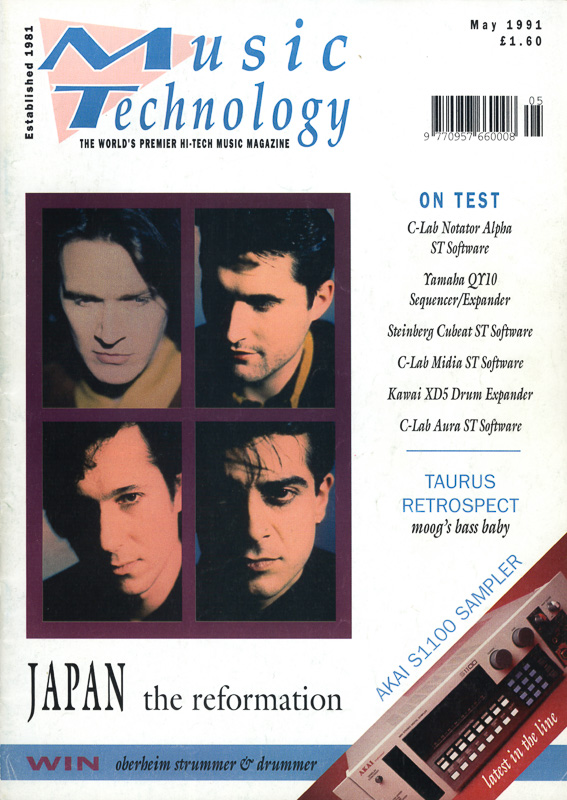

Exorcising Ghosts, David Sylvian by Tim Goodyer

The charismatic singer, composer and lyricist rejoins the former members of Japan for their first LP in ten years. Tim Goodyer talks technology, philosophy and improvisation with David Sylvian.

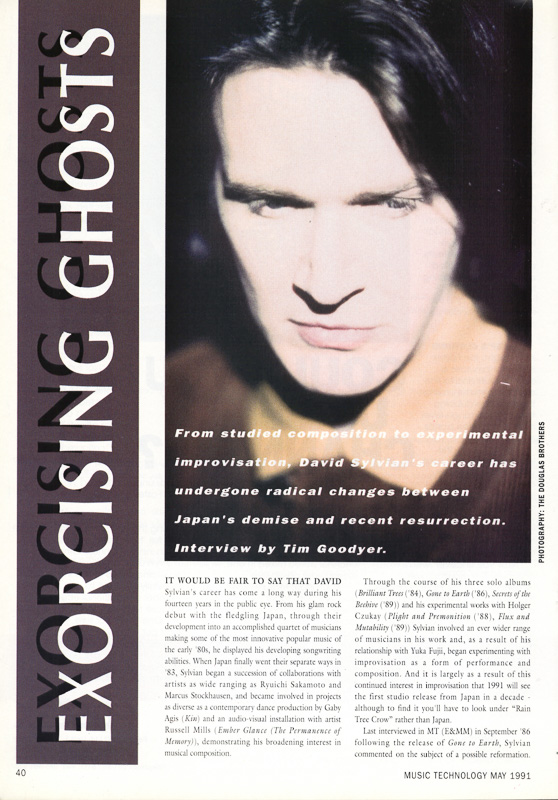

From studied composition to experimental improvisation, David Sylvian’s career has undergone radical changes between Japan’s demise and recent resurrection.

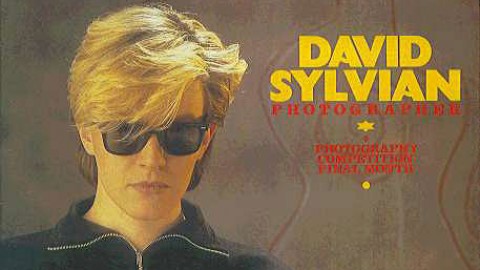

IT WOULD BE FAIR TO SAY THAT DAVID Sylvian’s career has come a long way during his fourteen years in the public eye. From his glam rock debut with the fledgling Japan, through their development into an accomplished quartet of musicians making some of the most innovative popular music of the early ’80s, he displayed his developing songwriting abilities. When Japan finally went their separate ways in ’83, Sylvian began a succession of collaborations with artists as wide ranging as Ryuichi Sakamoto and Marcus Stockhausen, and became involved in projects as diverse as a contemporary dance production by Gaby Agis (Kin) and an audio-visual installation with artist Russell Mills (Ember Glance (The Permanence of Memory)), demonstrating his broadening interest in musical composition.

