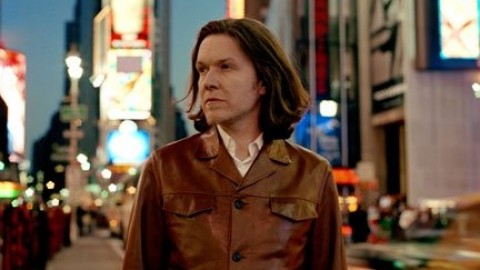

In Spike Magazine, Darren J.N. Middleton talks to David Sylvian about the search for truth, meaning and transcendence.

I: Adventures of the Spirit

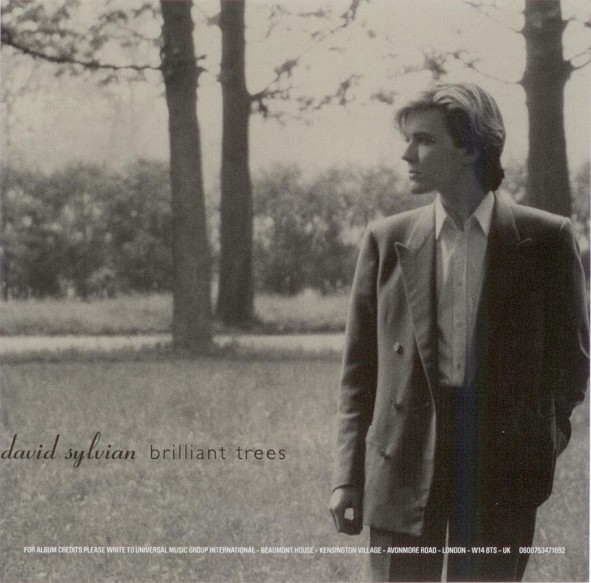

Born in England in 1958, David Sylvian first hit the British music scene in the late 1970s with Japan, one of several bands that defined the so-called New Romantic cultural period. He later scored a UK Top 5 hit with ‘Ghosts’, before turning solo in 1982. The last 20 years has seen him collaborate with music’s great and good – Ryuichi Sakamoto (Yellow Magic Orchestra), Holger Czukay (Can), and Robert Fripp (King Crimson) – but, to many, his own work represents his best efforts, and repays the closest attention. In the words of Martin Power, his unofficial biographer, Sylvian has crafted “some of the most touching ballads of the pop era, ballads that bring something out in the listener; at worst, sorrow, at best joy” (2). Far from cloyingly sentimental, Sylvian’s songs reflect a deep and abiding sense of the sacred eternally renewed in the common. And they have earned for him a reputation as an artist whose work displays rich religious resonance. Albums such asBrilliant Trees (1984), Gone to Earth (1986), Secrets of the Beehive (1987), Dead Bees on a Cake (1999) and, more recently, Blemish (2003), have cemented this reputation (3).

Sylvian crafts music around his most religiously existential thoughts and feelings. And inwardness is fundamental to this task, he has said, for only we can ask, Who am I? No one else can make this special journey, only the self. Along the way, Sylvian has developed this approach to his life and work by seeking out and drawing upon eclectic influences – everything from the historic Buddha to Gnostic Christianity, from the painter Frank Auerbach to the sculptor Joseph Beuys, and from the poet W.B. Yeats to the Hindu visionary Mother Meera. Without a doubt: Sylvian embodies an energetic, hybridized spirituality, and the burden of this essay is to track and note some of the major signposts on his ongoing pilgrimage.

