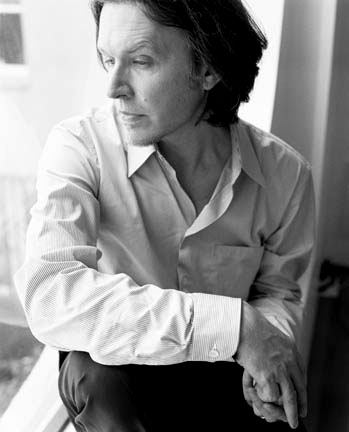

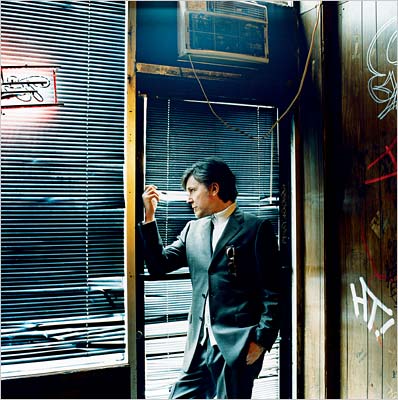

An interview with David Sylvian by Jason Cowley

In March 2005, the journalist and literary critic Jason Cowley travelled to New York to meet David for an article published in the Observer on 10 April. Their conversation continued over email.

JASON COWLEY: Why did you set up your own label?

DAVID SYLVIAN: I had become increasingly frustrated with Virgin [to whom he had been attached since 1980, first as part of Japan and then as a solo artist]. There was enthusiasm for my work from one or two people in the higher echelons of the company but there was no carry through. They were happy to get the albums but they wouldn’t know what to do with them. In the end, I felt that they really couldn’t care less if I produced any new work or not. What they wanted from me were compilations, which is what I ended up doing for about a year and a half. In truth, I agreed to do the compilations thinking they might let me back in the studio at some point. I was contractually obliged to put together a compilation but I managed to put them off and keep producing new work, which interested me more. So I went through the motions of producing compilations, as well as a re-mix of a live album, but it was a bad period. I felt creatively stifled. I was dying to start over again, but there was no support from the company. We finally managed to part ways with Virgin, and that was a release, on both sides. I’d just moved from California to New Hampshire and started to build my own studio complex there, trying to become more self-sufficient. I knew with the way the industry was moving that it wasn’t really going to be supportive of the kind of work I wanted to produce. I thought the best thing to do was to become as self-sufficient as possible and start from there, and see how things developed. It took about a year to build the studio. My brother [Steve Jansen] came over, and lived with me for about a year with his family. We started writing together…

JC: But then something happened. You stopped writing with Steve and took time out to make Blemish, perhaps the boldest and most uncompromising album you have ever made. Tell me a little about what led to the creation of Blemish?

DS: Blemish took only six weeks to make. I knew it would be described in the industry as a difficult album, which is why I decided to put it out over the internet. I thought: we’ll create a website, we’ll put it out without any distribution, and those people who are interested will find it. But the first reviews that appeared were so promising – they generated an awful lot of interest. From there, distributors came on board and wanted to be a part of it, and so the notion of a label began to grow. In truth, we were struggling to keep up with everything that was happening. But it was a gratifying struggle, because we were able to do deals on our own terms, and things were just evolving beautifully. At the end of this period we had a label, we had distribution, and everything seemed to be set up for the future. It’s now very gratifying to have a label and to be able to offer a platform to artists we admire, such as Harold Budd.

JC: I was impressed and moved by Budd’s release on Samadhisound, Avalon Sutra. He has said it is to be his final album – and these pieces of music, so fragile and full of longing, convey a sense of last things, of an artist coming to the end of something. When did you first hear them?

DS: Amazingly, I first heard the album in 2001, when I tried to help Harold find a deal for that album. Everyone turned it down. I finally met Harold for the first time in 2003 in LA, and offered to put out the album on our label. I think that period of refusal of some of his best work may have had something to do with his desire to call it quits at this point in time.