Through the course of his three solo albums (Brilliant Trees (’84), Gone to Earth (’86), Secrets of the Beehive (’89)) and his experimental works with Holger Czukay (Plight and Premonition (’88), Flux and Mutability (’89)) Sylvian involved an ever wider range of musicians in his work and, as a result of his relationship with Yuka Fujii, began experimenting with improvisation as a form of performance and composition. And it is largely as a result of this continued interest in improvisation that 1991 will see the first studio release from Japan in a decade – although to find it you’ll have to look under “Rain Tree Crow” rather than Japan.

Last interviewed in MT (E&MM) in September ’86 following the release of Gone to Earth, Sylvian commented on the subject of a possible reformation. Then he regarded it as a romantic rather than practical idea, and admitted that it had been discussed on several occasions: “It almost came off’, he revealed, “but there wasn’t enough conviction and now I’m happy that it didn’t. I’m sure that it’ll be talked about again in another five years but I hope it’ll always be talk because I don’t think it would be a good thing.”

Curiously, it’s just four months short of the prescribed five years that I find myself face to face with David Sylvian once again. Dressed in a brown suit and sporting the long hair that has become the badge of “the artist” over generations, he is happy to talk about the reasons for his change of heart.

“It was mainly my interest in this method of composition: improvisation”, he begins. “I began to feel that there was possibly more to be gained at this moment in time by putting myself into situations where I would be forced to respond on the spur of the moment to what was happening in the studio or a given environment. That if I was to rely on my compositional techniques – as they eventually become, no matter how you try to evade these things – I might miss certain developments in my work, or that the developments might be rather too slow.

“I felt I was going through some inner changes which I found hard to encapsulate in my own songwriting, and I wanted to put myself in a situation where I would have to respond immediately without thinking about the situation to see what would surface. Then I could kind of glean an understanding of what was going on there and try to adapt that and develop it – whether this was along the lines of lyrical content or musical content.

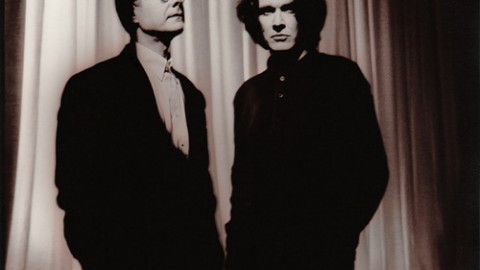

“I began to think that the idea of group composition would be a good thing to put myself through. I carried the idea of a conceptual band where the line-up changes from album to album about with me for quite some time, and I needed a testing ground. I needed to work with people I knew very well and who I thought would also benefit from the experience – so it was an obvious choice to turn to Mick, Steve and Rich. They responded really favourably to the idea and it worked in the way I expected it to.”

Could it have been that, after ten years of being solely responsible for the direction of his music Sylvian needed the security of a regular line-up of musicians to help him take the next step?

“I would say that the next step was so unclear”, he responds, “There were so many avenues I could walk down, that I thought the best thing to do was just jump in at the deep end, into a project I had no preconceived ideas about material-wise, content-wise to see what would happen. So it’s not so much helping a pre-conceived form of composition or content, it’s really to move away from having the room to think about what one wanted to do, and go ahead and put myself into a project where I had to go through with it no matter what happened. You take the first step and from that moment on, you’ve got to work through the whole process of making the album.”

The album in question – also entitled Rain Tree Crow – is unmistakably both David Sylvian and Japan. Gone are the carefully-ordered arrangements that characterised Japan’s last studio LP, Tin Drum, and gone are the obvious sonic references to the Far East. In their place are twelve more introspective pieces reminiscent of Sylvian’s solo works, along with the unmistakable styles of Richard Barbieri’s synthesiser programs and Steve Jansen’s drumming. Aside from the fresh approach to constructing the songs, the greatest departure from the old sound of Japan is the rationalisation of Mick Karn’s fluid bass playing.