By all accounts, Sylvian’s religious questioning began very early. At the end of Japan’s tenure, for example, he had not only lost faith in pop stardom, he was beginning to feel displaced spiritually. We hear him lament in ‘Ghosts’: “Now I find myself alone / The simple life’s no longer there / Once I was so sure / Now the doubt inside my mind / Comes and goes, but leads nowhere” (4). Paradoxically, this period of doubt created space for a steely resolve to leave the band and embark upon a solo career, where he sustained his initial self-scrutiny through songs like ‘Forbidden Colours’. References to “the blood of Christ” abound in this track, but other lines uphold the scepticism expressed throughout ‘Ghosts’: “I’ll go walking in circles / While doubting the very ground beneath me / Trying to show unquestioning faith in everything” (5). Not surprisingly, he felt alone, even abandoned: “Grieving for the loss of heaven” (‘Weathered Wall’) created a “certain difficulty of being” (‘Red Guitar’) for Sylvian – and “a reason to believe / divorces itself from me.” (‘Brilliant Trees’) (6).

Slowly, imperceptibly, things began to change. The light dawned. And an unrecorded song, ‘Nagarkot’, reflects what we might call – using a Buddhist phrase – his vimuti, his secret of release:

Beyond all doubt there is a place

That place

Vast rivers, tall mountains

Tiny boats

Some old and forgotten

Some making their way for the very first time

Across the mischievous ripples of the yawning deep

I stand quietly on a hill top (Nagarkot)

Waiting for stillness

Calm

That I too may make the journey

That long and perilous journey

Hard nails, oak wood

And a heavy heart

Home. (7)

Sylvian’s second vocal album, Gone to Earth, explored this sense of release. “But I’m no longer lost,” he declares in ‘Laughter and Forgetting’, “Every day, every second, every hour inside / Love’s my own guide” (8). And in ‘Wave’, he speaks of “a strength inside like I’d never known” – the courage, that is, to step into the unknown, looking not for assistance to anyone besides the self (9).

Secrets of the Beehive, Sylvian’s third solo album, appears to have surfaced either just after or during an intense period of pensiveness linked to his then increasing interest in the Soto school of Zen Buddhism. That was in the mid-1980s. Very generally, Soto’s salient features include the practice of (i) meditative sitting (zazen), usually in a temple, one perhaps surrounded by a garden, so the meditating self can feel connected to nature, and of (ii) reflecting on riddles (koans) that free the self from desire and allow it to find inner peace, to blossom. Often viewed as one of the most ascetic forms of Buddhism, Soto disfavours elaborate worship and detailed ritual; instead, it stresses just sitting and paying close attention to the self’s total personality (10).

Sylvian found himself attracted to Soto Zen because, by the mid-1980s, he had arrived at a point where he valued religious introspection. And he was concerned to strip himself of all artifice. He felt himself drawn, in other words, to something dogma-free, something structureless, leader-free, and spiritually simple – hence: Soto Zen. By seeking to know the inner meaning of things, the Soto Zen Buddhist believes that the self gains perfect wisdom directly, without the need for those teachers who claim to point the self to the answers to life’s questions and problems. Significantly, this approach dovetails with Sylvian’s own sense, explored throughout Secrets of the Beehive that the self remains blindsided by unreality and ignorance, alienated, devoid of a center that holds, until it becomes a lamp unto itself. As he sings in ‘Orpheus’: “Sunlight falls, my wings open wide / There’s a beauty here I cannot deny” (11). With this third album, then, Sylvian took refuge in his own, thorough survey of the self’s discriminating Mind (12).

Sylvian’s adventures of the spirit did not stop there, however, for his 1992 marriage to Ingrid Chavez, an American singer/actress, brought him to full awareness of a new fork in the spiritual road. By all accounts, she encouraged him to explore his religious formation through the Hindu Vedic scriptures. Together, they focused on the Upanishads, orVedanta (“end of the Vedas”), which must be seen, I think, as offering Sylvian something different religiously. I say this because the basic feature of Vedanta is the notion that spiritual truth is not found through a process of individual inquiry, as with Soto Zen Buddhism, but by filial devotion and surrender to a spiritual master, or guru.

