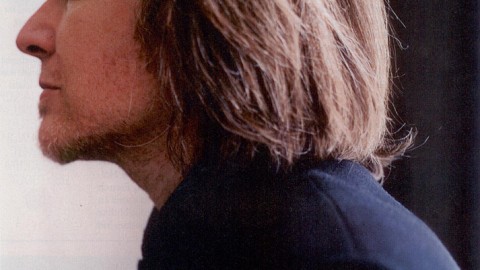

“DAVID SYLVIAN: WITH PURPOSE”

A conversation with a former Japan member, solo artist and life enthusiast, this eloquent englishman speaks about Rain Tree Crow, his solo work, life and his role in it all.

By Kathleen Galgano

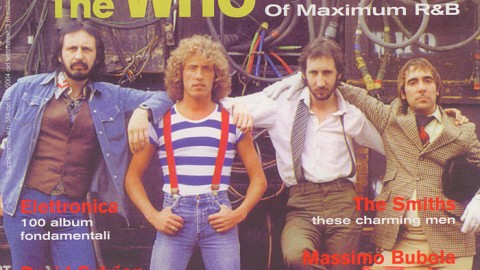

The late seventies’-early eighties’ brought forth David Sylvian out of the mysterious, avant garde, dance group Japan. Since the breakup of Japan, Sylvian has shed his pop-star image, left his tabloid days behind and taken a more committed approach to the effects of his writing. Already with thirteen solo record releases, his own five-cd box set collection, numerous collaboration releases and three publications under his belt, he has entered into another consortium, named Rain Tree Crow, with his former bandmates, Steve Jansen, Mick Karn and Richard Barbieri. This reunion led me to the privilege of interviewing one of the most fascinating — and interestingly easygoing — gentlemen in music today.

David Sylvian has undergone some radical changes in his beliefs and style of composing and arranging since his first achievements in the music world forefront. Now, rather than an entertainer, Sylvian probably would prefer to be known as a creator, an artist with a purpose, possibly even a teacher with his music being understood as a tool.

“Obviously, the work itself comes from personal experience, but to create work is to communicate. The work must have a function in society, otherwise there is no point in the act of creation itself. And what I try to do with the work, through the method I use in writing music, is to enable the listener to look within themselves,” explained David Sylvian.

With intricate compositions and alluring arrangements, his music is able to communicate feelings directly to some part of the listener’s intuitive side, escaping the mind’s normal comprehension. Such careful intentions have made Sylvian’s music some of the most thought provoking and emotionally stimulating collections of our time.

“Let’s say first of all, if we take entertainment in general, the listener or the viewer is encouraged to project away from themselves. Entertainment is valuable, but we live in societies that are unbalanced in that respect. We don’t have enough works that helps us to focus in upon ourselves, and the work that I do tends to do that, or at least it aims to do that, to enable the listener to look within themselves and find that space within themselves where they can begin to ask questions of themselves.”

“The process of questioning is the first steps to achieving levels of self-awareness, of consciousness, which I think is very important. It’s possible that art — in it’s greatest sense, at it’s most successful — can set parameters around the quality of those questions. So I think that art in general, you can say, is humanity’s way of sensitizing itself. It’s part of a healing process to effect one person. To act as a catalyst to a growing self-awareness, to a developing consciousness — is to bring that person into a state of mind on their own grounds, so it’s sustainable. It grows from within the individual themselves, and not something that is foisted upon them. By doing that, by changing one person or assisting in the changing of one person in a very positive way, you begin to effect society, and I think that is the basic level upon which art works and that is a very positive aspect of the healing that can take place in society itself.”

The Rain Tree Crow project was a way for David to experiment some improvisational recording methods, the results of which have proven to be, through sound, a passionately confident success.

