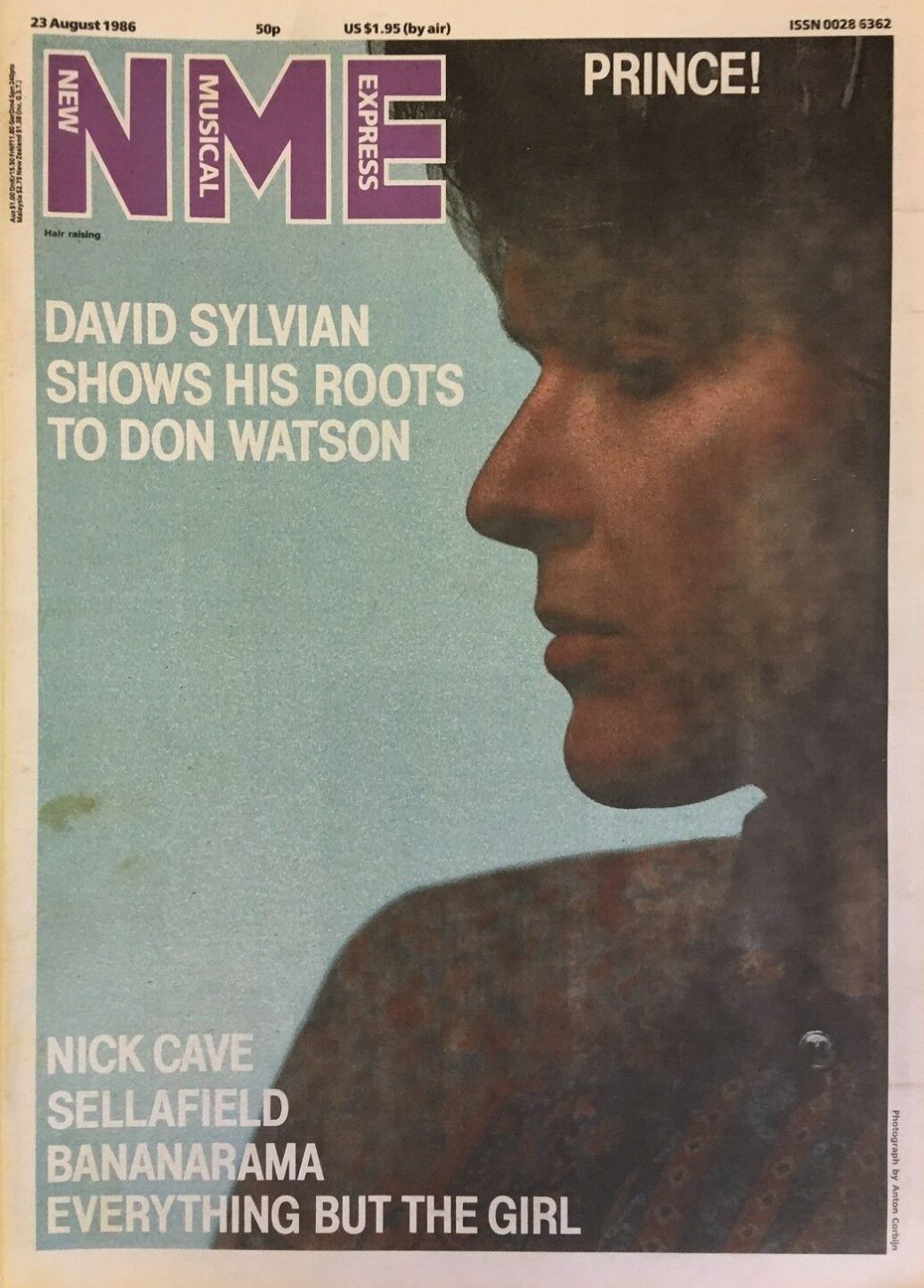

David Sylvian: Blonde On Blonde

by Don Watson, New Musical Express, 23 August 1986

TWO YOUNG men, once blond, face one another and indulge in the absurd activity of taking music seriously. “Almost too seriously,” says David Sylvian. The corners of a fine thin mouth twitch, downwards.