Then, as now, it is Mother Meera who served as Sylvian’s guru. Associated with Thalheim, a small village located in the German countryside, she is a renowned Hindu mystic – and people of all religions, creeds, nationalities, and races make pilgrimages to see her (13). Sylvian is no exception. And in ‘Thalheim’, a track from his fourth vocal album, Dead Bees on a Cake, he captures the intense, sublime moment when he first experienced Darshan(‘view’ or ‘revelation’) during an audience with her:

Take the shadow from the road

I walk upon

Be my sunshine, sunshine

And in the emptiness

You look and find someone

The damage is undone

And love has made you strong

Heaven gave me mine

Thalheim. (14)

Secrets of the Beehive is an album marked by a lone seeker’s private quest for salvation from the grief-stricken state of personal alienation. But Dead Bees on a Cake leaves this approach behind, offering in its place the way of self-surrender as a means of experiencing divine grace and help. Themes of solitude give way to focused faith, then, and insight yields to devotion. Not surprisingly, Mother Meera stands at the centre of this deeply deconstructive-reconstructive process. As Sylvian sings in ‘I Surrender’:

I’ve traveled all this way for your embrace

Enraptured by the recognition on your face

Hold me now while my old life dies tonight and I surrender

My mother cries beneath the open skies and I surrender. (15)

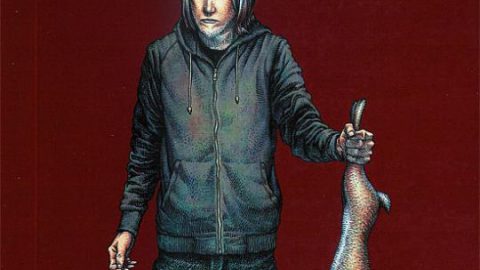

Surrender appears to have led Sylvian to adopt a regular religious practice of devotion (bhakti), resulting in songs like ‘Krishna Blue’ (Dead Bees on a Cake), ‘Cover Me With Flowers’ (Everything and Nothing compilation), ‘Snakes and Ladders’ (published poem,Trophies II), and in ‘Living in the Land of the Blue-Skinned Gods’ (from his recent ‘Fire in the Forest Tour’, 2003). These days, Sylvian seems comfortable walking the devotional path, although some critics might say that Blemish, his most recent album, marks the sudden return of the anguished, embittered soul who narrates Secrets of the Beehive. It is too early to tell.

In my view, all signs appear to indicate that Sylvian has learned to coagulate different elements of Buddhism and Hinduism within himself. Like so many postmodern souls, that is, he upholds an existential, religious hybridity built around a transcultural amalgam of influences – a point that comes out all-too readily in the following interview, which Sylvian agreed to give in November 2003.

Here Sylvian answers questions about the origins and shape of his religious views. And what emerges from this exchange is an extraordinary picture of an intensely spiritual seeker, a deeply devout man whose art poses those questions whose answers do not come easily, if they come at all.

II: Artistic and Religious Hybridity

DJNM: I wonder if I might set the scene, as it were, by asking you to look back over your life thus far and then outline the contours of your spiritual journey to date?

DS: I don’t think all of the elements that constitute a spiritual journey are necessarily obvious. Childhood influences must play a major part in one’s development but how to pinpoint them? There’s the issue of environment, key moments of revelation, epiphany, disillusionment, insight, intuition, habits, and fears. All appear to play a part in a mind eager for clarification, inspiration, or simply confirmation, going some way towards justifying the intuited awareness of another reality that isn’t being owned up to or catered for in the immediate environment or even in the world at large outside of organized religion. I’ve always carried with me a faith of sorts, born out of all the above influences and more. This faith, unshakable as it was, wasn’t really questioned in any depth until I’d made it through my teenage years. I then questioned every aspect of what constituted my faith. This was a period of upheaval that I embraced with something akin to relish. A casting out, doing away with any aspect of my life that didn’t bear up to close scrutiny. This search led me to look into Gurdjieff’s teachings, Sufism, Gnostic Christianity, and Buddhism etc. At some point or another all of the above held me captivated for a period of time. My faith was restored to me stronger than ever before without the basis of a given set of parameters, without dogma. I was free. I felt free to explore whichever avenue of interest cast its spell and, more importantly, produced results. For me, Buddhism held the most persuasive deck of cards. This was the source of knowledge that informed my practice for a number of years without the benefit of a personal teacher. This was ultimately to prove problematic as the practice itself became quite dry and uninspired. At that point I actively searched for a teacher. Surprisingly, this search led me to series of teachers out of India whose background was Hindu based. Although I was never told to redirect the focus of my practice, I slowly began to glean the significance, decode the meanings behind the technicolor images of Hindu gods and goddesses, some astoundingly gory in their representations, and was drawn into this enticing world, fascinated by the practices, the devotional aspect of the worship, and the, to my mind, indisputable wisdom of the Vedas.

