Online version of the feature in the magazine of The Observer, April 10th 2005.

By Jason Cowley

With their dyed hair, poetic ambitions and liberal use of eyeliner, Japan gave a sense of identity to a generation of disaffected suburban teens. Among them was Jason Cowley. Twenty years on, David Sylvian, the band’s frontman, talks about his latest solo album and his life as an old New Romantic

I was 16 when I discovered Japan were splitting up, just as they seemed poised for prolonged mainstream success, both here and in the United States. It was the summer of 1982 and I could not have been more disappointed: Japan, in those days, meant everything to me. They influenced the way I dressed, what I read, what I listened to and with whom I was friends. And their influence on me would continue, in various ways, long after the band was no more.

I was an intensely active teenager, sports-obsessed. It was only through becoming interested in Japan that I learned to be calm, to think more seriously about myself: the kind of person I wanted to be, and where I wanted to go. For a period, I dropped out altogether, abandoning my A levels, to spend long, empty afternoons and evenings with my friends dreaming up elaborate plans for the future: we wanted to form a band, but we couldn’t be bothered to learn any instruments. Our approach to our putative pop career was, then, cerebral and exhibitionistic; we liked the talk, and we liked the clothes and the make-up. What was the use of doing great things, to echo Jay Gatsby, if we could have a better time telling each other what we were going to do? But you can talk and equivocate only for so long; at some point you have to act, if you are not always to live vicariously through the achievements of others, in the twilight of fan-dom.

Japan comprised singer-songwriter David Sylvian; his younger brother, Steve Jansen, who played drums (the brothers had, in disaffected late adolescence, changed their name from Batt); the multi-instrumentalist Mick Karn, with whom Sylvian had a competitive, often destructive relationship; and the keyboard player Richard Barbieri. They had started out, having met at school in the south-east London suburbs in the late Seventies, as a raw, post-punk, New York Dolls-inspired combo, managed by pop impresario Simon Napier-Bell, who would later work with Wham! Yet because of their coarse lyrics, long dyed hair, their screaming guitars and their general artlessness, Japan were sent out on tour, by their record company, Hansa, as the support act to rockers Blue Oyster Cult. This early experience was one of complete humiliation: when they were not being pelted by coins and cans by greasy bikers, they were emphatically ignored, as were, in time, their gauche early albums, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives.

Japan’s third album, Quiet Life (1980), was an improvement, a fusion of rock and the new synthesized pop – ‘futurism’ – and one of the most innovative records of the year. In many ways, it was too innovative. It certainly made little impact on the charts and they were dropped by Hansa.

