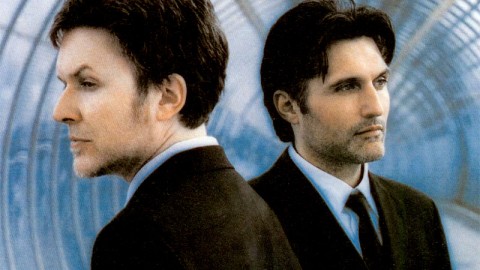

On the subject of Manafon. An exchange between David Sylvian and Marcus Boon.

Originally published on the now defunct manafon.com microsite to promote the release of Manafon.

“How much can you take away and still have a song?” This is the only note I have left on what was supposed to be a list of questions for David Sylvian. It reminds me of the beautiful moment in Leonard Cohen’s “Tower of Song” where “I said to Hank Williams/How lonely does it get/Hank Williams hasn’t answered me yet/but I hear him…” I didn’t ask David “how lonely does it get?”, but he answered me anyway, if you read between the lines, and carry on reading, or better still, listening… – Marcus Boon

MB: I just listened to Manafon. I wish I’d listened to it a week ago because I’ve been sort of at my wit’s end, and the first track on the disc in particular spoke to something I’ve been feeling rather intensely without being able to articulate it, or knowing anyone else who was able to do so. As with Blemish and some of your other recordings, I’m very thankful to have that experience of something obscure reflected back to me in a way that I am able to recognize.

DS: Can’t ask for more than that really.

MB: I’ve been thinking a lot about “deflation” recently, and the bubble not only in the financial markets, but in values, practices, activities, ideas in general. And the sense that all of these bubbles are bursting or deflating. I think it’s true in music, and the turn you took with Blemish is a rare thoughtful response to this problem… that melody, song, noise etc. themselves have become sites of a bubble that makes it almost impossible to listen to them, since all one hears is their “importance”, their value as capital, as gesture in a marketplace saturated with gestures. If Manafon reminds me of anything it’s Cage’s Indeterminacy, another beautiful meditation on the question of form…

DS: Oddly, the subject of “indeterminacy” has come up a lot lately both related to this and current work. I’m also familiar with the Cage work of that title and fascinated, as many composers over the years have been, by what can be done some place between overly determined composition and its opposite and how to bring the two closer together. Not exactly a new problem but relatively new to the area of songwriting, at least in this context. After all, all writing is an act of improvisation on some level. And the emphasis here is in the compositional process rather than the notion of repeat performance. That old chestnut of the fixity of the recorded performance…

MB: It’s very low-key, but moving too. If there’s a danger, it’s in your voice, where I can feel the temptation to sing “beautifully” (this being one of your gifts), and the further temptation to refuse that gift by speech-singing or extreme lack of affectation. It lends the disk a strange sense of drama though, since in the end so much depends on very small decisions about intonation. And in the end this is part of the music’s power, that sense of struggle at the level of your voice.

DS: Of course these decisions are core for most singers in any context but they do become magnified under such circumstances. Some might feel there’s an estrangement between singer and context which is part of the work’s attraction for me. In some instances there’d be little difference in taking a field recording of say, sounds in a cafeteria, isolating 6 minutes and approaching this as a workable context for vocal composition… and indeed, that’s how some of these ideas came together for me.

MB: I don’t imagine this was an easy disk to make, and the time right now makes it almost impossible to move forward, but you’ve found a way, and that’s really something.

