Every month, Wire magazine plays a musician a series of records which asked to identify and comment on – with no prior knowledge of what they’re about to hear.

Tested by Christoph Cox. Photos by Chris Buck.

During the period of the publication, Wire magazine offered an excerpt of an interview by Rob Young with David on their site. I’ve added it on this page.

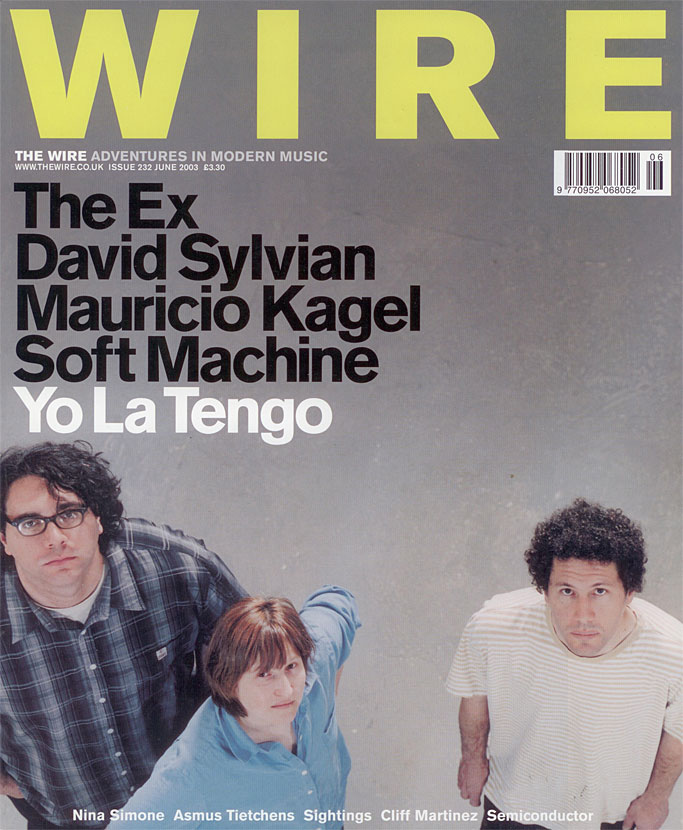

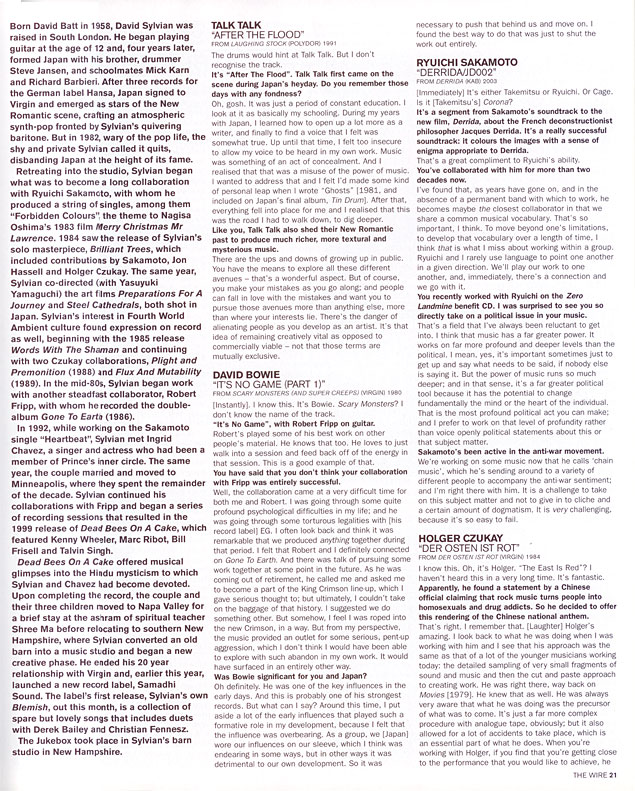

Born David Batt in 1958, David Sylvian was raised in South London. He began playing guitar at the age of 12 and, four years later, formed Japan with his brother, drummer Steve Jansen, and schoolmates Mick Karn and Richard Barbieri. After three records for the German label Hansa, Japan signed to Virgin and emerged as stars of the New Romantic scene, crafting an atmospheric synth-pop fronted by Sylvian’s quivering baritone. But in 1982, wary of the pop life, the shy and private Sylvian called it quits, disbanding Japan at the height of its fame.