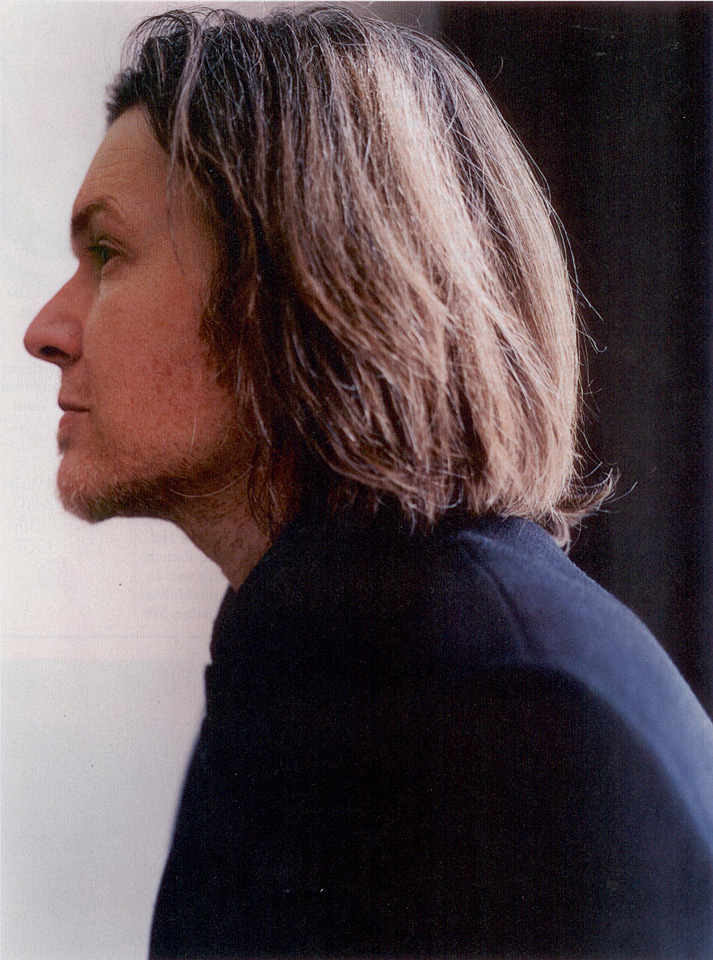

From such beginnings, there should have been no way forward. But Japan were different and it was this difference that attracted me when I finally caught up with them at about the time of the release of their fourth album, Gentlemen Take Polaroids. They were, like a lot of restless working-class boys from the desolate suburbs at the time, intelligent, if uneducated, and seeking ways of self-expression. They wanted to improve. Influenced by David Bowie and Brian Eno, they were experimenting with computers, sampling techniques and synthesizers, new technologies that would transform for ever the way music was made and recorded. And, in Sylvian, they had a fascinating frontman, a wan, withdrawn Narcissus. With his long, thick highlighted fringe, his make-up, his fine bone structure and his wilful embrace of androgyny, he looked like a cross between a younger, more beautiful Andy Warhol and David Bowie as he appeared in The Man Who Fell to Earth. In return, many people tried to look like him, from Nick Rhodes of Duran Duran to Lady Diana.

There was something fragile and exquisite about Sylvian that appealed both to men and women; he had the mystery and allure of a Hitchcock blonde. ‘When I first met David he had very long blond hair and the most extraordinary sense of style,’ Simon Napier-Bell told me. ‘He had talent, but it was not focused. What he had, though, was a tremendous desire to succeed and the will to carry the whole thing through. From the beginning he was in control; he knew what the music should be and where it should go. I knew, with him, we could be as successful as we wanted to be.’

Sylvian was a reluctant pop star. He did not want, as it turned out, fame and immense wealth. ‘He told me later that he wanted to have the profile of a French Left Bank poet,’ Napier-Bell says.

It is hard to exaggerate the effect Sylvian had on a generation of neurotic boy outsiders, both in appearance and attitude, in the often drab and brutal suburban England of the period. In interviews, he would speak of his shyness and of his desire for solitude. There was seldom any mention of the usual rock ‘n’ roll excesses: the drugs, the girls, the trashed hotel rooms. He was, rather, interested in Japan the country, where the band were received with early enthusiasm, and in the visual arts and literature. He was dissatisfied with western secular materialism – in time, this restlessness would lead him to Buddhist meditation, ritual worship and Hindu mysticism. His opaque lyrics reflected his wide reading and his sense of dislocation.

‘Thinking back on Japan,’ Sylvian told me when we met recently in New York, ‘I led a very isolated existence. Simon would talk to me endlessly about what Japan was capable of and what we could achieve, as if I should automatically want to pursue the same goals as him. A wit and raconteur, he enjoyed nothing more than attempting to extract large sums of cash from record companies. He could charm his way out of the most difficult situations …

I had to find another, less commercial, way of working, which was why during the recording of Tin Drum [Japan’s final and best album] we kept Simon as far away from the studio as possible. We locked the door on him.’

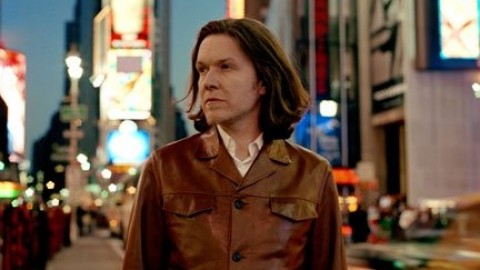

We are sitting in my room at the Mandarin Oriental hotel in New York, with its sweeping views across Central Park. The sky is clear and blue, but it is oppressively cold outside. Sylvian, who is 47, is dressed entirely in black. His long grey-brown hair hangs lankly, framing his face, and he has a thin stubble-beard. Beside us his young daughter Isabel, wearing headphones, sits patiently in front of a laptop. Later, I ask her if she has ever seen photographs of her father as a young man. ‘You know,’ he says to her, ‘when I had white hair.’ He turns to me. ‘I don’t think she liked them.’

