An interview with David Sylvian and engineer Dave Kent about recording David Sylvian’s new records, Damage and Camphor. Recording and mixing techniques and equipment used during studio production.

by Chris J. Walker (Nov 1, 2002 )

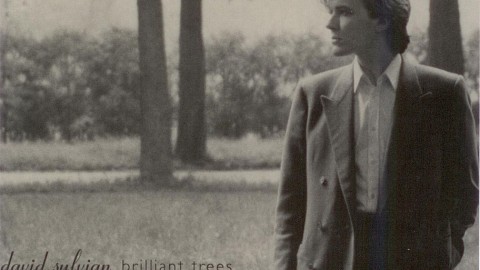

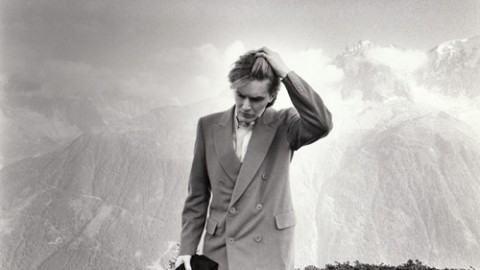

It might sound like lofty elitism to proclaim that British singer/songwriter David Sylvian’s music functions on a higher level than many other artists’. But there’s no disputing that his sonic sensibilities are far removed from what average rock/pop listeners gravitate toward. With his affinity for both western and Far Eastern styles, and his deft interweaving of themes relating to searching and discovery, existentialism and spiritual philosophies with progressive and ambient musical textures, he creates an intoxicating and heady brew. His reputation as an artful experimentalist has been further cemented by collaborations throughout his solo career with such idiosyncratic illuminati as Robert Fripp, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Bill Nelson, Jon Hassell, Holger Czukay, Bill Frisell and Kenny Wheeler. It’s no wonder that he’s become a cult figure for a certain segment of high-brow listeners.

Since his days as the frontman for the British glam-pop group, Japan circa mid- ’70s to early ’80s Sylvian has never been a chart-topping sensation. But he’s had a solid solo career, with many twists and turns, and has built a devoted international following along the way. And now, with his 21-year relationship with Virgin Records concluding, the singer/guitarist/keyboardist has released two separate collections of his past work Damage and Camphor which show some of the scope of his particular brand of musical genius.

The two sets provide contrasting views of this very private and enigmatic musician, who’s also a photographer, filmmaker and artist. Neither can be classified as best of CDs. Damage was initially released in Europe as a limited-edition album in 1994. It contains live performances from his 1993 tour with King Crimson’s frontman/guitarist Robert Fripp in 1993. But Sylvian says that he was never happy with the live recording’s mix, so he took advantage of the opportunity to fashion it more to his liking and re-release it. He also included the track Jean the Birdman as an alternate to Darshan, and repackaged the set with engaging new artwork from Shinro Ohtake. Camphor, on the other hand, is a two-CD set of Sylvian’s often ethereal instrumental work, with tracks dating back to his early solo releases, as well as including a couple of unreleased pieces.

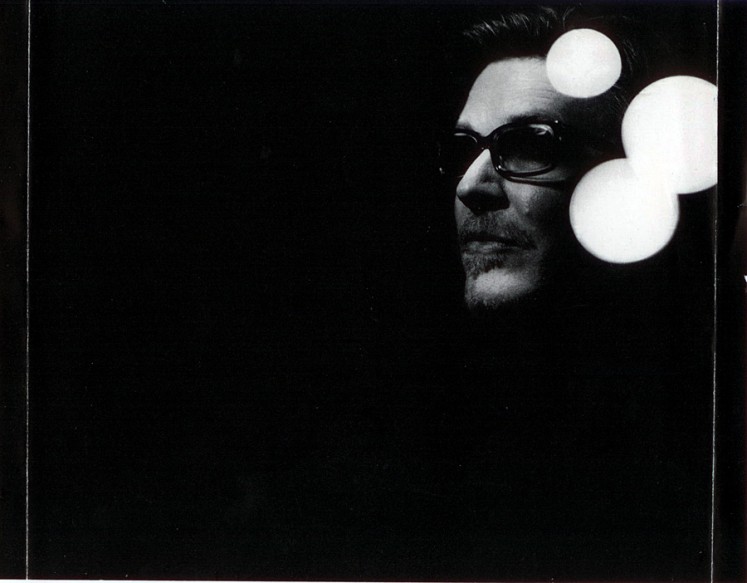

It’s all retrospective work for me, Sylvian says from his home in New Hampshire. Ever since I finished the Dead Bees album [1999], I’ve been working on past material. So it’s been a bit of a strange time for me, because I actually don’t spend that much time reviewing the work that I’ve done. Once I’m finished, I basically part ways with it and very rarely go back to check it out again. There’s been a lot of frustration involved with being just focused on this material, but at the same time, there were some positive aspects. Especially with the Everything & Nothing project [a two-CD anthology project released a couple of years ago], I was able to go back and complete things that would have otherwise wasted away in Virgin’s library. I enjoyed doing that aspect of the work, and also to have a second crack at certain pieces that I felt warranted a second or third attempt. But overall, I’d much rather be working on new material than going through things from the past. But it’s been necessary.

