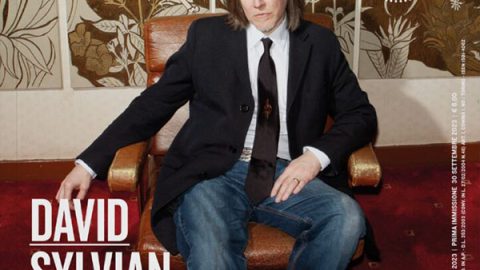

Originally published by Sound On Sound at June 17th 1994.

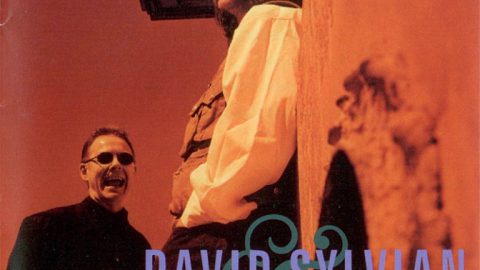

Despite having spent more than 15 years in the public eye, David Sylvian remains an enigmatic figure who has reinvented his own musical style constantly, both within his solo work and in his collaborations with musicians as diverse as Holger Czukay and Robert Fripp. PAUL TINGEN charts the history of the thinking musician’s thinking musician.

“Improvisations are particularly important in collaborative work, because what’s important there is the relationship between the musicians involved. It means that you’re not bringing your own limitations in terms of structure and songwriting into the studio with you.””When I’m writing songs, I very rarely write in a detailed way about the state of my own mind. Instead I try to generalise my experiences. I don’t want people who’re listening to my music to think: ‘oh, that must be what he’s going through.’ I prefer that they’re relating to my work because it touches something in themselves. I do use my own experiences as base material, but try to transform them into some kind of archetypal experience that’s also significant to other people.”

Deep and meaningful words. But then, David Sylvian has always been the thinking musician’s thinking musician. He has refused to surrender to the lowest common denominator of rock ‘n roll, the attitude that at heart the form cannot be much more than a bit of fun for the youth of today. At 36, Kent-born Sylvian is one of the younger veterans of the international music scene. In many ways his career has been a battle with the conventions and prejudices of rock ‘n roll. As a 20-year old aspiring pop star he tried to manipulate them for his own ends, appearing in the limelight with Japan, sporting platinum-blonded hair and an effeminate image inspired by the glam-rock of the New York Dolls and David Bowie. Musically, Japan were lightweight when they released their debut album, Adolescent Sex, in 1978. Like many artists who emerged in the late ’70s, Sylvian and Japan were learning how to make music as they went along, becoming more musically interesting with the release of their third album Quiet Life (1979), and reaching a peak with their magnum opus and commercial breakthrough Tin Drum (1981). Tin Drum was revolutionary and highly influential, featuring innovative ways of structuring a rhythm section as well as many synth textures unheard at the time. To everyone’s astonishment, Sylvian left the band soon after Tin Drum to pursue a solo career. On the phone from Minneapolis, where he now lives, Sylvian comments: “I’m still proud of the arrangements and sounds, of the production approach of Tin Drum, but I wasn’t sure that there was anything of substance. It’s not that the songs didn’t stand up. As pop songs there was nothing wrong with the structures and compositions. It’s more that my values changed in terms of what the function of music should be and what songs should convey.”

CATHARTIC

Though they had graduated from the naive to the innovative in less than four years, Japan remained first and foremost a pop band, and the creative constraints had clearly become too much for Sylvian. Yet he also acknowledges his time with the band as an important formative period. “I avoid looking back at the first two Japan albums. They were enormous mistakes that grew out of extraordinary circumstances. We were all young and surrounded by older people who thought they knew best. But they were important mistakes. I don’t think I would have learnt half as much had they not been so obvious. On Quiet Life and Gentlemen Take Polariods (1980) things started to change. We were getting into synths and were producing some interesting sounds and atmospheric pieces. Tin Drum was a wonderful challenge to work on. Richard (Barbieri) and I were stretching ourselves enormously in terms of programming new sounds. We only used a Prophet 5 and an OBX and tried to emulate fictitious musical instruments. It was really hard work. But it was worth it.” According to legend, recording Tin Drum brought producer and engineer Steve Nye to the verge of a nervous breakdown, as Sylvian and keyboardist Barbieri simultaneously programmed the synth sounds for the album in the recording studio, day after day.