“I was working with a friend of mine, Holger Czukay, on a couple of projects, and the way that Holger works is based around the idea of improvisation. It’s a method of working that he got from working within the group Can many years ago, and has continued to work in that way. But it was quite new for me to work in that manner — you go into a studio with no preconceived ideas and you just improvise material onto tape and then work with that given, develop that composition and put it into some kind of shape at a later stage. And after making two albums with Holger, I felt that the possibility of working with larger groups of musicians was quite exciting with this same concept. I began to think about forming some kind of conceptual band, where from project to project, the line-up of musicians would change, but the basic concept would remain the same. And I felt I would like to test the ground a little first, because I wasn’t sure how I would respond in that environment, how in-control I could remain of the musical direction, without inhibiting other musicians’ involvement, and so on. I just wanted, really, to see the pitfalls and the positive side of working in this manner, but in a relaxed atmosphere. So I began to think about working with the guys in the band again, and I posed the idea to them and they responded very positively. I felt there was a lot to be caught out of these individuals as performers. I knew their capabilities, and I knew that they hadn’t really been explored to any great extent over the past few years. I felt, as I knew them very well, I knew where to focus upon them to bring these performances out, so that was a challenge to me on a number of levels, really.”

It has been eight years since the four Japan members have worked together on an album, and the reunification had raised questions to whether maturity has effected the compatibility of these men in the framework of this new style of writing and arranging.

“We actually have very different reasons for making music. We don’t share common philosophy or anything like that. Fortunately, it didn’t cause conflict while we were working on the album. The level of commitment is the same regardless of the philosophy. It’s interesting to see friends in their environment, to see how they respond, to see how they’ve grown or not grown. I mean, there are times that we felt that nothing had changed, that we were there and we were responding to one another in much the same way that we did before. This isn’t to say that we haven’t change outside of those relationships, but once those relationships connected again there is a chemistry that comes about which is both positive and negative.”

“I guess there was a slight nervousness about it being a kind of regressive step to take, but I was quite confident in myself that because my basic motivation for making music had changed so radically between the time Japan broke-up and the time I started my own work, I knew that the content of the work would be different. I spent some time with the guys, before we went into the studio, to get to know one another again. I hadn’t been that social with them over the past few years, although I’d seen them on and off and worked with them occasionally. The three of them are very tight, you know. They’ve spent a lot of time together over the past eight years. But I needed to spend time with them and find out where they were at, what they were thinking about, and so on, and to inject some of my ideas into their world and see how they responded — before we got into the studio. This is without talking about musical direction or anything. We didn’t talk about musical direction prior to getting into the studio and playing. I really wasn’t worried about other people’s reaction to it on that level. What was important was that something essential should come out of this relationship, and something unique to this relationship that justified us working together again.”

“I think that the solo work is far more personal and far more potent, but I think that the work I did with the band is maybe far more accessible. To some degree, there’s a sense of going back over ground that you’ve already covered, which you would never think of doing in your own work. But in that context, because you’re improvising, you often refer to givens, your own techniques or whatever, come back into play on the spur of the moment, and you know they work because they’ve worked before in the past. It’s something you tend to avoid doing when you’re doing solo work but in this kind of improvisational arena you tend to throw in everything you possibly can to make a piece of music work. Therefore, there is a certain sense of confidence knowing that a certain thing does work in it’s way because you know you’ve done it before, but it’s in a different context and other musicians respond to it in a different way, so it comes alive in a different way. That’s quite interesting to work in that fashion.”

Sylvian explained that the curious moniker for the Rain Tree Crow endeavor was brought upon from the original idea of one of the songs on the album of the same name.

“The piece itself was dealing with the idea that if one is going through a rather negative emotional state of mind or experience in life, that the act of consciousness, the act of recognizing the fact that you are, is bringing light itself into darkness — the idea that light through consciousness enters into the dark negative state and the process of doing so creates the whole potential for healing, for coming out of that state into the light again. And it was using as a metaphor, the idea of Taiwanese Shadow Puppet Theater, that to see shadow you need the background of light, that light exists in darkness, is simply what it was about, basically. The image of the Crow was extended from that piece of music throughout the album and in different forms and became a personal symbol for me for a rather negative experience I was having at that time, and still am to some degree. It enabled me, through being able to objectify the experience in some way, by using this symbol, to understand what was happening to me, and therefore, the work becomes part of the healing process.”

Rain Tree Crow was recorded in eight different studios throughout Europe, an unconventional process which Sylvian attributes to the spawning of an amiable atmosphere for the work to ensue.