DJNM: I want to focus on ‘Forbidden Colours’ for a moment. This is one of your early solo recordings, of course, and here you craft and deliver a lyric with multiple Christian allusions. I also note your use of an envelope structure that begins with a plea for belief and ends with the beginnings of belief. Generally speaking, what were your thoughts about Christianity as you approached the writing and recording of this song? Do any of these thoughts remain with you today? If so, what are they? If not, why not?

DS: The song was written during the period I just described where faith itself was under scrutiny. Having been brought up in Christian based schools where classes such as ‘scripture’, in which the bible was read and studied, were mandatory, my belief system naturally had a Christian bias or cosmology. As the subject of Christianity itself was under scrutiny my writing pursued this enquiry also. The lyric deals with the loss of faith, doubt, suffering, and divine love. Although I’ve performed the song live in recent years I’ve had increasing trouble connecting with the piece on a profound level. I believe this is attributable to that fact that a) the Christian symbolism of the piece no longer holds any real significance for me and b) the issues that arise in my practice are no longer to do with a lack of faith. The notion of a distance from the divine “a lifetime away from you” doesn’t hold true for me at all as I know that the divine is available to us in the here and now. It isn’t something attained at the time of death.

DJNM: In retrospect, what, if anything, is the “new religion” alluded to in ‘Pulling Punches’, featured on your first solo vocal album, Brilliant Trees? A related question: What definition and/or meaning would you attach to the word ‘religion’?

DS: “New religion” would be a reference to the hybrids that surfaced with the advent of the New Age movement. Beliefs systems that had gone through something of a filtering process removing all the fat and therefore any potential benefit. A religion that by defaults pulled its punches. Religion: a set of beliefs, practices, and disciplines based on a defined set of human and spiritual values, informed by the wisdom of its literature as recorded by its prophets.

DJNM: References to “age of reason,” “nausea,” and “iron in my soul” in some of the songs that appear on Brilliant Trees invite comparison to Jean-Paul Sartre. Is there anything in this comparison? If so, do you think Sartre’s views on religion are ultimately positive or negative?

DS: My memory of the Sartre books I have read is sketchy at best. I believe the reason for this is that I was ultimately unimpressed by Sartre’s philosophizing. However, insightfulness into the human condition as revealed by contemporary philosophers and writers is relevant and beneficial when diagnosing the inherent problems therein. There is a practice in Tibetan Buddhism based on debate. The basics of the practice are under attack from the practitioners. This is because a system of belief must hold up under severe scrutiny. It must also produce results. Insightfulness into human nature, and the critical dissection of its beliefs are, I believe, signs of a healthy society.

DJNM: As you know, your song ‘Weathered Wall’ alludes to Jerusalem’s Western (sometimes: wailing) Wall. Have you ever visited the Holy City? If so, what were your impressions? Also, the protagonist in this song sings: “Grieving for the loss of heaven / Weeping for the loss of heaven”. The same could be said of the protagonist in your song ‘Brilliant Trees’: “A reason to believe / divorces itself from me”. Do such lines hint at a loss of faith on your part, perhaps even a deconversion from a previously held or assumed belief?

DS: I have never visited Jerusalem. Again, the album Brilliant Trees was written in a period when my belief system, my faith, came under attack. I wanted to see what remained when all pillars of support were removed. The pieces you mention are explorations along those lines. The narrator of Brilliant Trees ultimately finds redemption in human love, which for him is linked to the divine.