More surprising is the fact that roughly half the pieces carry Sylvian’s distinctive vocal. Back in 1986 he had expressed reservations about his abilities as a singer to realise his musical goals. Instrumental works, he suggested, removed this obstacle from the working process.

“I guess I was most in favour of doing an instrumental album”, he concedes, “but often it would be mentioned that a vocal would suit a piece and we’d try a few ideas out. The problem lies in that there aren’t enough soloists in this particular band, and the vocals are a capable solo instrument as such. Otherwise we’d be constantly resorting to the same instruments over and over again, treating them and so on – which is what we did. We treated the saxophone in various ways, and the bass clarinet makes numerous appearances. We got a few guitarists in to compensate for my lack of ability. Basically we were trying to keep it all in the family rather than get too many people involved.”

Part of Sylvian’s readiness to provide vocal melodies relates to the success of the songs on Secrets of the Beehive.

“I was far happier with my performance on Beehive than anything I’d done previously. That album was far more lyrically based, therefore the emphasis was on the voice. The pieces were short and to the point; that was a different way of approaching the same problem, but the instrumental work is still very important. That’s the area in which I see the most potential for working within a group format – whichever that group may be. I find I know exactly what I’m doing when I write a song; I know where its value lies and how to develop that. I can do that with instrumental pieces, but I get far more satisfaction out of the give and take situation which exists within a group.”

Discussing the recording process with the other members of Rain Tree Crow, it quickly becomes apparent that each musician’s experience was unique, and that each has an individual perspective on the experience. The compositions were drawn from hours of improvisation which took place at a number of recording studios. It was therefore necessary to invest a large amount of work in editing, restructuring and, in some cases, re-recording the improvisations. It all began with a track called ‘Blackcrow Hit Shoe Shine City’…

“That was one of the most difficult pieces for me”, comments Sylvian. “It surfaced, I think, on the second day of recording and it was the only piece where the band were totally confident that a piece would work. On all the other pieces there was somebody who was a little unsure about whether it was working.

“I worked on this piece obsessively, trying to make some sense of the structure of it, but the band themselves found the piece complete as it was. I was working alone and also against everyone else because they weren’t really in favour of me taking it any further. The vocal went on at the very end because I was trying to avoid putting a vocal on it at all, then I got Bill (Nelson) in to play some guitar. Once I’d got Bill’s guitar on, it began to fall into shape. I could see there was a structure with the right dynamics to make it work for me, but there wasn’t a dynamic peak as such so I had to put the vocal on. I had the idea, but I had to get to that point where I recognised it was absolutely necessary.”

True to the traditional artistic stereotype, Sylvian’s satisfaction with any of his endeavours is balanced by his dissatisfaction over their shortcomings. Given that the project could not have come about without his full co-operation, and that he’s already on record as saying “One of the most important lessons I was reminded of was that being in overall control of a recording should rarely be relinquished. Group decisions are invariably of a compromised nature”, had the project been a success or a failure? His reply, however, is uncompromising.

“I am always disappointed in some respects with the work that I do. I always feel that it falls short of its original potential in some way, but maybe that’s what spurs me on to try again and again. What I tend to find is that, as much as I like some of the songs on the album, it’s the instrumental pieces that justify the album’s existence. It was on the instrumental that we really worked together as a four-piece. That was the aim of the project: to get the full potential from these four musicians working together in a really collaborative sense. I found that with the songs, I could see references to my own work far clearer than I can in the instrumental work, so I kind of feel that the emphasis should be placed on the instrumental work.

“‘New Moon at Red Deer Wallow’ I think is really exceptional. I feel the track realises the potential that this group always had that was never realised before. For me this is the first time, and maybe the last time it will be. And I’m happy; I don’t mind if it’s the last time because it’s there, and I’m very happy with that piece of music. If it was that piece of music alone that came out of these sessions I’d be happy. It would justify the recording process, it would justify this project.”

Sadly, however, the project seems unlikely to yield anything more than one album and the possibility of a single. The reasons for this are shrouded in personal politics within the group (see Steve Jansen’s comments elsewhere in this issue).