“When I recorded Brilliant Trees, I started the album in Berlin, out of necessity, out of a low budget and it being the cheapest studio I could find, but I found that going to a strange place, meeting in a strange place — all these musician for the first time, some of them I’d never even spoken to prior to meeting them — created a sense of adventure about the whole project, which I didn’t just feel it, I noticed it in the other musicians, and that they would give more of themselves in that environment rather than in their natural environment, their home town or whatever. So I began to try to manufacture that on projects I’ve done since. [Secrets of the] Beehive, I started in the South of France for the same reason, setting a wonderful location in vineyards and natural springs, and all these kinds of things, beautiful location to be in, very isolated and people feel very good about being there. And because they feel good, they give more. They feel more involved in the work, and they’re more open as people to work with. And so I’ve tried to keep doing that with the worked that I’m involved in, and so consequentially with Rain Tree Crow, because it was important that we feel relaxed, because we had no material when we went in, and there’s a lot of internal pressure you can put upon yourself under those conditions, it was necessary that it really felt good, felt relaxed. So I went back to the same studio that I recorded Beehive in for the initial stages of the recording the album. At the end of every month we moved to another studio and set up there. That was quite important, especially the early stages, the recording in South of France and recording in Italy. I think it was very important that we should be in a location that was conducive to writing, because studios tend to be very sterile places to work in.”

Another one of David Sylvian’s trademarks happens to be his highly selective choice of musicians for which to work with on his projects. He has worked with the best, including Holger Czukay, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp, David Torn, Phil Palmer, and Mark Isham, all of whose styles of performing compliment Sylvian’s creations exquisitely. Does Sylvian completely compose and arrange the music before recording, or does he allow these expressive musicians some free rein in the studio?

“It depends on the material and it depends on the musician. Let’s talk about Beehive…I had a very clear idea what I wanted with Beehive and I arranged the pieces myself, and gave the musicians involved a little freedom, but not so much, not so much as I’d incorporated musicians on Gone To Earth and Brilliant Trees, for example. I knew what I wanted. I knew what I was looking for. And so I chose the musicians very carefully that I knew would be able to work in that context and really give me what I needed. I’d worked with most of the musicians before, and particularly with Ryuichi Sakamoto, who I knew to be a good arranger and wanted to work with him in that capacity for some time. He’s a very honest arranger. I mean, I gave him my demos, and he would pick up my orchestral ideas on the demos that I had done and be very true to them, whereas another arranger would try and inject too much of themselves into it to make it more personal for themselves to be involved. And Ryuichi’s very good like that. He has a fantastic grasp of many different forms of music. He immediately latches onto what you want and what you need and tries to stay as true to your original ideas as possible. So in that context, that’s the way that Beehive worked.”

“With Brilliant Trees it was the other way around. I had very sketchy ideas for songs and pieces, and I went into the studio and allowed musicians quite a greater degree of freedom. It would depend on the performance…I may record five or six takes of a solo by an individual, and when they’ve gone, I would cut up the performance, select the best pieces of the performance from five or six different takes, and put them together. If they played in a certain eight-bar section, I may have shifted it to a later stage in the song or whatever. It’s manipulating material to your own ends, really. It’s using a basic live performance, a really strong improvised performance — a committed performance — to your own needs. And in a lot of cases, obviously, the musicians didn’t need any manipulating. They gave wonderful performances and perfectly placed in the pieces. It just depends.”

The deviation of Sylvian’s music from conventional standards does lead one into the inquisitive state that he has referred to. He realizes that sometimes people don’t understand his music or approach and that, although he tries to set the stage for a listener’s own self-work, occasionally he must define his objectives for this purpose and for his own accountability.

“I don’t mind explaining, in fact, I quite enjoy explaining the work. It’s a challenge to me. I have to justify why I do what I do. I have to justify it to myself, and it’s o.k. for me to sit on my own and justify it, but to be challenged is quite interesting. And if somebody asks me a questions which I can’t honestly answer, even to myself, then that’s a new door for me. That’s something else to unlock within myself. I care about the work that I do enormously, and I care about it’s effect on people, the kind of effect, whether I’m being successful or not, and unless I’m in contact with people that experience the work, I’m never really going to find out whether it is working or not. I’ve only myself…well, I say only myself, but I guess that’s the basic level of judgment it comes down to, to a level of recognizing in oneself if one has achieved something or not. But it’s important to me to know that people are responding to it and if I have to find different ways of expressing what I think is important through the work or not.”