JC: How does it feel no longer to be with a major label? Is it liberation or loss?

DS: When I was in Japan, Simon [Napier-Bell, the band’s manager], would talk to me endlessly about what we were capable of and what we could achieve, as if I should automatically want to pursue the same goals as him. A wit and raconteur, he enjoyed nothing more than attempting to extract large sums of money from record companies…. He could charm his way out of the most difficult situations. I had to find another, less commercial way of working, which was why during the recording of Tin Drum [Japan’s fifth and final album] we kept Simon as far away from the studio as possible. Simon wished for me to see the industry through his eyes. He manipulated because manipulation was more entertaining from his perspective than a more passive (he would argue less creative) form of management and while this was quite an education, once I’d been given room to breathe, to gauge the situation, to size up the music business for myself, I realised that I could make it work for me in ways devoid of cynicism and crass exploitation, and that there were potentially greater returns in establishing relationships in the industry based on trust (I had a particularly long standing and productive relationship with Simon Draper at Virgin lasting almost two decades, a rare thing in music industry in the late 20th century) rather than taking the money and running. From the 1980s onward I never spoke of compromise and consequently compromise was never asked of me.

JC: I saw you perform Blemish at Festival Hall, in London, in the summer of 2003.Your audience listened respectfully, as they always do. But I remember at the start of the second half of the show, when you began by singing one of your old songs, The Other Side of Life, from Quiet Life, there was a huge cheer. It was so loud that you could have heard it from the top of the Millennium Wheel.

DS: It was probably a cheer of relief [we both laugh]. Blemish is an album that people have to work at. That people are prepared to do just that, to spend some time getting to grips with it – well, that’s an act of true generosity on their part.

JC: What do you think of the remix album, The Good Son vs The Only Daughter?

DS: I’m happy with it. Remix albums are, in general, only ever moderately successful: the person commissioned to do the remix would generally prefer to be working on his own material than being paid to work on someone else’s. In this instance, the remix gave us an opportunity to build relationships with artists like Akira [Rabelais] and Burnt [Friedman] that could lead to future collaborations. It gave us a chance to discover if we spoke the same language, if you like.

JC: To listen to Blemish is to discover an artist engaged in the complicated process of remaking himself. I was shocked when I first heard it. It sounded like nothing you had done before.

DS: When I began work on Blemish I had an incredible desire to eradicate the past and to find a whole new vocabulary for myself. At first, you are working from pure intuition. You are not sure where you are going; later, you begin to understand where the vocabulary is leading you and how to make it speak for you in a more profound way.

JC: The form of the pop song no longer interested you?

DS: For me those old forms reached a natural end – or shall I say their pinnacle – with Dead Bees on a Cake. Without the benefit of having to face my catalogue as I had to when putting together those compilation albums [for Virgin], I would never have been able to make such a radical break. In the end, I was too familiar with my own material. I’d toured with it, I knew it too well. I was happy to put it to rest and never face it again. I still enjoy the challenge of writing a well-structured pop song, but the stimulus for doing so usually comes from outside – someone will offer me a project or will offer to collaborate or give me a song to write a lyric to.

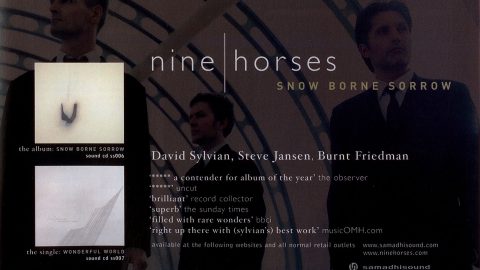

JC: You are in the process of completing an album with Steve Jansen and Burnt Freidman. I’ve heard the title track, Snow-borne Sorrow: much more accessible than Blemish but still bold and innovative and rather beautiful. How did this come about?

