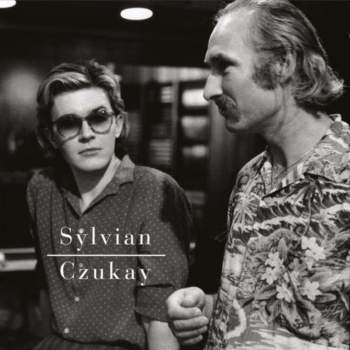

The last two years have been a period of transition for David Sylvian, but he’s now in a new collaboration with Holger Czukay and a new solo single and a major retrospective set of his post-Japan recordings scheduled for November release.

PAUL LESTER reports on one of rock’s most enigmatic figures.

“I like to introduce a provocative element into my music, something that will throw you. It’s too easy to create a sound with a fluid quality that doesn’t disturb. The whole point is to disrupt whenever possible. I’ve written songs about suffering where my concern has been to produce a sense of unease. Because the unease is there, it’s in me. There’s definitely a major change going on in my life. The past two years have been very difficult, a period of transition. Changes are always painful, but I haven’t lost sight of the basic beliefs and understandings that have enabled me to get through it all. There are days when I wake up and wonder whether it’s worth it, what am I doing here, and so forth. But you soon come to your senses. What is important to me now is to have a purpose and a fascination with all aspects of living.”

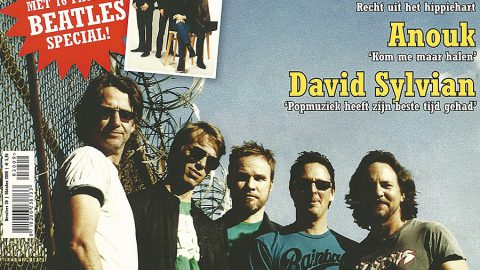

Whether David Sylvian is feeling uneasy or fascinated today is hard to tell. Maybe both. Whichever, there are a host of new releases to help us unravel the Sylvian enigma. Awaiting his first interview since 1987 in the subtle grandeur of a West London hotel bedroom, Sylvian is to talk me through a series of records that for him constitute an unprecedented burst of activity. First in the shops is “Flux And Mutability”, Sylvian’s second collaboration with Holger Czukay, the successor to 1988’s “Plight And Premonition”. October sees the release of “Pop Song”, a remarkable single even by Sylvian’s standards, while in November “Weatherbox” will be upon us, a CD collection of Sylvian’s albums and an excellent way to investigate his post-Japan history.

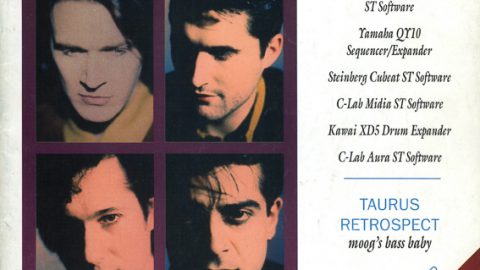

Standing by the window of the bedroom, Sylvian bears no resemblance to the preening blond longhair who graced the cover of “Adolescent Sex”, Japan’s 1978 debut LP, nothing like the intellectual glamour-boy who adorns “Tin Drum” or the lecturer-Adonis of “Brilliant Trees”, the last of the sleeves with a picture or photo of Sylvian. Today, he has chocolate-brown, shoulder-length hair that has no identifiable style; he wears slipper-type shoes, beige trousers and a green and cream, patterned shirt. He is as far removed from his previous incarnations as his current music is from those early Japan albums. Only the faintest trace of South London remains in his voice.

With “Weatherbox” assembling the serene beauty of “Brilliant Trees” (1984), the cassette-only “Words With The Shaman” (1985), the river-deep mountain heights of the double set, “Gone To Earth” (1986) and the tortured soliloquies of “Secrets Of The Beehive” (1987), I asked Sylvian how he viewed his history now.

“As you move away from something, it’s easy to forget the amount of passion that went into making it. So you look back with a certain critical eye, thinking how much better something could have been done, how you deceived yourself or found yourself playing the game. Time gives my work a fresh perspective. Also, working with the material live on our “Around The World In 80 Days” tour last year meant that I had to go back and hear those records again, which was kinda refreshing after being so familiar with them. My enthusiasm for, say “Nostalgia”, “Weathered Wall” or “Before The Bullfight” was rejuvenated.

On the other hand, I noticed that there were terrible failures there, things that I could’ve done far better. That doesn’t surprise me, though, because I know at the time when I can improve on something. It’s just saddening to go back now, hear songs again and know that I was right all along.”

As consumers, there is always the temptation for us to delve into the lyrics of our favourite artists, to glean some personal information about their lives. If the words prove too inscrutable, we turn to newspapers to extract the truths that we have struggled so long to find. But Sylvian has had a less then comfortable treatment from the press in his decade or more in the public eye, notably the cheap-shot investigations of the gutter rags a few years back when Sylvian was supposedly involved in a horrific car accident that reputedly scarred “the most beautiful man alive” beyond all recognition. He is, therefore, fairly adept at parrying, the prying enquiries of journalists.

Even less revealing, because it has no words on it at all, is “Flux And Mutability”. In turns restful and dramatic, tranquil and emotive, the record is divided into “A Big, Bright, Colourful World” and “A New Beginning Is In The Offing”, an involving piece of instrumental music whose quiet storm interference is organised by Sylvian and Czukay. “Flux And Mutability” uses ambient textures and repetition, as well as contributions from Can mainstays Michael Karoli and Jaki Liebezeit. Markus Stockhausen (son of Karlheinz) is in there somewhere, too.

