Nenad Georgievski is a well respected music reviewer known for his work on All About Jazz.

This interview is for me the definite Manafon interview. No need for more same question and answer interviews anymore. This interview has been re-pubished with kind permission of the author.

Many artists deliberately avoid taking risks, making changes instead opting for the safe, but David Sylvian is not one of them. Across his illustrious career, Sylvian has always sought to take listeners out of their comfort zone. Self-consciousness and introspection permeate every corner of his works. His most riveting songs have explored various topics, including spirituality and soul-searching for the modern world. His songs are evocative and fragile, confronting the listener about the challenges inherent in being human.

In the 1980s David Sylvian rocketed to stardom in space-age garb with his band Japan, which he disbanded at the height of their popularity in 1984. The end of that band actually began the reinvention of an artist who sought to pursue a challenge and more personal vision. Since his debut release, Brilliant Trees, Sylvian has crafted a remarkable career, blending his deep and resonating voice with studio sorcery.

The albums that followed, such as Gone To Earth, Secrets of the Beehive, Plight and Premonition, Flux + Mutability, Rain Tree Crow (the brief reforming of his former band, Japan), The First Day, and Dead Bees on a Cake were nothing short of brilliant.

Simply put, Sylvian finds infinite joy in diversity. His output as a leader and collaborator criss-crosses multiple musical universes, including jazz, pop, soul, world, progressive, electronica, and the avant-garde. The production values and supporting players on his albums are of the highest order: Holger Czukay, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Jon Hassell, Evan Parker (seen below with Sylvian), Bill Frisell, Marc Ribot, Bill Nelson, Robert Fripp, Mark Isham, Michael Brook, Arve Henriksen and Derek Bailey.

Sylvian’s albums occupy a unique place in the relationship between the visual and aural arts. Himself a painter, he knows the impact of artwork on the perception of music. The artworks on his recordings are truly magnificent, with contributions made by Russell Mills, Ian Walton, Anton Corbijn, Yuki Fuji, Charles Lindsay, Shinya Fujiwara, Atsushi Fukui and Ruud van Empel.

For most of his career Sylvian was a Virgin recording artist, until 2000 when he ended the relationship by releasing two brilliant compilations: Everything and Nothing, a vocal compilation, and Camphor, an instrumental one. Both uniquely summed up his career, giving a fine portrait of an artist.

In 2003 Sylvian founded the Samadhisound label, a place where music and art coexist peacefully. Besides his solo works, the label brings various artists to the fore, such as Harold Budd, David Toop, Akira Rabelais, Steve Jansen (Sylvian’s brother), Sweet Billy Pilgrim, Thomas Feiner & Anywhen. The first release by this label was Sylvian’s all-improvised album Blemish. It was soon followed by a remix album, Good Son vs. Only Daughter, Snow Borne Sorrow by Nine Horses (a collaboration between Sylvian, Steve Jansen and Burnt Friedman), Money for All and Manafon.

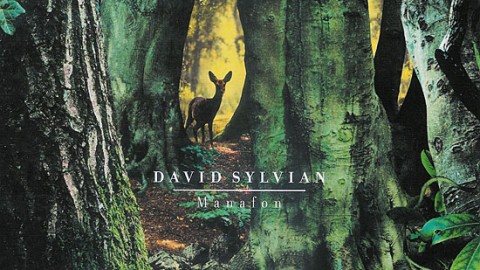

Astoundingly, after scattering eighteen studio albums over a span of nearly thirty years, David Sylvian is showing absolutely no signs of slowing down. If Sylvian, whose recording career in music stretches back to 1978, had followed in the footsteps of so many of his own contemporaries, we might have written him off more than two decades ago. Sylvian’s most recent studio album, Manafon, is without question one of his most challenging ones Manafon is a recording of an all-improvised nature, where a stellar cast of improv musicians were cast. The end result was a recording with strange, unusual textures where the music and the voice collide and intertwine beautifully though they come from two different worlds.