DJNM: A sense of peaceableness comes through in one of your unrecorded songs, ‘Nagarkot’. In fact, the title, unless I am mistaken, refers to a Nepalese hilltop “beyond all doubt” and that, from here, your protagonist – you? – plans to proceed out on a “long and perilous journey”. Where or what is Nagarkot to you? Does it play any kind of role in your spiritual formation?

DS: The poem was written in response to a trip to India and, more importantly, Nepal back in ’84. Seeds were sown that gave me a philosophical grounding of sorts and a renewed sense of spiritual well being (Nagarkot).

DJNM: Your second vocal album, Gone to Earth, hints at a kind of pantheism, or at least suggests that you are trying to integrate the sacred and material world, lyrically speaking. Is this a fair observation?

DS: Fair enough. It is relatively difficult to write about matters of a spiritual nature in popular music. There are many obvious pitfalls. I attempted to focus on love, to merge the experiences of love, human and divine. This created an ambivalence that allowed for multiple readings. I was also somewhat enamored with the Gnostics at this point in time, hence the embracing of some of their symbolism.

DJNM: ‘Lilith’, another unrecorded song, seems replete with ancient and modern allusions and symbols: Lilith, of course, is a feisty woman in ancient Hebrew tradition; shamans are religious specialists; “the will to power” is the title of a book by Friedrich Nietzsche; and, finally, “the holy blood of saints and sheep” suggests martyrdom or else ritual offering. Religiously speaking, what were you trying to accomplish with this song?

DS: The piece certainly appears symptomatic of the eclectic nature of the search for truth and meaning. I have little recollection of the lyric but I’d attempt a definition as “the power of divine energy embodied in human form. The realization of humanity’s potential and/or destiny”.

DJNM: Secrets of the Beehive, your third vocal album, is also riddled with religious references. Many appear to evoke Christian symbols, ideas, and themes. What does the Cross (‘September’) mean to you, for example, and how do you understand talk of Kingdom (‘The Boy with the Gun’)? Do you, personally, believe in a devil, for example, or do you deny the devil’s existence (‘The Devil’s Own’)? What place has Jesus in your spiritual journey (‘Mother and Child’)?

DS: The Christian symbols no longer have any hold on me. I could speak in the past tense but I don’t feel my interpretations of these references differ from most. The point of using them in this context is a short hand of sorts. I don’t believe in a devil. I do believe in the force of evil, I believe in the force of love. Heaven and hell are here and now, defined by psychological states. We know what hell feels like. We experience on occasion our descent into it. Most of us are fortunate enough to re-emerge. Likewise we also experience heaven by degrees and intensity.

DJNM: Other recordings from the Secrets of the Beehive sessions, such as ‘Promise (the Cult of Eurydice)’ and ‘Ride’, speak of angels, chapels, rosaries and ravaged souls. After these songs, though, I sense a paradigm shift, for you appear to leave behind the subtle Christian references, and, as we now know, you change direction and begin invoking Shiva, a member of the Hindu pantheon, and Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, also a member of the Hindu pantheon. Spiritually speaking, did you experience a new ‘ashrama’ (stage of life) after recording and promoting Secrets of the Beehive?

DS: The period following on from Beehive was the hardest of my life. That descent into hell I spoke of. Great mental suffering. Yes, what felt like a monumental shift in awareness and development took place after four years of darkness. This was a darkness in which, although denied light, I never lost awareness of the light that underpins all existence. It was at this stage, after numerous attempts had been made to understand the nature of the experience I was going through (including a beneficial period of psychoanalysis), that I found the first of my teachers, hence the shift in iconography, which you correctly point out. Prior to this period though was the Rain Tree Crow project (ed: Sylvian reunited with the former members of Japan). This is an important document for me as it denotes the end of many intimate relationships, including my association with Christianity: “I touched his hand / it burned like coal / I put paid to the devil / and I saw the mountain fall / Fall on” (ed: this is from the song ‘Every Colour You Are’).