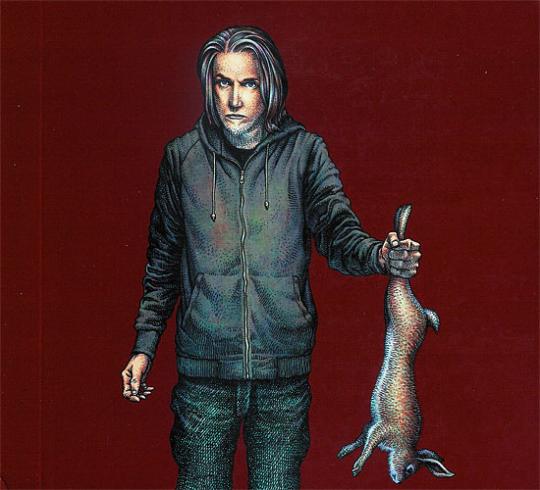

DS: In terms of responding to the material to hand it wasn’t a difficult album to make. The difficulties came in finding the raw material I was looking for. You don’t walk into a roomful of free improvisers and say “this is what I want you do to”. At least I didn’t. The skill is in choosing the right constellation of players for each set up and then gently nudging the session in the direction you feel might prove the more fruitful. With each session I had some vague parameters that helped me locate what it was I was after (and at the later sessions we had the benefit of listening to some of the earlier for guidance). In every session some amazing material surfaced but it wasn’t always of the kind that best served my interests or allowed room for the voice. Bit like hunting I guess… sitting patiently, waiting for the right species to show itself. Fascinating really.

MB: So how did you go about the hunting here? Are you writing the songs in response to the improvisations?

DS: I am as road tested on the Bailey tracks on Blemish. It comes down to making the right choices regarding who to work with in what constellation. If you get that combination right something is bound to come out of the sessions that’ll be close to anticipated… as far as that is possible. Gentle nudging, guidance, shifting of focus, pairing off performers, taking this one out of the picture, adding this… it’s a fascinating way of digging for a particular kind of gold.

The first sessions in Vienna lasted for eight days. I started with Polwechsel, Hautzinger and Fennesz, later came Noël Akchoté (didn’t make it onto the final album), then Keith Rowe joined us. Most of the material used came from the last two days with Keith, Christian, and Michael and Werner of Polwechsel. It took time for me to find what it was I was looking for but once the right combination was hit upon I knew I’d unearthed this, for want of a better term, modern chamber music I was after. Tokyo was a one day session. There was greater clarity and sense of purpose as a result of the time constraint but by that time I also had a clearer idea what it was I was after and how to find it. The only real specification made prior to the session was that Otomo use turntables with vinyl that featured chamber or modern string quartet music of some sort. The final session in London was also a one day affair. Again, I felt confident that I could find what I needed in that time frame with this incredible line up. I’d previously been given a session of improvised piano by John Tilbury which I’d managed to ‘track’ into the earlier sessions but this was the first time we worked together in person. Philipp Wachsmann was also a part of the London line up but again, didn’t make the final cut.

MB: But I still don’t understand how the recordings relate to the sessions, whether you’re using them as material and then dubbing vocals after editing and structuring in Pro-Tools… or are you literally improvising the song during the improv session and the recording is the same as the session? Or…?

DS: I take the sessions and work on them at a later time. I attempt to ‘improvise’ lyrics and melodies as I go, writing and recording all in a matter of hours. The basic tracks themselves undergo little or no editing as such. The structure pretty much remains as given from the original sessions. I might add an introduction or overdub other elements onto the original take. Here’s a couple of examples: “Senseless Violence”: Recorded in Vienna with Rowe/Polwechsel/Fennesz. I added guitar parts then layered Tilbury’s piano into the track then added the vocal and an introduction. “Greatest Living Englishman”: Initial take suggested acoustic guitar overdubs which I requested of Otomo and Tetuzi on the spot. I later cut and pasted some interesting turntable activity from an alternate take onto this track. I also added an introduction by cutting and pasting elements from an earlier take. Tilbury was added to the coda. Melody and vocal added. “Rabbit Skinner”: no editing. added acoustic guitar myself then vocals.

MB: Why the title “Manafon”? I google it and I get a Welsh village… I know “why?” is always a bad question…

DS: The question …why Manafon” leads me on a journey that reveals something of the nature of the entire project. This is a good thing for me because I had to back off from the work, spend some time away from it, as I’d begun to lose perspective. If someone had asked the seemingly simple question; “So, what’s this album about” I’m not sure I’d have had a ready answer.