Sylvian’s solo career began with the brilliant Brilliant Trees (1984), which was soon followed by Gone To Earth (1986) and Secrets of the Beehive (1987), as well as the limited-edition instrumental cassette Steel Cathedrals (1985). During the ’80s, Sylvian also released two collaborative instrumental albums with Holger Czukay — Plight & Premonition (1988) and Flux & Mutability (1989) — and collaborated with Ryuichi Sakamoto on classic tracks like Bamboo Houses (1982) and Forbidden Colours (1983, part of the soundtrack of the film Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence. Ever trying to expand his creative horizons, Sylvian also developed an interest in visual and audio-visual material, publishing a book of polaroid collages called Perspectives (1984), producing a video called Steel Cathedrals (the cassette was the soundtrack) and writing the score for a contemporary dance performance, called Kin, that played in London in 1987. However, the centrepiece of his artistic work was his solo albums; he comments that it was on Brilliant Trees that he first managed to express what he was missing with Japan: “From Brilliant Trees onwards I have a clear relationship with my work. All my solo albums have grown from values that I still live by; my aim is to create music that has healing or cathartic properties for a lot of people. I try to take people on a journey. The track ‘Let The Happiness In’ from Secrets Of The Beehive is a graphic example of that, where everything starts very low-key yet ends up with a sense of hope. As a listener I prefer to be taken through the stages of doubt, before being shown the way out. I find it difficult to bang a drum of positivity and go: ‘everything is OK, it’s all going to work out fine.'”

In terms of acceptance, Sylvian has had a remarkably easy ride. He quickly established himself as a widely respected artist, especially influential with musicians — his ongoing experimentations with sonic textures, whether in synth patches or sound treatments, have greatly contributed to this. But from the mid-’80s onwards, his music gradually became more introverted and melancholic and, as he became increasingly attracted to improvisation, his music became more abstract or — as some would say — formless. His audience was still accepting him, but were they understanding him?

CHANGE

Sylvian’s 1988 live tour, In Praise of Shamans, with guitarist David Torn, trumpet player Mark Isham, and brother and former Japan drummer Steve Jansen, appeared to confirm fears that he was drifting into a no-man’s land of despondency. There were many long and, at times, rather directionless improvisations, a world away from the tight and economical arrangements he’d always favoured. And his unusual synth textures, which in the past had sounded exotic and fresh, often came across as dreary and unfocused in the new context, adding to the overall feel of gloom and doom. Sylvian himself looked shy and withdrawn and distinctly uncomfortable. It wasn’t altogether surprising that his output decreased in the years to come — indeed, it wasn’t until early 1991 that new material was released. Rain Tree Crow was a reunion project involving the other three former Japan members, Barbieri, Jansen and bassist Mick Karn. At the time Sylvian explained that he wanted to experiment in a band format with the improvisational approach that he had developed with Holger Czukay, and assess where he and the former Japan band members had arrived in their musical development. Sylvian: “I’m very proud of that record. Despite personal problems between the members during the mixing stage, I think we managed to produce a good record. There are some wonderful performances on it and I think that it didn’t sound at all like the Japan of old, which is what I had hoped for.”

