“We shouldn’t ask that things be made too easy for us.”

A compilation of Q & A interviews undertaken in reference to the release and reception of Manafon.

Lets start with the word, Manafon. As soon I heard that this was the title, I thought, “Ooh, you’ve been to Wales.” Have you?

Well, I have but it was such a long time ago now that I can barely remember the circumstances.

It’s such a Welsh word. Tell us about the connection of your new work to this one word, which is a place in Powys.

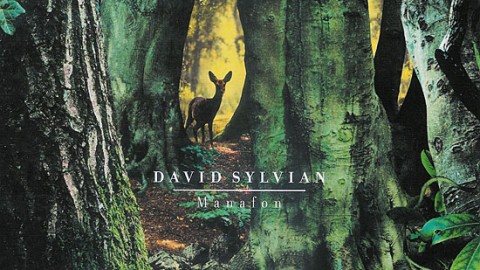

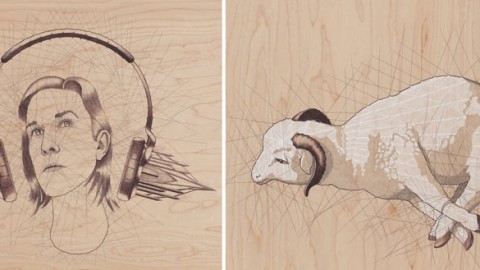

I came across the word in relation to the life and work of r. s thomas. It was the location of his first parish and the place where he wrote his first three volumes of poetry. Over time the word became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination, the creative mind or wellspring, hence the cover art of the cd depicting an implausible idyl if you will. A place where the intuitive mind taps into the stream of the unconscious.

Manafon, as RS Thomas fans will know, is the place where he was ordained as rector in 1942. Has he been an influence to you?

I don’t think Thomas’ life or work has had a direct influence on mine that I can detect.

How/when did you come across his work?

A dear friend introduced me to his work back in the 80’s. She’d loved the title of the volume of poetry she’d stumbled across and knew the fact that he was a man of faith would interest me, particularly as his poetry struggled with such issues.

Is it important to have met your influences?

Not at all. In fact it’s often better not to have come face to face with these figures in life. Writing about place is similar. It’s often better to have explored the place via the imagination before making the first visit.

In the song Manafon, you refer to Thomas as a “man down in the valley, who doesn’t speak in his own tongue”… a man who “bears a grudge against the English”. The song doesn’t paint him as an attractive individual, which I guess he wasn’t for some. What is it about him and his contradictions which inspire you?

I don’t feel the piece paints him in an unflattering light. It’s a bare bones character study which, if anything, presents a man for whom there’s no easy answers.

There have been books written about the man since his death that can better pinpoint the contradictions he embodied. It’s not a matter of what inspires me so much as what he represents for me. In some ways this austere, cantankerous old man is my grandfather, a man out of time. Rigid, damaged, wounded, immovable. On another level it’s the ideals that he tried to live by, the discipline and austerity he adhered to and imposed on others. His desire for self betterment, for answers to life’s big questions, but also the role he might personally play in the uplifting of his people, society. A noble outlook were he not such a terribly flawed individual (aren’t we all. no judgment there). His over identification with a nation to which he, in a sense, didn’t fully belong. So there was this quixotic element to his personality, it seems to me, a tragicomic element that wouldn’t look out of place in one of Beckett’s plays or novels. In fact he’d fit in beautifully. Then again, there’s the poetry which can be idealistic in its praise of the working man but can be profoundly beautiful and moving also. His own questioning of God’s silence, well, he railed against it at times as if faith had abandoned him. There’s such a rich complexity there and we’re only scratching the surface. These contradictions, this multifaceted character, although something of an anachronism in his own time, in some ways anticipates a contemporary predicament. On what does one ground one’s own life? In a world that’s rudderless when it comes to issues of morality, life values, where all is relative, where does one root oneself? It’s a philosophical question that we, at some point in our lives, and the earlier the better, have to begin to ask ourselves. While it might be liberating to be freed from dogma and, for example, the rules of the church, as a society we hand much of that power over to government which steps in as surrogate patriarch and plays the enforcer. This will lead, I’m certain, to outbreaks of violence against societal laws and strictures. If a nation doesn’t have a shared moral code how can it manage to order itself and maintain peaceful co-habitation without tighter and tighter reins being applied? With the death of god (as I recently read someplace, shot in the back of the head) on what energy field is the moral compass based? I feel that with the death of the notion of an external god, a necessary step in our evolution perhaps, to some extent we’ve also done away with the notion of ourselves as spiritual beings, as something more than flesh and blood. This imbalance will need correcting if we’re to continue to evolve holistically.