DS: Steve and I had been working on a project, and I’d also been working on another a project with Burnt. From there, the two projects just came together in the most natural way, and began to develop into something very impressive. The project will incorporate some of the strongest material I’ve ever written with Steve – that’s for sure, some really beautiful pieces. It’s a very confessional album. It has that same confessional edge as Blemish had and some very powerful and emotional qualities to it. The structures are rather repetitive, similar to Blemish, but, yes, far more accessible. But I’m looking forward to putting this one to bed and moving on. At times the speed at which I work causes me great frustration…so many other ideas to pursue.

JC: How comfortable are you about writing so nakedly of your own emotional experiences? Blemish can be listened to on many levels – but most notably and affectingly as an anguished confession, a tortured expression of interiority. One has a powerful sense of you grappling with feelings of regret and loss arising from the failure of your marriage to Ingrid. I felt your first solo album, Brilliant Trees, conveyed a similar sense of bewilderment and longing, but without the same intensity of feeling.

DS: The work I find the most gratifying is the work in which I’m most revealed in a way. When I was writing Blemish I was still in the midst of a difficult emotional experience. I wasn’t in a comfortable position from where I could look back … I didn’t know how to handle the emotional side of things. Once I got into the studio and closed the studio door, I felt a certain sense of safety, of liberty, to deal with the emotions, emotions that were primarily negative and all to do with my relationship with my wife. I wanted to delve far deeper into them than I would in daily life. How far can you go with that sort of feeling and where does it lead you? At the same time, I’m delving into something that one should be wary of delving into, because you don’t know how readily you will be able to re-surface from it at the end of the day. There was a sort of trepidation involved.

JC: Were you listening to other musicians at this time as part of your struggle to find a new way of expression and to make it new, as the modernists used to say?

DS: I went back to listen to artists I’d been listening to for decades – artists like Nick Drake, those evergreen artists you go back to decade after decade and still find a kernel of emotional truth in their work – but it wasn’t there for me anymore. The old emotional tug had gone. It was as if the whole language of the pop song was no longer valid. You cease to engage in the emotional content of the song because the form is too safe. Or perhaps the whole requirement of pop music is that it doesn’t provoke too much; it’s not designed to be provocative or unsettling. Yet I had these emotions to which I wanted to give voice. How to do that? How to make what you are doing relevant to now? All I knew was that I had to move on from these traditional structures – forms with which I’d been working for decades.

JC: The process you were going through sounds very painful, in every sense. Had you ever experienced anything like this before: the acute self-questioning, I mean, and the experience of deep loss – as well as the desire to remake yourself, artistically?

DS: I went through something similar in the late Eighties, at the end of a very important personal relationship [with Yuka Fujii]. I was completely numbed by that experience. I couldn’t write about it at all. It wasn’t even an option. The whole thing took me at least five years to work through, psychologically. I saw a psychiatrist; I needed help to get through it. I don’t think I could have got through it on my own, the feeling of guilt, unhappiness and grief were too great. When someone dies you have the actual physical loss of that person. But when an important relationship ends that person is still present in your life to some degree, and that confuses the issue enormously. At least, it did for me. It took me a long time to see my way through it.

JC: And now you are going through a divorce… the end of something important, something that once brought you great happiness and domestic contentment?

DS: This time I felt better equipped to face these emotions head on. I guess going through a period of analysis in the late Eighties gave me the tools with which to recognise certain idiosyncrasies that I needed to focus on. I was more adept at dealing with certain emotions as they surfaced. I began to recognise all the familiar traits and was able to work through them myself without the need for help. I am very involved in certain forms of meditation and ritual worship and so on, and I think having those practices gave me a relatively well balanced frame of mind, which helped me to look deeper into the darker aspects of my own emotional make up, and to emerge from it.

JC: You said that you were unable to write during the first period of profound emotional upheaval in the late Eighties, following the release of Secrets of the Beehive?

DS: Yes, music wasn’t a solace. I don’t think I would have worked at all if Robert [Fripp] hadn’t called and asked me to get involved with a project he was working on at that time. It was a very difficult time for both of us, for different reasons. In retrospect, I’m surprised that any work came out of that period at all. The work I produced then was quite raw, and I guess I was trying to find a voice for what I was going through. But I don’t think the context was quite right for me, and as much as I love Robert and admire him, I don’t think our collaboration was right.