“The idea, really, is that you’re creating a piece of music that comes from an emotional standpoint. That piece of music has to, when it’s completed, mirror that emotional frame of mind, and you have to keep working on it until that mirror is complete. It’s very easy to make music. It’s very easy to make a song that sounds like a song, that sounds complete, sounds arranged, and so on. It’s a little more difficult to make music that’s important to you, that means something to you individually and really resonates within you. And that’s the challenge, I think, of working in this context.”

Philosophically, many musicians believe that inspiration is something obtained from “somewhere else.” What is Sylvian’s view?

“I think the idea of being connected with that side of yourself, as I said a greater sense of consciousness beyond your own being, is to make contact with this kind of collective unconscious, which has many manifestations. But to plug into that is to plug into an enormous well of creative energy, and if the work surfaces at all, and has any value at all, it has come through you and not from you.”

Not unlike his ally, Ryuichi Sakamoto, David Sylvian has been offered many film scores, but he is reluctant to take on this mode of writing.

“I have so many projects that I want to do, my own projects, or collaborative projects of one kind or another, that are connected to my current interests or my needs, that when I’m offered film soundtracks or whatever, I tend to think that if I would take them on, they would just divert me from the more important work that I feel that I’m doing. It would take a very powerful script or a very visionary director to pull me away from what I was doing and get me involved in what they were doing, unless it was already connected in some sense, in some visionary way to the kind of area I was working in. The scripts you get sent…the ones that I’ve read and seen finally on film, they are so easy to imagine the construction of the films, you can read the script and already imagine what the film is going to look like. You can almost immediately guess what the director is going to ask for, musically, and so on. And that doesn’t feel like a challenge to me. It’s more like a functional job, but it takes a lot of skill to do it, and I admire the people that do it, but it’s a certain kind of application to be involved in, in making scores in that way. Very few people manage to produce music on their own grounds. You often have people coming in telling you they want you to sound like this or sound like that and so on. I’m just not interested in that. So unless the right project surfaces, I would like rather to just carry on producing my own work.”

In one of Sylvian’s own films, “Preparations For A Journey,” he demonstrated his personal skill for Polaroid art, drawing and his basic love for visual arts, including his desire for a yet-to-be-made film that would visually depict his life.

“The Polaroids came out of a period when I stopped writing and were kind of an extension of the drawing and painting I was doing. And I don’t place that much importance on all that at all, other than it being some kind of exorcism for myself, it was necessary for me to do that at the time I wasn’t writing.”

“I have got involved… just last year I did a gallery installation in Tokyo Bay, in a warehouse, which was a new experience for me and something I enjoyed doing enormously. That’s an area I would like to explore a little further. I worked with Russell Mills, the designer I work with often, on like Weatherbox and the Gone To Earth cover. We were offered this warehouse in Tokyo. We could use the space in any way we wanted to. There was a large degree of sponsorship involved because it was part of an arts festival, so we managed to conjure up something that was quite extraordinary. It was very difficult explain, but loosely, it was based on the concept of memory: personal, social, historical and the collective unconscious. It involved sculpture, photography, light, music and noise. It was incredibly interesting to work in this fashion, to take the kind of ideas and concepts that I’ve been using in music over the years and try to develop them in a three-dimensional form. I found that quite a fascinating work to be involved in. And actually, Russell and I are now putting a book together documenting the making of it, because it was site specific…and once it was completed the majority of it was destroyed, but we have some wonderful photographs of the whole event and sketches and so on.”

Will his gallery installations ever reach the United States?

“I’m just waiting for the offer. I’d love to come to America and do something along those lines. It really does depend on offers, because the sponsorship is so important. It’s not something you can undertake yourself. We’re currently planning to do something in Italy along the same lines. But each project, I think, will be site specific; it will be unique to that particular environment, and so on. So we really need people to call us up and say ‘well, we have this space, would you be interested in doing something in this space,’ and we would rise to that challenge.”

With a non-stop pace, Sylvian has many projects in the works. He has plans to continue his visual art installations, embark on a musical collaboration venture with Scott Walker, complete his new solo album, and possibly work with Robert Fripp again soon. There is not a scheduled tour for Rain Tree Crow, and although his last concert in Chicago during 1989 brought only a brief glimpse of Sylvian, another solo tour may not be far off.

