David Sylvian on his new album Manafon on walesonline.co.uk.

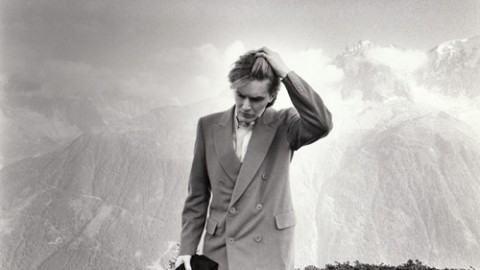

For his latest album David Sylvian, the former frontman of seminal ‘80s band Japan, takes inspiration from the life and work of Welsh poet RS Thomas. Long-time fan Hannah Jones exchanges emails with him to understand the meaning behind Manafon

Q: Let’s start with the word, Manafon. Tell us about the connection of your new work to this one word, which is a place in Powys.

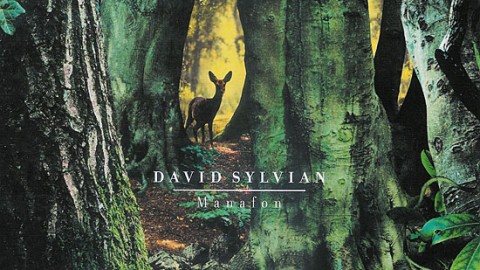

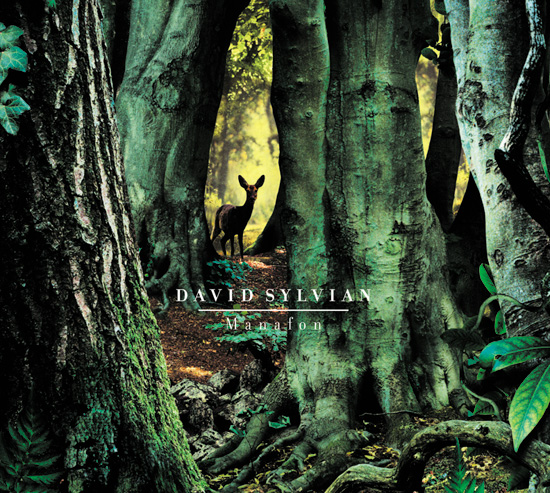

A: I came across the word in relation to the life and work of RS Thomas. It was the location of his first parish and the place where he wrote his first three volumes of poetry. Over time the word became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination, the creative mind or wellspring, hence the cover art of the CD depicting an implausible idyll if you will. A place where the intuitive mind taps into the stream of the unconscious.

Q: When did you first come across his work?

A: A dear friend introduced me to his work back in the ’80s. She’d loved the title of the volume of poetry she’d stumbled across and knew that the fact that he was a priest would interest me, particularly as his poetry struggled with issues of faith.

Q: In the title song, Manafon, you refer to Thomas as a “man down in the valley, who doesn’t speak in his own tongue”… a man who “bears a grudge against the English”. The song doesn’t paint him as an attractive individual, which I guess he wasn’t for some. What is it about him that inspires you?

A: I don’t feel the piece paints him in an unflattering light. It’s a bare bones character study which, if anything, presents a man for whom there are no easy answers. There have been books written about the man since his death that can better pinpoint the contradictions he embodied. It’s not a matter of what inspires me so much as what he represents for me. In some ways this austere, cantankerous old man is my grandfather, a man out of time. Rigid, damaged, wounded, immovable. On another level it’s the ideals he tried to live by, the discipline and austerity he adhered to and imposed on others. His desire for self betterment, for answers to life’s big questions, but also the role he might personally play in the uplifting of his people, society. His over identification with a nation to which he, in a sense, didn’t fully belong. So there was this quixotic element to his personality, it seems to me, a tragicomic element that wouldn’t look out of place in one of Beckett’s plays or novels. In fact he’d fit in beautifully. Then again, there’s the poetry which can be idealistic in its praise of the working man but can be profoundly beautiful and moving too. His own questioning of God’s silence. Well, he railed against it at times as if faith had abandoned him. There’s such a rich complexity there and we’re only scratching the surface. These contradictions, the multifaceted character, although something of an anachronism in his own time, in some ways anticipates a contemporary predicament.

Q: Thomas was a man with a strong but complicated personal faith. Does that resonate with you?

A: It’s a matter of defining for oneself what gives one’s own life its shape and form. What are its defining characteristics, its sense of purpose? With Thomas, the poet and the priest are inseparable but for me it’s the poetry which best gives his life its true definition. The freedom, ability, and the process to openly question aspects of his own faith, which I can only assume helped his personal growth in some manner, must’ve acted as a considerable release for him. As a man of faith, as rector, his approach might have been too austere, out of touch, to the degree that it alienated people but his poetry expresses his humanity which, at its best, rises above the specifics of faith and national identity to speak of the universality of the human condition. He dug deep into his own soul, as corroded and damaged as it might’ve been, and spoke with as true a voice as he could muster.

Q: Thomas isn’t an “easy” poet. He and his wife hardly ever spoke to each other, and only met at meal times. Yet after her death, all these amazing poems started pouring out. Does love, or the notion of it and its difficulties, influence your work?