If we start with the track “Manafon” we’re looking at a description of a man, a man of faith, who struggles with that faith, who imposes an order on the external world in the hope of finding it internally. A man who embraces the morals and values of his faith and lives by them but who also struggles with the silence that burns inside his own heart and mind. God’s silence. He’s a man out of time who begins to look, on the surface, more like some tragicomic figure as time passes. While he seems to be an insufferable individual in many ways* there’s a quixotic element in his quest for knowledge, for upholding morals and values that even he struggles with when it comes to believing in their efficacy.

Each verse is a description of minor aspects of the life of the poet R.S Thomas. The last two lines that end the piece are my own commentary. It spells out the sense of disillusionment and disorientation that the album starts with in “Small Metal Gods.” Therein lies one of the central themes behind the album. The title “Manafon” alludes to another. Manafon is indeed a village in Wales, a village in which Thomas lived for sometime and served as rector to the parish. In this small village Thomas had trouble filling the pews of a Sunday but in a sense it was something of an idyllic spot in which to raise a child (a strict, taciturn and somewhat indifferent parent), master his profession and write his poetry. So the physically real village became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination. A resource that’s called upon to unearth meaning, lend comprehension, provide motivation, a source of inspiration. It often plays a similar role in life for some as faith does for many. I came to feel that, in a sense, Thomas’ faith in, and need of, his outlet through poetry was more important than the faith that inspired it. They were uniquely, it seemed to me, bound to one another. Not as in the religious poetry of his and other faiths which generally speak of the ecstasy. He writes of the working poor and the landscape but it’s an austere world with little hope of comfort and so, by contrast, we are encouraged to concentrate on the fate of our souls etc.(yes, he wrote his own sermons too) But, alongside a kind of negation of many facets of his modern world (although, he was an odd mix of the recluse and the public figure even going so far as to lead CND marches and was very outspoken in favour of the bombing of English owed holiday homes in Wales), there’s also this underlying doubt and struggle with his belief, an uncertainty of the existence of the other (religious devotees are warned that this is a most dangerous period in their evolution, a time of suicides and renunciations).

I wasn’t sure I wanted to put a name, a source to the title track because my interpretation of Thomas’ life and work might be more a product of my own projections rather than detailing the facts of his life and work although, as I said, the particulars described in the piece are real enough. A man who exhorted Welsh poets to write in their own tongue when this was something he was unable to do (he did write an autobiography in welsh but it’s my understanding than his poetry was exclusively written in English as this was his mother tongue). He moved further and further west throughout his life until it was possible to move no further within the country he believed should be independent. But these facts are of only passing importance. As a source Thomas might only be of importance to me. The ambiguity of the lyric might work in its favour?

MB: Did you ever meet Thomas?

DS: No… I’m not sure I would’ve wished to at the time although I’d be very curious at this stage in life.

MB: Why does his story resonate for you now?

DS: I’ve read Thomas since the 1980’s. There was something about his austere vision of the world which, as I said, belonged to another time. He was of the generation that lived through world wars I and II, that rejected the easy comforts of modern life, that in a sense wanted more to be asked of them by society and in turn wanted society to rise out of its weak minded ambivalence and desires for basic pleasures and aim for higher goals, a more noble sense of itself and its destiny. Thomas seemed in search of a deeper, more profound connection with the natural and spiritual world whilst appearing to battle against inner demons which show familiar signs of being born of repression. Very British in that respect.

What interests me is how individuals, in pursuit of “truth”, to fulfill a life’s promise by living it with a sense of dignity and purpose, can find themselves derailed, disillusioned. I’m not saying that’s what happened to Thomas but I can’t help feel that his wasn’t a happy existence or that the life he chose to live bore significant fruit or at least that which didn’t have a slightly bitter aftertaste. He appears to have been profoundly single minded, inflexible, proud, disparaging. All qualities we think of today as standing in the way of our development. But there’s still a part of me that applauds the effort, the adherence to a path, a devotion to a life’s cause. For all its apparent bitterness and tragicomic contradictions there’s something beautiful about the man’s dogged devotion to writing, to poetry. Like the character in Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice who everyday waters the dead tree in the belief that one day it’ll return to life. This is the work of faith isn’t it? Thomas’ path was complicated by the seeming expression of doubt in God’s existence although when asked the answer was a matter of fact ‘of course I believe in God’.