JC: But the second time, when you entered a period of intense emotional turbulence, music provided an outlet and a release?

DS: This time, music was all that I had to fall back on. It could be of service to me in the way that it wasn’t back in the late Eighties. I’d just finished work on the retrospective for Virgin. I was ready for a complete break from all of that. And having built by own studio at home in New Hampshire, I was able to enter into a space that was entirely my own. I had the freedom to explore my own ideas and without the usual time constraints. I gave myself six weeks to work on Blemish but I could have gone on for as long as I wanted.

JC: You speak about the constraints of time: I presume you mean fiscal constraints, imposed by a record company?

DS: Money has always been an issue, yet somehow I’ve managed to survive without compromise. What was important for me was to find a voice for these particular emotions. There was this interesting contrast: as I’d end a day’s work, I’d be on a creative high, I’d feel that I’d really covered some new ground, but at the same time I was feeling utterly drained because I’d put myself through the grind of trying to give voice to these powerfully conflicting emotions. At the end of the recording, I felt a sense of pure catharsis. There was a real beautiful clarity to everything. I’d looked as deeply as I dared look at the side of myself that I’d prefer to keep hidden. It all sounds far more dramatic than it is, but the last few years have been very difficult to live through.”

JC: Can we talk more about the past – the past from which, it seems to me, you have long been in hiding. I’m talking about Japan, of course, and your years of pop celebrity.

DS: People say that I could have been as big as I wanted. But I was never interested in notions of fame or celebrity. It wasn’t in my nature. I didn’t have that drive, and I didn’t like the kind of personal attention I got, which might seem ironic when you consider the image [of David and the band]. But to me the image was part of the game of playing in that genre… I enjoyed that up to a point. But in the end nothing excited me about tomorrow with Japan. I thought we’d reached our peak.

JC: With Tin Drum?

DS: Yes. Making that album strained relations within the band considerably. We were beginning to close off from one another, which meant that we couldn’t give musically to one another. There were differing ambitions, and I was at odds with the band in my reluctance to perform live. They were also very dependent on me to write material. I was interested in material of a more Ghosts-like nature; we had such a strong rhythm section that they didn’t share that interest. Everything had to be of a more driving nature. Richard [Barbieri] and Steve were prepared to give it a go for another couple of years, but I’m not sure about Mick [Karn]. He’d already begun work on his first solo album while at the same time wanting to remain in the band as a kind of safety net. That was a luxury I didn’t think we could afford at the time.

JC: I was very curious when, in 1991, I heard that the band had reformed to make an album as Rain Tree Crow. But it didn’t seem to work out for you – and the old rancour, rivalries and disputes returned.

DS: Everything began well. We had so much fun working on the new material and hanging out again. But we took too long over it. We let it drift too long and we began to fall apart even before the album was completed. We had differences of opinion and money was a big problem, which put a lot of pressure on the band. Before then, we had been talking about doing a second and third album and live performances. Then the old tensions and frustrations re-emerged and you could see that there was no point in us taking it any further. In life, relationships run their course – that’s the case with me and Mick – and there’s no point trying to breathe new life into them. My brother and I didn’t speak for about five years after the end of the Rain Tree Crow project. This coincided with my moving to the States. Looking back, I’d say it was a healthy break.

JC: Will you return to live in London?

DS: It’s a possibility. I certainly feel more in tune with the cultural mood of Europe. When I first moved to the US, I lived in Minneapolis for five years. Those were years of domestic bliss such as I had never experienced before. We then moved to California, primarily to be near an Indian holy woman who was living up in the Napa hills. Then we were looking for a bigger property, where I could become more self-sufficient and build my own studio, which was why we moved to New Hampshire. The place we bought was a former ashram and it just had the most beautiful spirit to the land and property, even though the property itself was held together by little more than love, string and glue. Our house is on the side of the mountain, buried deep in the woods…

JC: It sounds remote.