Is that possible? said the devil’s advocate to the angel of pop (resigned).

“I think so, I think I take myself too seriously. Since Quiet Life, I suppose it’s all been very serious, but I can never tell how many people are following what I’m doing with the same degree of intensity as I’m putting into it.

“I know I take it too seriously, but I have to produce what I do. If you take a few steps back from it, it really doesn’t matter. There’s so little difference between the commercially bland and the artistically adventurous.”

But before we enter the McLuhanesque blur of the Virgin megastore, should we not point out that there is a world of difference between you and Duran Duran, a world of worry? (Worrying, such an unfashionable activity, but so many people seem to do it.)

“I know, but it’s a contradiction within myself that I can’t resolve. When I’m involved in it, I think it’s so important and when I stand back it makes no difference.”

Is that not self-hatred? I take myself seriously but I can’t understand anybody else who does.

“It can be laughable. Just by taking a few steps back and seeing the pains I go to. It’s laughable, but it’s just my way of learning. It’s because I take it so seriously that I can step back and see the whole thing as laughable.”

Is this the age of laughter and forgetting? (“A mystic must not fear ridicule if he is to push all the way to the limits of humility or the limits of delight.” Milan Kundera, The Book Of Laughter And Forgetting). How do you see David Sylvian?

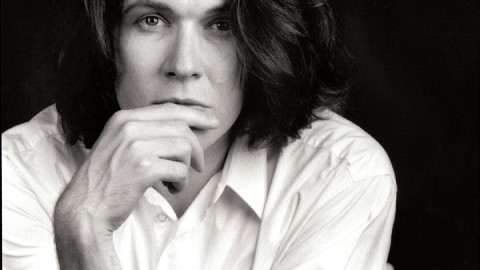

The devil’s advocate, ever the pedant, points out that until recently it’s been impossible to see him at all. Who could see behind the slow dazzle of a perfect image? All we saw was the stark and simple brilliance of Tarantula mascara peering through platinum blond. One of those images, like Siouxsie Sioux or Marc Almond, so prone to imperfect replication. Who could see Sylvian for his army of imitators, their flawed and lumpy images somehow, in themselves, marring the crystal clarity of the most beautifully applied make-up in the world?

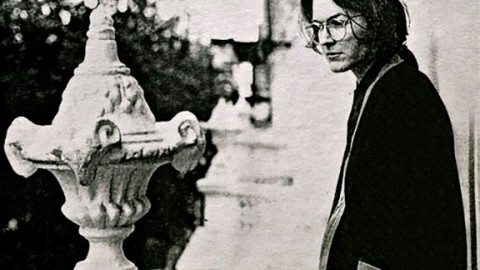

Now it seems that we can see Sylvian – shy, charming and (certainly) fragile. I am the third person to interview him since home-counties brown roots won out over Andy Warhol bleach-out. I am also the first to recognise him, and even then I was press-officer assisted.

“Embarrassing? No, I rather like it.”

A faint dust of downy stubble smiles with him. Unassuming sideburns jut a small way from under the reddish brown mop. Only the lightly tinted glasses look even vaguely familiar.

What is this David? The power of the unknown factor?

“Power? I don’t know, that sounds a bit strong, I just feel more comfortable this way. Before when people used to recognise me on the street, even just to say how much they liked the music, I never liked it. It always made me feel nervous and on edge.

“In the end I just used to avoid going out. I ended up in a really unhealthy situation, just staying in. Or if I ever did go out, I was driven from door to door. I’d always have to think of avoiding places where I thought I might be recognised. Now I can walk around more freely, and I love to walk.”

Was there a point at which you realised that you had ceased to become a person and had become a replicatable image?