DJNM: Dead Bees on a Cake, the long-awaited follow-up to Secrets of the Beehive, showcased Hindu and Buddhist themes. And for many of your listeners, it helped to put Thalheim on their cultural map. What does Thalheim mean to you? When did you make the pilgrimage there, and what did you discover?

DS: I visited Thalheim for the first time in ’92. Oh god, what did it mean to me? It was the beginning of the journey in earnest. It was the rebirth of love. I can’t do better than that, I’m afraid.

DJNM: Have you ever visited India? If so, what were your impressions, religiously speaking? In America, do you have any contact with the Indian diaspora?

DS: I have visited India. I lived in an ashram during my second stay there. I think it’s fair to say I have only experienced India in the religious sense. India is after all a religious experience. I do have peripheral links to a part of the Indian community here in the States, courtesy of my guru, but I wouldn’t want to overstate that.

DJNM: How important is mindfulness to you? What place does it have in your overall thinking about yourself?

DS: It plays a role of great importance in my daily life, although like most aspirants I fall short of my own expectations in this respect.

DJNM: Do you believe there is no self? If so, are you comfortable with saying that people are collections of different perceptions in flux? If not, how would you define the idea of ‘no self’, and how does this idea shape your views on morality, for example, and moral responsibility, or life after death?

DS: The ego is an illusion. Absolutely. Your second statement strikes me as too general even if true of the mind. It doesn’t help me to view life in this respect. Once we have created a basis, a foundation of love and compassion from which to work (heart over mind) we can view the world with greater understanding. Understanding something intellectually (mind) and experiencing it as truth (heart) are very different things. Once an experience of the truth has been attained then the last part of your question is answered intuitively. Not a question of moral or immoral but a question of truth. Truth as experienced, not as intellectual conception. ‘No self’ is for me an act of surrender. This act is a form of meditation that is reaffirmed with every breath. I don’t think in terms of life after death. There is only life.

DJNM: Some might say that ‘God’ is an oversoiled word. How do you respond to this remark? And how, if at all, do you give meaning to this word?

DS: It’s difficult for us to embrace the formless, we who have taken form. For some it’s possible but for most of us a more suitable path might be one of devotion. The nurturing of love above and beyond oneself. Our focal point might be a mountain, a tree, or a more traditional embodiment of divinity such as Christ, Krishna, and Buddha etc. However, in the final stages of realization even the concept or form of god must be relinquished. Ultimately there is only the formless consciousness. Divine love. God is a loaded word. It is high time for a new vocabulary with which to maintain this dialogue on the spiritual.

DJNM: Do women and men have all the potential they need in themselves to make sense of and live out their existence, or is the truth’s source in a higher, transcendent realm of meaning?

DS: We exist in that higher realm of meaning but we remain ignorant of it. It is the goal of this journey to recognize and experience this truth. Ultimately, yes, we are That.

III: Encore

We would do well to note that David Sylvian came of age in the midst of an event that British sociologist Callum Brown calls the “death of Christian Britain” (16). Educated in an English comprehensive school marked by a core curriculum commitment to basic literacy in Britain’s Judeo-Christian heritage, the teenage Sylvian read the Bible during his R.E. lessons. However, he never really resonated in that harmonic way with its stories. Scripture simply failed to add a string in the upper or lower register of the instrument within Sylvian that thrums, spirituality speaking. In later life he raided this religion’s particular symbolic storehouse, as we have seen, but he never converted to Christianity, electing instead to travel the world and witness firsthand how non-Christian religions answer life’s questions.

