Interesting article as published online on Flux To Form. Author unknown.

1. Evolve and experiment, always.

David Sylvian’s protean career of forty years has encompassed an extensive variety of genres, from his cornerstones of art-pop/rock, downtempo, ambient and experimental electronica, to dabblings in prog-rock, avant-jazz and world music. The resulting mélange of styles that comprise his impressive oeuvre are indicative of a creative yet restless spirit; an admirable yearning to keep pushing his own boundaries, and to continue evolving as an artist. Each new album or project seems to entail a subtle reinvention of the self. To get too comfortable would be creative suicide.

Over the years, David’s evolution in style has brought him continuously closer to the periphery of mainstream music. While some fans – particularly those whose fondest memories of David are with his former band, Japan – see this as an unwelcome transmogrification, it’s undeniable that his desire to experiment is brave. Fortunately, satisfying the Vox populi has never seemed to be much of a concern to David. For more sapient fans, his most recent albums are rich in nuanced beauty; expressive and atmospheric.

Would it be easier for David if he continued to produce albums in the style of his much-loved late 80s masterworks, such as Gone to Earth and Secrets of the Beehive? Possibly, but that’s not the point. David’s art is an authentic expression of his inscapes, and as those inscapes change, so does the manner in which they are reflected in his work. To intentionally recreate the atmosphere of works that presumably no longer resonate with his inner self would be a compromise of his artistic integrity. Whatever might come next for David will undoubtedly reflect whatever he’s driven to express in that moment in time.

2. Less is More.

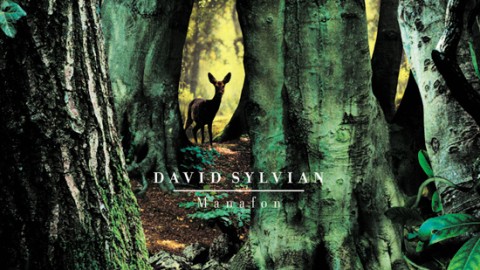

Minimalist music often poses a challenge to listeners because it commands one’s full attention and intent focus to be fully appreciated. Done well though, the results can be striking and delicately beautiful. Manafon, David’s most recent studio album, achieves these results.

David presumably is well aware that his greatest strength musically lies in his singing, and on Manafon, that preternaturally stunning voice takes centre stage, with little adornment. There’s an element of existential nudity imbued in such a stripped back delivery, and it’s that very starkness that gives songs such as ‘Small Metal Gods’, ‘Random acts of senseless violence’ and ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’ their power. Bravery through vulnerability.

No song from Manafon better encapsulates the “Less is more” mentality better than ‘125 Spheres’, though: clocking in at a mere 29 seconds and with lyrics consisting of only 20 words, it’s an exercise in brevity that nonetheless packs one hell of a punch, leaving the listener wondering exactly what it was they just listened to. That such a song, as well as Manafon’s much longer tracks, have such an impact on the listener despite their relative lack of instrumentation, is proof that if the foundation of your art is strong enough, it doesn’t need excessive ornamentation.

3. Embrace and explore your spirituality.

David’s syncretistic spiritual beliefs have been an influence on his art since the mid-80s. Though not explicitly religious in a traditional sense, David’s personal search for meaning has most notably led him to the Buddhist and Hindu faiths (particularly Zen Buddhism, and the Vedanta school of thought in Hinduism), with explorations in Shintoism, Sufism, Shamanism, Gnostic Christianity, the Kabbalah, esotericism, and the teachings of George Gurdjieff along the way. These explorations not only speak to David’s intellectual and philosophical curiosity, but are indicative of a receptive mind and spirit unencumbered by solipsism.

Though there was evidence of David’s philosophical inclinations in many of his earlier works, the late 90s and early 00s marked an epoch in his spiritual quest, drawing on his immersion in Vedanta, the teachings of the Hindu mystic Mother Meera, and devotion to his guru, Mata Amritanandamayi (Amma). Numerous songs from 1999’s Dead Bees on a Cake were inspired by this turning point in his life: most obviously ‘Praise (Pratah Smarami)’, sung in Sanskirt by his former guru Shree Maa, as well as ‘Krishna Blue’, ‘I Surrender’ and ‘Thalheim’ (the latter referring to the German village where David received a darshan from Mother Meera in the early 90s). Several additional non-album or live-only tracks also reflect this spiritual milieu, and arguably even more pronouncedly: the hymn-like ‘Bhajan’, written in response to David’s first meeting with Shree Maa; the lyrically self-explanatory ‘Blue Skinned Gods’; and ‘The Song Which Gives the Key to Perfection’, taken from a Hindu text, the Devi Mahatmya, and sung by David himself in its original Sanskrit.