Retreating into the studio, Sylvian began what was to become a long collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto, with whom he produced a string of singles, among them “Forbidden Colours”, the theme to Nagisa Oshima’s 1983 film Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence. 1984 saw the release of Sylvian’s solo masterpiece, Brilliant Trees, which included contributions by Sakamoto, Jon Hassell and Holger Czukay. The same year, Sylvian co-directed (with Yasuyuki Yamaguchi) the art films Preparations For A Journey and Steel Cathedrals, both shot in Japan. Sylvian’s interest in Fourth World Ambient culture found expression on record as well, beginning with the 1985 release Words With The Shaman and continuing with two Czukay collaborations, Plight and Premonition (1988) and Flux And Mutability (1989). In the mid-80s, Sylvian began work with another steadfast collaborator, Robert Fripp, with whom he recorded the doublealbum Gone To Earth (1986).

In 1992, while working on the Sakamoto single “Heartbeat”, Sylvian met Ingrid Chavez, a singer and actress who had been a member of Prince’s inner circle. The same year, the couple married and moved to Minneapolis, where they spent the remainder of the decade. Sylvian continued his collaborations with Fripp and began a series of recording sessions that resulted in the 1999 release of Dead Bees On A Cake, which featured Kenny Wheeler, Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell and Talvin Singh.

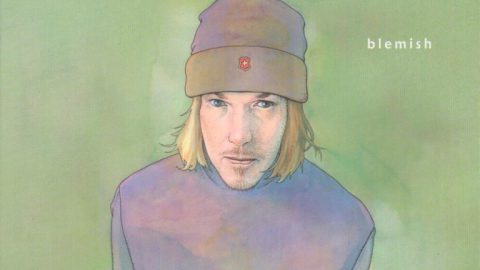

Dead Bees On A Cake offered musical glimpses into the Hindu mysticism to which Sylvian and Chavez had become devoted. Upon completing the record, the couple and their three children moved to Napa Valley for a brief stay at the ashram of spiritual teacher Shree Ma before relocating to southern New Hampshire, where Sylvian converted an old barn into a music studio and began a new creative phase. He ended his 20 year relationship with Virgin and, earlier this year, launched a new record label, Samadhi Sound. The label’s first release, Sylvian’s own Blemish, out this month, is a collection of spare but lovely songs that includes duets with Derek Bailey and Christian Fennesz.

The Jukebox took place in Sylvian’s barn studio in New Hampshire.

TALK TALK “AFTER THE FLOOD”

FROM LAUGHING STOCK (POLYDOR) 1991

The drums would hint at Talk Talk. But I don’t recognise the track.

It’s “After The Flood”. Talk Talk first came on the scene during Japan’s heyday. Do you remember those days with any fondness?

Oh, gosh. It was just a period of constant education. I look at it as basically my schooling. During my years with Japan, I learned how to open up a lot more as a writer, and finally to find a voice that I felt was somewhat true. Up until that time, I felt too insecure to allow my voice to be heard in my own work. Music was something of an act of concealment. And I realised that that was a misuse of the power of music. I wanted to address that and I felt I’d made some kind of personal leap when I wrote “Ghosts” [1981, and included on Japan’s final album, Tin Drum]. After that, everything fell into place for me and I realised that this was the road I had to walk down, to dig deeper.

Like you, Talk Talk also shed their New Romantic past to produce much richer, more textural and mysterious music.