What ideas or thoughts were you exploring on “Flux And Mutability”?

“Emotionally, the subtitles give a hint of how I personally responded to what was happening on the¬†¬†¬† record. The music originally had lyrics that Holger and I were going to narrate. For Holger, the piece¬†¬†¬† represents his fascination with the unknown, tuning into radio stations from far-off places when he was¬†¬†¬† young, hearing things he didn’t understand. All of this fired his imagination, and I picked up on this wonder for the real and imaginary worlds of childhood very quickly.

“The way Holger works is quite different to the way I work. He’s not looking for good, technical strong¬†¬†¬† performances. He prefers the moments before you get to that stage, when you’re dabbling, unsure,¬†getting lost and finding your way. He records that! Holger brings out a kind of honesty, a genuineness that, as professional musicians, we mask a great deal.

“In that respect, Holger and I have a lot in common. Our records are made intuitively, not intellectually. “Flux” isn’t daunting and inaccessible. People should decide what they want from it without fearing it’s too abstract. If they get something ‘superficial’ from it, fine. You don’t have to respond in a certain way. It’s definitely not precious, either. I hate that.”

Evading questions about his “difficult” two years off, Sylvian is even self-effacing about the music that he makes, his work on “Flux And Mutability”, his (lack of) instrumental prowess. Eager to shake off the “precious” and “pretentious” tags that have dogged his career, Sylvian is more frequently wry and self-deprecating than anyone would guess. So, if we are to learn anything about the private sorrow of David Sylvian, the implied changes in his life and attendant upheavals, we shall have to read carefully between the lines, study the records, realise that, behind Sylvian’s easy humour and casual affability lies a world as complex and intriguing as our own.

This is as exciting a time as any for Sylvian. A box-set retrospective, a second valuable association with Holger Czukay, and “Pop Song”. Having travelled far away from the mainstream success that brought Sylvian massive chart, TV and magazine exposure in the early Eighties and openly expressing his dissatisfaction with that success, he now releases his most deliberately commercial record for ages. [..!?] “Pop Song” is a highly infectious single that openly grades its mastery of the pop form, a soft, insistent beat and a dry, sardonic lyric that should return Sylvian to the place he’s been eager to escape from for the last decade – the Top 40. “Pop Song” will sound brilliant on daytime radio.

“It’s a strange piece, a real one-off. A lot of different interests brought it into being. It rekindled the fascination I had when I went into music in the first place, and it got me working with synthesizers again. Lyrically, it’s kind of playful, dealing with what I see in popular culture which is, basically, a waste of creative potential and a willingness on the part of the public to be a party to that, to a lost believe in popular culture more than their own lives.

“It frightens me that people depend so much on those vacant icons which give people nothing in return. ‘Pop Song’ doesn’t delve too deeply into all this. It’s playing the game, in a sense. Being subversive from within.”

In 1981/82, when ABC, Human League, The Associates and Japan were, in a way, terrorising the mainstream with their provocatively contrived pop grenades, there was talk of subversion, of fooling around at the centre of things, being disruptive. David Sylvian left all of this behind when he disbanded Japan over six years ago to pursue a solo career that has been astounding for its comparative silence next to the furore that surrounded Japan. That Sylvian should want to dive back into all that in 1989, albeit for a brief and critical dip, is quite incredible.

What would happen if “Pop Song” charted and, once again, the public established you as an idol?

“You may say I’m wrong, but I don’t think I’d allow that to happen, allow myself to be established as a popular icon figure. Besides, I don’t think it stands a chance of doing anything in commercial terms!”

Would you like it to?

“Yes, of course, because the whole point of it was to make a statement from within the media that I’m

criticising.”

Does the idea of disrupting the normal flow of things with a record as witty and lovingly crafted as

“Pop Song” seems very exciting to you?

“Really, I don’t get too much satisfaction from writing pop songs. To do that you have to play the game completely, create a physical image, and I’m not interested in that at all.”

“No, it’s misguided and it weakens the strength of the work. I know, I’ve been through it all, but I feel it’s wrong.”

You don’t think life would be empty without the lust we have for our heroes?

“Why should lust disappear just because icons disappear? I’m not saying popular culture’s got it all wrong, just that there needs to be a balance. There are elements of life that are totally ignored, the knowledge of which is not made available to people of a certain age when they become interested in other aspects of existence than their sex life.

There is a positive function to be had by working within the popular medium, but people’s readiness to escape into that, to fill a hole in their lives with it, that runs counter to what popular culture really represents.”

If we haven’t discovered all there is to know about Sylvian’s emotional make-up, that’s because he’s harder work than most of his peers. Not for him the off-the-cuff admission or conspiratorial aside, those enlightening platitudes that are cleverly designed to seem giveaway and revelatory but that are, in reality, engineered weeks in advance. An hour with David Sylvian told me nothing… and everything I need to know.

“I actually think I’m moving closer towards the centre of things,” he says finally. “We probably have different ideas about where the centre is, but I’m getting closer to the truth, or trying to at least. I’m aiming towards something that has a closer touch with reality. I don’t pay too much attention to the business or media in general. I’m out of touch with that world, definitely. It hits me occasionally and, when it does, it seems strange… and more than slightly pathetic.”