by Dave Rimmer

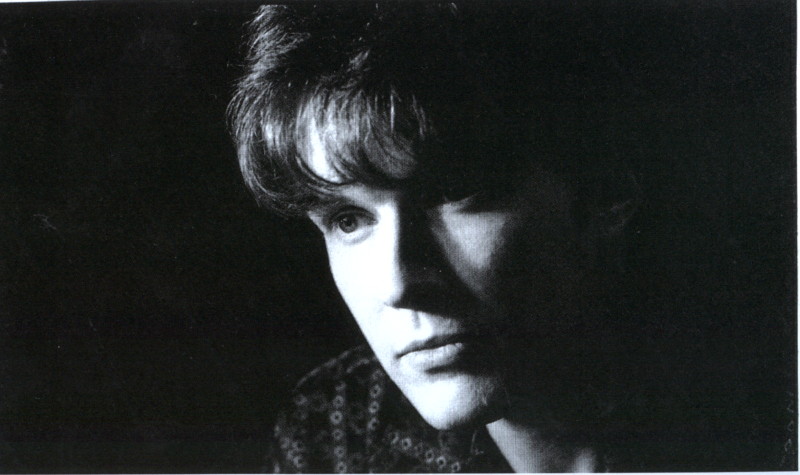

Having spent over five years behind a thick layer of make-up, David Sylvian has emerged from the cocoon of Pop Celebrity to make a butterfly foray into the avant-garde. His new work lies somewhere between wallpaper and revolution. But nobody seems quite sure.

The man who strolled into the lobby was small and neat, grey-suited with white shoes. His hair was a natural darkish-brown, a small silver crucifix dangled in the blood-red folds of his shirt. Owlish, tinted spectacles lent him a learned air while also obscuring most of his face. What remained visible was pale and clear. He smiled and said hello.

It was with something of a start that I realised this was David Sylvian. Indeed, such a transformation had he undergone from the willowy blond, heavily made up, with the fringe and the highlights, that I was unsure I would recognise him had he walked up in the street, sung a few bars of “Forbidden Colours” and begun taking Polaroids. Only the fact that he’d turned up in the right place (the Portobello Hotel in West London) at the right time (around four one Monday afternoon) properly clued me as to his identity, although the accompanying presence of his Japanese girlfriend Yuka Fujii helped give the game away.

“You look younger,” I told him, by which I really meant less grand.

“I thought I was looking older,” he smiled again, by which he meant more relaxed, happier having finally ditched the public image of the pop star of teen sensations Japan for the comfortable anonymity of the avant-garde. “It was like the opening of a door, to remove that superficial element that lies on top of the music….”

And even his voice seemed to sound different.

David Sylvian was always a reluctant participant in the circus of pop. Fed up with touring, disenchanted with entertainment and appalled by the effects of “fame, money, ego” on relationships within the group, he abandoned Japan around the beginning of 1983 – the every peak of their success. Sylvian at that point could probably compromised a little and become one of the more successful stars on the planet. But he was no longer interested in performing a precarious public balancing act. “I don’t feel equipped to cope with a teen pop image anymore,” he explains to confused but adoring young female fans, and set off to try and be “true to himself”.

Since then he has hoisted himself into that small but select group of artists who have managed to detach and distance themselves from commercial beginnings and pace out their own territories in splendid isolation. Where once Japan jostled with Duran or the Human League, Sylvian now rubs conceptual shoulders with the likes of Brian Eno, Peter Gabriel, Robert Fripp, Holger Czukay and Kate Bush.

Visiting an exhibition in 1982, Sylvian had been moved by a Frank Auerbach canvas as he’d never been moved by a painting before. “It hit me in the same way music does … inside. There seemed to be a moment of inspiration between the painter and the canvas that you could see, a direct line running through it.”

