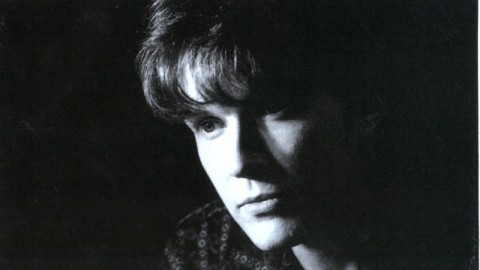

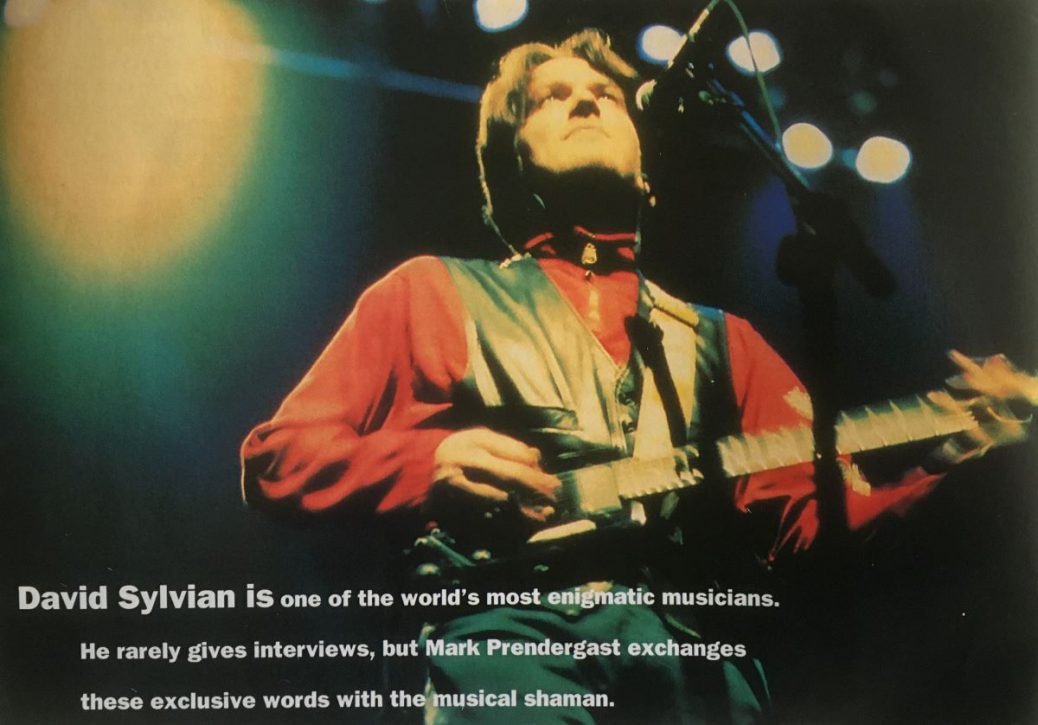

David Sylvian is one of the world’s most enigmatic musicians. He rarely gives interviews, but Mark Prendergast exchanges these exclusive words with the musical shaman.

THE SYLVIAN STORY

DAVID SYLVIAN HAS ALWAYS had the ability to mix genres and, at every stage of his career, come up with something startlingly different. During the heady Japan days, his thoughts were on avant-garde music within a pop form. For the 1981 Tin Drum album, Sylvian taught himself the rudiments of classical Japanese music, and, for the haunting Ghosts, he developed a style of using ‘abstract synthesizer lines’. Interested in Stockhausen as well as modem Japanese composers such as Toru Takemitsu, he spent much time during the 1980s in Tokyo studios developing a sound which was both flexible and open.

His main helpers were Ryuichi Sakamoto and Seigen Ono. After the success of Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence in 1983, he shifted gear. In his own London studio he sketched out songs on a 4-track tape recorder and added basic percussion, synth and guitar tracks. Travelling to Berlin he brought such musical explorers as trumpeter Jon Hassell and electronic musician Holger Czukay for the definitive Brilliant Trees, which also featured Sakamoto and bassist Danny Thompson. His emphasis was on creating a sense of space, and this led neatly to a phase of ambient musical output.

Seemingly inspired by Eno, Sylvian then recorded the instrumental works Preparations For A Journey and Steel Cathedrals in 1984, the latter being his first piece of work with Robert Fripp.

For 1986’s double album Gone To Earth, Sylvian was abetted by guitarists Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson. It was recorded at the Town House and the Manor, and produced by Steve Nye, with whom Sylvian had frequent brainstorming sessions. Sylvian was explicit about the recording “showing an appreciation of life and nature.”

Sylvian had different musicians record in strange places in order to create a looser feel for his next album, 1987’s Secrets of The Beehive. Recorded in France, Holland and Bath, it featured Danny Thompson, David Torn and the string and brass arrangements of Ryuichi Sakamoto.

If people thought that Sylvian had found a cosy formula then his next venture with Holger Czukay was a shock. The results of a night in an old cinema with pianos, guitars, vibraphones, synths and various radio samples was Plight & Premoniton (1988) — one of the first modem ambient albums, replete with spiraling tones punctuated by radio and morse-code interference. It opened Sylvian up to the possibilities inherent in tape and free improvisation. He returned to Cologne after a world tour to make another record, Flux & Mutability, with most of Can and the flugelhorn-player Markus Stockhausen, son of Karlheinz.