In 1990 and 1991, Sylvian rekindled his interest in audio-visual work with a collaboration with artist Russell Mills which produced a large-scale installation called Ember Glance, consisting of light projections, photography, sculpture and music by Sylvian. It was executed live in Tokyo in 1990, and crystallised in a book and CD published in late 1991. The end of 1991 marked a turning point in Sylvian’s personal life. He confirms that the years previously had indeed been “very dark and very heavy” for him and that it took him “a long time to come through.” As so often in life, change announced itself on several levels simultaneously, and a major event was his meeting with former Prince protegee Ingrid Chavez. Sylvian and Chavez married in February 1992, two and a half months after meeting, and he soon moved to Minneapolis, where she was living. Late last year Chavez gave birth to their first child.

TURNING POINT

The dramatic changes in Sylvian’s personal life reflected quickly in his artistic output. First there was another collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto. Then, in the spring of 1993, came The First Day, a collaboration with Robert Fripp which took his fans and the press aback — this was definitely not the Sylvian of old. The album was unusally aggressive and hard-hitting, featuring the wild, distorted and full-frontal antics of Robert Fripp on electric guitar, funky and gutsy rhythms courtesy of drummer Jerry Marotta and stick player Trey Gunn, and seriously direct and sometimes disturbing lyrics by Sylvian. He comments: “Making this album was definitely a cathartic experience, both for Robert and myself. It comes out of traumatic experiences, but it also resolves them. In the end healing takes place. In working on this album I really surfaced from the experiences of the previous years and managed to move on. It was a turning point for both of us.” The two men had worked together before on Sylvian’s second solo album, Gone To Earth, in 1986 and plans they had made at the time for a further collaboration only started to come to fruition when Sylvian was asked to do a tour of Japan in 1992. Sylvian: “Robert approached me in late 1991 about whether I wanted to join a new King Crimson he was forming. Though very flattered, I decided that I didn’t feel equipped to take on the whole baggage and history that comes with being a member of King Crimson. So instead we took the offer of the tour as an opportunity to write material for an album.”

The First Day was recorded between December 1992 and March 1993 at studios in New York and New Orleans, with help from Jerry Marotta on drums, and with David Bottrill behind the mixing desk. The latter two had both worked extensively with Peter Gabriel; Sylvian explains that he chose Bottrill to get away from the dry, silken sound of his long-standing recording partner Steve Nye, and achieve a more up-front rocky sound. “I had a desire to go into another sonic area. I love the warmth and beauty of the tones that Steve gets. Steve also used to give me a lot of feedback on the way I arranged things. But as I have continued to develop, it just seemed natural to move away. We’d exhausted our relationship to some degree. We might work together again, but for now I enjoy working with different engineers and co-producers.”

As a result, Sylvian went into the studio with a new engineer, pre-improvised material, a new outlook on life and a new musical partner. It’s not surprising that the results turned out unlike anything he’d done before. He remembers: “In the end, three pieces were directly culled from live-performances, ‘Jean The Birdman’, ‘Firepower’ and ’20th Century Dreaming’, although the latter two were greatly extended and transformed in the studio. Once we had recorded these three pieces, we faced the choice of adding some ballads or making a more dynamic album. We decided that the album should be more confrontational, so we put the quieter pieces aside for the time being, and will maybe record them on a second joint album.”

An interesting aspect of The First Day is that it combines the two previously rather disparate approaches to making music that Sylvian favoured — the tightly arranged and the loosely improvised. For Sylvian, this was a step forward: “Improvisations are particularly important in collaborative work, because what’s important there is the relationship between the musicians involved. Improvisation allows that to come into focus, how you react to each other in the spur of the moment. I enjoyed working in that way with Holger Czukay and Rain Tree Crow. It means that you’re not bringing your own limitations in terms of structure and songwriting into the studio with you.

“On the other hand, what feels good whilst you improvise isn’t always going to be interesting for other people to listen to. So we spent a lot of time working on pieces and developing them. It was a challenge to make them work for other people. Neither of us had thought of putting on a piece like ‘Darshan’, which is 18 minutes of rhythmically repetitive music with jazz-type improvisations going on throughout. So there was a lot of re-structuring going on in that piece, whilst at the same time I tried not to weaken the live performance that gave it its power in the first place. It was a way of combining Robert’s and my approach to recording music, and a challenge that I enjoyed.”

