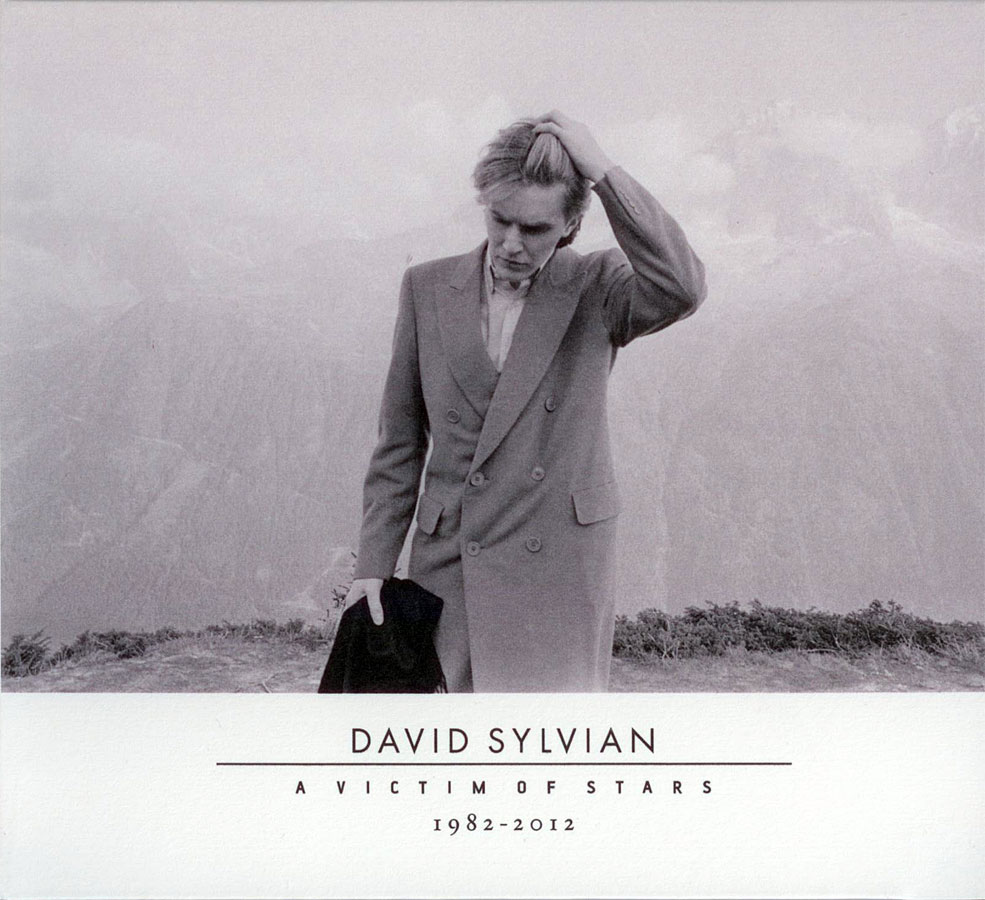

as published on The Quietus, by Wyndham Wallace, March 19th, 2012 08:25

A new compilation, A Victim Of Stars 1982-2012, celebrates thirty years of solo work by David Sylvian, who guides Wyndham Wallace through some of its highlights.

Remarkably, it’s three decades since David Sylvian released his first solo single, the twin pack ‘Bamboo Houses’ / ‘Bamboo Music’, a collaboration with Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Ryuichi Sakamoto. The former frontman for Japan the band he formed with his brother Steve Jansen alongside the late Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri and Rob Dean in 1974 has since released eight official solo albums, as well as a number of collaborative records with the likes of Robert Fripp, Holger Czukay and Burnt Friedman, and is currently lining up his next three releases (of which more next week). In advance of an in-depth interview with the cultivated and creatively restless owner of one of music’s most romantic baritones, he guides us through ten of his back catalogue’s finest moments

‘Forbidden Colours’

(1983)

“I guess after the band had broken up, I wasn’t sure what direction I was going to move in. I didn’t write anything for a period of time, which was unusual for me. And then Ryuichi gave me ‘Forbidden Colours’ to work on and it opened the doors for me a little bit. Suddenly the flow of writing began to really just open up and new material began arriving.

I thought it was beautiful. I mean, sonically it was incredible. I loved all the samples that he was using. And we were so very much into sound design at the time, between Yellow Magic Orchestra and what we were doing at that point in our evolution. So sound design was a big part of it for us, and what Ryuichi as producer did was extraordinary with that particular piece of music. And the melody itself was outstanding. Originally I don’t know if he told me afterwards or before my writing the lyrics for the track Ryuichi expected me to write a melody along with his written melody, to sing the melody that he had written. But I had found that that was impossible and undesirable. So it was counter to the melody. I tried to find something that would work with it but it was a counter-melody that sat comfortably with the original melody that he had created.