The painting in question, Head of J. Y.M. II, ended up on the sleeve of ‘Oil On Canvas’, the live album compiled from Japan’s final tour. Meanwhile Sylvian addressed himself to the problem of capturing this newly-discovered sense of immediacy in his music.

Technically no brilliant musician, he couldn’t even resort to the spontaneity of jazz. Instead he carried on composing his own pieces, but left spaces and invited some of his favourite musicians to come in and “compose over the top of them”. It turned into a sort of trilateral project, co-produced by Steve Nye and variously involving the talents of: American funk players Wayne Braithewaite and Ronny Drayton; renaissance man Ryuichi Sakamoto from Japan; and experimentalists from the European tradition like trumpeter Jon Hassell and former Can bass player Holger Czukay, these days to be found playing an old IBM Dictaphone he salvaged from the rubbish outside a Cologne office block.

The result was “Brilliant Trees”. You could take it as wallpaper music, or as a collection of songs. You could read it as an exploration of faith, hear it as an unsettling evocation of some nether spirit world. You could dance to bits of it … just. You could dismiss it, as the NME recently dismissed Sylvian’s recent “Words With The Shaman” EP, as “music to burn joss-sticks to”. You could describe it, as did our own David Toop (accurately enough) as “music in stasis invested with an emotional content frequently absent from minimalism.” You could admire it, with naked admiration, as one of the finest and most original LPs of 1984. So eagerly did it seep into my life that now I can’t even -think- (let alone write) about it without remembering, for example, a bittersweet mood of nostalgic melancholy I wallowed in enjoyably on a visit to the anguished bedroom of my adolescence. Perhaps it was a bit pretentious. But if you never stick your neck out, what are you ever going to see?

“If you think of the avant-garde as the bottom of the ladder and pop as the top, then I tend to work,” Sylvian laughs, “somewhere around the middle.”

Perched, back straight, smoking Disques Bleu on the edge of the bed, he really did look utterly different. Deeper than a “change of image”, it was something about his whole demeanour. No longer even a hint of the former space cadet, high on the thin air of pop celebrity, about the fellow.

“I don’t think I could work completely within the avant-garde because most of them are extremely proficient musicians and,” another laugh, ” I’m not.”

And, I keep musing, what if this isn’t David Sylvian after all? Maybe its a hoax. Maybe this is a bloke who looks a bit like him, employed to impersonate Sylvian for reasons as yet unclear.

“Because I have no technique as a musician, I tend to rely totally on the emotional content. But both pop and the avant-garde tend to suffer from a lack of emotional content — that is fundamentally my biggest criticism. ”

No make up, no platinum blonde hair ….

The thing is, Sylvian always seemed so comitted to make up. A fondness for the stuff was said to be the reason the four members of Japan all ended up hanging around together at the secondary school in Lewisham. It was one of the bigger sticks the music press used to beat them with from the appearance of their first, uncomfortable album in 1977. It was what made them suddenly fashionable in the naive flush of New Romanticism.

“Some artists spend ten or 20 years developing a single idea. That work has to be done. But its just as important that people learn from it and put it in a more emotionally-based area…”

And they still continued putting it on every morning, even though it was all interviewers ever wanted to talk about when really the group would much rather been talking about their music.

“I try to use the best of both worlds: the excitement and delicacy of pop as well as the lyrical content and bravado of the avant-garde….”

And when ‘Brilliant Trees’ came out, the solo Sylvian still looked the same. Blond hair. Fringe. Make-up.In 1984, Sylvian had an exhibition of his own. It was of Polaroids, collaged in a manner that resembled Hockney’s simultaneous “Cameraworks”, though less precise and often with pastels added. The work appeared in a book Perspectives. It was dedicated to the modern musician’s pet artist, Jean Cocteau (whose voice can be heard muttering in the background of some of the new material). And it was arranged geographically, showing Sylvian’s continuing preoccupation with travel: recording in Berlin and London (still his home), visiting France, India, Nepal and Japan with Yuka, his girlfriend.