Last December, Sylvian had a triumphant return to the London stage when he played two concerts with Fripp at the Royal Albert Hall, no less. The concert was a world away from the dark introversion of his 1988 concerts. Though never an entertainer, Sylvian (whose gear for the occasion included a Steinberger guitar, Yamaha KX88 MIDI controller, Roland JD990, Korg Wavestation A/D, M1R, Zoom 9030, Akai S1100 and Kurzweil 1200Pro1) looked relaxed and in his element. Musically the concert was close to a revelation. The First Day was an interesting album, but somehow marred by a certain ‘monochrome’ mood and sound, as well as crudeness of some of the material. It may have fulfilled a cathartic function for Fripp and Sylvian and contained some excellent music, but it didn’t quite make an altogether satisfying listening exerience for me. At the Royal Albert Hall though, Fripp, Sylvian and Gunn, with help from drummer Pat Mastelotto and eminent guitarist Michael Brook, put down one of the best live shows of 1993. What hadn’t always worked on the album suddenly came to life and caught fire. And some elegant and deeply moving ballads by Sylvian proved enough counterpoint for the heavier pieces. A live album with material taken from the last world tour has been mixed by Bottrill and Fripp, and will be released this summer. Meanwhile, Sylvian is working with Chavez on her forthcoming solo album, and a long-awaited fourth solo album appears to be on the cards too.

RICHARD BARBIERI: PROGRAMMING TIN DRUM

Richard Barbieri and David Sylvian were together responsible for the unsual synth textures that turned Tin Drum into such a musical milestone. The highly original, organic and off-beat sounds were often reminiscent of unknown, exotic instruments. Despite the incredibly rich variety of synth colors, Barbieri and Sylvian used only the Prophet 5 and the OBX, and some Roland System 700. Barbieri remembers: “We took such care over each individual sound that we got quite paranoid about all sounds being new and different. My big influence on that album was Stockhausen, especially the abstract electronic things he was doing in the late ’50s. Listen to a track like ‘Ghosts’, for example, and you’ll hear all these metal-like sounds that hardly have a pitch, yet subconsiously suggest a melody.” Questioned about why he and Sylvian used so few synths, Barbieri answers that “when you know a lot about the architectural process within a synthesizer, you can program pretty much any sound you want.” Techniques which Sylvian and Barbieri used included the use of pink and white noise from analogue oscillators that led to the characteristic breathy nature of many sounds, and the programming of much movement into the sounds, courtesy of effects like modulation, stereo panning and reverb. These effects were generally included in the sound themselves, as one of the major characteristics of Tin Drum was the extremely dry, close-up sound, courtesy of engineer Steve Nye. Barbieri assesses that creating breathy sounds with much movement isn’t so easy on digital synths, and although he did get quite involved in the programming of digital keyboards in recent years — using the PG1000 programmer with his D50 — his preference is still for analogue.

“With all these digital keyboards, when you strip away all the effects, many of the basic sounds are awful, with all kinds of digital buzzing and graininess and glitches between the waveform loops. They sound good with the effects, but you can’t use them in a track because they take up too many frequencies. Whereas with analogue synths you’re working with a pure wave form. You start with a purity that you can affect as you go along.”

Like Sylvian, Barbieri always programs his own sounds. A preference he’s maintained from the early ’80s is for organic, low-grade sounds: “I don’t do a lot of sampling. I work in a very primitive way, putting interesting cassettes with things like choirs or didgeridoo through my Roland System 700 — it can take outside sources — and synthesizing them.”

