By Brian Nixon

Special to ASSIST News Service

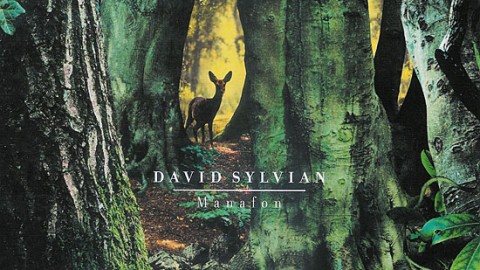

Hands down, my favorite musical release of 2009 was British musician David Sylvians masterpiece, Manafon. It is an album of stark beauty and personal confession. Even the word brilliant is too shallow to describe it.

My initial attraction to Manafon was the teasing interplay between Sylvians music and the title of the album, usually associated with Christian clergyman and poet R.S Thomas.

Manafon is small village in the county of Powys, Wales, UK, where Thomas lived and wrote much of his finest poetry.

By using the name Manafon, was Sylvian dropping us a hint? Was Sylvian seeking a new haven for his music and life? The artwork on Manafon seems to say so: green forests, deer, foxes, and rabbits abound. Life is manifest.

But then mystery enters: The artwork also shows Sylvian holding a dead rabbit.

In many cultures around the world, the rabbit symbolizes life, philosophy, and values. Was the artwork used on Manafon communicating that Sylvian is seeking a new lifedying to his previous philosophy? Was the dead rabbit in Davids hand representative of a changing value system?

Can´t be too sure.

But what can be said is that Sylvian values art, and most of the artwork he has used throughout his 33-year career is well thought out and of high quality. To me, there seems to be rhyme and reason behind the use of the symbols.

Another intriguing question entered my mind based upon the lyrics of several of the songs on Manafon : Was Sylvian leaving his eastern mysticism (a combination of Buddhism and Hinduism) and turning to a monotheistic worldview?

Though not clearly stated in the lyrics, whispers of lyrical discontentment seem to indicate this may be the case.

Sylvian sings in the song Small Metal Gods:

I´ve placed the gods

In a Ziploc bag

I´ve put them in a drawer

They´ve refused my prayers for the umpteenth time

So I´m evening up the score

If this song is personal in nature, its quite revealing. Sylvian sings that he is putting away the gods and is evening the score, possibly turning to the antithesis of a polytheistic worldview: monotheism. In other words, Sylvian may be turning to the God who does answer prayers.

On a personal level, I have felt Sylvians best work always connected to a monotheistic, Christ-centered worldview. As far back as 1983, Sylvian has had an ongoing discussion with Jesus Christ.

In the song Forbidden Colors, co-written by Ryuichi Sakamoto for the movie Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, Sylvian writes:

The wounds on your hands never seem to heal, I though all I

needed was to believe. Here am I a lifetime away from you. The blood of

Christ, or the beat of my heart.

Theres no question about the topic of Forbidden ColorsSylvian wrestled with the person of Jesus of Nazareth.

Sylvians breakthrough solo record, Brilliant Trees, also had conversations with a Judeo-Christian worldview. On songs such as Weathered Wall, he wrote:

You were someone to believe in

A place for hope in a changing world

Feeling every moment

Every one of the years spent in your arms

After a lifetime of living

These soiled hands show no life at all

Working at all hours

Never facing the fears here in my heart

Grieving for the loss of heaven

Weeping for the loss of heaven

By the wailing wall

Then again in 1986, Sylvians whole album, Gone to Earth, is replete with Christian symbolism and themes (albeit mystical).

From 1987 to 2003 (the year Sylvain released Blemish, an album questioning much in his life), he turned his attention toward Eastern mysticism.

In an article written for Spike Magazine entitled David Sylvians Religion: An Interview and Interpretation, Darren Middleton wrote that Sylvian focused on the Upanishads, or Vedanta (end of the Vedas) the basic feature of Vedanta is the notion that spiritual truth is not found through a process of individual inquiry, as with Soto Zen Buddhism, but by filial devotion and surrender to a spiritual master or guru.

The bottom line is this: though the past two decades of Sylvians career was influenced by his interest in Eastern mysticism and religion

(on albums such as Dead Bees on a Cake, Approaching Silence, and Darshan), the fact is that Sylvian is no stranger to a Judeo-Christian worldview especially in his early career.

On some level, Sylvians artistic output can be represented as a dance between his interest in polytheism (as represented by Hinduism) and monotheism (as represented by Christianity).