There are the ups and downs of growing up in public. You have the means to explore all these different avenues – that’s a wonderful aspect. But of course, you make your mistakes as you go along; and people can fall in love with the mistakes and want you to pursue those avenues more than anything else, more than where your interests lie. There’s the danger of alienating people as you develop as an artist. It’s that idea of remaining creatively vital as opposed to commercially viable – not that those terms are mutually exclusive.

DAVID BOWIE “IT’S NO GAME (PART 1)”

FROM SCARY MONSTERS (AND SUPER CREEPS) (VIRGIN) 1980

[Instantly]. I know this. It’s Bowie. Scary Monsters? I don’t know the name of the track.

“It’s No Game”, with Robert Fripp on guitar.

Robert’s played some of his best work on other people’s material. He knows that too. He loves to just walk into a session and feed back off of the energy in that session. This is a good example of that.

You have said that you don’t think your collaboration with Fripp was entirely successful.

Well, the collaboration came at a very difficult time for both me and Robert. I was going through some quite profound psychological difficulties in my life; and he was going through some torturous legalities with [his record label] EG. I often look back and think it was remarkable that we produced anything together during that period. I felt that Robert and I definitely connected on Gone To Earth. And there was talk of pursuing some work together at some point in the future. As he was coming out of retirement, he called me and asked me to become a part of the King Crimson line-up, which I gave serious thought to; but ultimately, I couldn’t take on the baggage of that history. I suggested we do something other. But somehow, I feel I was roped into the new Crimson, in a way. But from my perspective, the music provided an outlet for some serious, pent-up aggression, which I don’t think I would have been able to explore with such abandon in my own work. It would have surfaced in an entirely other way.

Was Bowie significant for you and Japan?

Oh definitely. He was one of the key influences in the early days. And this is probably one of his strongest records. But what can I say? Around this time, I put aside a lot of the early influences that played such a formative role in my development, because I felt that the influence was overbearing. As a group, we [Japan] wore our influences on our sleeve, which I think was endearing in some ways, but in other ways it was detrimental to our own development. So it was necessary to push that behind us and move on. I found the best way to do that was just to shut the work out entirely.

RYUICHI SAKAMOTO “DERRIDAlJD002”

FROM DERRIDA (KAB) 2003

[Immediately] It’s either Takemitsu or Ryuichu Or Cage. Is it [Takemitsu’s] Corona?

It’s a segment from Sakamoto’s soundtrack to the new film, Derrida, about the French deconstructionist philosopher Jacques Derrida. It’s a really successful soundtrack: it colours the images with a sense of enigma appropriate to Derrida.

That’s a great compliment to Ryuichi’s ability.

You’ve collaborated with him for more thar decades now.

I’ve found that, as years have gone on, and in the absence of a permanent band with which to work, he becomes maybe the closest collaborator in that we share a common musical vocabulary. That’s so important, I think. To move beyond one’s limitations to develop that vocabulary over a length of time, I think that is what I miss about working within a group. Ryuichi and I rarely use language to point one another in a given direction. We’ll play our work to one another, and, immediately, there’s a connection and we go with it.

You recently worked with Ryuichi on the Zero Landmine benefit CD. I was surprised to see you so directly take on a political issue in your music.

That’s a field that I’ve always been reluctant to get into. I think that music has a far greater power. It works on far more profound and deeper levels than the political. I mean, yes, it’s important sometimes just to get up and say what needs to be said, if nobody else is saying it. But the power of music runs so much deeper; and in that sense, it’s a far greater political tool because it has the potential to change fundamentally the mind or the heart of the individual. That is the most profound political act you can make and I prefer to work on that level of profundity rather than voice openly political statements about this or that subject matter.

Sakamoto’s been active in the anti-war movement.

We’re working on some music now that he calls ‘chain music’, which he’s sending around to a variety of different people to accompany the anti-war sentiment; and I’m right there with him. It is a challenge to take on this subject matter and not to give in to cliche and a certain amount of dogmatism. It is very challenging because it’s so easy to fail.