Who or what we chose to believe in or deny is very telling isn’t it? Maybe I’m attracted to the stories of individuals who search for meaning on their own terms. I’m increasingly wary of hierarchies and societal norms and traditions… of “givens”. But what I’m fascinated by is the devotion to a creative discipline. The meaning with which the work imbues the life regardless of its reception and, to a certain extent, its importance.

MB: Manafon is a dark record, and the music often evokes a feeling of fear, a kind of creepy post 9/11 feeling, unsettled in a very quiet way – but the singing is a counterpoint to this, facing it, telling a story that passes through the zone of fear, responds to it…

DS: There are many subtle and not so subtle references to the creative imagination throughout the album. Allusions, quotations etc. Each piece seems to deal with the twin subject matter of inspiration/imagination and disillusionment in its own way. “Random Acts…” looks at what it means to be disillusioned with the ways and means with which societal values are protected and defended and a possible scenario to come as the tightening strictures of law and order become too unreasonably repressive and spontaneous acts of terrorism, not based in ideology but in anger and frustration and the desire for a liberation from the overbearing guidelines of the state, erupt. Minor acts of destruction as a creative act. This is something that seems inevitable as reasoned argument, protest, and related acts become increasingly inhibited under law.

MB: You’ve been one of the few singers, especially with “World Citizen”, but also some of the tracks here, who’s responded directly to the political situation in America and Europe after 9/11. I know a lot of people who think of you as a singer of “spiritual” or maybe existential songs about inner struggle are surprised at this. Where did the directness of your response to what’s been going on come from???

DS: Actually, I think there may’ve been more responses to 9/11 and the post 9/11 environment than it may appear.

Working with Ryuichi on a couple of projects that he instigated pushed me into writing overtly political pieces but I never felt very comfortable with this approach. The soap box numbers which resulted leave little room for individual interpretation. It was interesting to touch upon that style of writing, a somewhat prosaic approach to lyric writing and if you’re going to write an openly political piece for a specific cause there’s no point in being the least bit indirect in your approach. But I tend to think of it as the antithesis of the kind of material that I’m personally interested in and a perversion of the innate power of music which has a potentially political element to it at all times, as to affect or stimulate change in one individual is a political act as far as I’m concerned. Having walked down that road on a couple of projects with Ryuichi I began writing material that appeared more grounded in current events or making references to contemporary events but in the context of narrative, as reference, as possible catalyst. This was because there was no remit, I was free to deal with the subject matter as I chose. The first piece that I felt happy with in this respect was “Atom and Cell”. It was written some time before “World Citizen (I Won’t be Disappointed)”, which is a piece I’m also happy with, but released at a later date. “Wonderful World” also deals with similar subject matter.

Living in the United States has also made me more politically aware because I feel there’s so much work to be done here in terms of equality, liberty, the raising of awareness on numerous issues, the fight against the oppressive nature of the Christian right and the power of multinational corporations, the lobbyists etc. The US, for all its eccentricity, is powerfully conservative. I guess I tend to find that conservatism somewhat oppressive and so certain issues have begun appearing in the work which mightn’t be there otherwise. Also, I have serious doubts that there’s such a thing as a free press in the US. More often than not the media seems to act as mouthpiece to the politicians mainly for fear of losing access to them. The politicians certainly aren’t thoroughly examined by the media by any stretch of the imagination. Scrutiny of the Bush administration pre and post war was almost wholly absent. All voices of dissent were suppressed or eradicated which made it all the more important to add one’s voice in the hope of something, anything, breaking through.