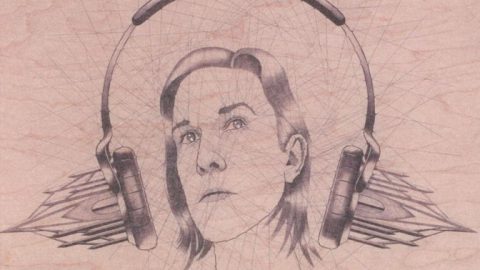

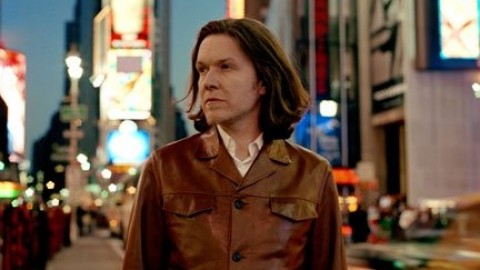

So imagine my surprise as I opened up the new album by Sylvian entitled, Died in the Wool: Manafon Variations, only to see the artwork by Irishman George Bolster, reaming with Christian symbolism (http://www.georgebolster.net).

My speculation deepened.

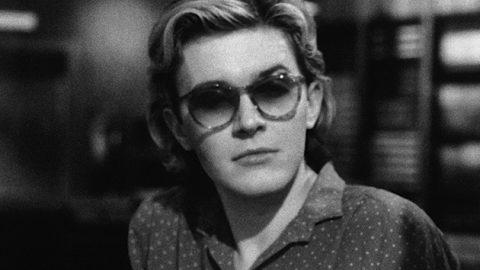

On the cover of Died in the Wool is a portrait of Sylvian with headphones not touching his ears. Protruding out of the headphones are what appears to be razor-like flames or some type of ice formations. The name of the portrait is Manaphone; an obvious tie-in to his album Manafon, upon which much of the new music is taken.

On the back of the CD is a portrait of a lamb with its legs tied together, reminiscent of several masterworks depicting Christian symbolism. The name of the work is To Bind a God.

On the inside of the CD is a side portrait of Jesus in a loincloth, hands tied by an elusive wrap and handcuffs. The portrait appears to be a depiction of Christ before His crucifixion. The work, as stated in the liner notes, is Christ: The Original Hippie.

As you open the CD, a credit sheet is given. On the front of the sheet of paper, the hands of Christ are highlighted. No longer elusive as depicted in the middle of the CD, the hand binding is clearly seen. Written on the hands is the word love.

The symbolism between the three pieces of art in the CD is quite clear (at least interpreted by its surface meaning): The bound lamb is Christand Christ is love. Even the title of the album Died in the Wool points to a larger symbolic concept: the wool symbolically represents the

Lamb, which is Jesus. And as the images portrayed in the CD case reveal, Jesus is ready to die.

The only intriguing element within the totality of the art is the front cover: Sylvian is not listening to the earphoneshes looking up in contemplation.

Is Sylvian thinking through the dilemma he posed on the album Manafon? Is he no longer listening to his former path of Eastern mysticismas portrayed by the razor-like ice or fire? Is he burying the small metal gods looking for the God of love? Or, is his possible return to

monotheism a variation (as the subtitle of the Died in the Wool states) of his overall spiritual quest?

Again, we may never know.

But many of the compositions on Died in the Wool are variations on works first presented on Manafon. In a way, the music is an expansion on his previous masterpiece.

Helping Sylvian develop these musical themes are some fine musicians and composers, including Dai Fujikura, Christian Fennesz, and Werner Dafeldecker. They are artists of the highest caliber, creating audible paintings from their performance and arrangements.

The take home point in all if this chatter is simple: Sylvian created another intriguing artistic album, a masterwork all its own.

Though dependent on Manafon, Died in the Wool is a stand-alone album worthy of repeated listening and analysis. It is truly high art.

And concerning the Christian symbolism found throughout Died in the Wool, if Jesus inspired such wonderful art within the life of Sylvian (and

Im not saying that He has), then thanks be to God. If Jesus inspires people to create art such as this, then I say give us more of Jesus.

Like countless artists throughout the centuries, the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Christ has elicited and produced some of the greatest works of art in history. And if Sylvian continues with this inspiration, his works may one day sit on the mantle with those who have treaded the path before him: creating beauty for Gods glory.

For a wonderful review of the music on Died in the Wool. I recommend All About Jazzs, John Kelman, astute assessment of its importance. (http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=39607).

Brian Nixon is a writer, musician, minister, and family man.