David Gavan talks to David Sylvian about why there’s no ‘I’ in Manofon . . .

Copyright: The Quietus, October 12th, 2009 13:39

Since the late seventies, when he raged about “identity” on Japan’s debut album, Adolescent Sex, David Sylvian has proven himself to be a rootless character. As the band’s glam rock inventiveness morphed into synth-led sophistication, they became unwilling avatars of the New Romantic movement, only to split in 1982. Uninspired by the fame he had sought, Sylvian brushed himself down and embarked on a more inward journey, something that may have alienated less spiritually-minded members of his fan base.

Fortunately, his solo offerings have studiously avoided self- indulgence — from jazz-inspired existentialism (on 1984’s luminous Brilliant Trees) to meandering improvised drone with Can bassist Holger Czukay (1988’s Plight and Premonition and 1989’s Flux and Mutability) on to blistering rock funk with Robert Fripp (1993’s The First Day). Even amid his avant garde explorations, Sylvian’s pop instincts have always prevented him from throwing the rock rulebook out of the window, despite a tendency to balance it on the outside ledge.

After the uncharacteristically treacly art pop of 1999’s Dead Bees on a Cake — a sprawling disc replete with the joys of emotional and spiritual fulfillment — Sylvian provided a salutary jolt withBlemish in 2003. A starkly improvised set, the album boasted three sternly minimalist collaborations with the late, lauded improv guitarist Derek Bailey. Beyond the music, many listeners were struck by the disc’s emotional openness and lyrical verve, as the singer depicted his unravelling marriage to former Prince associate Ingrid Chavez. Once Sylvian learned how to integrate his voice with Bailey’s improvised pieces, he knew he wanted to take things further.

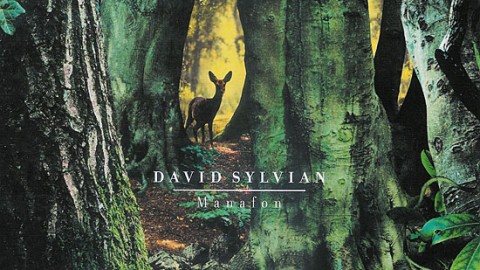

His most recent offering, Manafon (which takes its name from the village where Welsh poet and clergyman RS Thomas lived and worked), continues down the same radical path. It features strikingly committed improvised performances from electroacoustic luminaries such as Keith Rowe and his former AMM partner, pianist John Tilbury; members of Viennese minimalists Polwechsel; and onkyo musicians Toshimaru Nakamura, Tetuzi Akiyama and Sachiko M. The disc also features performances from esteemed sonic explorer Christian Fennesz. There are no drums to nail things down, and the melodic lines are provided by Sylvian’s unexpectedly emotive voice as his pared-down lyrics sketch a series of third-person narratives. As he sings in the opening track, ‘Small Metal Gods’ (the only first person lyric), this is a new frontier for Sylvian, and the contours of what first seems like a snowbound sonic landscape become more visible with each subsequent listen.

There are also some intriguing contrasts to enjoy: between improvisation and composition, technology and organic instrumentation, and — most noticeably — between austere musical discipline and vocal warmth.

David Sylvian: “I’d say there was warmth in the musical arrangements too, but it’s minimal in its usage. Essentially, any given musical ensemble is trying to work with a dramatic economy of means; so nobody is picking up or developing melodic lines. But i’m working against that aesthetic, taking what I hear as a cue to elaborate on a line, or using a certain sound as punctuation to end or begin another line.”

Meanwhile, the lyrics — Beckettian in their economy — offer a compelling mixture of irony and pathos, combining what Sylvian calls “the preciously poetic” and the “clunkily prosaic”.

In the archly titled ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’, which essays the plight of a writer who sacrifices his humanity to literary ambition, Sylvian slyly takes the piss, even while conveying compassion:

“Here we are then, here we are / notes from a suicide / And he will never ever be / The greatest living Englishman . . . His aspirations visited him nightly / And amounted to so little / Too much self in his writing . . . He had ideas above his station . . .”

Memories of Beckett’s failed writer, Krapp, bounce around the study walls, while the “Too much self in his writing” line sounds like a coded reference to Sylvian’s celebrated lyrical reticence. “Yes, the album certainly has elements of Beckett for me as well. And, in a sense, looking at the life of RS Thomas, he becomes something like a character in a Beckett work. It has that irony and humour, and a lost sense of purpose, if you will. I realised later how those aspects attracted me to the character of RS Thomas: that ironic dichotomy of a man of faith who questions that faith. As for the lyrics’ application to me, I don’t have too much to say about that. I think the ambiguities work in favour of the piece.”

Certainly, questions of meaning and purpose characterise Sylvian’s career. On Japan’s debut recording, ‘Adolescent Sex’, Sylvian criticised TV networks for broadcasting “blasphemy with a smile”; on 1992’s shockingly moving ‘Forbidden Colours’ he pondered his relationship with an elusive deity. When I mention the New Age spiritual pick ‘n’ mix that has usurped organized religion, he laughs at the idea, but it’s clear he has already considered this. My implication that the mixing of various spiritual disciplines (Zen Buddhism and Hinduism in his case) would be futile in the absence of a benevolent maker, is an issue he wisely chooses not to pursue.