You’d be forgiven for assuming from this significant body of work that David must be a devout and practicing Hindu, but by his own admission his beliefs are more a hybrid of both Hinduism and Buddhism. “I like the clarity of Buddhism and I also like the devotional aspect of Hinduism. And my own practice somehow embraces both of those disciplines,” he explained to a Canadian newspaper in 1999, adding in another interview the next year that his guru, Amma, had taught him that “it is possible to embrace the godless beliefs of Buddhism as well as the world populated by numerous gods.” Such a teaching is immeasurably comforting for those who find that no single school of faith resonates with them wholly. In David’s work, elements of numerous religions and spiritual styles not only coexist, but amalgamate into a fusion of faiths that is uniquely his: a testament to the esemplastic power of David’s creative and perspicacious mind.

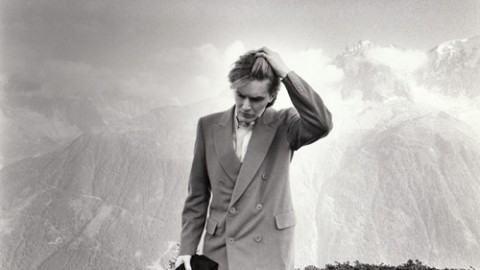

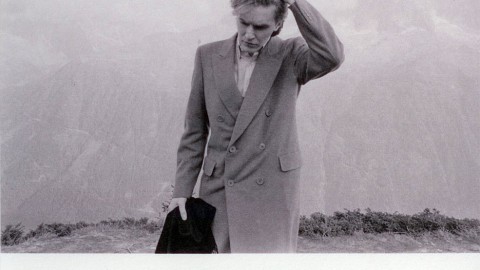

4. Know how to pick the right collaborators.

Since the onset of his solo career, David has always had a keen understanding of the type of musician whose talents best compliment his own. Contrary to the public persona of an aloof and introverted lone wolf, David has in fact regularly collaborated with other artists, in addition to employing a large number of collaborators for his own albums. His work with Robert Fripp (The First Day, and live album Damage) and Holger Czukay (Plight & Premonition and Flux + Mutability) are two drastically different – but equally brilliant – collaborative efforts that allowed David to experiment with and showcase his aptitude for prog-rock and ambient styles, respectively. Personality and an emotional connection are clearly important factors too, especially when it comes to repeated collaborations. Life-long friend Ryuichi Sakamoto, whom David has regularly worked with from the early 80s right up until just last year, is an obvious example.

When it comes to the personnel David recruits for his own albums, one gets the impression that part of the secret to their successful work together lies in David’s trust in and respect for those he works with. While he remains a sagacious overseer, he gives his collaborators the opportunity to put their own unique spin on the material, and this open-mindedness not only gives strength to the artists’ personal connections, but stimulates the creativity of all involved.

David Sylvian and Robert Fripp.

5. Embrace life wholly – the good and the bad.

“I’m not a negative person; I’m a very optimistic person. I highlighted the darker side of life in my work because I think that’s the way to get people to reflect on the lighter side.”

– David Sylvian

For me personally, one of the most inspiring things about David is his insightfulness, and his ability to reconcile both the positive and negative aspects of life. He’s not naive, or oblivious to life’s struggles, but nor is he completely nihilistic. For many years, a recurring theme in David’s personal philosophy has been to embrace all experiences wholly and indiscriminately: acceptance of whatever life brings, even if what it brings is unpleasant. “The greatest kind of happiness is a kind of peace with yourself, coming to terms with yourself whatever the condition is,” David once said in a magazine interview. “Not a neutral calm, or a mindless calm, no. I think that true peace can only come through understanding.” It’s a philosophy that sounds reasonable and “simple” enough on the surface, but that necessitates tremendous mental and emotional strength to genuinely uphold. No doubt this belief has been enforced by David’s spiritual explorations, but the concept itself is secular, and we could all benefit from embracing it.