HOLGER CZUKAY “DER OSTEN 1ST ROT”

FROM DER OSTEN 1ST ROT (VIRGIN) 1984

I know this. Oh, it’s Holger. “The East Is Red”? I haven’t heard this in a very long time. It’s fantastic.

Apparently, he found a statement by a Chinese official claiming that rock music turns people into homosexuals and drug addicts. So he decided to offer this rendering of the Chinese national anthem.

That’s right. I remember that. [Laughter] Holger’s amazing. I look back to what he was doing when I was working with him and I see that his approach was the same as that of a lot of the younger musicicians working today: the detailed sampling of very small fragments of sound and music and then the cut and paste approach to creating work. He was right there, way back on Movies [1979]. He knew that as well. He was always very aware that what he was doing was the precursor of what was to come. It’s just a far more complex procedure with analogue tape, obviously; but it also allowed for a lot of accidents to take place, which is an essential part of what he does. When you’re working with Holger, if you find that you’re getting close to the performance that you would like to achieve, he loses interest entirely. And those times when you felt you were really just grappling in the dark for something were the moments that really fascinated him. He caught them on tape. You weren’t even aware that you were being recorded.

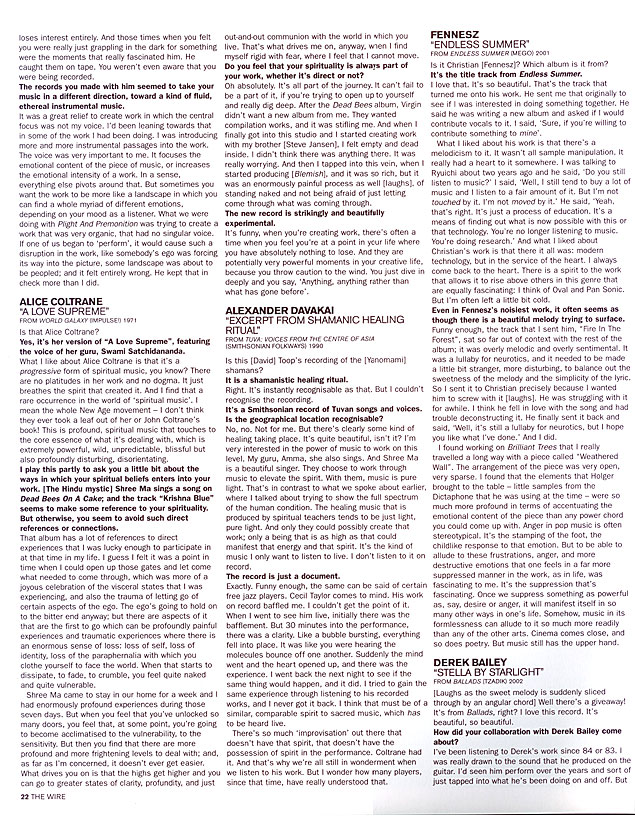

The records you made with him seemed to take your music in a different direction, toward a kind of fluid, ethereal instrumental music.

It was a great relief to create work in which the central focus was not my voice. I’d been leaning towards that in some of the work I had been doing. I was introducing more and more instrumental passages into the work. The voice was very important to me. It focuses the emotional content of the piece of music, or increases the emotional intensity of a work. In a sense, everything else pivots around that. But sometimes you want the work to be more like a landscape in which you can find a whole myriad of different emotions, depending on your mood as a listener. What we were doing with Plight And Premonition was trying to create a work that was very organic, that had no singular voice. If one of us began to ‘perform’, it would cause such a disruption in the work, like somebody’s ego was forcing its way into the picture, some landscape was about to be peopled; and it felt entirely wrong. He kept that in check more than I did.

