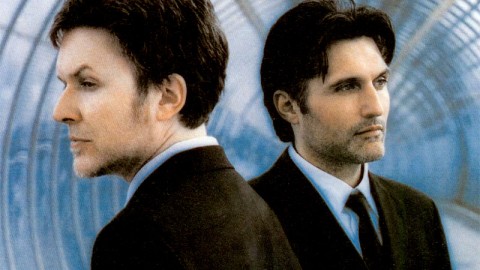

Nine Horses is David Sylvian’s new incarnation. By Michael Dwyer.

December 30, 2005

Nine Horses is David Sylvian’s new incarnation. By Michael Dwyer.

Royal Albert Hall, London, 1993. David Sylvian’s flamboyant electronic band, Japan, was 10 years dead and his latest project with King Crimson guitar brainiac Robert Fripp had turned into a rather more challenging night out.

Happily, there was one other punter hiding in the palatial men’s room of the venerable concert hall. Not my cuppa tea, he said. So why was he here? Old acquaintance. I used to do his old band’shair.

Sylvian almost drops the phone laughing. He has no idea who the chap may have been – Japan had a lot of hairdressers – but he digs the metaphor: pop stylist unimpressed by former model’s arty new direction.

Nine Horses is the latest project in an often experimental, seldom laughable career spanning 30 years.

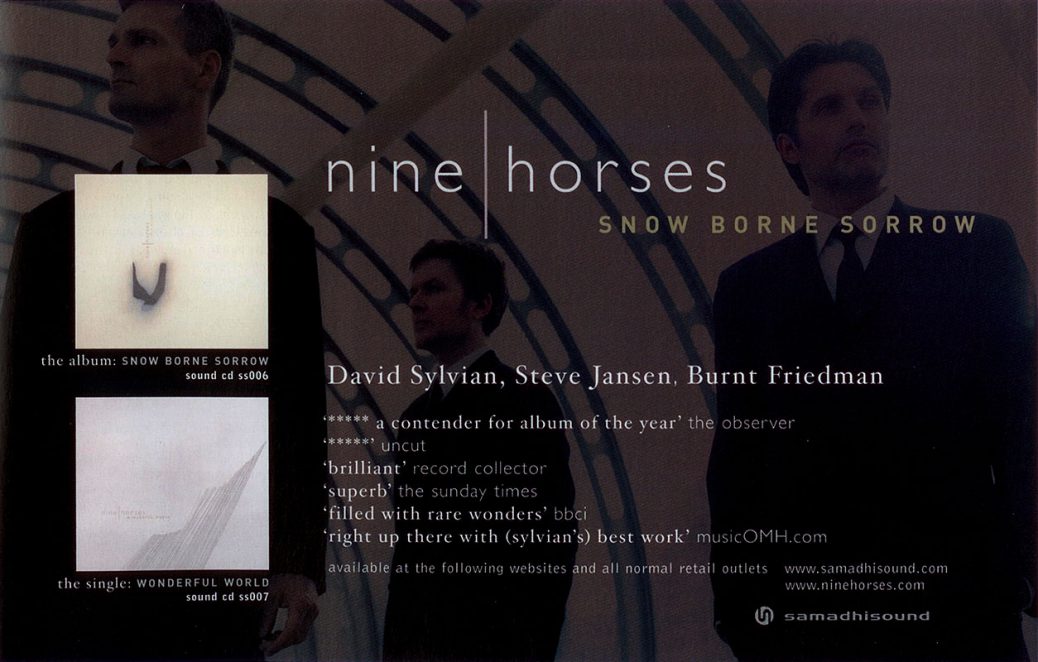

Like Japan, Rain Tree Crow and many of Sylvian’s solo ventures, it involves his percussionist brother Steve Jansen, with radical input from German electronic artist Burnt Friedman and various jazz and/or atmospherically inclined guests.

Not surprisingly, there’s not a hair salon hit-pick in earshot. Snow Borne Sorrow is an elegant but sombre album that includes some of the first songs Sylvian wrote in response to the September 11 disaster in his adopted home of America.

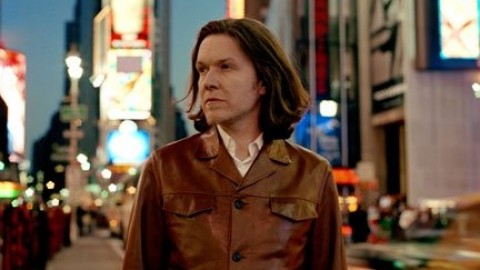

“You could say a lot of my work has becoming increasingly less commercial,” concedes the artist once voted the world’s most beautiful man in the British press.

“But it was all inherent in the first album I made (Brilliant Trees, a British hit in ’84). That was a blueprint for all that followed.

“When I broke the band up in ’82, I guess I wasn’t satisfied with the work I’d done. I was beginning to make some kind of breakthrough, recognising myself in my own work for the first time. I wanted to pursue that and not take into account any of the commercial elements that tend to compromise the work.

“I didn’t enjoy the game. It’s enormously time consuming to play the fame game and I just wasn’t interested. More than that, I valued my privacy. It was kind of about discovering my values for living, a philosophy. I started looking for spiritual depth and I feel like I planted fresh roots in some very potent soil.”

The spiritual dimension of Sylvian’s work intensified after a series of teachers led him to his guru, Mata Amritanandamayi (Amma), in ’95. His lush and exotic Dead Bees On A Cake album was dedicated to her four years later. Last year’s intensely bleak Blemish album was informed by his split with his wife, poet Ingrid Chavez, but owed no less to Amma.

“She informs my entire life in a very intuitive manner and therefore ultimately enables the work,” he says. With Blemish, if it wasn’t for the (spiritual) practice I had at the time, I wouldn’t have been able to delve that deep into such potentially harmful and negative emotions and resurface in a positive way.”

What’s remarkable is that Jansen, Sylvian’s younger brother and most frequent collaborator for 35 years, remains steadfastly opposed to this profoundly spiritual outlook.

“Steve and I have never seen eye to eye on a lot of issues, particularly involving philosophy, spirituality, belief systems,” he says.

“I’m not sure you could call him agnostic. Solipsistic, maybe? He has trouble acknowledging any kind of divinity in life. Anything out of the range of his own experience he refuses to acknowledge exists.

“It always used to make for quite a thorny relationship but over the years, you tend not to harp on the differences. The only time it reared its head this time was when we tried to name the project. In the end we went for a name chosen mainly for its absence of meaning. Nine Horses. But it works well enough.”