He was a man with a strong but complicated personal faith. Does that resonate with you?

It’s a matter of defining for oneself what gives one’s own life its shape and form, what are its defining characteristics, its sense of purpose? By and large, we’re all free to determine what these might be. With Thomas, the poet and the priest are inseparable but for me it’s the poetry which best gives his life its true definition. The freedom, ability, and the process to openly question aspects of his own faith, which I can only assume helped his personal growth in some manner (in Hinduism they might say this was his sadhana, his personal means for developing his spiritual awareness), must’ve acted as a considerable release for him. As a man of faith, as rector, his approach might have been too austere, out of touch, to the degree that it alienated people (by all accounts) but his poetry expresses his humanity which, at its best, rises above the specifics of faith and national identity to speak of the universality of the human condition. He dug deep into his own soul, as corroded and damaged as it might’ve been, and spoke with as true a voice as he could muster. This happens frequently in Beckett’s work. These heavily handicapped individuals are merely reflections of ourselves. In a sense Thomas might, on the one hand, represent some of the higher aspirations of the human spirit but, on the other, indicate how heavily handicapped each one of us is individually and what effort of will it takes to overcome that. Some of us bear heavier handicaps than others but as J.G. Bennett once said in a quote that is sampled on Robert Fripp’s album ‘exposure’ “if you know you have an unpleasant nature and dislike people, this is no obstacle for work”. Which I take to mean that, despite the most inhibiting of handicaps, work on oneself, in the spiritually disciplined sense, is always available to you. And again, same source; “it is impossible to achieve the aim without suffering”. The cause of this suffering is of course, generally speaking, ourselves.

RS Thomas isn’t an “easy” poet. He and his wife lived in the same house, but at opposite ends. They hardly ever spoke to each other, and only met at meal times. Yet after Elsi’s death, all these amazing poems started pouring out. Does love, or the notion of it and its difficulties, influence your own work? If so, how?

I would say the necessity and desire for love is an important underlying theme for me. This issue lies at the heart of a piece such as ’emily dickinson’. It’s a fact of life that not everyone experiences unconditional love, finds themselves or others un-loveable, aren’t willing to give, to sacrifice for the sake of love. Some simply cut themselves off from it. Withdraw. Yes, the theme of love or its absence is a constant preoccupation. To paraphrase the artist agnes martin, art is a celebration of the beauty in life or a protest against its absence.

How did you musically approach his new work? It certainly feels more easily experimental, picking up where Blemish left off.

I used the same approached that I developed when working on Blemish. This involved improvisational performances accompanied by a process of automatic writing. I expanded this approach by embracing the input of larger ensembles recorded live in studios in europe and japan. At the outset, I wasn’t sure if or how this was going to work in practice but after the first sessions, which were recorded in vienna in 04, and which resulted in a number of the pieces you’ll find on ‘manafon’, I knew I had unearthed an exchange which could yield fascinating results. That first session ran for seven and a half days. There was a lot of exploratory work done during that time. Many beautiful improvisations were captured but, as I was looking for something specific, something I wasn’t able to verbally communicate to the musicians involved, I had to gently nudge or cajole, make hints and suggestions, bring individuals into and out of the studio so as to change the internal chemistry of the ensemble, until I finally heard what it was I was looking for. This happened on the seventh day of the sessions, the last full day of work. The ensemble at that point in time was a quartet consisting of werner dafeldecker on double bass, michael moser on cello, christian fennesz on guitar and laptop and keith rowe on guitar. I’ve described this and the resulting work as a form of modern chamber music.

Once I knew the process worked I gave myself less time to produce results on subsequent sessions. The tokyo session in 06 was a one day affair, as was the london session of 07. I would work on the writing and recording of the lyric and vocal melody at a later point in time, sometimes as much as a year after the initial recordings were made. This gave the writing sessions back their spontaneity and freshness as it was like hearing the work for the first time (I’d made an initial selection of which tracks would work for me around the time the original recordings were made). I’d playback a given improvisation and start the writing process. After a matter of hours the lyric would be complete, composed simultaneously with the melody, which locked into precise queues heard within the improvisation. I would record the vocal on the spot meaning there was little time for revision. This is what I mean by a process of automatic writing. It was a matter of adhering to the process or the discipline and running with it until it felt complete. There’s a rapidity about the process which feels urgent, decisive and emotionally linked to the spirit of the original improv.

