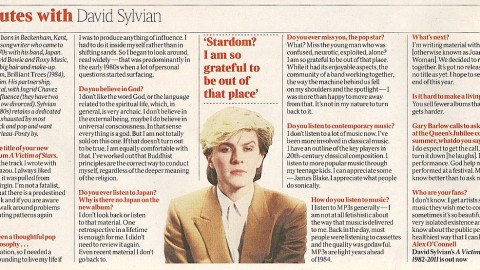

Independent interview (UK). Published online at independent.co.uk 27 June 2003.

David Sylvian: Songs from the fringe

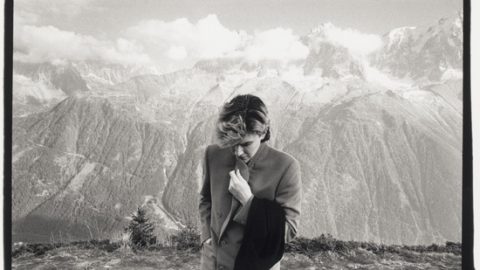

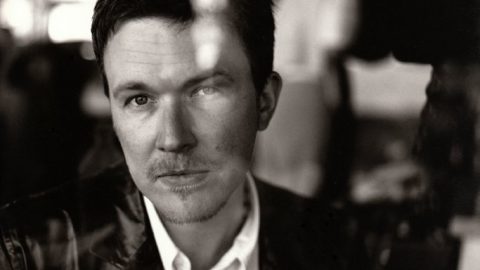

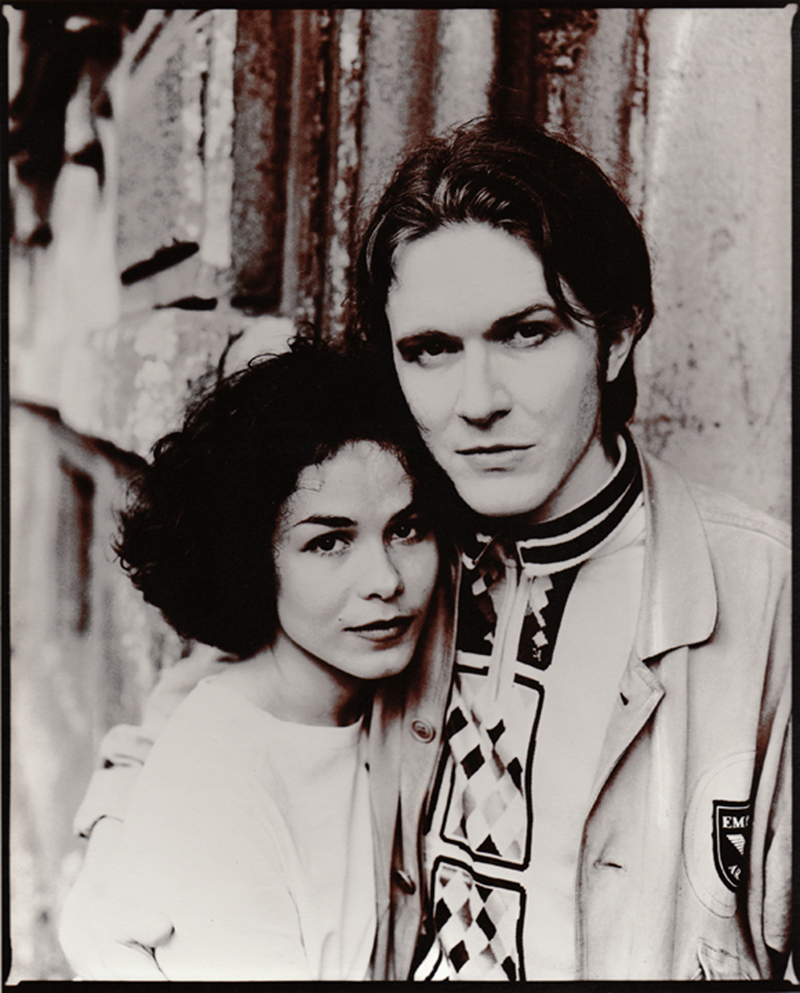

David Sylvian was a pop pin-up when he led Japan. Now, after years on the frontiers of the avant-garde, he has produced his most personal songs yet. Martin James talks to the man behind the big hair.

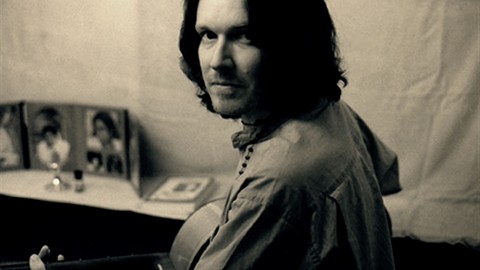

When the south London schoolboy band Japan heralded their late-Seventies arrival with a lipstick-smeared New York Dolls pastiche, they couldn’t have been more out of step with the mood of the times. It was the heyday of punk’s anti-glamour and Japan stood out like a silk scarf in a sea of bondage trousers. Ever since then, Japan vocalist David Sylvian seems to have been slowly disappearing from view, fading behind his own music.