“It was always considered to be a one-off’, states Sylvian. “There was a slight possibility of a second album, but I don’t think it would work. The impetus wouldn’t be there, the enthusiasm for the project would’t be there, the flexibility wouldn’t be there… All the elements that made this album work – the kind of mental approach you take to a project like this – would be absent. There’d be too much anxiety and there’d be too many conflicts. I know now there’d be conflicts because of coming out this side of the album, so to speak. There are now disagreements about certain aspects of it, but that didn’t happen while we were making it, because there was so much enthusiasm going into making it. It’s a unique experience in that way. In ten years time, who knows? But it would be silly to do it again now.”

MOVING ON TO THE MORE PRACTICAL aspects of Sylvian’s music, his move towards improvisation has brought about various changes in his playing. Instead of spending time writing material, he now finds playing for his own pleasure a rewarding experience – though the predictable acoustic piano or electronic keyboard are not his chosen medium.

“Because of steering away from writing, I’ve found myself picking up instruments and, where my inclination in the past was to write immediately, I’ve started just to play. I’ve become a much better guitarist for a start. Some of the more adept solos on the album came from Bill (Nelson), Michael (Brook) or Phil Palmer, but I played all the other things.

“I really got into playing the Steinberger I bought on the last tour – influenced by (David) Torn’s playing – I find it so flexible. And I’ve just got into processing the sound and finding techniques to make up for my lack of technique. I’ve been finding ways of playing that I feel totally comfortable with which are maybe not what one would see as technically correct, but I enjoy approaching it… Putting myself into that situation with the group I really saw myself as a guitarist. That was the role I wanted to play: guitarist in a band rather than sitting up front with keyboards and a vocal mic.”

But sitting with keyboards and a vocal mic was a large part of Sylvian’s role. The keyboards in question were a Korg M1, Roland D50, “very occasionally” a Prophet VS and a Kurzweil 250. Of the Prophet VS he says: “I’ve had that for some time and I’ve been meaning to try it. It seemed to have a limited scope”. The Kurzweil, on the other hand, served to “supplement a few of the acoustic sounds”.

Most of the more recent advances in synthesiser technology, however, have failed to impress: “I find with later keyboards that they’re far too attuned to pop performance, pop composition, and so on. And they’re that much more inflexible because of it. Whereas the older synthesiser had a wider scope, you could buy one, use it for five to ten years without thinking of picking up another. These days you can run through the capabilities of a new synth fairly quickly and wear it rather thin over a period of months.”

His words have an uncomfortable ring of truth to them.

Another practical aspect of music is taking it to the people – which Sylvian did on his In Praise of Shamens tour in 1988. Accompanied by Jansen, Barbieri, guitarist David Torn, trumpet player Mark Isham, guitarist/keyboard player Robbie Aceto and bassist/percussionist Ian Maidman, Sylvian performed material from Brilliant Trees and Secrets of the Beehive. From the front of house, it looked like a finely-managed collective of musicians performing music of rare quality. From backstage, however, came stories of Sylvian’s dissatisfaction.

“Generally my disappointment came from being too muddled”, he offers in explanation. “The emphasis wasn’t on songs on that tour, I was trying to create an atmosphere in a hall, and I thought it was going to be relatively easy to do that because it was something I thought I knew how to do. Although it was successful to a certain extent, I thought there wasn’t enough dynamics, there wasn’t enough colour. Occasionally too much happened, it could have been pared down.

“Unfortunately there wasn’t enough time to mature musically throughout the tour. We did to a certain extent of course, but all the time there were technical problems and organisational problems, and to deal with that at the same time as knowing you’d got a performance that evening is hellishly difficult to go through.

“I tried to pick musicians who were potentially the most flexible – Mark could cover some of Jon Hassell’s work and Kenny Wheeler’s work as well as his own, and the same with David Torn. But there are limitations; maybe I was trying to cover too much and should have gone for something a little smaller in scale. My dilemma was that I needed enough people on stage to be able to build layers and textures – we had to have enough of a diversity of instruments to deal with that.”

Sylvian seems to find the experience of recording music a more valuable one than that of performing it.