The music is kind of free-form, or at least that’s my impression. The melodies come from the voice. Is this a deliberate device?

Yes, the music is entirely free form. From my vantage point the melodies are suggested by what I hear in the improvisations. Whereas the musicians were playing with enormous restraint, I worked against genre if you will, and developed the lines that I heard suggested or alluded to. I used atonal sounds as punctuation, queues, a suggested key (sometimes all I had to go on was the hum of an amp or the buzz from the pickups on Keith’s guitar). Where necessary, I added my own musical contributions in the form of guitar and electronics. I also had a solo session recorded by the pianist John Tilbury which I layered into some of the earlier pieces.

What are the stand out tracks for you, or the most personally satisfying?

The greatest challenge was presented by what became ‘the greatest living englishman’ so that’s the centerpiece of the album for me. Melodically I’m fond of ‘snow white in appalachia’. I love Evan Parker’s solo on the coda of ’emily dickinson’. ‘The rabbit skinner’ is possibly the most autobiographical lyric on the album. It is an album that is conceived as a single entity though. A ‘song’ should stand up alone just as a poem, removed from the body of a book of poems, should do also. But to understand and benefit from the full resonance of the poem it’s best read in the context of that body of work. Of course, this is a decision each individual is free to make for themselves but it should be remembered that the album is a meta composition composed by the artist.

Do you consider the “listener” when you’re making your records? I mean, do you care about what they’ll take from your work, if they’ll like it? Or, to misquote Oscar Wilde, is any opinion better than having no opinion?

To create a work of any kind is an act of communication therefore the aim is to lend the material as much clarity as is possible without compromising it in anyway. You work in service of the composition. It makes demands and you do your best to adequately respond. Of course one cares what listeners take away from the experience but what you can’t do is anticipate a specific audience’s response to it or have one in mind whilst creating it. The strength of a piece comes from its internal logic, that it’s true to itself. That the piece might speak to a very small number of people isn’t its concern. The main consideration is that the essence of the work is uncompromised and communicated to the best of your abilities.

As to whether people like it or not, I’d prefer to think that with a work like manafon, they’re possibly having an audio experience unlike one they might’ve had before. There’s no intention to repeat an experience someone might’ve had, say, with Brilliant trees. We’re saddled with our past for better or worse but each individual release should rise or fall on its own merits. I’ve always had to deal with the fact that, whatever I produce, I will upset or alienate a proportion of my audience, occasionally to the point of losing them altogether. Some might complain the work is too ‘out there’ while others complain that the work isn’t experimental enough, that I’m merely repeating myself. Consequently, over the years I’ve lost some listeners and gained others. I guess I’m one of those infuriatingly ‘inconsistent’ artists who don’t tailor the work to any specific market therefore there will always be dissenters regardless of what I produce. Having said that I am incredibly grateful to those who’ve stuck with me, given me the benefit of the doubt, and taken pains to understand the reasons and the possible benefits for the, sometimes radical, changes in my output.

Leading on from that, some people would still like a less experimental Sylvian album, dare I say it, Secrets of the Beehive II. Can you see there ever being more work in this vein? More immediately accessible? Or is the process of exploring new creative avenues more important?

On hearing manafon for the first time, a friend and musician told me that, for him at least, it served the same purpose as Secrets of the beehive, was its contemporary reflection. I was grateful to hear that. It’s an observation I wouldn’t disagree with. I’d also point out that, at the time of ‘beehive’s’ release, the critics were not kind but openly dismissive or downright brutal. Consequently, it initially sold quite poorly. It’s easier to see things clearer in hindsight perhaps. Manafon doesn’t sound wildly experimental to my ears. Nor do I personally hear it as being a difficult album but I’ve always known the experience would be different for others. Time will soften its edges. It may sow the seeds for what might develop into a new genre for vocal music perhaps? Or maybe it’s simply a passing glitch on the digital face of popular music. I don’t know. But what I am sure of is that, over time, its abstractions will become much easier to embrace. After all, Debussy was considered impossibly avant-garde in his time. It’s hard to credit such a response to his music today. Similarly, Brahms piano concerto #1 was reviewed in its day as ‘noise’. We need to grow into modern works. We shouldn’t ask that things be made too easy for us. I’m obviously not comparing myself or manafon to these composers or their works, but it should be remembered that to be challenged is something of a gift if the work truly has something new to offer, a fresh perspective or experience.