Astoundingly, after scattering eighteen studio albums over a span of nearly thirty years, David Sylvian is showing absolutely no signs of slowing down. If Sylvian, whose recording career in music stretches back to 1978, had followed in the footsteps of so many of his own contemporaries, we might have written him off more than two decades ago. Sylvian’s most recent studio album, Manafon, is without question one of his most challenging ones Manafon is a recording of an all-improvised nature, where a stellar cast of improv musicians were cast. The end result was a recording with strange, unusual textures where the music and the voice collide and intertwine beautifully though they come from two different worlds.

Thirty years into his recording career, David Sylvian is still making music that he wants to make. And, like all great artists, he’s making music that only he can make.

All About Jazz: Many years ago you gave up fame and stardom and survived. Although you don’t lead the life of a pop star and you keep your private life private, you still sell records in huge quantities. The concerts are usually sold-out. Can you describe your relationship with your audience? You still have quite a few hardcore, loyal fans out there.

David Sylvian: I can only deduct certain truths regarding the audience for my work, in the same way that anyone else closely observing the situation might. There are a number of travelers who have undertaken the long journey from pop stardom to the present with me. You could say we’ve been maturing together. You might also be willing to admit that, in their listening habits if in nothing else, they enjoy a good challenge. There are other listeners that tend to jump on and off the wagon when it suits them, possibly tuning in for the vocal work and out for the instrumental (or, in some rare instances, vice versa). (There are) still others whose curiosity is piqued by a particular recording. I come face to face with the audience (I won’t be presumptuous and call them ‘mine’) in the arena of the concert venue. In this respect I’ve almost universally found them to be the most generous, respectful, gracious audience an artist has any reasonable right to expect. More than this I cannot say.

AAJ: The music you create has a long-lasting beauty, and in a way it reflects a lot about you. What would you like people to take away from your music? What sort of response or feeling do you hope is evoked in your listeners?

DS: I have often said that the desire is to blow the listeners’ hearts wide open. By this, I mean I want them to be moved to the point of abandonment. This would be beautiful, an ideal, but it is too much to expect. That the work might resonate in the lives of others is no lesser achievement, and one I might more modestly aspire to.

AAJ: The artwork on your album covers has been like an art gallery exhibition with works by Russell Mills, Anton Corbijn and Yuka Fuji. Being a painter (and photographer) yourself, do you think cover art adds anything to the music when it’s released?

DS: The artwork might resonate, enter into dialogue with the music, elucidate possibly? If nothing else, it can allude to the contents therein.

AAJ: Can you describe the philosophical intersection where art and music meet for you?

DS: I don’t think it is a case of one intersection, but many. Simply put, in the realm of the heart, or possibly wherever it pushes up against a truth of sorts.

AAJ: Can you contrast the creative catharsis of the finished aural product to when you finish a piece of visual art?

DS: I only feel eloquent enough in my work in music to achieve what might be called a state of catharsis. The visual work (such as it is) doesn’t function on a comparable level.

AAJ: Do you believe the evolution of digital music downloads is substantially impacting the perceived importance of album artwork?

DS: Yes, of course. But this will change and evolve in ways that will prove interesting and satisfying. I fully expect the visual component to become more elaborate, more an integral element of the entire experience. Once the physical product is all but obsolete, we will see dramatic developments in this area. The digital download also does away with the notion of format. As composers, we are now at liberty to offer up work that isn’t defined by medium, from a piece that lasts literally seconds to one that may run for hours if not indefinitely.

AAJ: Could you describe the genesis of the new record, Manafon, and the creative process?

DS: I continued with the approach that I developed on the album Blemish, which involved improvisational performances accompanied by a process of automatic writing. I expanded this approach by embracing the input of larger ensembles recorded live in studios in Europe and Japan. At the outset, I wasn’t sure if, or how, this was going to work in practice. But after the first sessions, which were recorded in Vienna in ’04, and which resulted in a number of the pieces you’ll find on Manafon, I knew I had unearthed an exchange which could yield fascinating results. That first session ran for seven and a half days. There was a lot of exploratory work done during that time.