DS: It’s not that remote. We’re only one hour and 15 minutes from Boston and four hours from New York.

JC: Are you frustrated with American politics, especially American foreign policy? Your song World Citizen was an old-fashioned protest song: a cry of anger.

DS: Well, there was so little dissent in the country during the build up to the war in Iraq, even in the New York Times. I was frightened by that. I wanted to write a song that would appeal to an American audience, [a song] that might even get some college radio play, and would have absolutely no ambivalence about it. It wasn’t really an artful exercise. But that whole period was enormously frustrating for me. Yet nowadays it is possible to create your own cultural environment, if you live as remotely as we do, what with the internet. You can avoid the worst excesses of America.

JC: Television, in particular, is awful here, isn’t it?

DS: Yes. Terrible. I don’t have one.

JC: How do you reflect much on your childhood in Beckenham, Kent? What did your father do?

DS: My father was a plasterer, a labourer. He was very meticulous in his work. He cared about what he did, but trying to provide for three children put enormous strain on him and he’s still paying for that today, physically and emotionally. I’m now very close to my parents. There was a time when I wasn’t very close to them but I don’t look back on my childhood as a happy period in my life. I meet people sometimes who speak of their childhood as the happiest period in their life. I can’t relate to that at all. I always had a desire to get away, to escape, and to try to nurture what I thought was missing from my home environment – aesthetics, a sense of beauty.

Later, over email, David returned to the subject of his childhood.

DS: Looking back there was a brutality to life in the suburbs of London. I’m sure it still exists. At home we were quite close as a family but not in an overtly intimate sense. Maybe it was a dependency based on fear, fear of what the outside world was able to inflict upon us. Steve and I inhabited a world of our own making as far as that was possible but allegiances could be swiftly switched and those in whom trust was placed could turn against you in an instance. We were always on our guard to some degree. The pressures on my father to support the family were immense or at least, at times, they must’ve felt that way to him. He fought hard to maintain the most basic of lifestyles. He’s a wonderfully goodhearted man but the strain of supporting us all occasionally showed in his relations with the family. Personal reinvention was a means of escaping from the environment that threatened to identify, classify, and therefore limit or suppress you. There was a tendency to allow oneself to be defined by others; by reinventing the self there was the possibility of escaping this definition and entering into the world of the imagination in which the possibilities for changing one’s life and environment were far greater. I suppose it was a case of bringing imagination to bear on reality: not just reinventing oneself but also potentially the world around you. Initially, the response was a protest against the absence of beauty. Later, it was an attempt to find beauty where there previously had appeared to be none. Despite my innate shyness I possess a strong will and an intuition, in which I implicitly place my trust, of how things should be approached artistically and achieved in a business generally indifferent to my output. Since the early-to-mid Eighties I’ve held the reins of my “career” (terribly inappropriate term for the trajectory my life and work have taken but I can think of no other) in my own hands, working in tandem with Richard Chadwick [of Opium Arts] as my confidant, business adviser, and facilitator, of the ultimately humble paths I’ve chosen to explore. As I mentioned to you when we met, I think the handicap of my shyness has spurred me on to attempt to communicate through the work in ways I was unable to communicate in life, to enter into conversation with the culture at large. Terribly important to my sense of well-being and my productivity.

JC: What about Japan: you never seem to speak well of the music you made then. But so much of it was good, for the era: the mood of records such as Gentlemen Take Polaroids and Tin Drum is very seductive.

DS: The trouble was I couldn’t write nakedly just as I couldn’t perform as myself on stage: I could only perform through some kind of image. Yet there are still some songs from that period that have a certain kernel of emotional truth…

JC: Like The Other Side of Life?

DS: Yes, that song, and Ghosts.

JC: Is it true that you considered giving up music while you were making Dead Bees to dedicate yourself to spiritual concerns?