Sylvian encountered aspects of Buddhism and Hinduism during his numerous tours through Asia with Japan. (Nepal was especially transformative, as we have seen.) And after he left the band to embark upon a solo career he read works by artists and thinkers as diverse as J.G. Bennett, Jean Cocteau, and George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff, thus creating within himself a site of contested religious interpenetration. Additional travels and further reading have only intensified his urge to renegotiate and redefine seemingly dissimilar beliefs, behaviours, and styles. Sylvian’s time in America, as previously mentioned, appears to have changed him in significant ways. In the last decade, Sylvian has lived in Minnesota, California, and, most recently, in New Hampshire. And his latest recordings not only showcase his devotion to Vedanta, which his American wife has helped him with, they demonstrate his real passion for a range of hitherto unexplored American musical impulses – everything from New Orleans Jazz to Clarksdale (Mississippi) Blues. He seems to have discovered, in other words, how to blend different spiritual and aesthetic influences within his own, often-beleaguered soul. In light of such cultural malleability, I suggest that Sylvian symbolizes what American sociologist Robert Wuthnow terms “creative spirituality” – a 21st-century trend that stands poised to revitalize American religion (17).

Wuthnow’s last three books – After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s(1998); Creative Spirituality: The Way of the Artist (2001), and All in Sync: How Music and Art are Revitalizing American Religion (2003) inspire my suggestion. In After Heaven, Wuthnow uses different types of sociological material to describe how Americans have recently moved from a “dwelling” spirituality to a “seeking” spirituality. Dwellers embody a strong sense of family and community, find security in faith placed in denominations or institutions, uphold tradition, and think of the sacred as most present to them in consecrated buildings. Seekers, however, value personal pilgrimage, individual spiritual evolution, and frequently negotiate their belief and behavior in light of the rules and regulations associated with more formal, institutional religious groups (18). Dwelling and seeking are like two variables in Hegelian dialectic, according to Wuthnow. They are, he claims, like the thesis and antithesis that come together and do not so much combine as reappear on another level, the level of “spiritual practices.” And spiritual practitioners are unlike dwellers and seekers because, religiously speaking, they value both the safe harbor where they can drop anchor and the wide open sea upon which they can sail; in short, they crave security as well as adaptability. These days various and diverse spiritual practitioners dot the American religious landscape. Such people are entrenched in tradition yet often find themselves reaching for new possibilities, Wuthow observes (19). Many are self-consciously pluralistic, some see themselves in transcultural or transnational ways, and almost all recognize both music and art’s vital role in the development of twenty-first century American religion. Creative Spirituality and All in Sync discuss this last item extensively, and together they provide a useful lens through which to view Sylvian’s religious vitality and hybridity (20).

Wuthnow makes at least three major observations in these two books. First, he claims that contemporary American spirituality focuses on the sacred’s ineffability. God is always more than what one can say about God. And several artists, artists Wuthnow profiles – such as Madeleine L’Engle, Tony Kushner, Andres Serrano, Greg Wyatt, Carla DeSola, and David Ellsworth – uphold this sense of divine mystery. For their part, many ordinary Americans now doubt dogma’s ability to define the sacred. According to Wuthnow they question reason, eschew metaphysics, and disfavour ontology. Indeed, Wuthnow shows how many ordinary Americans are now taking their religious cues from singers, painters, novelists, playwrights, photographers, sculptors, dancers, and wood carvers – creative women and men who, like Sylvian, uphold an intuitive approach to the divine through their imaginative use of myth, symbol, and imagery (21).

Second, Wuthnow observes that many artists create from personal struggle. And he notes that many Americans now seem to thrum to contemporary art-with-sacred- themes because they sense a harmonic connection between their life’s journey – tragic childhoods, broken relationships, destructive patterns of behavior, 12-step programs, career disappointments, et cetera – and their favorite artist’s own anguished pilgrimage. In their quest for meaningfulness, then, ordinary Americans are now turning to artists for assistance (22).

Third, Wuthnow demonstrates that America’s own emerging ethnic, social, and religious diversity shapes the aforementioned artists and the assistance they offer to ordinary Americans. Today, it is almost impossible to visit cosmopolitan cities like New York or the rural heartlands of Kansas without encountering diverse people, mainly immigrants, who have brought a new texture to American religious life. Immigrant religion is transcultural, transnational, or syncretistic religion. And these days artists are making full use of immigrant religion’s many multihued and stimulating stories, incorporating them into their art, and then offering the result to a public keen for help in their quest for meaning (23). In my view, David Sylvian’s music reflects this cultural ferment within contemporary America.