“To a certain extent I purposely helped create that by having a Face as such. I was aware that people would copy it and could copy it. When I was younger I liked that idea, but perhaps when the national press picked up on Japan I could see in the articles that they were writing that the image no longer bore any relation to what I thought I was putting across.”

You decided you were not ‘Blond androgynous pop star David Sylvian’?

“Yes. Because it was all based on this ‘Most Beautiful Man In The World’ bit. When that ‘Scarred for life?’ thing came up on the front page of The Sun, that’s when it really began to hit. I was very uncomfortable with being a pop star – people waiting outside the door, changing phones every day.

“I’m shy by nature and suddenly I found I had all this piled on top of me. Maybe it was my own doing, but I decided I never really wanted it.”

THE IMAGE Of David Sylvian throughout the’70s somehow seems to trace the history of the decade – from emaciated brassy, Queenish, Dollish hedonism, through irony and imagery to artistry.

Two men, once blond, look at one another, and one asks the other. Did you have more fun?

“Not really, that hedonistic image we had in the first place with Japan was just so that I could put on a front, so that I could stand up and sing, otherwise I wouldn’t have had the guts to do it. When I began to realise that the whole music was a front then it began to become pointless. We caricatured our music as well as our image.”

Did that not engender some sort of schizophrenia – living the cartoonish image of sex ‘n’ drugs’ ‘n’ rock ‘n’ roll when your private life was…

“Anything but. Well we were very aware it was an image. At the time that seemed to be fun, but when you get older and realise the hollowness of the whole thing, you think you might as well do something of value or not bother.”

How do you listen to David Sylvian?

Five years ago I would not have been able to sit and listen to David Sylvian talk – for a start I wouldn’t have been able to take my eyes off him. Neither would I have listened to his music.

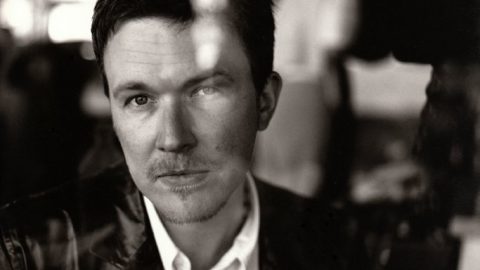

Nowadays I listen to very little else. While his contemporaries have progressed from being broadly fascinating into being narrow little postage stamp caricatures, Sylvian has moved in the opposite direction. He seems to be one of the rare figures who gets more interesting as time goes on.

Where in the ’70s and early ’80s he seemed to go with the flow, riding the cultural currents quite effectively, he now seems to be, like all truly hip people, working against the current. As the late ’80s descend into a travesty of frivolity and defensive irony, Sylvian has the nerve to be serious, the realism to acknowledge that it doesn’t matter all that much, and the application to learn something. Unlike prissy Miss Morrissey, who embodies some of the same qualities, he also thankfully realises that the drama queen is dead. To proclaim the cultural bankruptcy of today is to state the obvious, to subvert it is another matter. Morrissey seems incapable of deciding what to do, Sylvian has already decided.

The ‘Forbidden Colours’ (the vocal version of the soundtrack to Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, by Ryuichi Sakamoto); the first solo LP Brilliant Streets; Alchemy An Index Of Possibilities (the cassette featuring the EP ‘Words With The Shaman’ and the soundtrack ‘Steel Cathedrals’); and now the second LP Gone To Earth, complete a body of work galvanised by the discipline of self-application, haunted by the echo of solitude. Sylvian goes both further out and deeper in than any of his contemporaries.

“Some years ago,” he says in his statement on the LP, “I became interested in ideas I’d picked up from various sources of literature concerning a purity of form achieved by an economy of means, enabling a more direct form of communication between artist and audience.”

His interest in Mishima, Cocteau, Sartre and, on the new LP, the Czech author Milan Kundera, have been well signposted throughout the work, indicating not a retreat into literature, but an advance into the values spawned by the most solitary of art forms. But direct? Surely writing is also the most indirect of art forms?