To prove that he never was the woolly aesthete portrayed in the press, in 1989 Sylvian released a single, Pop Song. It was possibly his most commercial offering since Red Guitar, despite his claim that he “was experimenting with tonalities, tunings and quarter tones in the programming of synthesizers.” This wish to continually experiment was also seen in the reformation of Japan as Rain Tree Crow in 1990. It was the first time the band had taken improvisation principles so far, a move at least partially influenced by Sylvian’s previous work with Holger Czukay.

More collaboration

Having been through a very positive relationship with Japanese artist and designer Yuka Fujii, Sylvian then went through a period of emotional upheaval in the early 1990s. During this time he took on collaborative work, partly as a means to help him come to terms with the emotional side of his life. He has now moved to Minneapolis and married Prince protegée Ingrid Chavez, and The First Day, recorded with Robert Fripp, has a marked optimistic feel. It saw Sylvian come as close as he’s ever done to hard rock. When it came to recording at Dreamland in Woodstock, Sylvian decided to drop the ballads and “concentrate on the heavier numbers.”

All vocals and guitar parts were recorded at Kingsway in New Orleans, and the mixing was carried out at Electric Ladyland in New York with the help of Peter Gabriel’s engineer David Bottrill. The First Day uses distorted vocals and looping devices, courtesy of Bottrill, to convey a sense of ferocity. It is a mixture of the crafted studio layering favoured by Sylvian and the more direct technique which is Fripp’s métier. It ends with the sublime ambient piece Bringing Down The Light, and Sylvian describes it in terms of a journey.

“Throughout the album there is a kind of sense of frustration, anger and mental chaos, as well as world chaos, which is finally resolved in some sense of optimism, some sense of new light.”

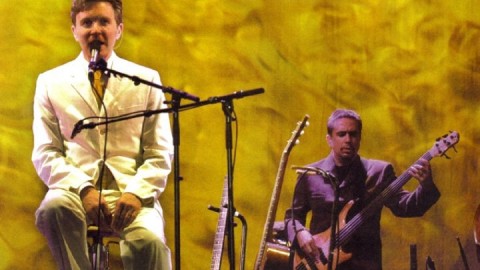

Damage, the new live Sylvian/Fripp album, works as both a career statement and a public expression of peace. Here is an artist finally enjoying his own music. The album contains two ballads, Damage and The First Day, from the previous session that reveal something of what the artist is talking about above. But there’s also some fine material from Gone To Earth and Rain Tree Crow. It is the result of the Sylvian/Fripp tour of Japan, Europe and North America in 1993 and 1994

“We were pretty well problem-free. It was a great experience as a result. I have wonderful memories of touring with my wife and 3-week old baby at my side and standing back in the shadows of the stage watching Robert let loose on his guitar on those special nights when the energy was that much more intense and the angels shared the boards with us.”

With so many collaborations behind him, it’s not surprising that Sylvian’s current working method is as varied as ever.

No Damage limitation

“I don’t work with any one particular synth — I have a variety. I do use them in conjunction with outboard effects, which includes the Eventide 3000. The ‘fine tuning’ involves a variety of treatments which go to enhance the sounds programmed into the synth modules – signal deterioration or distortion, harmonic enhancement, delays, modulation, equalisation and so on. My keyboard work on Rain Tree Crow comes to mind, especially my treatment of Mick Karn’s saxophone on Every Colour You Are.”

Over the years, David has pretty much been there and seen that as far as studio technology goes. Nowadays, his set-up leans very much towards digital technology, as he explains: “Ingrid and I have just completed the basics of our home studio with assistance from our engineer Dave Kent. Equipment includes an automated 24-track Amek Einstein super ‘E’, three Alesis ADATs (soon to be replaced), a selection of outboard gear including the aforementioned Eventide, a TC 2290, an Ensoniq DP/4 and synth modules. I work with Vision software on a Mac.”

Last month in FM, Robert Fripp talked about Sylvian’s sound-sculpting methods. David is keen to expand on this process: “Sculpting sound is something that most synthesists are involved with in one way or another. Most recently I’ve been working with samples from a variety of sources and manipulating them in the computer, creating soundscapes of a more dramatic nature. I worked closely with Robert on the large variety of guitar sounds produced for The First Day, removing excessive effects wherever necessary, adding occasional treatments, generally trying to create an overall sound that had both clarity and density.”

And these days David is not limiting himself to any one type of instrument. “Outside the voice, guitar and piano/keyboards, I blast away on trumpet sometimes to keep the diaphragm, lungs and throat exercised… but that’s a long way from playing the thing well.”

But looking back, it’s the technology that has been the backbone of most of Sylvian’s output and defined his sound. “Well, first I’m not entirely sure whether I have a ‘sound’ as such. If I do, then I believe that it’s created mainly by the writing and the voice. However, I do consider the Prophet 5 to have been of great importance to me in my development as a synthesist and player. The increasing accessibility of much home-recording equipment has, and continues to have, a wonderfully creative and liberating influence. And then there’s the developing technology of samplers and the countless possibilities they introduce.”

So what of the future? Having tried pop, ambient, electronic, pure vocal, ballad and hard rock, what’s next for Sylvian?

“Changes in the ‘style’ of music come as a result of what desires to be given expression and is not an end in itself, so I’m unable to second guess where I’ll be led in the future.”