Many beautiful improvisations were captured but, as I was looking for something specific, something I wasn’t able to verbally communicate to the musicians involved, I had to gently nudge or cajole, make hints and suggestions, bring individuals into and out of the studio so as to change the internal chemistry of the ensemble, until I finally heard what it was I was looking for. This happened on the seventh day of the sessions, the last full day of work. The ensemble at that point in time was a quartet consisting of Werner Dafeldecker on double bass, Michael Moser on cello, Christian Fennesz on guitar and laptop, and Keith Rowe on guitar. I’ve described this and the resulting work as a form of modern chamber music.

Once I knew the process worked, I gave myself less time to produce results on subsequent sessions. The Tokyo session in ’06 was a one-day affair, as was the London session of ’07. I would work on the writing and recording of the lyric and vocal melody at a later point in time, sometimes as much as a year after the initial recordings were made. This gave the writing sessions back their spontaneity and freshness, as it was like hearing the work for the first time (I’d made an initial selection of which tracks would work for me around the time the original recordings were made).

I’d play back a given improvisation and start the writing process. After a matter of hours the lyric would be complete, composed simultaneously with the melody, which locked into precise queues heard within the improvisation. I would record the vocal on the spot, meaning there was little time for revision. This is what I mean by a process of automatic writing. It was a matter of adhering to the process or the discipline and running with it until it felt complete. There’s rapidity about the process which feels urgent, decisive, and emotionally linked to the spirit of the original improv.

AAJ: What significance does the word Manafon have?

DS: I came across the word in relation to the life and work of R.S. Thomas. It’s the name of a village in Wales, the location of Thomas’ first parish and the place where he wrote his first three volumes of poetry. Over time, the word became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination, the creative mind or wellspring, hence the cover art of the CD depicting an implausible idyll, if you will. A place where the intuitive mind taps into the stream of the unconscious.

AAJ: What prompted you to incorporate free improv music again after working with Nine Horses on Snow Borne Sorrow and its sister album, Money for All?

DS: I started work on what was to become Snow Borne Sorrow prior to starting work on Blemish. Once Blemish and its accompanying tour were completed, Steve and I continued to work on the songs we’d written, and I started writing a separate set of songs with Burnt Friedman, whom I’d met on the ‘Blemish’ tour. So, over time, as has been documented elsewhere, Nine Horses came into being born out of these twin projects. Somewhere in the midst of that work I’d already recorded the first of the sessions for Manafon. So I had two separate streams of my work co-existing for long periods of time. It’s not a matter of jettisoning one in favor of the other. I didn’t see any conflict in my pursuing both avenues simultaneously. The goals we collectively set for Nine Horses differ from those I’ve been pursuing in my own work. I intend to continue to embrace this kind of diversity in my activities.

AAJ: The deluxe edition of Manafon features a documentary titled Amplified Gesture. It features interviews with people that took part in the making of the new album on the subject of improvisation. Could you talk more about it?

DS: Having completed Manafon, having spent time with some remarkable individuals who’d chosen to pursue, so to speak, the lesser trodden musical path, I thought it might be interesting, possibly important, to document these musicians in conversation speaking of their backgrounds, the relation they have with their respective instruments, what led them from one musical path to another until they found themselves working in an area which became known as free improv. An introduction to the philosophies behind the work, to the individuals behind the music. I wasn’t aware of anything comparable having been attempted, which struck me as a rather large omission. Positively neglectful, in terms of the paucity of resource material available on this subject, these subjects. I thought of it as a primer, an introduction, an invitation to delve deeper into the volumes these practitioners have produced over decades of dedication.