I would watch Ryuichi in the studio with Bertolucci over his shoulder telling him, ‘A little more of this, little less of that’, and what have you, and Ryuichi’s very malleable in that respect, and very open and flexible. And I think that’s a virtue, but it’s not one that I have.”

Brilliant Trees

(1984)

“I decided to pull together a group of musicians for the recording of Brilliant Trees. I didn’t want to work with session artists because I wasn’t used to that. Bands are generally very passionate about the work that they produce and, on the few occasions I’ve worked with session musicians, the passion wasn’t there. You didn’t feel a real connection between their contribution and the work itself. And that’s understandable. So I wanted to work with a series of artists that I respected and I would tailor the arrangements of the songs around their involvement.

So I had specific roles for everybody that I invited to work with me on that album, but I wanted one wild card, something unpredictable, and Holger Czukay was that person for me. I really adored what he had done with his first solo album, Movies. I still think that it’s a work of genius. I think that’s an utterly stunning record. I just said, ‘Come along and we’ll see what happens’, and we got on famously and he became a very close friend of mine, and what he contributed to the album was kind of what I was looking for, which was mainly supplied by the IBM Dictaphone that he used to play back samples. Samplers in those days were completely inflexible. But he’d found this IBM machine two of them in a dumpster outside an office building in Cologne, and he could move the playback head of the Dictaphone across the tape at random speeds, and so it really made it a marvellously flexible instrument.

Gone To Earth

(1986)

“That album was put together piecemeal. I started on a variety of different musical projects but I hadn’t one specific direction. I had the soundtrack to the film Steel Cathedrals, I had Words With The Shamen on the go, and added to that was a body of work that didn’t necessarily sit well together. I then started writing songs, and I started recording a number: ‘Wave’, ‘Before The Bullfight’, ‘Laughter And Forgetting’. So I ended up with this kind of what do you call it an incohesive collection of material, that I somehow had to make sense of. So what I did was persuade Virgin to put out the Words With The Shamen EP, put Steel Cathedrals to one side for the time being I think it was released as a video only at the time and then take the songs that I’d been working on and sort of develop them further and flesh that out into a full album.

But I’d also been writing these little instrumental pieces which I really loved, and I wanted to pursue them as well. And the deal was that the budget for the album would not cater for the instrumental work, and if I wanted to produce it then I had to produce it in the off hours, like the end of a session or the very first thing in the morning before sessions got underway, and therefore produce it in my own time and at my own costs. So that’s what I did. But for me it was a body of work, the instrumentals and the songs belonged together, and Virgin did allow me to release the album as a double ultimately. I’m not sure that they were that enthusiastic about it at the time, but they didn’t put up too much of a fight on the creative issues.

Secrets Of The Beehive

(1987)

“That’s an odd record, really, because just prior to that I’d been on a really extensive press tour for Gone to Earth which was just taking me all over the globe, and I was quite exhausted talking about the work and didn’t feel quite ready to sit down and embrace writing at that moment in time. But it just started coming to me, as soon as I had settled back into my home the material started arriving, and in a period of about two weeks everything was written. And it wasn’t something that I’d planned on doing: I hadn’t conceived the album in its entirety, as an entity in itself, it’s just a batch of songs that sort of arrived and fell in my lap. It felt like a gift. I recognised that there was a beauty to the material and it already felt to me like something I had heard before. It felt like it was going to be around for a while, and I don’t know why it felt that way, but every time I returned to one of the pieces it felt so familiar, like this has been around a very long time, it’s going to be around for a long time to come. So it was very much a gift to me in that respect.

Secrets Of The Beehive was met with a considerable amount of hostility in the press, and on top of that there were pieces missing that I never got to complete. I just ran out of budget and there wasn’t any more forthcoming to allow me to complete the record as I envisioned it. So, although I liked the material on the album, the centrepiece is missing, so for me it was something of a failure.

Plight & Premonition

(With Holger Czukay, 1988)

“We didn’t plan to make an album together. Holger Czukay actually invited me to Cologne to put a vocal on a track for an album that he was recording. And the first night that I arrived it was late in the evening. He suggested we have dinner, and we came back to the studio and I just sat down and started playing. And I just walked around the room from instrument to instrument and I wasn’t always aware of what he was recording, and that’s really the way that he likes it.

As soon as the performance became too self-conscious, he’d wait for me to start up with something else. It was created over a period of, I think, two nights, possibly three. I never got to record the vocal for him because it was time for me to leave at the end of that period, but we’d come up with something far more interesting, I think, in the process.”