Today, Sylvian lives in New Hampshire, in a former ashram that, when he bought it, was, he says, ‘held together by little more than string, glue and love’. His property, where he has his own studio, is ‘on the side of a mountain, buried deep in the woods’. There is, he says, ‘the most beautiful spirit about the place’.

His brother, Steve Jansen, who I met for coffee in London last week, recently spent a year with Sylvian at home in New Hampshire, working on a new album.

‘It is remote out there,’ he says. ‘You are 20 minutes from the nearest small town, Peterborough. Throughout his adult life Dave has shut himself off, with a partner, in quite an isolated situation. He doesn’t partake of the usual pleasures, shall we say. He never did, even when we were touring. Some frontmen can’t stand being at the centre of it all, and have to cultivate a persona even to get on stage. Dave shied away from meeting fans or enjoying being on the road with the band and the crew. He’s never really gone for a drink in the bar or out on the town. I can’t honestly say why. All I know is that in not doing those things, he gives himself a leverage that he needs.’

A leverage over others? ‘

Quite possibly. He has a way of viewing others at a distance and therefore controlling what he needs to control. It’s complicated. I’m not sure why he can’t relax in those situations.’

Jansen and I met at the offices of Opium Arts in west London, where Sylvian’s dedicated manager, Richard Chadwick, is based. It must be frustrating for Jansen, a talented musician in his own right, who is preparing to release a solo album in the autumn, to be defined by a group he left at the age of 22. But he showed no evident frustration as he talked about those years, about what went wrong and how he and the rest of the band receive almost no publishing royalties from sales of Japan’s back catalogue. ‘You’d go crazy if you spent your life thinking about what might have been,’ he says. ‘Yes, we could have been set up for life if we’d continued together for a bit longer, but I don’t dwell on it. I’m not bitter. After the band split, it took me several years to be able to connect with society … but if you want to be happy you find a way through all that. You find a way of coping.’

Also in the office that day was David Sylvian’s former partner, Yuka Fujii. Once a girlfriend of Mick Karn, who now lives in Cyprus, Fujii had contributed to the unease within the band by leaving Karn for Sylvian.

‘Being in the middle of all that was very difficult,’ says Jansen. ‘The tension back stage on tour was unbelievable. Mick has quite an ego on him. In those days he was very headstrong about what he wanted to do. He started to make plans for a solo album during the recording of Tin Drum, and Dave wasn’t happy about that. And the girlfriend problem set it right off between them. Mick never really got over those issues. I don’t think you can.’

The truth about Japan is that they found an audience too late, after they had decided to split, and when personal conflicts were becoming unbearable. They spent much of 1982, their most successful year, in a condition of hopeless belatedness, promoting old material that they wanted to be free from.

But at around this time Japan began, despite Sylvian’s distaste for the conventions of the business – the album, the tour, the promotion – to sell enough records to make the charts. Their most ambitious song, ‘Ghosts’, turned out also to be their most commercially successful, reaching number five in the spring of 1982.

I recall, mesmerised, watching Sylvian performing the song on Top of the Pops. He and the rest of the band – so still, so exquisitely cold and distant – were like nothing I’d seen before or since. As for the pared-down minimalism of the song itself, Napier-Bell calls ‘Ghosts’ the ‘most uncommercial song in the history of the music business to make the top 10’.

After ‘Ghosts’, Sylvian briefly became something of a teenage pin-up, ‘the most beautiful man in the world’, as he was called in a marketing stunt, a sobriquet he loathed. This, after all, was a time when girls liked boys who wore make-up and looked less like boys than, well, girls. It was a time when we all liked to dress up with arch ostentation and steal our mothers’ make-up. But it was a superficial time, and no one wishes to be reminded of the excesses of their youth.

‘I never really enjoyed our success,’ Sylvian said later as we continued our conversation by email. ‘I rarely partied hard. My sexual partners were few. During this period I remember spending much of my time alone, whether at home, in various modes of transport, or in hotel rooms around the globe.’

He concedes that his elaborate image was a kind of mask of disguise, behind which he could hide and through which he could be on stage and perform. ‘I realised that celebrity wasn’t for me. I’d lived in a glass cage of my own devising, had grown up in public to a large extent, and I simply wanted out. The notion of investing time in my celebrity was anathema to me … The periphery is the area I inhabit in every aspect of my life. I used to resent this and fight against it, often with disastrous results. But I accept it now.’