AAJ: Describe the overall approach you took to putting Blemish together. If the key elements to the previous record, Dead Bees On A Cake, were love, devotion and spiritual intoxication, it seems that (as stated in other interviews) the theme subjects are elements that disturb you.

DS: Disillusionment, conflict, isolation, betrayal, even going so far as hatred…you know, the whole trip!

AAJ: Please describe the conceptual contrasts between Blemish and your other solo releases.

DS: The greatest and most significant contrast might be the approach to the writing and recording of the material. This, in effect, was a simultaneous act, a series of improvisations performed over a very short space of time, which included the writing of the lyric and its performance before the ink was dry. All very much in and of the moment. Add to this the fact that I was literally, completely alone throughout the entire six-week session, and I think you might begin to comprehend the difference behind the creation of this work when compared with previous projects. Then there was the open-ended form many of the compositions ultimately took. Structurally these are very loose, never amounting to more than two chord changes per composition. Essentially (they are) drone based pieces, which allowed me to work as lyricist and vocalist in a relatively unconstrained fashion.

AAJ: How would you describe the types of stories your records tell? How comfortable are you when you have to start from your own experience and expose it?

DS: The latter lies at the heart of what I do. I no longer question the need for it. I do, however, occasionally feel uncomfortable when talking to media about the content of any given album because it is so innately personal. For someone who exposes so much of himself in his workwe’re talking nervous system rather than simply standing nakedI feel I’m allowed to throw a cloak around my daily life to protect it as much as I’m able.

I don’t know how to answer the former part of the question. Either I can’t be that objective about what it is I do, or there’s not a simple answer to that question. I’d have to go through the songbook page by page to describe the difference of approach between one set of songs and another.

AAJ: The Good Son consists of material from Blemish remixed, reshaped by other people. In the past you were unwilling to let other people reshape any of your songs (as it is usually done these days). Also, there is the Darshan (Sylvian with Robert Fripp) single reconstruction by FSOL from years ago, which was both great and unusual. What is your opinion on today’s culture, where everything is reinterpreted, reshaped and recycled? What is your opinion on the remix issue?

DS: In general, it doesn’t interest me. As you say, Virgin commissioned a few remixes of my material and I was never remotely interested in the results, with the one exception of the Wagon Christ remix of ‘Godman’ by Luke Vibert, which was a personal choice.

I don’t want to get into the history of the remix, which was largely used as a marketing tool by major labels in attempt to give an act cross-genre appeal, but as most practitioners will tell you, it was a commissioned job which used to pay ludicrously well. Maybe it still does for the few. I’ve never purchased a remix album because I’ve generally believed that the artist’s intentions were clear in the original work, and that anything thereafter was at best secondary and subject to the needs of the commercial market, at worst exploitative. I guess, in that respect, Blemish is something of an anomaly for me.

AAJ: What was the aim of the remix album?

DS: I felt that the majority of the Blemish material was infinitely malleable and wanted to see what other artists, whom I respected, would make of it. It was a means of testing the water for possible future collaborators, such as Burnt Friedman, who did a couple of remixes for me before we started writing material together for what was to become Snow Borne Sorrow. There are some extraordinary artists that really do have an inspired take on work that’s presented to them for remixing. When the remit isn’t ‘try and make this more appealing to a wider audience,’ the potential for creative results is raised considerably. Ryoji Ikeda has done a couple of remixes for me, and his take on ‘The Only Daughter’ was simply remarkable.

AAJ: How did you choose the pool of artists that took part in reshaping that material?

DS: I was already in communication with all of them for one reason or another. All potential candidates for collaborative work.

AAJ: The single World Citizen expressed your views and attitude to current world politics. Is there a political component to your music?

DS: All music is potentially political in my eyes, as to effectively act as catalyst to change in the heart or mind of an individual is a political act. Sometimes current affairs are addressed directly; at others, less so. I’m not overly fond of the use of popular song as soapbox. I tend to think that it undermines the innate power that music has to dig deep into the subconscious.