The monophonic 700 is one of the analogue sound sources still currently used by Barbieri. Others are his untiring, MIDI’d Prophet 5, plus his Micromoog. His only digital sound sources are a Roland D50 and an Ensoniq VFX (plus the Emax HD and Emu III “for basic sampling”). He still tends to treat his sounds heavily after programming: favourite devices for creating movement are his Roland SBF325 stereo flanger and Roland SDE3000 digital delay. Other effects come courtesy of Lexicon PCM70, Yamaha SPX90II, and Korg SRV reverbs, Sound City distortion pedals, and a stereo ring modulator which he had custom built. Again, like Sylvian, and still harking back to Tin Drum times, Barbieri prefers the sound of keyboards recorded to tape (the Fostex E16), and so, oddly for a modern keyboard player, doesn’t own any sequencer or computer.

Richard Barbieri recently played on Mick Karn’s solo album, Bestial Clusters, and is involved with Karn and Jansen in their mail-order record company Medium Productions, which recently released their collaborative album Beginning To Melt (see SOS December ’93, page 20).

RECORDING THE FIRST DAY

The job of editing and structuring the pieces on The First Day was largely down to Sylvian and Bottrill. Fripp hadn’t expected to write material in the studio, found the two David’s attention to detail rather laborious and ended up coming in only when he was needed, in effect leaving the production to Sylvian and Bottrill. Sylvian stresses Bottrill’s role in the case of ‘God’s Monkey’ and ‘Darshan’. On the latter, some of Bottrill’s samples were used to form the basic rhythm, and Bottrill also devised the basic rhythm for ‘God’s Monkey’ from looped samples of Jerry Marotta practising. Sylvian: “I can’t remember much more than that Bottrill had a Roland sampler in his rack, with a Korg A2 for treatments and Performer and a Mac for sequencing. He had recorded some of Jerry’s improvisations whilst he was tuning up on DAT, edited them in the Roland and came up with this fantastic groove.” Sylvian, probably because of his emphasis on content over form, appears reluctant to divulge too much about the nuts and bolts of the recording process. He does, however, reveal that mastering is one of the most important stages of creating an album for him. “I think it’s an enormously important last step. I spend a lot of time on it, listening to the cuts on different sound systems and different speakers.

“This album was difficult to cut. It was cut seven or eight times before I deemed it passable. I felt that some of the sounds on the mixes were rather muddy, with a lot of flapping bottom end that wasn’t necessary. So we tried to bring in clarity and edge. I don’t find that mastering has become easier with CD. CDs are a blessing because it made me want to cry to have spent three months in the studio on a certain sound, and then have it masked by the surface noise of vinyl. The quality of CD is wonderful, but it’s still as difficult to come out of the mixing stage and tighten things up and create an overall sonic continuity for an album.”

Sylvian laughingly pleads his igorance about the whole MIDI scene, adding that MIDI was used very little in the making of The First Day: “My keyboards went straight to tape. We really only used MIDI and samples in the percussion department, and the orchestration in the coda from ‘Firepower’, which is culled from various sources: recordings from short-wave radio, samples from various forms of classical music — there’s a little sampled string quartet in there. There are also not a lot of keyboards on the album. I played a Fender Rhodes, Hammond organ, a Korg M1, and most importantly, a Korg Wavestation A/D. I spent a lot of time programming the A/D, as I still like to program my own sounds. Presets are simply too recognisable for a musician. It irritates me when I can recognise sounds on other people’s records.”

The singer explains that he finds MIDI “far more useful in a live context. I had Prince’s keyboard tech come in and advise me for the live rig, and that was of great help. So I got myself Opcode’s Studio 5, which was incredibly flexible for re-routing and programming when we did the tour. I found it the most flexible and accessible MIDI patchbay I’ve worked with. I also got myself a Roland JD990, which I enjoy and a Mackie CR1604 mixing desk. David was using that in the studio to put his gear through. It’s a good little board. I’m at the moment building a studio with Ingrid in the attic of our house here in Mineapolis and we’re just about to invest in a decent studio setup, based around an Amek desk.”

David Sylvian: Recording Tin Drum & The First Day