ALICE COLTRANE “A LOVE SUPREME”

FROM WORLD GALAXY (IMPULSEI) 1971

Is that Alice Coltrane?

Yes, it’s her version of “A Love Supreme”, featuring the voice of her guru, Swami Satchidananda.

What I like about Alice Coltrane is that it’s a progressive form of spiritual music, you know? There are no platitudes in her work and no dogma. It just breathes the spirit that created it. And I find that a rare occurrence in the world of ‘spiritual music’. I mean the whole New Age movement – I don’t think they ever took a leaf out of her or John Coltrane’s book! This is profound, spiritual music that touches to the core essence of what it’s dealing with, which is extremely powerful, wild, unpredictable, blissful but also profoundly disturbing, disorientating.

I play this partly to ask you a little bit about the ways in which your spiritual beliefs enters into your work. [The Hindu mystic] Shree Ma sings a song on Dead Bees On A Cake; and the track “Krishna Blue” seems to make some reference to your spirituality. But otherwise, you seem to avoid such direct references or connections.

That album has a lot of references to direct experiences that I was lucky enough to participate in at that time in my life. I guess I felt it was a point in time when I could open up those gates and let come what needed to come through, which was more of a joyous celebration of the visceral states that I was experiencing, and also the trauma of letting go of certain aspects of the ego. The ego’s going to hold on to the bitter end anyway; but there are aspects of it that are the first to go which can be profoundly painful experiences and traumatic experiences where there is an enormous sense of loss: loss of self, loss of identity, loss of the paraphernalia with which you clothe yourself to face the world. When that starts to dissipate, to fade, to crumble, you feel quite naked and quite vulnerable.

Shree Ma came to stay in our home for a week and I had enormously profound experiences during those seven days. But when you feel that you’ve unlocked so many doors, you feel that, at some point, you’re going to become acclimatised to the vulnerability, to the sensitivity. But then you find that there are more profound and more frightening levels to deal with; and, as far as I’m concerned, it doesn’t ever get easier. What drives you on is that the highs get higher and you can go to greater states of clarity, profundity, and just

out-and-out communion with the world in which you live. That’s what drives me on, anyway, when I find myself rigid with fear, where I feel that I cannot move.

Do you feel that your spirituality is always part of your work, whether it’s direct or not?

Oh absolutely. It’s all part of the journey. It can’t fail to be a part of it, if you’re trying to open up to yourself and really dig deep. After the Dead Bees album, Virgin didn’t want a new album from me. They wanted compilation works, and it was stifling me. And when I finally got into this studio and I started creating work with my brother [Steve Jansen], I felt empty and dead inside. I didn’t think there was anything there. It was really worrying. And then I tapped into this vein, when I started producing [Blemish], and it was so rich, but it was an enormously painful process as well [laughs], of standing naked and not being afraid of just letting come through what was coming through.

The new record is strikingly and beautifully experimental.

It’s funny, when you’re creating work, there’s often a time when you feel you’re at a point in your life where you have absolutely nothing to lose. And they are potentially very powerful moments in your creative life, because you throw caution to the wind. You just dive in deeply and you say, ‘Anything, anything rather than what has gone before’.

ALEXANDER DAVAKAI “EXCERPT FROM SHAMANIC HEALING RITUAL”

FROM TUVA: VOICES FROM THE CENTRE OF ASIA (SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS) 1990

Is this [David] Toop’s recording of the [Yanomami] shamans?

It is a shamanistic healing ritual.

Right. It’s instantly recognisable as that. But I couldn’t recognise the recording.

It’s a Smithsonian record of Tuvan songs and voices. Is the geographical location recognisable?

No, no. Not for me. But there’s clearly some kind of healing taking place. It’s quite beautiful, isn’t it? I’m very interested in the power of music to work on this level. My guru, Amma, she also sings. And Shree Ma is a beautiful singer. They choose to work through music to elevate the spirit. With them, music is pure light. That’s in contrast to what we spoke about earlier, where I talked about trying to show the full spectrum of the human condition. The healing music that is produced by spiritual teachers tends to be just light, pure light. And only they could possibly create that work; only a being that is as high as that could manifest that energy and that spirit. It’s the kind of music I only want to listen to live. I don’t listen to it on record.