The son of a plasterer, David Sylvian was born in Beckenham, Kent, in 1958. He formed Japan, he says, as a means of escape – from home, from the low-toned mediocrity of ‘an environment that threatened to identify, classify, and therefore limit or suppress you. The pressures on my father to support the family were immense, or at least, at times, they felt that way to him. On one level, home was a very close-knit environment, and we relied on my mother very much. On another level, it was quite a frightening place, a very insensitive place. Quite brutal. I’m now very close to my parents. Whatever difficulties we had as a family have long since passed. But I always had a desire to get away, to escape and to try to nurture what I thought was missing from my home environment – aesthetics, a sense of beauty.’

Sylvian released his first solo album, Brilliant Trees, in 1984, a stark departure from the old Japan sound. I often look back on 1984 as one of the bleakest years of my life, a year when I finally emerged from the illusions of late adolescence to discover I’d spent two years in a kind of drifting, nebulous dreamtime. So, as friends left for university, I headed off in another direction – to the local dole office. And I still couldn’t play an instrument.

The soundtrack to my life during the quiet, sometimes distressing second half of that year was the seven songs of the introspective Brilliant Trees. During the recording of that album, Sylvian became addicted to cocaine and the album certainly has a disturbing, ethereal quality, in the world yet apart from it. ‘I had a sleeping disorder whereby I couldn’t stay conscious for more than four hours at a time, and I was looking for some medication to help with that,’ he says. ‘Cocaine gave me the drive I needed to keep going. In the end, I reached such a low with the drug that I knew I had to stop altogether, that I couldn’t go on living in a state of dependency.’

This was a period of intense self-questioning for Sylvian. Living an isolated life in London with Yuka Fujii, he began to experiment with meditation and eastern religion. Meanwhile, the rest of the band were struggling to establish themselves away from the control and influence of Sylvian, on whom they had always been dependent for guidance and to write material. In 1986, Sylvian, working with the likes of Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson, and the jazz musician Kenny Wheeler, released Gone to Earth (1986), which remains my favourite of his albums. This was followed by Secrets of the Beehive (1987), completing a loose trilogy of work that, though working within the form of the pop song, sought endlessly to subvert it.

He did not release another solo album until the disappointing Dead Bees on a Cake in 1999, though there were further collaborations with Fripp. Part of the reason for his long silence was the end of his relationship with Fujii. ‘I was completely numbed by the experience,’ he says. ‘I couldn’t write at all. It wasn’t even an option. The whole thing took me at least five years to work through, psychologically. I saw a psychiatrist; I needed help. I didn’t think I could get through it on my own … the feelings of guilt, unhappiness and grief.’

I met David Sylvian for the first time in 1991. I heard that Japan had reformed and returned to Virgin, but under a different name, Rain Tree Crow. Having graduated two years earlier I was making my way as a literary journalist and had long since accepted that growing up is also about growing out of the influences you once had; it is about taking down the old pop posters from the wall, putting away those records and CDs, and taking responsibility for who you are, in the present, and not who or what you want to be. Which is why, I guess, some time during the mid-Eighties I’d stopped bleaching my hair, stopped listening to Japan and David Sylvian and discovered in literature what I once sought from pop.

Yet here I was thinking all over again about Sylvian and the rest of Japan, tantalised, as they must have been, by the possibilities of their reunion. I called the arts editor of the European newspaper, the improbably named Derwent May.

Was he interested in an interview with David Sylvian?

‘David who?’ he said.

‘David Sylvian – he’s very good.’

‘Is he big in Europe?’

‘Yes, he’s huge,’ I lied.

‘OK,’ May said, without enthusiasm. ‘Let me have 800 words.’

I knew Sylvian, who was then 33, preferred to be interviewed in smart west London hotels, where he would be encountered smoking strong French cigarettes and drinking chilled water. And here he was, sitting before me in a suite at the Holland Park Hotel, smoking strong French cigarettes and drinking chilled water. In those days, he still looked recognisably like the David Sylvian of my imagination. Yet I could not look at him without seeing the young man he once was, so that I was simultaneously in the moment and yet outside it, pre-occupied by dreams of the past.