“It is the recorded medium that is important in that it has the potential to reach so many people. The live performance is far more transient, obviously. But it’s a different kind of experience and maybe shouldn’t compare in any way. Let’s say that what I have got to date from live performance is nowhere near as profound as what I can take from recording and writing material. The only person I’ve found to agree with me on a certain approach to writing is Scott Walker in a comment he made to me: I mentioned something about recording an album being very difficult and very painful, and he said ‘that’s the way it should be, if it isn’t there’s something wrong’. That’s what I’ve always felt to be true, but a lot of people I’ve worked with don’t share that. It is important, because the actual process of writing and recording, although it is a by-product of your life’s experience, it itself becomes a life experience through the process of making it. It becomes part of your learning process. The process of making a record is normally very difficult; very challenging and emotional on all different kinds of levels, but by the time you complete a project it holds within it that experience. That emotional depth is captured in the work somehow. And that can be brought out through the excavations of the listener if they care to probe that deeply.

“There must be a meaning within the music. To me that’s very important and it’s very hard to get that kind of intensity in a live performance. I haven’t achieved it, maybe that’s why I want to go back and have another bash at it, because there must be something I’m missing, something in my approach, something in my self-conscious awareness of standing on a stage performing that I can’t lose. I can’t find a musical experience to take me above that and out of it. Occasionally it happens, occasionally something raises you above that intimidating feeling of standing in front of a lot of people performing, but a lot of the time I feel self-conscious of being there running through the motions of something – which I think is an awful thing to do.”

While all this might reasonably lead you to believe that Sylvian’s only “solo” live outing to date will also be his last, there’s more encouraging news.

“This idea of the composition and that this is going to tape and is permanent is something I feel I ought to get away from. I ought to somehow be more immersed in the event itself rather than removing myself in some sense and objectively analysing what’s going on as it happens. It’s a silly thing to do really, but it’s the way I work. It’s the way I’ve always worked, and it’s very hard to get out of the habit.

“I want to tour again, and I see myself touring possibly next year. I’ve got some projects to get through this year which will keep me in the studio, and I’m not sure when I will get around to doing an album – whether it’s my own album or this group concept album – but whichever it is, I will tour with it. The problem is that the recorded work always takes priority. If I have ideas for something, I desperately want to jump into it right away rather than go on the road.”

Returning the conversation to the progress of Sylvian’s career, I find that the sense of optimism that characterised our last conversation has been replaced by the sort of confusion that accompanied the dissolution of Japan.

“What happened to me after Beehive was that I thought I’d said something quite well, quite concisely, that I’d been trying to say for a long time. With the recognition of that fact all this other stuff came to the surface which I hadn’t dealt with, which was much heavier, much darker. And I’m now back in the position I was in prior to Brilliant Trees, where I’m immersed in some very heavy emotional baggage I’m carrying around with me. I’m struggling to find a way of expressing that at this moment in time. I need to let time pass, but I don’t want to sit around doing nothing so I’m putting myself in situations which may just trigger something off. When Riu (Sakamoto) asked me to write the lyrics for ‘Forbidden Colours’, something happened and I was off – that lyric helped me a great deal. So I’m just moving through different projects at the moment, allowing things to take their time. When the moment is right, when I see that it is possible for me to write about this thing that I’m experiencing, I’ll go ahead and do it.

“In the meantime I’m developing some of the other capacities that I knew I had, but that had always taken a back seat to the writing – such as guitar playing, engineering, producing. I feel far better at all these things than I was just four years ago. I feel as if I’d got halfway up a ladder and had to take a few steps back to reassess where I am and what’s happened to me before I could go any further. Or maybe I’ve reached a level and I’m wandering back and forth until I find the next ladder. That’s what it feels like.”

Perhaps most encouraging of all is Sylvian’s reaction to the suggestion that there might be an end to his involvement in making music, that at some point, he might feel he has said all he has to say. His response is not to recognise the question: “There can’t be an end in sight. It would be self-defeating to think that there was an end.”

The interview closes positively; for Sylvian there’s another interview and a career to attend to, for me there’s an album by a band called Rain Tree Crow which I really must play again…