A: I would say the necessity and desire for love is an important underlying theme for me. This issue lies at the heart of a piece such as Emily Dickinson (on the album). It’s a fact of life that not everyone experiences unconditional love, finds themselves or others unlovable, aren’t willing to give, to sacrifice for the sake of love. Some simply cut themselves off from it. Withdraw. Yes, the theme of love or its absence is a constant preoccupation.

Q: How did you musically approach this new work? It certainly feels more easily experimental, picking up where your album Blemish left off.

A: I used the same approach that I developed when working on Blemish. This involved improvisational performances accompanied by a process of automatic writing. I expanded this approach by embracing the input of larger ensembles recorded live in studios in Europe and Japan. At the outset, I wasn’t sure if or how this was going to work in practice but after the first sessions, which were recorded in Vienna in 2004, and which resulted in a number of the pieces you’ll find on Manafon, I knew I had unearthed an exchange which could yield fascinating results.

Q: The music is kind of free form, or at least that’s my impression. The melodies come from the voice. Is this a deliberate device?

A: Yes, the music is entirely free form. From my vantage point the melodies are suggested by what I hear in the improvisations. Whereas the musicians were playing with enormous restraint, I worked against genre if you will, and developed the lines that I heard suggested or alluded to. I used atonal sounds as punctuation, queues, a suggested key. Where necessary, I added my own musical contributions in the form of guitar and electronics.

Q: What are the stand out tracks for you?

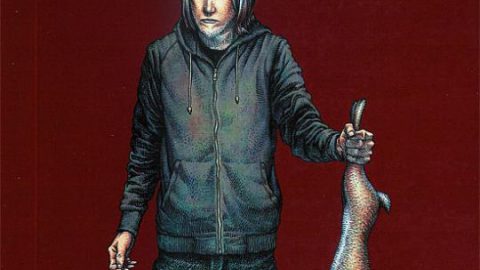

A: The greatest challenge was presented by what became The Greatest Living Englishman, so that’s the centrepiece of the album for me. Melodically I’m fond of Snow White In Appalachia. The Rabbit Skinner is possibly the most autobiographical lyric on the album. It is an album that is conceived as a single entity though. A “song” should stand up alone just as a poem, removed from the body of a book of poems, should do also. But to understand and benefit from the full resonance of the poem it’s best read in the context of that body of work. Of course, this is a decision each individual is free to make for themselves but it should be remembered that the album is a meta composition composed by the artist.

Q: Do you consider the listener in your work, if they will like it?

A: To create a work of any kind is an act of communication, therefore the aim is to lend the material as much clarity as is possible without compromising it in any way. You work in service of the composition. It makes demands and you do your best to adequately respond. Of course one cares what listeners take away from the experience but what you can’t do is anticipate a specific audience’s response to it or have one in mind while creating it. The strength of a piece comes from its internal logic, that it is true to itself. That the piece might speak to a very small number of people isn’t its concern. The main consideration is that the essence of the work is uncompromised and communicated to the best of your abilities. As to whether people like it or not, I’d prefer to think that with a work like Manafon, they’re possibly having an audio experience unlike one they might’ve had before. There’s no intention to repeat an experience someone might’ve had, say, with Brilliant Trees. We’re saddled with our past for better or worse but each individual release should rise or fall on its own merits. I’ve always had to deal with the fact that, whatever I produce, I will upset or alienate a proportion of my audience, occasionally to the point of losing them altogether. Some might complain the work is too “out there” while others complain that the work isn’t experimental enough, that I’m merely repeating myself. I guess I’m one of those infuriatingly “inconsistent” artists who don’t tailor the work to any specific market therefore there will always be dissenters regardless of what I produce. Having said that I am incredibly grateful to those who’ve stuck with me and taken pains to understand the reasons and the possible benefits for the, sometimes radical, changes in my output.

Q: Some people would still like a less experimental Sylvian album; dare I say it, Secrets Of The Beehive II. Can you see there ever being more work in this vein or is the process of exploring new creative avenues more important?

A: On hearing Manafon for the first time, a friend and musician by the name of Jan Bang told me that, for him at least, Manafon served the same purpose as Secrets Of The Beehive – it was its contemporary reflection. I was grateful to hear that. It’s an observation I wouldn’t disagree with. I’d also point out that, at the time of Beehive’s release, the critics were not kind but openly dismissive or downright brutal. Consequently, it initially sold quite poorly. It’s easier to see things clearer in hindsight perhaps. Manafon doesn’t sound wildly experimental to my ears. Nor do I personally hear it as being a difficult album but I’ve always known the experience would be different for others. Time will soften its edges. It may sow the seeds for what might develop into a new genre for vocal music perhaps. Or maybe it’s simply a passing glitch on the digital face of popular music. I don’t know. But what I am sure of is that over time its abstractions will become much easier to embrace. After all, Debussy was considered impossibly avant garde in his time. It’s hard to credit such a response to his music today. Similarly, Brahms’ Piano Concerto No 1 was reviewed in its day as “noise”. We need to grow into modern works. We shouldn’t ask that things be made too easy for us. Having said that, I haven’t abandoned form entirely. I may make a return to it at some point. For now, I’m leaving all possibilities open. Manafon is out now on SamadhisoundI came across the word in relation to the life and work of RS Thomas. It was the location of his first parish and the place where he wrote his first three volumes of poetry. Over time the word became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination, the creative mind or wellspring, hence the cover art of the CD depicting an implausible idyll if you will. A place where the intuitive mind taps into the stream of the unconscious.

Original article on Wales Online