“Perhaps that’s why writers have struggled with the idea of making it more direct, and I felt I could apply that to music as well. There’s so much decoration in music, so much frivolity of form that’s only there to keep the listener’s ear interested in a superficial way. It is a temptation to do that.

“When I got to Tin Drum I tried to cut all of those things out, to just get down to the most basic elements.”

It seems like an austere conception of music.

“Perhaps, because I’d been playing for so long with pop music and its components of ego, image and style. By the time I got to the second side of Brilliant Trees I really felt I’d succeeded in breaking all those things down. I can listen to that now and not cringe, whereas with the Japan stuff I just can’t listen to it, because I know it’s just well brought out images.”

Tin Drum was still playing with images, albeit images of austerity.

“It’s playing with images, but in a tongue in cheek way. ‘Visions Of China’ is about people using an image and knowing nothing about the culture, which is something that all pop music is involved in and it’s a vacuous lie, it’s superficial and it means nothing.”

And yet Japan were the worst offenders in that sense, using a second-hand Aladdin Sane conception of the country. It was the cheapest form of cultural appropriation.

“Yes.”

And yet in recent work you display a deeper understanding.

“I think I had to come to understand them, otherwise I would have continued producing music of little or no worth. Growing up and maturing is all I can put it down to. Things happen very fast when you’re in a group, you never have time to sit down and think what you’re doing, or what the point of the whole thing is. After Japan split up I stopped writing because I was unable to pin down any of my true emotions. I realised I’d never succeeded in doing that, all I’d produced was a series of acceptable images of my emotions.

“‘Forbidden Colours’ was the turning point, I realised that I was able to write something very honest and very open and very true to myself, without hiding behind images, so gradually I began to break those images down.

“I occasionally have lapses into things that people expect me to be. It’s difficult when you’ve been brought up in a pop world and that’s the thing that pop thrives on.”

‘Forbidden Colours’, of course, is named after Mishima’s novel about homosexual love. It’s often puzzled me that that seems to be what the song is about.

“Yes, it does come out like that, but I think the only way to write about anything that relates to fighting within yourself is to do it on a one to one level, without being too high minded about it. I like to keep things, as you say, austere. I like that idea that everything is as basic as possible. People relate to things in a way that often they don’t understand themselves, they take it on a surface level and yet the deeper meaning is present on a subconscious level.

“In a lot of ways, ‘Forbidden Colours’ would only come across as homosexual – the love of self. The idea comes up again on ‘Bullfight’ on the new LP. To fight the bullfight is to fight the animal side of yourself.”

That’s a very oriental concept.

“Middle Asian certainly. Spending as much time as I do in the East I obviously have a viewpoint on it, and with my girlfriend being Japanese I get another viewpoint. I’ve soaked up so much about the place that I’m almost not aware of how much I do know about it. Obviously there’s something very special about it to me, but I think that’s something that was in my personality in the first place, that fits in with it. There was something within my nature that fitted in with certain aspects of the culture.”

One line in ‘Before The Bullfight’ that intrigues me was “Guilty of stealing every thought that I own”. That seem to suggest a doubt that you have anything original to contribute.

“In a lot of ways I think that musically and in every other way everything that you produce is just the intersection of what you’ve perceived. But there’s a line at the end: “When everything’s forgiven every fault’s my own “. Your faults, I believe are the only things you learn from.”

You mean making a mistake in your copying of something is your only element of originality?

“Yes, that’s something that Cocteau said which I liked very much. I forget which book he was talking about of his, but he said in writing it he was trying to copy this other book. He said he failed totally and that was what he ended up with. That’s a good example of originality, trying to copy something else and failing miserably.”

WHEN LISTENING to the sense of solitude on Brilliant Trees I found myself unable to cast off the shadow of Miles Davis’ Sketches Of Spain.

“That was certainly a reference point, in fact perhaps ‘Before The Bullfight’ has something more to do with Sketches Of Spain in a more obvious way. I was listening to that kind of music and that album in particular during those periods.

