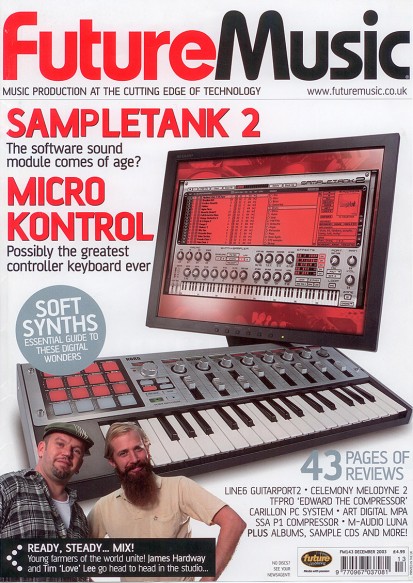

Future Music interview (nov/dec 2003, issue 143) by Danny Turner 2003 Future Music. Republished with kind permission of Future Music Magazine.

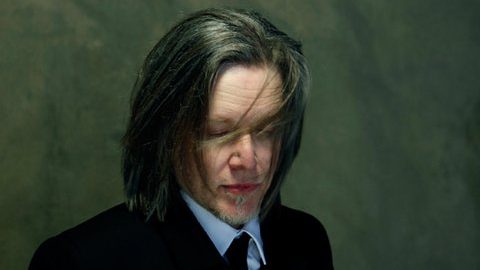

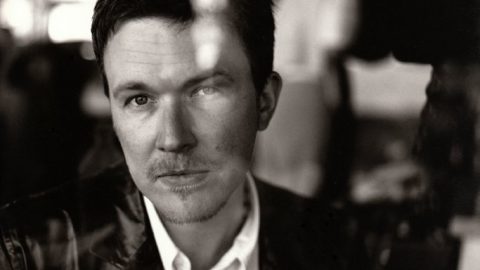

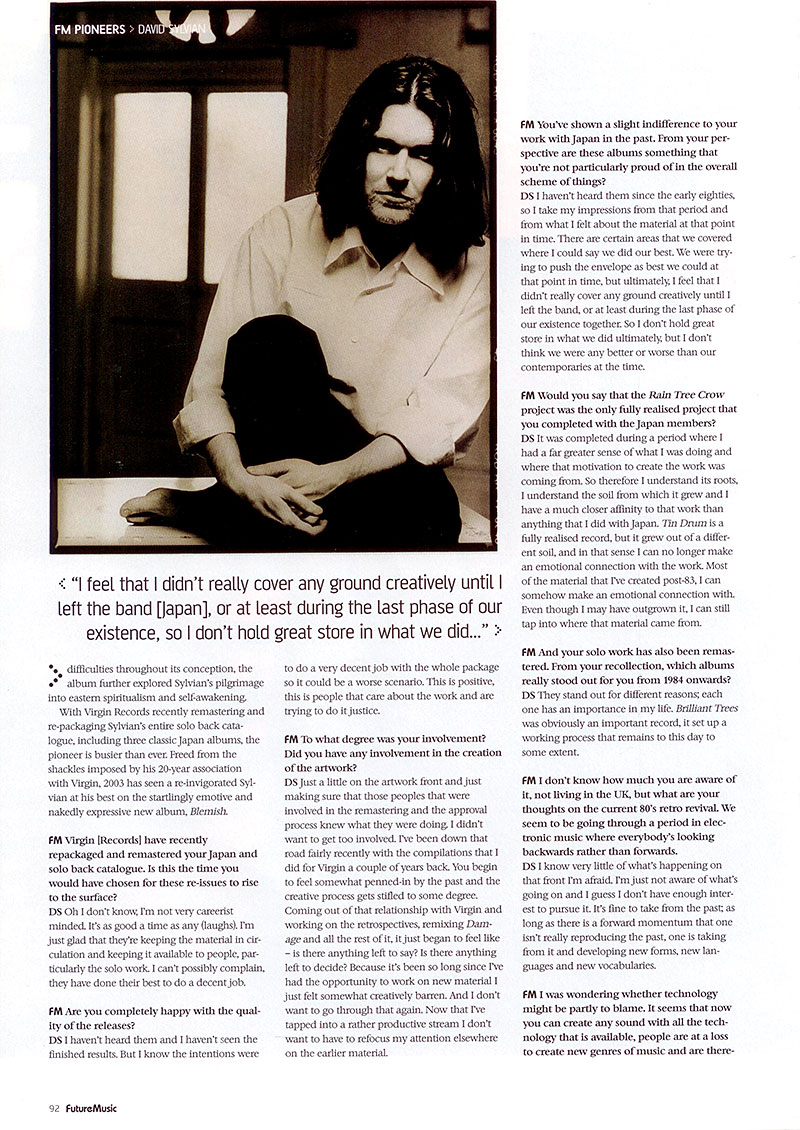

After 25 years in the music business, few recording artists today can match