From Time Spent, a short film made in the late 90s with his then-wife Ingrid Chavez, comes what is perhaps the most astute and inspiring explanation of David’s philosophy:

“I view the experiences I encounter in life as opportunities from which to learn and to grow. There is a view, which is not easily grasped on a moment to moment basis, that whatever you are doing, whatever your predicament, however much you are suffering, it is all entirely perfect: it is as it should be. Obviously this is hard to acknowledge, particularly at certain periods in life. But just the remembrance of this fact could be immeasurably invigorating and allow for perspective to be glimpsed or perceived, which might not otherwise have been possible, so immersed in our personal experiences as we tend to be. I take this notion to mean we are given the lessons most pertinent to our growth: we are not given more than we can handle, and that if we recognise this fact in the midst of the experience, we can learn from the most difficult of our circumstances and move on.”

6. Never compromise your integrity.

“I’m stubborn, idealistic, uncompromising. There’s an underlying aesthetic at work that’s been my guiding principle for many a decade but it evolves, matures, it becomes more refined as time goes by.”

– David Sylvian

Since as far back as the early 80s, as frontman of Japan, David has stringently upheld the moral values governing his art. Like any artist, reaching an audience has always been important, but commercial success, especially at the cost of his integrity, has not: his creative goals have never been fame, money, or elevation of the ego. Self-expression, above all else, has been David’s raison d’être from the onset of his career, even if it means limiting his audience or his commercial viability. To David, success attained by compromising one’s value’s is not success worth having.

Such integrity is also evident in David’s personal conduct towards others, and dates back to the very first hours of his musical career, at the tender age of seventeen. After impressing Japan’s soon-to-be manager Simon Napier-Bell so much with his audition that Napier-Bell offered to sign him on the spot, David agreed only on the condition that his bandmates be included as well, despite Napier-Bell wanting to sign him as a solo artist. What degree of moral fortitude must one possess to take such a bold risk, out of loyalty to one’s friends? Mick [Karn], Steve [Jansen], Richard [Barbieri] and Rob [Dean] must undoubtedly have been grateful for this audacious move, though unfortunately less so when it came to reforming Japan in 1990 under the name Rain Tree Crow: a further testament to David’s integrity in the artistic sense, in not wishing for the new material to ride on Japan’s quondam success.

There’s always been an element of sacrifice in David’s desire to stick to his principles. Arguably, Rain Tree Crow would have been more successful both commercially and financially – and the project may even have continued – if David had been as willing to recant, at the last minute, their earlier agreement to disown the name “Japan” as his bandmates were. However, such acquiescence would have been in direct conflict with not only David’s overarching moral code, but the sentiment behind the project’s very existence.

It would be easy to get sidetracked by the thought of what opportunities and successes such highly upheld principles may have quashed, but to the man possessing them, such sacrifices are worthwhile. David’s integrity may have prevented him from achieving as much mainstream success as his work deserves, but it’s also the reason why he’s one of the most admirable musicians of the past forty years.

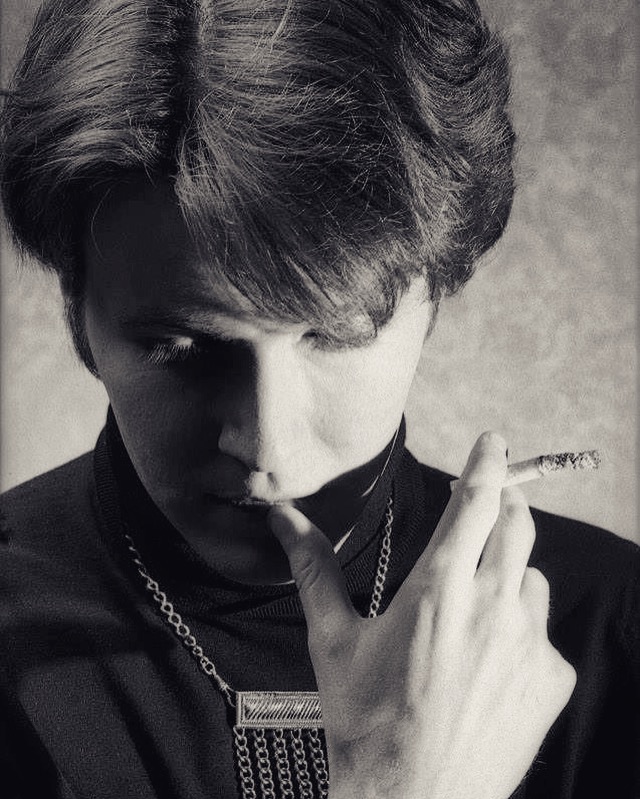

7. Pay attention to the aesthetic of the art, not the self.

While Japan was a visually striking group and much attention in particular was paid to David’s sartorial style and personal appearance, by the band’s final days David was becoming increasingly disillusioned with his own aesthetic. The visage that had initially been an escape from his dreary working class roots now needed to be escaped from, especially as the motivations for his art became clearer to himself. Being questioned about his make-up routine for teen magazines bordered on insult, and being lauded by the British tabloids as “The Most Beautiful Man in the World” was not conducive to being taken seriously as a musician and songwriter.