He spoke in controlled, measured sentences, with scarcely a trace of his old Beckenham accent, about his ‘spiritual journey’ and how music was a ‘process of self-discovery’. I was baffled that he did not speak about his brother or the rest of the band. He seemed troubled, unhappy even. I left our meeting feeling dissatisfied: thrilled finally to have met this courageous innovator, yet disappointed with the new album and the way he had spoken, dismissively, of Japan, describing their music as ‘hollow’. My 800 words remain unwritten.

Later, I discovered that Rain Tree Crow had ended as unhappily as Japan: in rancour and dispute. ‘When we discussed getting back together, we agreed that we would concentrate on the material without any of the old clashing of egos,’ the likeable Steve Jansen told me when we met for coffee. ‘We went into the project with a very positive attitude, and, for the first few months, spent in the south of France, everything went well and we had enough material for an album. But the budget was running low and the old tensions started to build.

Virgin had given us a chunk of money – some of it we lived off, but most of it went on recording the album. When the money ran out, Dave managed to raise some more from one of his publishing deals for extra mixing time. He suggested that he and I, because we’d always had similar ideas and approaches, should go into the studio and finish mixing the album, but without the other guys. I thought that was unfair. At that point, we fell out and had a row. Things were said, things that perhaps needed to be said, but had been buried for too long.’

Japan were no more. The brothers would not speak again for at least five years, during which time Sylvian moved to the US and married the poet-songwriter Ingrid Chavez, who first found a kind of fame as an acolyte of Prince.

One late summer evening in 2003, David Sylvian returned to London to play one night at the Royal Festival Hall. It was a sellout. By this time I seldom listened to his music any more, yet I went along to see him all the same. His hair was longer, his timbrous voice was much deeper, and he was accompanied on stage by his brother, Steve. It was an oddly moving occasion, not least because Sylvian’s audience had aged with him – all those neurotic boy outsiders now moving towards middle age together.

Sylvian was in town to showcase his new album, Blemish, released on his own label, Samadhisound, and recorded at his home studio in New Hampshire. Blemish is brave and uncompromising. Dense and sometimes inaccessible, it occupies an ambiguous space somewhere between hard, free-form experimental electronic music and the avant garde, and has revitalised my own and others interest in his work – which, judging from what I’ve heard of a new album he’s been working on with his brother, is moving in new and promising directions. Blemish can be listened to on many levels – but most notably as an anguished confession during which Sylvian grapples with the failure of his marriage to Chavez, with who he has two daughters. He told me that they are soon to divorce.

He recorded Blemish in just six weeks, and following a concentrated period of listening to his own back catalogue as he prepared one last compilation album for Virgin, Everything and Nothing. At the same time, he knew his marriage was collapsing, that the ‘years of domestic bliss, such as I had never experienced before’ were gone for ever.

‘The forms of the pop song had become too familiar to me,’ he says. ‘I felt creatively stifled. Working on Blemish was all about finding a new vocabulary; I had this great desire to eradicate the past. And I was dealing with emotions to do with my wife – feelings of bereavement and loss. Music was all I had to fall back on. At the end of the recording, I felt a sense of pure catharsis. I’d looked as deeply as I dared look at the side of myself that I’d prefer to keep hidden. It all sounds far more dramatic than it is, but the last few years have been very difficult to live through.’

That evening, at the Royal Festival Hall, as Sylvian sang of how ‘mine is an empty bed/she’s forgotten, I know’, his audience of dedicated fans listened respectfully, as they always do. But I sensed they weren’t really there to hear Blemish, but rather some of the old songs that had meant so much to them when they were young. Perhaps Sylvian knew this, too, because he began the second half of the evening by singing ‘The Other Side of Life’, from Quiet Life.

I’m not sure the cheer that followed was one of exhilaration or pure relief, but whatever it was you could have heard it from the top of the nearby Millennium Wheel. They loved him still, after all these years.

Jason Cowley is the author of the novel Unknown Pleasures (Faber). David Sylvian’s new album of personally commissioned remixes from Blemish, entitled The Good Son vs the Only Daughter, is available from www.samadhisound.com and HMV stores; further information at www.davidsylvian.com

Original article on theguardian.com