by Steven Rose for Blurt Magazine

One can draw parallels between David Sylvian’s career and that of Scott Walker.

Sylvian, who at age 51 is 15 years younger than Walker, also experienced early success as a handsome British pop idol – his New Romantic/New Wave band Japan enjoyed a series of Top Ten hits in the early 1980s, one of which, “Ghosts,” was remarkable for its ambient soundscape. Like Walker, Sylvian has a gorgeously smooth, sensuous voice – in his case, a tenor (that seems to have deepened into baritone) with a yearningly intimate vibrato.

And after Japan, from the 1980s onward, Sylvian, like Walker, has moved steadily toward the avant-garde side of pop music with his lyrical and instrumental concerns, alone and with international collaborators.

And both men have adopted new homelands – while Walker left his native U.S. for Britain back in the 1960s, Sylvian in the 1990s left Britain for the U.S. to pursue sadhana, enlightenment through the aid of a spiritual guru, first in Northern California and then New Hampshire. Divorced, he now spends time between New York City and New Hampshire, where his children live.

“For people who leave their native country, you begin to feel you can’t put roots down anywhere else and yet you can’t go home because the place you left no longer exists as it once was,” Sylvian says, in a telephone interview about the release of his new album Manafon. “In a sense, the world becomes your home because one place doesn’t feel like home any more than any other. Yet there’s a freedom in that opening. Something is lost but something is gained.”

Both men, in short, have become deep-thinking aesthetes. Yet if there’s been a major difference, Walker’s music increasingly has tried to match the despair and darkness of his subject matter. Albums like Tilt and The Drift are tough conceptual art. Sylvian, on the other hand, especially in his highly lauded 1999 album Dead Bees on a Cake, had been trying to find breakthrough beauty that contains a spiritual dimension – not conventional prettiness or religiosity, by any means.

He’s become one of pop music’s great seekers.

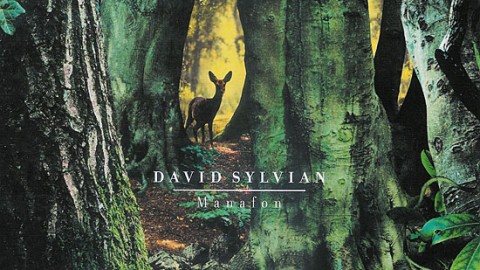

Manafon — named for a Welsh village and released on his own Samadhisound label – continues his search for peak musical beauty, in many ways. But the darkness that is life is starting now to surround him.

Working with improvisational musicians over the course of several years at sessions in Vienna, Tokyo and London, he has created nine songs featuring hushed and muted soundscapes: breathy, restrained sax; careful guitar strumming; isolated cello shrieks; short, high-octave piano explorations; quietly commanding acoustic bass; occasional live electronic interventions or turntable scratches, and other sounds. Musicians include Evan Parker (sax), John Tilbury (piano), Werner Dafeldecker (acoustic bass) and Franz Hautzinger (trumpet). Sylvian relies on his voice, both soothing and foreboding, to provide the melody; the songs are all ballads, slowly and ruminatively sung with lots of space between words.

But those words. For a man who seemed on the verge of achieving bliss on Dead Bees’ “Krishna Blue,” these lyrics often feel ominous. From “Snow White in Appalachia”:

“There is no Maker,

just an exhaustible indifference/

And there’s comfort in

that so you feel unafraid.”

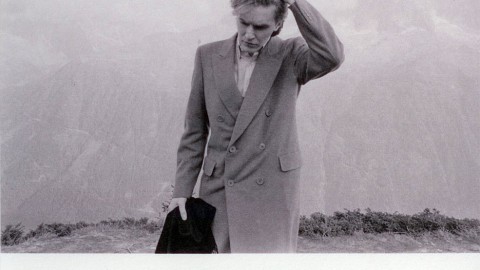

“Random Acts of Senseless Violence,” which may be about the all-too-temporal scourge of terrorism: “The safety in numbers is just a contrivance/For the future will contain random acts of senseless violence.” A song called “The Rabbit Skinner,” which ends with Sylvian concluding “Here lies a man without quality,” has extra bite because the album comes with a portrait of a weathered Sylvian holding a dead rabbit.

Sylvian used a process known as “automatic writing” in coming up with the lyrics. He had done that earlier with 2003’s Blemish, an at-times difficult album at least partly about his divorce. On Manafon, he was responding to the music that had (mostly) been previously recorded, sometimes a year ago or longer. It wasn’t completely spontaneous; he listened to the music studiously to find words that he believed organically fit the instrumentation. And he occasionally used notebooks to help when he became blocked.

But he also let his own words surprise him, not editing or rewriting them for poetic cleverness.

“I wanted to get to a certain subject matter that seemed unreachable, out of my grasp,” Sylvian explains, in a voice both erudite and confessional. “I wanted to push myself to those areas and see what would surface. In automatic writing, there’s not really a point where one reviews what one has written prior to recording it. [There’s] a sense of possible revelation that can be quite exciting, because what’s revealed publicly is also revealed to myself.”

So what’s being revealed? One comes up against a crisis in faith, a mourning for life as lived and its limits. It’s especially striking in that previously quoted line from “Snow White in Appalachia” – a beautifully haunting song that seems like a wiser, more sorrowful cousin to The Stones’ “Moonlight Mile” – about the absence of a “Maker.”

“I’m not afraid of complete annihilation,” Sylvian says. “I don’t have a problem with this life being all there is, that things come to a full stop at the end of a lifetime. In fact, I find it quite comforting to think along those lines. I find it a beautiful thought that life can go on, but there’s no knowledge of what that life will consist of. Does the suffering of this life also go on into the next, as well as the joys?

“Now my brother, who’s an atheist, finds that quite troubling, so we’re kind of at odds with each other. He would love to believe that life goes on. He loves life so much he wishes it were eternal.”

In a way, perhaps, Sylvian is where Peggy Lee was at when she sang Leiber & Stoller’s “Is That All There Is?” back in 1969, but maybe not as resigned to it as she. “This whole album, in one sense, deals with disillusionment,” he says. “I think this is just where I find myself at this particular moment. It’s very much a document of a moment in time.

“There are a lot of questions that show up in the course of writing the work, but there is no resolution because I had no answers at the time. Usually I write from the standpoint of having lived thru an experience and then I feel comfortable to write about it. I haven’t been doing that so much. I feel more comfortable with the process of questioning and not knowing.”

As Sylvian describes it, his long, devotional search for sadhana lately has been meeting with obstacles. That’s not an unheard-of thing; sometimes an obstacle is meant to test someone and show a greater truth. But, he says, he can’t get around this one.

“I came up against one of these obstacles and I found myself incapable of getting around the thing,” he says. “So I started to look at what was being shown to me, but I couldn’t grasp the nature of the lesson. That’s where I find myself. At the same time, my means of trying to comprehend it are part of my development.”

Asked what specifically that obstacle is, Sylvian demurs. “That’s a kind of personal issue I don’t feel comfortable talking about directly,” he says, with a tone of apology.

On the flip side, Sylvian notes, there’s a positive side to Manafon. “It’s dealing with the poetic imagination, the creative mind, which is enormously powerful and in some way is connected with the core of our being. If a life is given shape by one’s poetic acts, I think there’s great beauty to that and great significance to that.”

So Sylvian’s struggle continues – as does his art.

Original article on davidsylvian.com