So, the work of art became the artist himself: the energy once channeled into his personal style was redirected towards his photography, and just as importantly, into the visual presentation of his records and books.

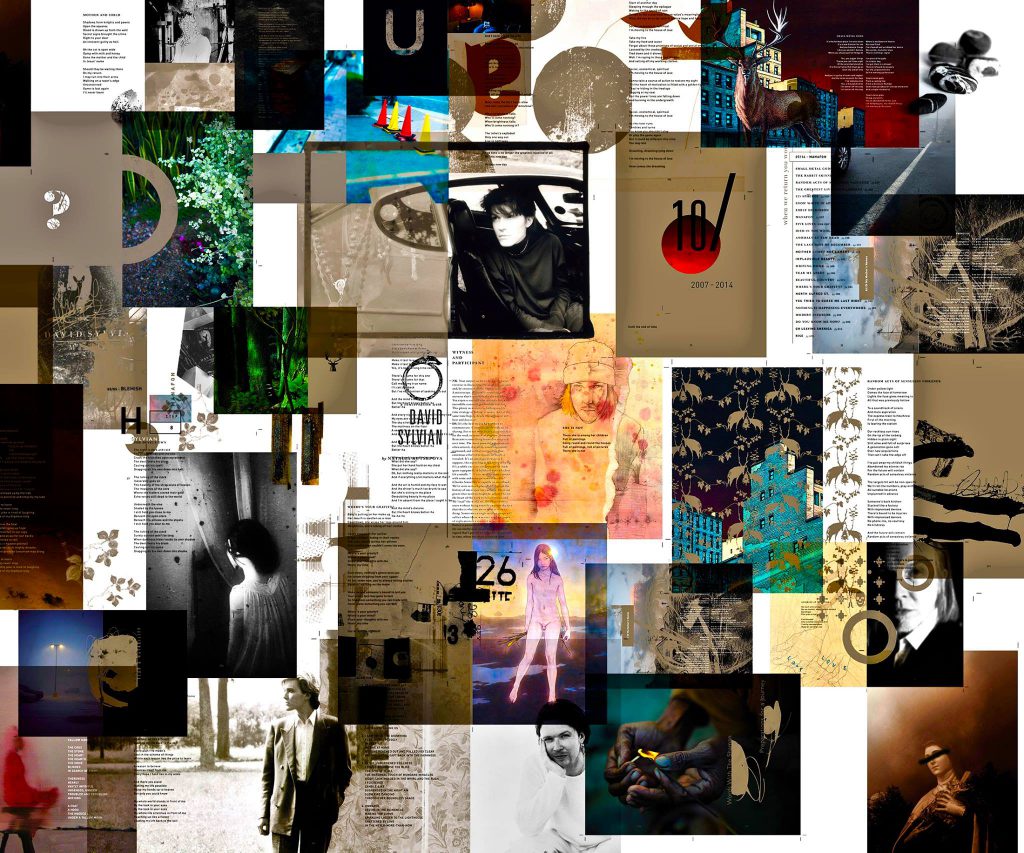

David has not appeared on the cover of one of his own studio albums since his 1984 debut, Brilliant Trees, instead working with a range of talented visual artists whose work clearly resonates with David on an emotional level. There’s always something incredibly striking about the artwork David chooses to accompany his music, and it is often imbued with an ethereal quality, whether in the abstract paintings and drawings of Russell Mills (Gone to Earth) and Shinya Fujiwara (Dead Bees on a Cake), or the delicate, somewhat heartrending illustrations of Atsushi Fukui (Blemish) and George Bolster (Died in the Wool). Though the artworks themselves are obtained from or commissioned by third parties, David still always remains in control of the overall aesthetic, acting as his own art director.

David’s interest in the visual aspect of his work is most evident in his book of writings, Hypergraphia. Working with friend and designer Chris Biggs, the lavishly illustrated 600+ page volume is an amalgam of a poetry book and a coffee table art tome. David’s own image is used very sparingly, with the bulk of the imagery being a combination of his photography and curated artworks from others. The result is a stunning collectible that perfectly compliments the beauty of David’s music and lyrics, and proof that a striking aesthetic can enhance a work without overpowering it.