From his new Stateside base Sylvian affirms divine mystery, especially in his interview’s clarion call to re-expand those boundaries we have placed around God. His own pilgrimage, moreover, testifies to personal struggle; as a result, he forges art on life’s hard anvil. Fans often say that his lyrics and music gesture toward transcendence and stimulate interiority. And many claim that they have gained clarity about their own faith journeys by considering Sylvian’s own (24). He is like so many of the artists Wuthnow has in mind, in other words, artists who are coming increasingly to help scholars, religious leaders, and ordinary believers focus on the imagination’s vibrant role in religious and theological construction. (25).

Department of Religion, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX 76129, USA

d.middleton2@tcu.edu

References

1. This interview was conducted via email, November 2003. I am grateful to Mr. Sylvian for his time, energy, and unqualified permission to quote from his published lyrics and poems. For this material, I use Trophies I: The Lyrics of David Sylvian (London: Opium [Arts] Ltd., 1988) and Trophies II: The Lyrics of David Sylvian (London: Opium [Arts] Ltd., 1998). In addition, I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Mr. Richard Chadwick, Opium (Arts) Ltd, for facilitating the interview. I also appreciate the help of Kieron Lawlor, Gerry McConnell, and Jeryl Pohl.

2. M. Power, David Sylvian: The Last Romantic (London: Omnibus, 1998), pp. 188.

3. I plan to focus on Sylvian’s vocal albums only. Other critics have explored the link between his instrumental work and his spirituality, and I direct the reader to their work. M. Power discusses Sylvian and Shamanism in his book. See The Last Romantic, pp. 114-15.

4. Trophies I, p. 11.

5. Ibid., p. 13.

6. Ibid., p. 19, 20, 23.

7. Ibid., p. 25.

8. Ibid., p. 29.

9. Ibid, p. 35, 39.

10. G.E. Sainte-Laurent,. Spirituality and World Religions: A Comparative Introduction(Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing, 2000), p. 195-227.

11. Trophies I, p. 51.

12. More recently, Sylvian has called his own record label Samadhisound – and samadhimeans, roughly, ‘spending time in meditation’. For additional information, see davidsylvian.com. Samadhi also refers to the meditative position – sitting with legs crossed and balanced, arms extended and relaxed, and eyes closed or half- closed, focused – adopted by the historic Buddha, and by Buddhist devotees.

13. For additional information, see http://www.geocities.com/ganesha_gate/meera.html. Also see M. Matousek, “Darshan with Mother Meera,” in S. O’ Reilly and J. O’ Reilly, eds.,Pilgrimage: Adventures of the Spirit (San Francisco: Travelers’ Tales, 2000), p. 51-67.

14. Trophies II, p. 49.

15. Ibid., p. 47.

16. C. Brown, The Death of Christian Britain (London and New York: Routledge, (2002).

17. I use three Wuthnow texts throughout this section. R. Wuthnow, After Heaven: Spirituality in America Since the 1950s (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California P, 1998); Creative Spirituality: The Way of the Artist (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California P, 2001); and, finally, All in Sync: How Music and Art are Revitalizing American Religion (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California P, 2003).

18. After Heaven, pp. 1-51, 142-67.

19. Ibid., pp. 168-98.

20. Wuthnow does not mention Sylvian.

21. All in Sync, pp. 21-55.

22. Ibid., pp. 79-133. Also see Creative Spirituality, pp. 266-76. Wuthnow is hardly alone in this observation. See R. Coles, Bruce Springsteen’s America: The People Listening, A Poet Singing (New York: Random House, 2003).

23. All in Sync, pp. 8-20. Also see Creative Spirituality, pp. 64-70, 101-12, 181-93.

24. Numerous websites, discussion boards, distribution lists, and blogs support this claim.

25. All in Sync, pp. 183-212.

Original article on Spike Magazine