“I don’t think there’s any harm in that approach”, he reasons. “It’s experiential and you absorb a certain amount in your search for something that works for you. I think you can take it too far. It’s better to embrace a discipline and go with it one hundred percent. But there are tangible results to be had if you find the right discipline,” he asserts.

What emerges from speaking with Sylvian about such matters is the idea that all the great religions provide a roadmap to the same destination, and that one’s chosen route depends on personal inclination.

“Absolutely, I’ve had certain [spiritual] experiences that have been life-changing, so it’s impossible to do away with notions of a greater sense of reality.”

However — like RS Thomas, whose poetry sometimes appeared to undercut his faith in God — Sylvian feels moved to question his spiritual practice on Manafon. Not least on ‘Small Metal Gods’, which berates deities that have “refused my prayers for the umpteenth time / So I’m evening up the score.”

“I reached a breaking point where I wasn’t understanding the lessons that were being given me”, he explains. “This kept me treading water for some years, so I just wanted to express that frustration without any fear of repercussions. Being able to write about it was the first step. The piece is a rather childish stamping of the foot: “This isn’t good enough — so fuck off!” But it’s liberating in that way, because there’s so much respect for the hierarchies and the discipline itself. But that doesn’t put the cap on the whole thing. It’s me telling myself that I can eradicate anything that doesn’t work — even if it’s an entire belief system. I decided to put my faith in the creative spirit and see where it takes me.”

This runs counter to some of the ‘Sylvian Dumps False Gods’ shtick to be found in recent press reports. The depiction of the man as a latterday hermit hiding out in New England woodland hardly rings true. In conversation, he is articulate, open-minded and much given to laughter.

Nevertheless, for Sylvian, Manafon the place clearly represents the artistic imagination: a kind of metaphysical Milk Wood.

His continuing sense of existential doubt, as showcased in Japan’s biggest hit, ‘Ghosts’, may explain the feeling of suspense that pervades this work. Sometimes, amid the stripped-back sounds, there’s a sense of a creaking shipwreck run aground and ready to fall. The singer never once raises his voice, though you feel he’s about to. That’s unlikely, considering the lid that’s been kept on such outré emotions as anger by Sylvian since the early 80s. So much so that I wonder if he’s trying to cordon off this aspect to his character.

“Well, in the early days, there was a fair bit of anger, and that needed to be expressed. But as you get older, that gets digested and surfaces in entirely different ways. There can be microbeats in the body of a composition that express anger so much more succinctly than a power chord, or an enraged vocal. I mean, ‘The Only Daughter’ (on Blemish) is a piece of murderous feeling. It could be describing a murder that’s already taken place.”

Nevertheless, Blemish is a surprisingly recrimination-free affair as divorce albums go. The title track even contains the lines: “The trouble is / It’s impossible to know / Who’s right and who’s wrong.” I ask him if such even-handedness isn’t pathologically forgiving?

When he stops laughing, Sylvian adopts the tone of a benevolent persuader: “Yeah, but it’s possible to see through the anger and know that the degree of hurt you’re experiencing is colouring everything. So there IS no wrong or right at the end of it,” he says with mock exasperation. “That’s obviously the case. It takes two to make a relationship and there are different needs in different people. I couldn’t take myself so seriously as to think that my viewpoint was the only one.”

As he says, Sylvian is simply a more mature character than the mascara-blinded Bowie freak who felt “everything would be over” if he couldn’t escape South London’s unlovely Sydenham. Naturally, this maturity has seeped into his music and the improv approach has clearly liberated (a word he uses often) him from his notorious perfectionism.

“With Blemish and Manafon there was an immediacy to the process. Recording was very instantaneous. You put something improvised on the guitar down on the hard drive and immediately responded to that lyrically. Within a couple of hours, you have a complete set of lyrics and a melodic line. So I’d record that on the spot, which allows me to be less cautious about what’s revealed. On Manafon, I often didn’t listen back to the improvisations until a much later date [he subsequently sang and played guitar over them, but resisted the temptation to reconfigure the performances], so there was a freshness.”

“Less cautious” is one thing, but Sylvian’s no fool and indecent exposure of the psyche just isn’t his style. Also, there’s an important distinction between self-expression and self-mutilation; something he’s clearly conscious of. Instead, he will sing in the third person about lack of human warmth or isolation which, ironically, makes for Sylvian’s most intimate recordings to date.

“Now, maybe, there are no barriers, no reticence on my part about what needs to be addressed. And maybe”, he says ruefully, “I’ve placed a number of pieces in the third person to let me deal with certain subject matter. Because it may be uncomfortable in the third person: but in the first person it would be unbearable!”

So despite his personal and spiritual travails (or because of them, if you like your artists to be tortured), we have a creatively revitalized David Sylvian. He’s even thinking of touring Manafon.

This would make for an unmissable live experience: an emotionally engaged Sylvian interpreting this extraordinary album with a newly-assembled band.

There’s a hearty peal of laughter when I suggest that, in a parallel universe, Manafon would be on pop radio rotation.

“I’ll take your word for that”, he says.

“I’ve had a notion over the years of where pop could be going, but everybody tends to disagree. But in a ‘parallel universe’? Maybe.”

original article on thequietus.com