The original mixing of Damage was done by Fripp in 1994, with Sylvian absent from the process. Sylvian emphasizes that he thoroughly enjoyed touring and working with Fripp, and he even credits the guitarist with helping him overcome his reluctance to perform. But he says that their working methods sometimes conflicted in the studio, with Fripp constantly striving for a certain somewhat rigid level of perfection, and Sylvian preferring to remain flexible and weigh many options. Robert had the first crack [at Damage], Sylvian says, so this is my turn with the same material. Also, it’s mine and I didn’t feel the need to go back and consult him.

The actual work of reworking Camphor and Damage involved long periods of cleaning up and touching up the old masters using Pro Tools and stacks of outboard gear. Through the guidance of his engineer of 10 years, Dave Kent (whom he met while they were both living in Minneapolis; Kent was working for Prince at Paisley Park), Sylvian has become quite proficient with Pro Tools. Dave basically educated me in Pro Tools, Sylvian says. It’s totally intuitive for me, and I thoroughly enjoy working with it. That was a godsend and allowed me to work entirely alone when need be. Particularly when doing vocals, I enjoy working in isolation.

Because he had rarely listened to his past work through the years, Sylvian says that when he delved into the old selections for Camphor, he was surprised to find out how minimal they were in comparison to his newer material. Many of them used fewer than 24 tracks, in contrast to recent pieces that are twice that and more. Still, he says, The richness in textures and quality was all still there. I often go overboard and run over 64 tracks and not think anything of it. So it was interesting to go back to these 24-track analog tapes and realize that maybe we only used 15 or 20 of the original tracks and yet the pieces stood up well and sounded full-blooded.

Sylvian says that he was also caught off-guard by the power and spirit of many of the old tracks. It was the emotional impact of being drawn back into particular times and places, he notes. That was quite strange and intense, and I wasn’t prepared for that as I reconnected with the older material.

Engineer Kent says that he has come to greatly respect the artistic process that Sylvian puts himself through in the studio. He gets personally involved, the Wisconsin native says from his home studio in the Sonoma Valley region of California. (Sylvian previously lived there, too, and just recently relocated to the Northeast.) And he will be his own worst critic. When you take into consideration the caliber he’s trying to achieve, I think that works well for him. I don’t think another person would be able to communicate that to him as well as he can do that with himself. All in all, the level of musicianship and the people that he works with are astounding.

Back in ’93, when Sylvian and Fripp toured together, Kent mixed the shows. Unlike most studio engineers, he also does concert work, regularly going on the road with Sylvian. It’s exciting for me to know the music so intimately to begin with, Kent comments, and to then present it in such a fashion that it represents maybe not exactly what was on the record in a different environment every day. From more of an aesthetic standpoint, the most difficult thing is that David sings very quietly. So the loudest thing in the mix is basically the quietest thing on the stage.

Kent felt that unlike the concerts it was drawn from, Damage was dynamically lacking. Sylvian agreed, but just the same, it took the engineer close to two years to convince him to consider re-releasing it. We felt there were better tracks on the [ADAT] tapes and we could do a superior job, Kent recalls. And I feel like we did that with the re-editing and everything. It definitely was more involved than Camphor.

Because David’s catalog is so extensive, putting the material together for Camphor was kind of a chore. Essentially, we came up with his most personal compositions from a lot of different records. I felt that it’s important, because it re-introduces that material to a public that might not otherwise have been exposed to it. From a technical standpoint, it came down to picking out selections, remastering them and getting the whole thing down to 72 minutes.

Throughout his tenure with Sylvian, Kent has set up and operated studios for him in Minneapolis, Sonoma Valley and presently in New Hampshire. Like many engineers today, he likes to put his emphasis on matching the music with good-sounding preamps and other outboard gear, rather than obsessing on the recording medium. I try to use as much outboard gear as possible, he says. I use Earthworks and Summit mic preamps, and I just used the Millennia 8-channel unit. That’s the kind of front end I like to maintain, and then I use the Pro Tools to play and store the material. I’ll still always use my 480L, H3000 and a couple of PCM90s. I still like to try to keep the tube compressors in the chain as much as I can. But as far as density is concerned, we always try to get the sound we want to work with as close to what we want it to be ultimately.

With the revamped versions on Damage and Camphor, it was actually the opposite, with Sylvian and Kent stripping away elements, especially various reverbs and delays Sylvian felt sounded somewhat dated more appropriate to the ’80s (when they were recorded) than to today. My most recent work is devoid of effects of one kind or another, Sylvian stresses, so I tried to bring [some of the selections] into the present time in that respect. Also, he says, he wanted to find the core of those songs. In the case of Damage, he also re-performed a few vocal lines that he was dissatisfied with.

His retrospective period now behind him, Sylvian now has many enticing directions to consider, including touring solo, working with his brother (drummer Steve Jensen, who was in Japan and recently toured with him), soundtrack work, more one-off projects with other musicians or just getting back to his first love songwriting.

Whatever possibility he finally decides on, one goal is paramount: It has to excite me.

Original article on mixonline.com