The record is just a document.

Exactly. Funny enough, the same can be said of certain free jazz players. Cecil Taylor comes to mind. His work on record baffled me. I couldn’t get the point of it. When I went to see him live, initially there was the bafflement. But 30 minutes into the performance, there was a clarity. Like a bubble bursting, everything fell into place. It was like you were hearing the molecules bounce off one another. Suddenly the mind went and the heart opened up, and there was the experience. I went back the next night to see if the same thing would happen, and it did. I tried to gain the same experience through listening to his recorded works, and I never got it back. I think that must be of a similar, comparable spirit to sacred music, which has to be heard live.

There’s so much ‘improvisation’ out there that doesn’t have that spirit, that doesn’t have the possession of spirit in the performance. Coltrane had it. And that’s why we’re all still in wonderment when we listen to his work. But I wonder how many players, since that time, have really understood that.

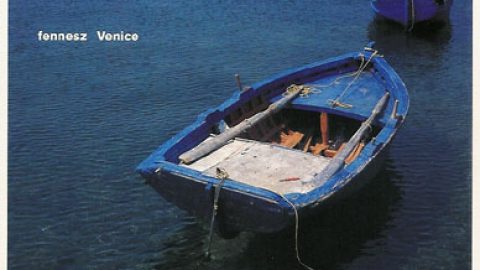

FENNESZ “ENDLESS SUMMER”

FROM ENDLESS SUMMER (MEGO) 2001

Is it Christian [Fennesz]? Which album is it from?

It’s the title track from Endless Summer.

I love that. It’s so beautiful. That’s the track that turned me onto his work. He sent me that originally to see if I was interested in doing something together. He said he was writing a new album and asked if I would contribute vocals to it. I said, ‘Sure, if you’re willing to contribute something to mine’.

What I liked about his work is that there’s a melodicism to it. It wasn’t all sample manipulation. lt really had a heart to it somewhere. I was talking to Ryuichi about two years ago and he said, ‘Do you still listen to music?’ I said, ‘Well, I still tend to buy a lot of music and I listen to a fair amount of it. But I’m not touched by it. I’m not moved by it.’ He said, ‘Yeah, that’s right. It’s just a process of education. It’s a means of finding out what is now possible with this or that technology. You’re no longer listening to music. You’re doing research.’ And what I liked about Christian’s work is that there it all was: modern technology, but in the service of the heart. I always come back to the heart. There is a spirit to the work that allows it to rise above others in this genre that are equally fascinating: I think of Oval and Pan Sonic. But I’m often left a little bit cold.

Even in Fennesz’s noisiest work, it often seems as though there is a beautiful melody trying to surface.

Funny enough, the track that I sent him, “Fire In The Forest”, sat so far out of context with the rest of the. album; it was overly melodic and overly sentimental. It was a lullaby for neurotics, and it needed to be made a little bit stranger, more disturbing, to balance out the sweetness of the melody and the simplicity of the lyric So I sent it to Christian precisely because I wanted him to screw with it [laughs]. He was struggling with it for awhile. I think he fell in love with the song and had trouble deconstructing it. He finally sent it back and said, ‘Well, it’s still a lullaby for neurotics, but I hope you like what I’ve done.’ And I did.