“I find you relate to things that have an affinity to something already within your character, so it can enhance something that is already there and bring it out in a clearer, more defined way, and maybe listening to that kind of music has helped me. It definitely has.”

One of the best descriptions of Davis’ playing is “the sound of a man walking on eggshells”, which could apply to your own later work.

“There is that element to it, that fear of making a mistake. There’s the element also within myself of finding understanding so hard to pin down, you think you understand yourself but it’s such a fine line, walking a tightrope, one minute thinking you’ve got it right and the next minute finding yourself flat on your face, finding that something did not relate to yourself at all, rather to an image you had of yourself. There’s certainly that edge of fragility to it.”

Do you always pursue the spiritual rather than ever embracing the violence of the physical.

“Well it’s a very small part of my character and so it tends to be a very small part of the music. Maybe on Brilliant Trees it would be ‘Pulling Punches’, on this one it would be ‘Gone To Earth’, but because it doesn’t constitute a large part of my character, I don’t think I could produce an album’s worth of music, it would mean a fundamental change in my character.”

At the same time ‘Pulling Punches’ seems to display almost an affinity with physical suffering.

“Yes, the desire to understand, then a kind of anger at the inability to understand, the idea that if you’re living your life and think you know what you’re doing, you’re sleeping on your feet, you’ve got no idea, you’re not in control. That comes out in anger and frustration sometimes, which is just what ‘Pulling Punches’ is, ‘Gone To Earth’ is really rather similar in that it’s about the fact that most of the things that I see of value in the world are trodden down, the value is not seen, agggression is always used against it. That track is the nearest I’ve got to what I’ve been aiming at all this time, just because it’s so raw. It was almost recorded live, with no overdubs.”

One of the main things that’s always been said about your solo work is the sense of solitude that it embraces. How do you resolve the duality of being alone and living with someone else?

“I find it difficult, we both find it difficult because neither of us are the kind of people that thought we would ever be living with anybody else. We manage to live very separate lives, in a very small space as well as being very close to one another. I didn’t think I could do it and it has been very difficult, but it’s been such an education. It brought out sides of me that I kept buried, my lack of patience and the aggression came out. It’s much more of an effort to control these things when you’re living with someone.

“I know people who live on their own, and they are very happy that way, but that’s because they never put themselves to the test of living with someone else. It is such an education. Maybe when the learning stops there’ll be no point to it.'”

Since so much of of your work is a struggle to understand yourself, how do you react to someone who feels they understand you.

“I find that one of the pleasures is the surprise that someone understands you perhaps more than you do yourself or times when you feel an affinity with each other which has no words and has no sense in the material world. You can just look at one another and know that there is happiness inside the other person although your material circumstances may be awful. That thing which makes you think it’s worth continuing searching, because you know it’s there.”

Some of your songs do seem to be quite naked love songs.

“Yes they operate on two levels, one a one-to-one level, a man-to-woman level, and then on a higher level too. Both are relevant and both are intentional.”

THE REFERENCE to ‘Laughter And Forgetting’ is obviously to Milan Kundera’s book, but you seem to use it in a different way. It seems to be about the lack of cultural value in the modern world, about the tyranny of the ‘good time’, of laughing and forgetting.

“I certainly wrote it in that way, they were intended to be satirical lyrics, rather than romantic as they may appear at first. But as time’s gone on I’ve seen different levels of integration to it. Laughter is the lightness to be able to stand back and say ‘This is all worthless’ and in that sense you can stand away and see more clearly what you’re trying to do, not just in music but in life. Forgetting is the ability to not dwell in the past on things you’ve done which are wrong, or things inside you which are wrong, it’s a kind of overcoming of yourself, of the fear of failure.”

The two young men who used to be blond looked at one another and thought of the adjectives that might be applied to their conversation: “pseudo-intellectual”, “pretentious”, “academic”, “over-serious”. And they laughed.

And on their laughter they were borne on high, until the only thing left in the room was their brilliant…fading…laughter.