“I would like to tour again. The last tour I did was problematic to say the least. Chicago was not a successful night. There were a few other nights like that, but not always related to my health. We had terrible organizational problems and technical problems and so on. And it kind of put me off again. I mean, I hadn’t toured for some time, this was the first solo tour I’d done. It just didn’t work for me. There were far too many problems, and when it was over I swore I wouldn’t tour again. I always say that after every tour I do. And there comes a period of reassessment, and I think “God, this is defeatist of me.” There must be a way of cracking this, there must be a way of doing it where I get as much pleasure out of it and I’m able to give enough to the audience to make me feel like it’s worth while. I’m kind of winding myself up, now, beginning to think about touring next year, after I’ve completed the next solo album.”

Elements of nature have been an important theme in all of Sylvian’s works, especially in the cover art of his albums, and his references to Shamanism led the conversation back to his beliefs and practices.

“[Shamanism is] really a metaphor for me. No, I don’t practice it. Of course I’m interested in the people that have in the past and the cultures and so on. It’s really a metaphor for the individual as Shaman, that you no longer need the second or third person. You don’t need somebody outside of yourself to instruct you as to who you are. You are in effect your own priest, your own Shaman, your own whatever. You can connect yourself to the God-head or the spiritual self or all the rest of it. Gone is the idea, I think, that you need these formal religions and these teachers, of one kind or another, that give you guidelines, very very loose guidelines, as to how to achieve that. I do believe there are some masters and some great spiritual teachers that have existed and continue to exist, and that is beneficial to be in contact with these. But on a much broader basis, the idea of formal religion and the kind of dogma that goes with that, I think, is dying, and should be. We are perfectly capable, now, of making this contact without any sense of guilt, shame or fear. It’s possible. The idea of the Shaman is just a metaphor for me for this kind of new age, this new way of looking at this inner connectedness.”

“I see the work that I do as a kind of by-product of a life experience, and the act of creating the work becomes part of the life experience itself, and feeds back into my life and informs my life in some way. It has this sort of cycling effect.”

“The understanding of who I am, the developing of a self-awareness and a growing consciousness, that is of utmost importance to me and is the backbone of the work, in a way. That is what guides me. That’s my motivating force in terms of wanting to create, wanting to share, wanting to give, wanting to grow within myself and have a fuller understanding of who I am in a complete sense, and wanting to share that with other people, not share who I am, but to allow other people to find themselves and feel what a rewarding experience that is and how much it opens up possibilities. The horizons become much broader in life once one comes into contact with, you could say, this consciousness or this spiritual side of one’s nature, and so on. These are givens. These are things I now work with, and the methods with which I approach the understanding of these things may change from time to time, and the philosophy may shift in focus from time to time, but I think there is a basis there which is consistent.”

“The journey never ends, in effect. The journey is everything. The arriving is not so important. It’s the journey that is important. There are times in life where you feel that you are getting closer to the center of things, or you are making contact with something that feels essential. Once you begin to make contact with that, what I found is that a whole new world opens up, which is positive, of course, that you can move on, that something else can take place. But on the other hand, you’re at the bottom of the ladder again and working your way up to the top. So you’re back at square one, you’re kind of floundering around trying to work out what this is all about now. You have the guidelines that took you to that point, but now you’ve reached this stage, and all those guidelines kind of go out the window, because this is a whole new experience, and you have to learn about this experience to take the next step. And it’s a very slow process to climb the rungs of the ladder, so it’s an ongoing journey. I don’t see that it comes to an end. It’s just a constant journey.

“I think that there is a reason for this development to take place. It’s for enormous development to take place. We are part of the earth that we’re on, as well as part the universe that we’re in. We belong to it all, we’re part-and-parcel of it, and what we do here consciously — what we develop consciously — effects this environment. As we talked about earlier on a small scale, the individual effects the society, society effects the nation, nation effects the world, and if you’re effecting the world, I mean, if you’re doing something on a global scale, if consciousness develops on a global scale, things will change within the world within the universe.”

So what future goals can a person with such resolute direction aspire to accomplish?

“I think the goal is always the same: to feel a peace of mind and an enormous amount of love.”