David Sylvians reputation as a musician of such considerable integrity and credibility.

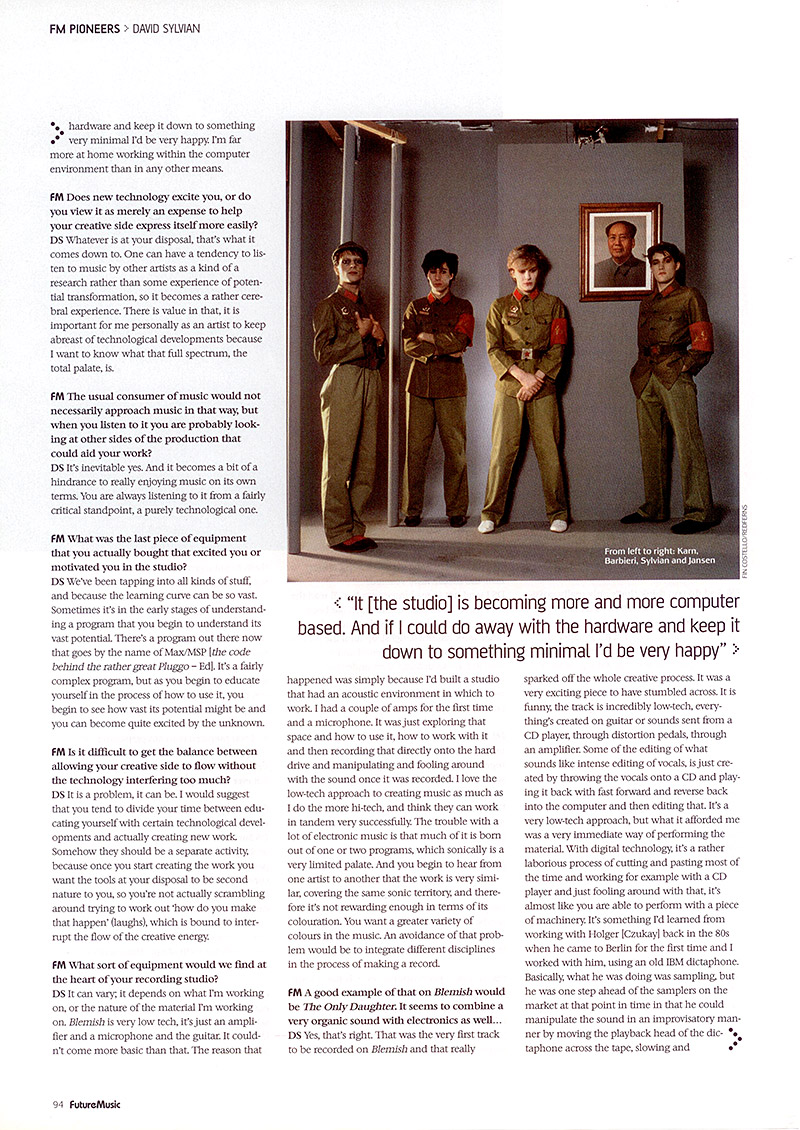

Still identifiable as the lead singer and glamorous pin-up boy for British electronic act Japan, Sylvian – along with Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri and Steve Jansen – were very much a part of the early eighties synthesiser revolution.