DS: On asking Shree Maa whether I should abandon a life in music, a public life, I was told that music was my sadhana, my means by which growth is achieved. Both [my teacher] Ammachi and Shree Maa pushed me back out into the world to continue my engagement with it. It renewed my focus and gave me a different slant on being a pubic figure, however minor. I may have been guilty up until that point of separating the spiritual aims and those of my public life. I recognised that nothing falls outside of spiritual life and practice – nothing at all – and it’s this realisation that enables me to maintain perspective and balance in all that I do, and in all the roles that I find myself playing. At root comes the notion of surrender and from this everything else follows.

JC: I don’t quite understand what you mean by surrender.

DS: The notion of surrender is counter intuitive, at least for me. It is maintained from moment to moment by conscious awareness. This makes the practice a form of meditation. The commitment to those things undertaken is still 100 per cent; it’s only in the completion of the work, in one’s duties and responsibilities, that one relinquishes control, doesn’t invest heavily in a desired outcome. By performing ritual worship or puja at the start of each day, particularly while recording Blemish, I was able to maintain the perspective of witness, or observer, to my own predicament while simultaneously being immersed in the true emotional and psychological experiences that governed my life at that time. This allowed me the strength to go deeper into exploring these states without the fear of being utterly overwhelmed by them. I have to be honest and say that on some days it was a close call, but ultimately the practice saw to it that I was able to extricate myself successfully from the intensity of the experience.

JC: Did the life of a pop star never appeal to you – the celebrity, adulation, the money, the girls?

DS: I rarely partied hard. My sexual partners were few. During this period I remember spending much of my time alone whether at home, in various modes of transport, or in hotel rooms around the globe. Even in a crowd I was relatively isolated. Not an altogether undesirable state as far as I was concerned. I did have a problem with drugs during the period of the break-up of Japan, with cocaine. But that was more to do with my psychological problems than with any rock star excesses. I had a sleeping disorder whereby I couldn’t stay conscious for more than four hours at a time, and I was looking for some medication to help with that. This went on for months, and that’s when I became cocaine-dependent. In the end, I reached such a low with the drug that I knew I had to stop or face the consequences. For too long, when I was in Japan, I’d lived in a glass cage of my own devising, had grown up in public to a large extent and I simply wanted out, wanted the freedom to move, grow, unencumbered by fame and pop media interest. I had seen how necessary it was to invest almost equal amounts of energy in both the music and the personal profile to sustain the interest of the media. I couldn’t invest time in my celebrity: the notion had become anathema to me. I was fully aware that the avenue I was about to take musically couldn’t possibly compete with Japan’s success. I wanted to avoid the impression that this new direction had therefore failed me. I turned my back on the spotlight, such as it was, and moved to the more suitable dusk-like lumination of the spotlight’s periphery. The periphery is the area I inhabit in every aspect of my life. I used to resent this fact and fight against it often with disastrous results. I’ve now come to embrace the notion that this is my rightful place.

JC: How were the results disastrous?

DS: I guess that phrase sounds melodramatic but that’s the way I experienced these occasional forced deviations from what I now perceive as my natural place (periphery) towards the centre. You could usefully look at the entire trajectory of Japan’s career as being a result of such a deviation. It’s difficult to give personal examples of this. I can only elucidate a little by saying that when all the free-floating elements that constitute my life and work come to settle in place this is where I find myself and I’ve come to appreciate an intuitive “rightness” to this outcome. I might even apply this theory to my

current divorce and where that places me in the context of the family although I feel far from passive about this.

JC: I met your brother recently and he said something that I’ve been thinking about. What he said was this: “Throughout his adult life, Dave has shut himself off, with a partner, in quite an isolated situation…” I wondered what he meant by that?