8. Value your own privacy.

David has always been an intensely private person. While one could easily theorise that his desire for privacy reflects of fear of vulnerability, it’s also entirely probable that David’s tight leash on his personal life is a means of ensuring that his creative work speaks for itself, without unnecessary added context. What David does share of his private life in interviews is often shared for the purpose of clarifying his art, or to express ideas that his work already does, in more detail. His respect for the privacy of others as well takes salacious gossip off the table, and a lack of ego negates the need to broadcast irrelevant details of his life for the sake of public interest or for attention. Such restraint is an increasing rarity in our current Age of Oversharing, and for that reason, David’s eschewing of such indulgences is all the more admirable.

9. Live in the present.

“I don’t have any personal desire or need to look back. I carry within me what I need to move forward.”

– David Sylvian

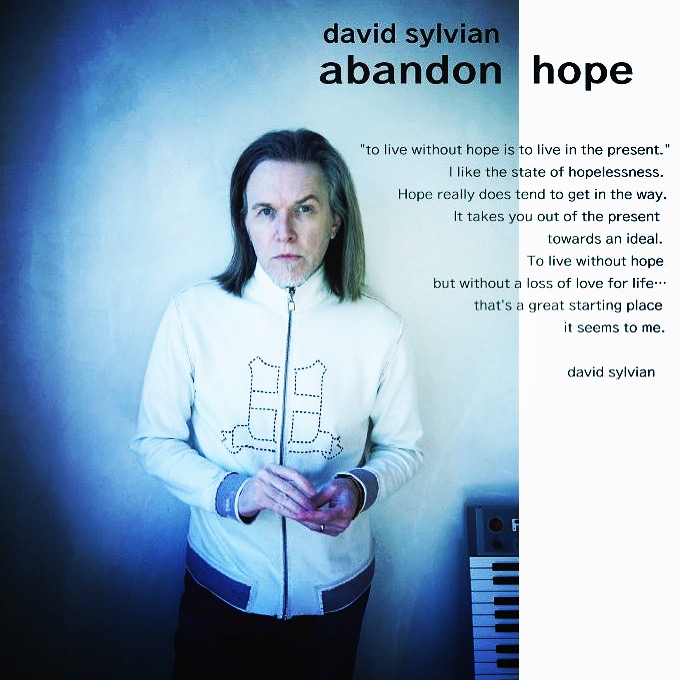

Far from the nostalgia he professed to be drowning in on 1984’s Brilliant Trees, David’s personal philosophy has long been to embrace the present, rather than either the future or the past. Recent interviews paint a portrait of a man becoming increasingly more self-assured and accepting of his circumstances, even if still not entirely comfortable in his own skin. “I didn’t feel at ease when young, but then I don’t feel at ease now for entirely different reasons. I am surer of myself. I know what I’ve got to offer,” David professed in a 2010 Q&A. It’s an uneasy form of acceptance, one that almost hints at resignation, but that nonetheless can also be seen as empowering. Focusing all of one’s energy on the present is a means of taking control, as the present is the only temporal mode which one can control: the past can’t be controlled because it’s already happened, and the future can’t be controlled because it’s not yet arrived.

It’s important to note that David’s rejection of both the past and future in this sense is not a reflection of a negative attitude towards either, but born of a desire to make the most of the present, untainted by either regret or expectation. David talks of living without hope, but more importantly, without a loss of love for life. That’s a great starting place it seems to me, too.

10. Stay humble.

If David Sylvian were conceited, it’s fair to say he’d have a lot of reasons to be. Fortunately though, that’s far from the case: David’s humility is in fact one of his most defining traits, as well as one of his most endearing. It’s born of a combination of quiet self-assurance and a genuine lack of ego, and manifests itself in both his personal demeanour and his approach to marketing his work. Attention-seeking is a foreign concept. David is well aware that his work speaks for itself: we can easily recognise its brilliance without him having to point it out.

To further attempt to elaborate on the origins of David’s humility would be fruitless: it simply is. It’s an ingrained aspect of his personality, even if he does also take conscious measures to remain grounded.

David Sylvian really is one of the few truly enlightened artists of our time: a man of tremendous integrity, humility, bravery and insight. Here’s to him, on his 60th birthday – and may there be many more to come.

Flux to Form