MB: It’s striking how English things sound on Manafon. Not just the lyrical concerns, but even your own intonation and the choice of phrases…

DS: There was a desire to create a work that had a definitively British or, possibly more specifically, English quality about it. Even with many nationalities involved in its making that’s something I hope I’ve managed to maintain in the finished work. Why take that route? Most of the decisions made in this respect are initially of an intuitive nature. An intuitive understanding of the nature of the work which presents itself during the gestation period between prior to conception and realisation. It’s a map against which every step taken on the road to realisation is measured and quantified. It helps when making very elementary decisions about the nature of the work such as the instrumentation (what is or isn’t excluded e. g. no percussion) as well as the over all tone, feel, and real content of the compositions. ‘Blemish’ also wore its Englishness on its sleeve (think of pieces such as ‘the only daughter’ with lines such as ‘do us a favour, your one and only warning, please be gone by morning), in that sense and many others “Manafon” is a companion piece. Maybe this “Britishness” is a product of trying to speak with a true voice? To give voice to something that exists within me as memory, lived experience, or knowledge. To place its roots in specific soil… and I’m not speaking of musical roots which is something I’ve always fought against in a way, but in a specificity bought about through circumstances of birth, in my case, London from the late 1950’s (write of what you know). To find voices to give voice to that experience. I found it easier to write in the third person in that respect. Project my own concerns onto these characters. I guess it’s a bit like living in the States and reflecting on that British character once removed. Distance helps. It allows you to speak some home truths via slight of hand. But there’s absolutely no nostalgia in this examination of character. It’s a self examination and by extension an examination of certain aspects of the British character and human nature in general although, I have to say, I’m not really an ‘everyman’ in that respect and maybe that’s one reason why my work’s failed to find a bigger audience. Hard for me to tell. I only know what it’s like to have lived inside my own skin.

MB: To me something that resonates in the record is an odd sense of disillusionment with spiritual paths. I’m not sure whether disillusion is the right sense for it, but just skepticism about the community, the motives, the shiny images of deities that I know were made in a sweat-shop in Mumbai… to the point where I wonder what’s left aside from something transcendental, that I have very strong feelings for and a deep attraction to, but which I’ve now subtracted all human links to, because I can’t believe in the links any more. In a way, the “path” becomes truly open, but often I don’t see any path at all. So maybe the whole universe becomes “improv” at that point?

DS: This is an interesting development though isn’t it? I’ve read, as I’m sure you have, that some teachers have recommended a thorough detox in professional analysis before ever approaching a path or discipline. I’m not sure that’s a cure all but it’s pretty difficult for us to see past our own deficiencies, our neuroses, and so see what clearly motivates us in our search. No doubt there something primal in us that sets us on one journey or another but that’s coloured or tempered by all manner of other needs and desires and it’s here that we possibly come undone, use a distorting lens to enable us to see what it is we wish to see?

It does become increasingly difficult to believe in the testimony of others… the links and lineage… there’s so much self delusion, politics, power grabbing and maintenance etc. Once you’ve been through the wringer a few times, more than a few times, you begin to only believe in the voice inside yourself which rings true*. Personal experience before you’ve time to (re)interpret it… epiphanies, unanticipated, sustaining.

I find the whole process fraught with difficulty but fascinating. Letting go of ambition seems to be part of the process too. Ambition for personal progress. Yes, improv or winging it. I like the state of hopelessness. Hope really does tend to get in the way. It takes you out of the present towards an ideal. To live without hope but without a loss of love for life… that’s a great starting place it seems to me.

*I don’t believe in magic,

I don’t believe in I-ching,

I don’t believe in bible,

I don’t believe in tarot,

I don’t believe in Hitler,

I don’t believe in Jesus,

I don’t believe in Kennedy,

I don’t believe in Buddha,

I don’t believe in mantra,

I don’t believe in Gita,

I don’t believe in yoga,

I don’t believe in kings,

I don’t believe in Elvis,

I don’t believe in Zimmerman,

I don’t believe in Beatles,

I just believe in me,

Yoko and me,

And that’s reality.

God. John Lennon

(or alternately… delusion… all of it… and there’s relief in that).

And there is no maker

just inexhaustible indifference

and there’s comfort in that

so you feel unafraid

Snow White in Appalachia. David Sylvian