Having said that, I haven’t abandoned form entirely. I may make a return to it at some point. For now, I’m leaving all possibilities open.

How important a role did your presence at the Erstlive event in Köln of 2004 play in your decision as to whom to work with on Manafon.

It had no direct impact in terms of the individuals I was interested in working with as these were decisions I’d come to, with the exception of the London session, some time in advance of attending the festival. Christian (Fennesz) invited me to attended the festival knowing full well my intentions believing that this physical introduction to some of the key players I was interested in working with would facilitate later negotiations when it came time to put the sessions together and in that respect attending the festival was very helpful (although, I hope it goes without saying, that it was an inspiring event to attend). Frankly, I was only in attendance on the first night of what I believe was a three day event but I met Keith, Otomo, Toshi, and sachiko at that time. Toshi confessed to being present at the Budokkan many years back when I performed with Japan. Otomo had heard Blemish and was openly complimentary about the work I’d done with Derek. For my part I’d was familiar with large portions of their output going back to Toshi’s work with Tetuzi at Off Site, Otomo’s large and varied output with all kinds of ensembles and collaborations, a personal favorite being the Filament series of recordings, and numerous other works, in particular, those recorded for/with Günter Müller’s label Four 4 ears and Zorn’s Tzadik, so there’s was an immediate rapport. Other listening during this period came from a variety of sources; Christian’s work with Polwechsel, ‘Wrapped Islands’ was another significant piece of the puzzle and of course the Matchless catalogue which doesn’t get the due attention it deserves containing as it does the Amm catalogue and numerous solo and collaborative efforts by that network of players, a truly fantastic resource. Jon Abbey’s Erstwhile label has released a prodigious amount of work over it’s relatively short lifespan which includes much of Keith Rowe’s best work outside of his involvement with AMM. It also acts as distributor for a number of other important and related works in the genre. Other labels of interest include Germany’s Grob, Hat Hut which has released much of Polwechsel’s work and has much to offer from it’s diverse catalogue of artists, Mike Harding’s Touch label which, again, houses a diverse range of recordings and artists, most notably much of Christian’s recent work, Mego.. the list goes on. There’s a fantastic wealth of material out there if you dig beneath the surface. So, I was aware of the backgrounds and histories of the musicians I was primarily interested in prior to the trip to Köln. As far as the musicians that constituted the London sessions; it was incorrectly reported in the Wire feature that I’d worked with the line up of Evan Parker’s electro-acoustic ensemble which would’ve been as pointless to my needs as it was financially restrictive should it have been strategically possible. As it happened I contacted Evan and sent him the work I’d done to date on the Vienna sessions so he knew what it was I was aiming for in the most general of senses. We talked about his work with the electro-acoustic ensemble, which was certainly a reference point, but also his work with the Evan Parker Octet as ‘crossing the river’ remains a personal favorite of mine and the scale of that recording had more in common with what I was aiming to achieve with Evan. The members of the electro-acoustic ensemble that were present at the session, aside from Evan himself, were Philipp Wachmann (who doesn’t appear on the final recordings) and Joel Ryan. The remainder of the ensemble consisted of John Tilbury, Christian Fennesz, and Marcio Mattos (Marcio was a wonderful addition to the ensemble and one I’m grateful to Evan for suggesting. It came about as a result of a series of exchanges between Evan and myself that helped narrow down just what it was I was after).

I didn’t go into this project blind or ill informed. In fact an important part of the entire process for me was deciding who was to be a part of any given ensemble, understanding that chemistry, as it allowed me to anticipate, within reason, the field in which we’d be working. That’s half the work done right there.

In a review in The Wire some years back for Sakamoto’s work with Alva Noto, Rob Young suggested, somewhat pejoratively, that both you and Sakamoto had sought out younger musicians working in the field of ‘electronics’ to revitalize your own works. In your case the reference was to your work with Fennesz. Do you feel that this was/is fair comment?

At root it’s an ill informed perspective that’s likely to be of complete irrelevance to the participating musicians or even the listening audience.