Today, Japan are fondly remembered for being one of the few eighties bands that successfully managed to conglomerate style and substance. The heady combination of Jansens eastern-influenced drum patterns, Karns sublime bass playing, Barbieris synthesiser washes and Sylvians charismatic vocal tones were simply unique, and the perfect antidote to the spiralling decadence of the New Romantics.

The band split at their peak in 1982, after their fifth and final album Tin Drum, amid much acrimony. Sylvian remains reticent to speak of his period with Japan with as much glowing enthusiasm as those who remember their music. This is not due to imagined personal conflicts within the group, but more to do with what Sylvian regards as the mutual exclusivity of growing up as an artist and individual at that time.

After the split, Sylvian lost little time in establishing a solo career. 1984 sawthe release of Brilliant Trees, an album of shady introspection that moved awayfrom Japans semi-commercial roots, mixing Sylvians passion for electronic pop with a far more experimental palate of sounds and ideas. He then continued with a series of astounding releases. In 1986, Gone To Earth evoked further spiritual introspection, via a richly textured exploration of free form jazz and electro-acoustic ambience, while 1987s Secrets Of The Beehive was a songwriters dream, full of intense poetic lyricism and lush orchestration.

Collaborations with Ryuchi Sakamoto, Holger Czukay and Robert Fripp then followed; usually met by a mixture of either bewilderment or astonishment, depending on which side of the fence you sat. Meanwhile, 1991 saw the brief reincarnation of Japan as Rain Tree Crow, an album that saw the full realisation of the groups collective potential.

After meeting and later marrying singer and actress Ingrid Chavez in 1992, Sylvian uprooted to Minneapolis, where the pair devoted themselves to Hindu mysticism and brought up their three children. Therefore, it wasn’t until 1999 that Sylvian’s solo career re-ignited with the album, Dead Bees On A Cake.

Fraught with difficulties throughout its conception, the album further explored Sylvians pilgrimage into eastern spiritualism and self-awakening. With Virgin Records recently remastering and re-packaging Sylvians entire solo back catalogue, including three classic Japan albums, the pioneer is busier than ever. Freed from the shackles imposed by his 20-year association with Virgin, 2003 has seen a re-invigorated Sylvian at his best on the startlingly emotive and nakedly expressive new album, Blemish.

FM: Virgin [Records] have recently repackaged and remastered your Japan and solo back catalogue. Is this the time you would have chosen for these re-issues to rise to the surface?

DS: Oh I dont know, Im not very careerist minded. Its as good a time as any (laughs). Im just glad that theyre keeping the material in circulation and keeping it available to people, particularly the solo work. I cant possibly complain, they have done their best to do a decent job.

FM: Are you completely happy with the quality of the releases?

DS: I havent heard them and I havent seen the finished results. But I know the intentions were to do a very decent job with the whole package so it could be a worse scenario. This is positive, this is people that care about the work and are trying to do it justice.

FM: To what degree was your involvement? Did you have any involvement in the creation of the artwork?

DS: Just a little on the artwork front and just making sure that those peoples that were involved in the remastering and the approval process knew what they were doing. I didnt want to get too involved. Ive been down that road fairly recently with the compilations that I did for Virgin a couple of years back. You begin to feel somewhat penned-in by the past and the creative process gets stifled to some degree. Coming out of that relationship with Virgin and working on the retrospectives, remixing Damage and all the rest of it, it just began to feel like ? is there anything left to say? Is there anything left to decide?

Because its been so long since Ive had the opportunity to work on new material I just felt somewhat creatively barren. And I dont want to go through that again. Now that Ive tapped into a rather productive stream I dont want to have to refocus my attention elsewhere on the earlier material.