I found working on Brilliant Trees that I really travelled a long way with a piece called “Weathered Wall”. The arrangement of the piece was very open, very sparse. I found that the elements that Holger brought to the table – little samples from the Dictaphone that he was using at the time – were so much more profound in terms of accentuating the emotional content of the piece than any power chord you could come up with. Anger in pop music is often stereotypical. It’s the stamping of the foot, the childlike response to that emotion. But to be able to allude to these frustrations, anger, and more destructive emotions that one feels in a far more suppressed manner in the work, as in life, was fascinating to me. It’s the suppression that’s fascinating. Once we suppress something as powerful as, say, desire or anger, it will manifest itself in so many other ways in one’s life. Somehow, music in its formlessness can allude to it so much more readily than any of the other arts. Cinema comes close, and so does poetry. But music still has the upper hand.

DEREK BAILEY “STELLA BY STARLIGHT”

FROM BALLADS (TZADIK) 2002

[Laughs as the sweet melody is suddenly sliced through by an angular chord] Well there’s a giveaway! It’s from Ballads, right? I love this record. It’s beautiful, so beautiful.

How did your collaboration with Derek Bailey come about?

I’ve been listening to Derek’s work since 84 or 83. I was really drawn to the sound that he produced on the guitar. I’d seen him perform over the years and sort of just tapped into what he’s been doing on and off. But it wasn’t until I heard this album at this moment in my life that I felt, ‘There it is. There’s the opportunity that I was looking for back in 1990 with Keith [Tippett].’ I could finally see a way in.

Now, it’s still not improvisation in the pure sense. We’re not sitting in the room together performing. He recorded in London and sent the tapes to me here. I listened to the session one time and singled out a few pieces. And then, the second time I heard the pieces, I scribbled down lyrics and melody and then went for it on the third run-through. For me, that is improvisation. That’s as close as I can come to it – especially as a lyricist. I have trouble with the whole scat vocalist thing. Forget it!

It seems to me that his playing really shaped your vocal lines.

Absolutely. It determined everything, everywhere I went melodically and emotionally. I had a notebook of fragments. Once I had selected a track that I felt held certain possibilities for me as a vocalist, I’d respond with an opening line, intuitively, and then I’d run with that. Then I’d grab snippets from the notebook and respond to those fragments, and flesh out the lyric within the first or second listen to the piece, improvising the melody based on what I was hearing. There are wonderful switches in dynamics in Derek’s work, which isn’t always true of my work. It was just a matter of finding my way into the piece, in the emotional heart of the music.

BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON “JOHN THE REVELATOR”

FROM ANTHOLOGY OF AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC (SMITHSONIAN FOLKWAYS) 1930/1949

I have no idea.

It’s Blind Willie Johnson, from the Harry Smith anthology. Your work doesn’t generally have a bluesy feel, but a number of tracks on Dead Bees On A Cake reference the blues and other uniquely American musics.

It was mainly influenced by my wife, because that’s a genre of music that she loves. I was initially writing material for her own project, for her to sing. I was leaning toward R&B because I thought that would really appeal to her. But she failed to make a connection with the material. And when it came time for me to write my album, I was feeling a connection with it. It was tapping into the American musical culture, to some degree. But I am no purist. I don’t consider myself a musician that has ‘roots’ as such.

You’ve been living in America now for more than a decade. Has living here changed your relationship to American music?

I was never drawn by American culture per se. Quite the reverse, in fact. I could go back to the time of punk and Patti Smith and Television – that was when I was immersed in the culture somewhat. But I lost the thread of it after that and my interests went further and further afield. What I found is that, during the decade that I’ve been living in the States, you could potentially be just about anywhere in the world. The Internet changes everything in that respect. So, ‘What is your immediate culture?’ is the question now. I guess I embrace that fully. I don’t think I could survive on a staple diet of American culture I’m sorry to say [laughs]. There are beautiful elements to it, and musically there’s a lot going on. But a broader palette, a broader spectrum – you need that, I think.

My heart still belongs in Europe, and I find myself going back there more frequently now. And in the current political climate … I have a lot of friends that have left the country. There’s something happening here that is enormously dangerous and quite oppressive. Maybe it’s time to stand on that soapbox and put the word out, because there are becoming fewer and fewer options to speak out against what’s going on. And it has to be said.