AAJ: You have been involved with many exhibitions of audio-visual “installations” or sound art, like Ember Glance and When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima. What attracted you to work in this area? Could you talk about the Naoshima work?

DS: Installation work was another arena in which to explore established interests under specific guidelines which could/should prove challenging, potentially resulting in the kind of solutions which help develop this area of work in new and interesting directions.

I was commissioned by the Benesse Foundation to produce a work for the Standards 2 festival within minutes of my landing on the island. This allowed me to explore the landscape with the possible commission in mind. The remit stated that, on reaching the Foundation’s offices, the public would be handed an iPod with which to explore the surrounding villages, museums, and ‘arthouses’ whilst absorbing the audio accompaniment. In effect, it was to be a work that tied these contrasting elements together in some fashion. I attempted to create a work that increased the awareness of other dimensions of reality whilst complimenting, contrasting, and extending the one physically at hand. A multiple exposure, a layering, mapping reference points both real and imagined. The ‘loud weather’ referred to in the title was in reference to the emotional life of the island, complimented by its spiritual ancestry and its influence on everyday life. There’s repeated reference to labor, creative endeavor, an affirmation of life or its possible futility. Then there are the associative landscapes (e.g., Monet’s early 20th century French landscape housed beneath the Naoshima soil) that pull in a wider web of connections from around the world, alluding to a greater wealth of resources and cultural exchange. Through it all blows the winds of pollination, cleansing, eradicating, alive with the voices of generations… The intention was that the audio be played at low levels so that the sounds of the environment merged with the recorded elements.

AAJ: Dead Bees On A Cake is an incredibly diverse record. Was it a challenge to make its myriad of various influences fit together?

DS: At the time I felt these compositions belonged together. They dealt with similar issues, were created in the same spirit over the same period. There was no shortage of material and, in the end, the decision as to which pieces should be included in the album appeared obvious to me. Sequencing the album didn’t prove an issue, either.

AAJ: Your interest in Eastern culture is well established and evident. Elements of Eastern spirituality are also present in your work. How closely do you identify with those traditions? Also, eastern musicespecially from India seems to be one of the most important influences on you. Which aspect of this music is the most fascinating to you?

DS: Aspects of Hinduism and Buddhism are part of my discipline/practice, so inevitably the answer has to be that I identify with these traditions in a fundamental way. I appear to have grown into them over time, though; they weren’t always an entirely comfortable fit but have become more so. I can’t say that Eastern music has a particular hold on me. I’ve been exposed to a considerable amount of Indian devotional music for the past nine years or so, and that has been absorbed and digested over time. I have enjoyed the living spirit of devotional music (in other words, hearing it performed live rather than recorded) and have been incredibly moved by it. However, it would be wrong to say that I’m drawn to this, or any music emanating from the East, more so than any other.

AAJ: How important is spirituality to you and your music?

DS: It can’t fail to be anything other than fundamentally important in life, and therefore work.

AAJ: You are heralded for your collaborative work as much as for your solo work. You worked with premier avant/jazz musicians (Czukay, Fripp, Hassell, Ribot, Sakamoto, etc.) Does working with these gifted musicians grant you a confidence that you can challenge or transcend your own capacity and ability as a composer/arranger?

DS: A challenge is a good thing and something I often request of my collaborators. Ultimately, as a composer you’re simply trying to do the work justice, nothing more. I have been fortunate, as you say, to work with talented musicians, but I tend to regard the composition as the benefactor. I’m trying to bring it alive, to give it substance.

AAJ: Your work with Holger Czukay has produced some of the most interesting ambient albums. Was there a concept behind these two albums?DS: The first of the two albums, Plight and Premonition, wasn’t planned, so if there was a concept at work it arose during the process of recording the material. Holger had invited me to Kln to record a vocal for a track he was working on. But when we arrived at the studio late that first evening, something entirely different from what had been expected took place. At the Can studio, as it then existed, there were instruments set up all around the room (an abandoned cinema). I settled down at the harmonium, I think it was, and unbeknownst to me Holger put the machines into record. And so began the Plight and Premonition sessions.