By the time of their fifth and final album, Tin Drum, Japan could be heard turning their backs on the trivialities of pop culture with a unique East-meets-West sound. But it wasn’t to be: “Ghosts” became a Top Ten hit, Smash Hits voted Sylvian the best-looking man in the universe and pop slammed the exit door in Japan’s faces. Sylvian responded by going solo, and Japan disappeared once and for all. He drafted in musicians like Can’s Holgar Czukay, Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Ryuichi Sakamoto and legendary trumpet player Jon Hassell, and created textural explorations in free form jazz and electro-acoustic ambience for 1984’s inspired Brilliant Trees.

In the years that have followed he has relentlessly pushed to the outer edges of the pop culture radar. “I often think I’m already invisible culturally. My work is often viewed as being irrelevant – which is confusing, bewildering almost,” confides Sylvian.

He moved to America over a decade ago and lives in an 18th-century retreat in a forest, halfway up a mountain in New England. (He explains that his mountainside home was an ashram for many years “and has a concentration of energy that is inspiring”.) His image has changed from the Eighties-style New Romantic with the bleached, floppy fringe – a look forever imprinted on the public consciousness – to today’s lank hair and stubbly goatee.

But his musical ambition has refused to wane. As a solo artist, he has delivered beautifully crafted albums in which he has married avant-garde techniques with lush arrangements and poetic lyricism to often startling effect. This month sees the release of Blemish, his first album for his own Samadhisound label. It is perhaps the most direct offering of his career. Gone are the lush arrangements, and in their place sit detuned guitar-string tones, reductionist electronica and avant-jazz. Sylvian’s lyrics also offer his most direct, upfront and emotional work yet. If 1999’s Dead Bees on a Cake offered a celebration of love, then Blemish is a man dealing with the dark side of that same emotion, where truth is regarded as a blemish on the skin of everyday reality.

The key to the album is juxtaposition. Sylvian’s trademark up-close-and-personal vibrato vocals sit at counterpoint to disquieting musical arrangements. Take the 13-minute title track which finds his voice contrasted with layered, reverberating feedback tones and the sound of metal objects tapping guitar strings. This sense of opposite extremes finding common ground is at its most poignant on the three tracks that feature avant-garde jazz guitarist Derek Bailey: “The Good Son” is almost humorous in the way Bailey picks out muted notes alongside seemingly random chords in his attempt to find a tune, as Sylvian croons “He loves a good tune, so whistle one he knows,” his tongue seemingly planted firmly in cheek. The final, and stand- out, track, “A Fire in the Forest”, features the minimal electronica-scapes of Christian Fennesz, whose frequency snatches and stretched harmonics fuse ravishingly with Sylvian’s wistful melody.

“The subject matter is so personal that I can’t really go into it,” Sylvian says. “I was going through a difficult time, so the sound is more immediate and raw than the lush material people normally associate me with. It’s quite minimal in outline; it was a matter of getting the intensity right.”

Blemish is the first time that Sylvian himself is the main focus, no longer the disappearing man. And yet this is no work of self-obsessed egotism. “I had things I had to express but felt I had no one to open up to. I’ve always found it hard to open up anyway, and the immediacy of this project gave me the right focus. It is a confessional to oneself certainly, probably the most unguarded work I have created, but I have tried to express myself on a more universal level. I wanted people to find something of themselves in the work.”

Although the album lyrics speak of emotional trauma, there was another dilemma at the heart of this recording, one brought about through his career retrospectives for his former record label Virgin – Everything and Nothing and Camphor – which found him disappearing into his own past. “At the end of it, I felt creatively dead,” he admits. “It just wasn’t satisfying work, and because it took so long there was a long period in which I hadn’t had the chance to explore new work. I had to find out if there was anything worthwhile there. So I tapped into what was happening to me with openness and truth.”

David Sylvian embraced Buddhism in the early Nineties. There was, he says “no great epiphany, but rather an enormous curiosity.” His initial move towards the practice came with the emotionally confusing break up of Japan, but it was only when he found the teachings of his guru Sri Sri Mata Amritanandamayi, better known as Ammachi, that he fully immersed himself in the faith. “The guru’s teachings have an underlying principle which is born out of Hinduism,” he explains. “She teaches that it is possible to embrace the godless beliefs of Buddhism as well as the world populated by numerous gods.

“The whole New Age view of peace and light is just a partial view. If you are moving along a path of spiritual growth you have to face up to the darkest parts of your own human emotion. It isn’t easy; there are tremendous highs and lows. You don’t get off lightly.

“I’ve always believed in the divinity of life, and my practice is so much the foundation for everything I do. Even though the album covers difficult issues, my beliefs helped me fully inhabit the emotions. This can be dangerous, but I felt alleviated. It is all part of a spiritual journey.” Then he laughs: “I wish there were another language to explain this because terms like ‘spiritual journey’ are so Cher!”

From pop pin-up to reclusive artisan, from merely appropriating Eastern images and sounds to immersion in eastern spiritual practice, one thing that stands out about Sylvian is that none of his actions have been fuelled by ego; they have always been born from a sense of honesty. Indeed, unlike his Eighties pop contemporaries he has managed to escape the era integrity intact. Don’t expect to see him with Tony Hadleyand Howard Jones on a reunion tour. He’ll be working in his mountain retreat, quietly pushing at musical boundaries. “It wasn’t an intentional thing,” he says of his gradual fading from view. “My record company said that I wouldn’t do TV and press – which wasn’t always the case. And I haven’t buried myself in the mountains like a hermit!”

Instead, Sylvian has turned the act of disappearing into an art form.

‘Blemish’ is out now on Samadhisound, available through selected outlets and www.davidsylvian.com