In the autumn of ’84 the exhibition was in Tokyo -always a home-from-home since Japan’s first LP plunged them into abrupt Eastern stardom. Sylvian was approached by a TV company to make a documentary about himself. “The idea didn’t appeal to me particularly but I was extremely short of money.” (His records never make any, it seems, because Sylvian works so slowly – “Brilliant Trees” cost 100,000). So he did it, but “stretched the idea” to include sections of music and imagery. It was all made in a rush, but Sylvian liked one part, which became “Steel Cathedrals”: images of industrial buildings around Tokyo, shimmering and heaving with life, accompanied by a Sylvian/Sakamoto improvisation and all done in 48 hours. So he brought that back to London with him and began reworking the music.

He wanted to release it as a video, but felt he should record some more music to give Virgin the possibility of releasing an LP. That led to “Words With The Shaman” – originally one long work but cut into three because it had “begun to over-reach itself … it sounded too much of a grand statement.” Now unhappy with the idea of an instrumental LP, he suggested putting a vocal side with the “Steel Cathedrals” sound-track and began working on new songs, but they didn’t seem to work either. So while also contributing to both Czukay’s and former Japan bass-player Mick Karn’s new albums, he’s also continuing to work on the new songs with Robert Fripp, Bill Nelson, Steve Jansen and probably Kenny Wheeler for a follow up to “Brilliant Trees” that should appear sometime late summer.

“And originally all I wanted to do,” he sighs, lighting another Disque Bleu, “was release “Steel Cathedrals” as a video.”

Virgin Video didn’t want anything to do with it, had no idea of how to market a 20 minute ‘ambient video’ next to all the usual hit promo compilations, so Virgin records released it instead. Sylvian was grateful. “The best they can get out of it is a reputation for releasing more interesting videos.” And interesting it was. A relief from the manic, jumpy, attention-grabbing pace of most pop-promos, “Steel Cathedrals” can be watched intently or just left on in the corner and glanced at from time to time.

“I didn’t originally set out to do anything but create visuals that worked the same way as music does, in that they don’t dictate to the viewer but allow a starting point for the imagination. They could spark off something in the viewer’s … memory? It could be to do with colours, anything. Even if it bores them into thinking about something else …”

“Words With the Shaman”, meanwhile, surfaced as an EP, and a cassette, ” Alchemy – An Index of Possibilities”, was released containing the music from both that and the video.

“It has been quite a frustrating year. Just overcoming obstacles. It wasn’t very satisfying to be honest. And I’m very aware that the things I’ve done this year were for a very, very limited audience.”

“Words With the Shaman”, “Alchemy”, “Cathedrals”, and a new track titled “New saints and Sheep”…

“Religion is a very important thing for me – to find out what and why and give my life a positive direction. So often you sense what you’re doing is right, but I want to know what I’m doing is right … in a universal sense.”

Sylvian is serious but not sanctimonious about this. His intention is not to preach. Meanwhile, exploring his faith has replaced his old need to explore the world. Inspiration no longer comes from travel.

“I want to develop a spiritual side of myself because I believe that is the only thing in my life. What I’m learning about, it can’t help but appear in my work.

“I’m at a stage where I have to make a decision about which doctrine to follow and I haven’t made it yet. It’s not something I should talk about until I’ve made that decision.”

So we talked instead about my favourite of the new, unreleased tracks – “Laughter And Forgetting”, obliquely inspired by Milan Kundera’s novel.

“‘Laughter’ isn’t a reference to outright laughter, but to an enjoyment of life in its most noble sense. Not your life, but life in itself.

“‘Forgetting’ means … not to take things too seriously. Not to take yourself too seriously. To dig behind … to move away from a past or segments of a past you find it difficult to move away from – but in a positive way,” he sighs again. “That’s the best explanation I can give, but it has many more levels than that. ”

Which may go some way towards explaining what happened to the make up.