As the evening went on I recorded a series of improvisations on a number of instruments. It became clear as the work progressed that there should be little in the way of ‘performance,’ that the work should sound as though it’d been captured illicitly while the instruments themselves reverberated in that large room. Holger made a point of recording me in the process of finding myself on any given instrument. At the point that I felt I had developed something worthy of recording, the moment had already passed and we’d move on. We tried to recapture the spirit of these sessions at a later date with the recording of Flux and Mutability, but we weren’t successful in manufacturing what had been so intuitively created the first time around.

AAJ: Through the years you stretched both as an author and as a singer in various settings, genres, beyond the current trends. In general, the world at large takes electronic music far less seriously than music created for acoustic instruments. Could you please describe the balance between feeling and technology when you make music?

DS: I’m sure the above assessment no longer stands. We’ve come a long way in our embracing of electronics in music. Only a few rarified areas of any particular genre might reject electronics out of hand. On the other hand, even the most ‘natural’ of recordings uses some pretty advanced technology these days. For me, technology is a tool like any other. You work in service to the composition, whatever best serves the composition. Surely only a purist or Luddite would reject electronics out of hand. Surely all options are worth considering at the outset of a work? These become narrower as the character of the work defines itself for you in total, including its sonic identity.

AAJ: How do you look back at the The First Day experience? What are some of the sonic challenges in having to work in this format?

DS: Personally, it was getting my voice to sit well within the context of the guitar-heavy music. As you can hear, we ended up treating it a fair amount to enable it to rise above the fray to some extent. I left the sessions about one week into the recording as things didn’t appear to be working out the way I would’ve liked them. I thought it best to leave Robert (Fripp) alone at the helm for a bit. Two weeks later I returned, and a number of basic tracks had been recorded, but sonically the sound was incredibly dense, with little room for air. This fact was compounded by yet more overdubs on guitar and Stick. It took quite some work to sort the material out in the mixing stages. I was still trying to improve upon it in the mastering stage. Never a good sign, that! As for the experience overall: I really enjoyed touring with Robert. That’s where the material seemed to come alive. I thoroughly enjoyed my friendship with him. They were difficult times for us both. His presence in my life was benevolent.

AAJ: One of the past projects that I would really like to ask about is Rain Tree Crow. How do you look back on its music from this standpoint?

DS: I haven’t heard the album in its entirety since the time it was completed, but I was happy with many elements of that particular collaboration. Most of the work was born of improvisation, but much of it was worked and reworked over time, although the final recordings still contain elements, seeds of the original improv from which they grew. If personal relations had allowed, I think all involved could’ve foreseen the project developing over two or three albums, with the possible addition of live work.

AAJ: Life is full of disputes and politics, yet that friction can yield some timeless music. Does tension serve as a creative catalyst for you?

DS: I once would’ve answered this question in the negative, but I’ve embraced the conflicts in my life to the point where I’ve tried to get at the root of them in my writing, without feeling the need to provide tidy resolutions.

AAJ: Beside the two compilations, Everything and Nothing and Camphor, there were several reissues of your past solo work as well as some older material with your previous band. The additional material on the reissues is present on your boxed set, Weather Box. Since there was a lot of rumor about the re-release of this box, was this the only way to re-release the material from this box?

DS: It isn’t true to say that all of the additional material on these re-issues were present in the Weatherbox set. There’s material on the re-issues that’s available for the first time. As for the re-release of Weatherbox, this was something Virgin/EMI were interested in pursuing. I personally never thought it the right thing to do. Fortunately they couldn’t find the original artwork, so that idea was put to rest. The re-issues were always on the cards independent of the boxed set. In fact, Virgin/EMI are still talking over the possibility of creating a new boxed edition.