I couldn’t swear to it but I believe that in both the above mentioned cases it was the younger musicians who contacted Ryuichi and I. And by ‘younger’ we’re speaking of an age difference between Christian and I which is narrower than that between Ryuichi and myself so, really, how relevant a point can this be making? A collaboration should, ideally, be mutually beneficial otherwise there’d be no currency in the relationship. Mercifully, musicians do reach out to one another. There shouldn’t be stigma attached to the idea. When I first started putting calls into musicians back in the early 80’s I was told by some of these amazing players that they rarely, if ever, received requests, out of the blue, from musicians they’d previously not met or had some sort of family tree connection with. They were grateful, as was I, that our somewhat hermetically sealed worlds were broken into, that the scope of the horizon was stretched a little wider. With the collapse of the music industry and the intervention of the internet, that global networking is now second nature to most musicians. It wasn’t always the case.

I’m sure you anticipated quite a mixed bag of responses to Manafon. Outside of the critics who found themselves simply unable to place it or even pass judgment upon it did a couple of the openly hostile ones impact you in some way? How do you digest this kind of ‘criticism’.

To be honest, I sidestep the matter of digesting altogether by avoiding them. The last thing you need is a second critic in your head as you tentatively take first steps towards something new because your own critical faculties are more than up to the task. Being overly aware of the viewpoints of others would simply encourage the critical factor to go into overdrive which would completely undermine the intuitive process altogether. The opinions of others, whose motivations are open to question, don’t come into it. Once a work is well underway you might seek the viewpoints of people whose judgment you value. And by that I don’t mean that the response will be positive or encouraging, sometimes the opposite can be equally valuable. If a certain someone heard the work and passed comment of a negative nature, aware of the history of such comments from this individual you’d know whether the work was on course or not. In other words, you don’t take these things at face value but in the context of the history of the individual’s interests and limitations perhaps. But general opinions that give an overview of the almost completed work are only so helpful anyway, By that time you’ve already followed your instincts a long way down a very difficult path with plenty of time for self doubt, criticism etc., to have been digested, worked through on some level or another. What’s more important in the process of making a work is not confirmation of a general kind. It works along the lines of dealing with specifics. Does that bass have enough low-end to it? Will I get away with that much background noise from the room? Can you hear the edit on the piano at 2:32 mins? Very mundane stuff, but that’s how exchanges with trusted loved ones tend to be focused.

I did feel a certain trepidation once Manafon was completed, not because I felt I’d fallen short of my own goals, but I wondered would they make sense to anyone else but me? I personally know so few people with a musical background with significant breadth to understand what it is I’d attempted to achieve. But there were a few lone voices, belonging to people whose opinion I value enormously, that gave me reason to believe the material was accessible, that its subject matter wasn’t either overwhelming or too tightly guarded, and that this unlikely collision of genres and aesthetics made sense to more than just myself. In short, that it worked. Really, that’s all one needs to know.

It seems that in terms of the public that might be attracted to a work of this kind you’re going to come up against obstacles from both sides of the fence. This must’ve been obviously to you from the start, no?

When you say ‘both sides of the fence’ I imagine you’re talking about my presumed audience and the audience that my collaborators enjoy? Yes, of course, the work potentially alienates both. It takes an open mind to get close to the material. If you come with certain expectations firmly in place you’re not going to find access all that easy. There’s nothing I can do about this supposed division of interests, nor would I have attempted to address it if were a possibility to do so. The work wasn’t trying to satisfy a particular niche audience (niche markets are fiercely guarded by everyone with a stake in them with the exception of the majority of the artists themselves). As mentioned before, it was a work born out of personal needs. I’ve spoken about the genesis of the work quite extensively but I feel no need to defend the material. It’ll have a life of it’s own. It’ll work its way out into the world at its own pace. It’s in no hurry.

And finally, can you say something about the samadhisound label and its future?

samadhisound came into being almost of its own volition. Running a label wasn’t something I anticipated as being on the cards for myself but I’ve enjoyed my involvement in samadhisound quite considerably. There have been periods where I’ve fought for its survival because we’d come a fair way in establishing it on a fundamental basis and it felt premature to let the enterprise go. Having said that, we can see that the business and media are changing rapidly and that sales are in decline. If it wasn’t for the hard work of a few good people the label couldn’t possibly have continued to exist as a platform for as long as it has. With that firmly in mind I only look to the year ahead. I believe 2010 will see more releases on the label than in any year prior. Rather than indicating the health of the industry or label this simply reflects the number of projects that have reached my ears that I’ve wanted samadhisound to be a part of. As frequently said in reference to my aspirations for the label; it’s possible to plant an apple tree without harboring dreams of an orchard.