DS: My brother is a bit of a conundrum himself, a dark horse, but a good man… dependable in life and work. It’s true that I don’t have a need for vast numbers of friends. I wouldn’t only apply the “shutting myself off from others” to my adult life either. This has been something of an ongoing theme since childhood but as Steve was my closest ally through much of that period he may not recognise the continuity into adulthood as such. In fact I’d venture to say that my isolation was greatest from childhood through to my early twenties until the break up of the band. My relationship with Yuka (Fujii), which commenced around the time of the break up, simultaneously narrowed my social circle but opened up my world in terms of cultural absorption, imagination, spirituality. The inner life. Yuka also brought me out of myself by introducing me to the mundane world, the simple day to day aspects of daily life. I suffered from a social phobia so profound that I was unable to enter a store or public transport without experiencing intense anxiety attacks. I didn’t have the vocabulary for it back then nor the professional help: I simply experienced the world as a fearful place. Yuka was the first person in my life to help me deal with these issues although she too had no background knowledge to help her understand my predicament.

In Portrait of an Invisible Man/the Invention of Solitude, Paul Auster says of his father: “…money in the sense of protection then, not pleasure. Having been without money as a child, and therefore vulnerable to the whims of the world, the idea of wealth became synonymous for him with the idea of escape: from harm, from suffering, from being a victim. He was not trying to buy happiness but simply an absence of unhappiness… Money not an elixir then, but as an antidote: the small vial of medicine you carry in your pocket when you go out into the jungle – just in case you are bitten by a poisonous snake.”

I read something of myself in this. It accounts, in part, for my ambition, against all the odds, as a young man. It was survival.

JC: I was thinking, because of what has happened between you and your wife, how you feel about finding yourself outside of a marriage and alone again. You gave the impression that as a young man you sought solitude, but is prolonged solitude something about which you are anxious, especially in mature adulthood?

DS: No, I can’t admit to being fearful of prolonged solitude but I do value friends and family. I cherish my solitude but also love to break that isolation frequently for brief periods. I guess that’s also what draws me to working with others – the spirit of community, camaraderie, shared objectives, the exchange of ideas, personal and collective challenges.

JC: What about ageing and death as you approach what… middle age?

DS: Late middle age now [he laughs]. They hold no anxiety for me. Death – it’s life that I’ve always found frightening.

JC: So you are not fearful of finding yourself alone?

DS: I have a greater fear of hurting others. People that get close to me have a tendency to get very close and I go through all kinds of torment attempting to step back a little from what I sometimes find to be the cloying or suffocating aspect of the relationship without causing hurt or rejection in the hearts of others. This hasn’t always been easy in my experience. Having said that I want to stress that I by no means take these relationships for granted. They are among the most treasured. That said, I’m uncertain if your question refers to a personal, loving relationship, or friendship in general. I adore sharing my life with a lover, companion, and sparring partner but I’m not afraid of finding myself without such a relationship although at times I yearn for it, miss it terribly. No, it doesn’t register as fear though. That’s not to say that one day that yearning couldn’t develop into fear of absence.

JC: Or perhaps your resilience and freedom-in-isolation arise from your faith-based awareness of the insubstantiality of the self and from a desire to be liberated from its primary emotions, if that is ever truly possible?

DS: There are challenges inherent in both solitude and relationship with others. It would feel cowardly to back away from either one for the sake of a more peaceful existence. Ultimately it should be possible to rest in either condition with equanimity. During this period of separation leading to divorce I’ve felt the need to call upon the friendship of others more frequently than at any other time in my life. I had powerfully conflicting emotions, the majority of which related to the incapacitating fear of hurting my children. So absolute solitude in these times has been welcome and beneficial. Partial isolation (still residing in the family home) has not.

JC: How are you feeling now? It seems as if this is a good time to have met you, both creatively and emotionally?

DS: I try to live on a fairly even keel. I don’t believe in being taken up too high or taken down too low, because at some point or another you’re going to swing back the other way. I genuinely believe that I’ve found direction for myself, in the short term at least, that I’m entering a period that is going to be enormously gratifying and challenging for me as a writer.

Jason Cowley is a senior editor on the Observer and a contributing editor of the New Statesman: Jason.cowley@observer.co.uk

Article on davidsylvian.com