The First Day

(1993)

“That was at Robert [Fripp]’s instigation. It was at a time when I think I would have fallen silent anyway. I had no desire to work at that period in time, and Robert was really tugging at my sleeve saying, ‘Let’s do something, let’s do something,’ so why not? And so that was an interesting journey in itself, and we worked together for a number of years before calling it quits. And then I was able to return to solo work”

Dead Bees On A Cake

(1999)

“I just came up with so many problems with producing it. So many avenues just ended in a kind of a dead end. Using a great deal of new technology this time, a lot of files were lost along the way, but that wasn’t the only problem. Certainly working with different musicians, a couple of producers, I just put a halt to the project numerous times. And at the same time I’d moved to the United States, I’d got married, I had my first child and I was very much involved in that life. I was just so involved in the bringing up of my first daughter and following a far more intensely spiritual path and a spiritual discipline, and that was kind of leading me away from a concentrated focus on music. And every time I returned to the work I liked what I heard, but again every time I got re-immersed in it I would come up against an obstacle of some kind. I just thought it did not want to be completed and thought that maybe this was it.

I was happy with the work. It was poorly received, but it did bring my relationship with Virgin Records to an end. I didn’t realise how much that would mean to me, but it really did liberate me, and I only recognised that fact once I was in the studio recording Blemish and realising that I really didn’t have to go round to sell this idea to anyone. It really opened things up for me, moving away from a major label like that.

Blemish

(2003)

“It was very cathartic. It’s an odd one to talk about, because obviously I was going through a break up of a marriage and that was very painful, but as I got into the studio and shut the door I would allow myself into the darkest recesses of my heart and my mind to uncover what was there. And I would feel that to be quite dangerous in life it’s not something I would encourage but in the creative process it seems incredibly liberating to be able to access these more negative darker emotions and acknowledge them. So I worked on the album daily for I think it was six weeks, and each day I was more or less writing a track, and I’d flesh it out over time, and at the end of each day I’d listen back to what I’d done and feel elated by what I heard, which was an odd way to relate to the content of the material because of its nature in essence. But I felt like, Gosh, this doesn’t sound like anything I’ve ever done before, or anything I’d heard before, so it felt very exciting.

So once I’d left that wonderful cocoon in which one could explore these emotions, I entered back into the real world of those emotions, and it was still an extremely difficult time, but as I think it was Robert Lowell said, ugly emotions produce beautiful poetry sometimes, and that’s definitely true of Blemish.

Snowborne Sorrow / Money For all

(Released under the name Nine Horses, 2005)

“It was actually started prior to Blemish. I was building a studio at the time and, upon completion, my brother (Steve Jansen) and I sat in the studio for a couple of weeks and started writing material together. And I was really happy with the material that we were writing together, but we were writing incredibly slowly. Put my brother and I in a room together and we can be very fastidious and really it can take a long time to produce a body of work, and I needed to do something more immediate because I hadn’t created new work in such a long period of time. And I felt this burgeoning sense of something needing to be expressed and, you know, it was what was to become Blemish. So I just asked Steve if we could put this project on hold for a six week period and we’d get back to it.

On the Blemish tour I met up with Burnt Friedmann, and we expressed a desire to work together, so I started working on material with him for a supposedly different project. I finished that project and handed the material to Burnt. Burnt mixed it, and I felt that the material hadn’t achieved its full potential, and I asked if he could send me the files so that I could have a bash at the material, and he was generous enough to do that. It kind of began to merge with the material that I was working on with Steve, and I added Steve to a lot of the tracks that Burnt and I had written together, and I think Burnt contributed something to the material that Steve and I had worked on together. So I basically became an overseer of these two separate projects and tried to bring them together as cohesively as I could. And they made sense. They made sense together. They complemented one another nicely.

And I was really proud of that record. I thought it was again not something that had been planned with a lot of forethought, but over time I became I began to envision it as a whole and managed to pull it together in a way that really made good sense to me. It was a return to the kind of songwriting that I’d been involved with for years. Now I find that I’m able to go back and forth quite easily between more traditional songwriting forms and more improvisational forms. They’re just different strands of the work that I intend to continue producing. I don’t see that they’re at odds with one another. I enjoy the contrast, to be honest

I loved working with Stina (Nordenstam). She’s super talented. She’s got this instrument that she knows perfectly well how to get the best out of.”

Manafon

(2009)

“I know that Blemish is probably my most celebrated work in terms of the critics’ response to it. That’s just from what I’ve heard. And that’s wonderful. It’s an album I’m very proud of. And you could say maybe an album like Manafon has received a lot of negative press, which is what I’ve heard. But it’s a still a path I intend to pursue musically, working with improvisation in some form or another. So you just follow whatever you feel is right for you. You follow your instinct and that’s all you can remain true to.”

Original article on The Quietus