AAJ: In relation to publishing out-of-print materials, the bootleg community is flooded with these materials, be it video or audio. Bands have been releasing stuff from their archives (live stuff, mostly) to prevent this. Do you plan to re-release any past material video/audio/books in near future? (This refers to stuff like Preparations, Steel Cathedrals, Trophies Vol.1, Polaroids, etc.)

DS: I don’t like the idea of being forced to recycle material that has, to my mind, run its course just because the bootleg community are having a field day with it. However, if there’s a demand, and if I still feel a connection of sorts with the material, then I wouldn’t be adverse to re-issuing certain editions. No plans at present, though.

AAJ: In 2003 you founded your own label, Samadhisound. How has the label evolved from an idea to what it is today?

DS: Samadhisound came into being almost of its own volition. Running a label wasn’t something I’d anticipated as being on the cards for myself, but I’ve enjoyed my involvement in Samadhisound quite considerably. There have been periods where I’ve fought for its survival because we’d come a fair way in establishing it on a fundamental basis, and it felt premature to let the enterprise go. Having said that, we can see that the business and media are changing rapidly and that sales are in decline. If it wasn’t for the hard work of a few good people, the label couldn’t possibly have continued to exist as a platform for as long as it has. With that firmly in mind, I only look to the year ahead. I believe 2010 will see more releases on the label than in any year prior. Rather than indicating the health of the industry or label, this simply reflects the number of projects that have reached my ears that I’ve wanted Samadhisound to be a part of. As frequently said in reference to my aspirations for the label, it’s possible to plant an apple tree without harboring dreams of an orchard.

AAJ: How involved are you in Samadhi’s day-to-day business?

DS: Currently I am very hands-on in every aspect of the business. I am the engine which drives it.

AAJ: What is the artistic direction/aim of Samadhi?

DS: Samadhisound is a place both real and virtual for the meeting of minds and shared creativity. It is local and it is global, a breeding ground for ideas and new directions in music and the arts. This is one possible future for the company. I tend to believe that Samadhisound has a life of its own, aspects of which are revealed to me as and when appropriate. I tend to intuit what the next step in its development might be. I may have a personal preference for the directions it may take, but ultimately I try to listen and follow.

AAJ: One of the artists who has released an album for Samadhi is David Toop. I’m interested; what do you make of his books like Ocean of Sound, Haunted Weather or his other writings?

DS: David is one of the best writers on music that we have in this country. His works display an evolved awareness of the art of listening, which, accompanied by his breadth of knowledge of the history of different genres of music, sound art, noise, etc., informs much of what he’s published. His works are never less than fascinating, and frequently filled with penetrative insight into the sound worlds with envelope and absorb us.

AAJ: What are the main difficulties that accompany an independent label entirely devoted to experimental music?

DS: Your assumption that the label will be entirely devoted to experimental music isn’t correct. It’s my intention to release music by artists working in a variety of different genres. The difficulties, however, tend to be the same regardless of the nature of the work: how do you notify the general public of the work’s existence, and how do you get people interested enough to give it an hour of their time? If we managed to solve those issues to some extent, I think we’d be doing well.

AAJ: What have been the greatest rewards you have experienced running Samadhisound?

DS: Outside of my own work, creating the visuals for the respective releases with Chris Bigg. As art director, I locate the images and create the initial rough layout of the package. Chris then takes things a step further with the design element. Chris is a wonderfully collaborative designer. Enthusiastic, flexible, with multiple variations offered on any given idea or layout.

I’ve also enjoyed gathering together the global community of artists with which we’ve worked. In other words, I’m deeply involved in the creative side of things, and that’s where my satisfaction lies. I’m also involved in the business side of things to some extent, but the team which manage the label are trusted partners, and I’m happy to delegate responsibility in whichever department I can if I am convinced of an individual’s capabilities.