FM: Youve shown a slight indifference to your work with Japan in the past. From your perspective are these albums something that youre not particularly proud of in the overall scheme of things?

DS: I havent heard them since the early eighties, so I take my impressions from that period and from what I felt about the material at that point in time. There are certain areas that we covered where I could say we did our best. We were trying to push the envelope as best we could at that point in time, but ultimately, I feel that I didnt really cover any ground creatively until I left the band, or at least during the last phase of our existence together. So I dont hold great store in what we did ultimately, but I dont think we were any better or worse than our contemporaries at the time.

FM: Would you say that the Rain Tree Crow project was the only fully realised project that you completed with the Japan members?

DS: It was completed during a period where I had a far greater sense of what I was doing and where that motivation to create the work was coming from. So therefore I understand its roots, I understand the soil from which it grew and I have a much closer affinity to that work than anything that I did with Japan. Tin Drum is a fully realised record, but it grew out of a different soil, and in that sense I can no longer make an emotional connection with the work. Most of the material that Ive created post-83, I can somehow make an emotional connection with. Even though I may have outgrown it, I can still tap into where that material came from.

FM: And your solo work has also been remastered. From your recollection, which albums really stood out for you from 1984 onwards?

DS: They stand out for different reasons; each one has an importance in my life. Brilliant Trees was obviously an important record, it set up a working process that remains to this day to some extent.

FM: I dont know how much you are aware of it, not living in the UK, but what are your thoughts on the current 80s retro revival. We seem to be going through a period in electronic music where everybodys looking backwards rather than forwards.

DS: I know very little of whats happening on that front Im afraid. Im just not aware of whats going on and I guess I dont have enough interest to pursue it. Its fine to take from the past; as long as there is a forward momentum that one isnt really reproducing the past, one is taking from it and developing new forms, new languages and new vocabularies.

FM: I was wondering whether technology might be partly to blame. It seems that now you can create any sound with all the technology that is available, people are at a loss to create new genres of music and are therefore constantly looking backwards rather than forwards?

DS: Youd think the reverse should be true, that if you have the ability to create any instrument you care to from your imagination, that you might well be creating new forms in the process. It is certainly a possibility, that its the limitations of our imagination that dont allow that to happen. I think were pretty done with certain forms of popular music, they have run their course and they no longer have the currency that they once had. Theres plenty of popular music that was once very powerful, that had the ability to move us, to uplift us, to take us to different places emotionally. Im personally finding that even very potent forms of popular music no longer have that ability to transport me.

FM: Maybe the pop song itself?

DS: Yes, its quite possible. Its run its course in that the form is over-familiar. And theres nothing left to be done with it, other than to abandon it and find new forms to deal with the same subject matter but with a whole new vocabulary that speaks to us today. We tend to turn to these earlier forms with a sense of comfort, familiarity and nostalgia, but it doesnt necessarily move us to the same degree that it once did, or at least thats what Im finding. Part of the impetus that created Blemish was to attempt to find a personal vocabulary to once again create a form of music that can have an impact.

FM: And do you think thats only really possible through the articulation of an artists individual expression?

DS: Thats certainly part of it. Its a matter of finding a new vocabulary, whether were talking about the poetry of the lyric writing, or were talking about the actual structure, the form of the song itself. With Blemish I ducked that issue by making the form very much open-ended. But I think its possible to work within much tighter parameters and still create work that has that potency.

FM: Blemish is obviously an intensely personal body of work. Ive read you say that you find it difficult to speak about the content of the work verbally, as opposed to the dropping of lyrical clues in the work itself. Why do you think that is?

DS: Yes, thats true. I could not stand more naked in my work if I tried and that is about as far as I want to go. I dont really think it is relevant that people know all the details behind the creation of the work, its all there, and its all present in the work.

FM: Its been particularly well received by the music press, are you one for reading reviews?

DS: I didnt read reviews for many years, and then when I released Everything And Nothing, I decided I would read everything for a time, just to glean an understanding of how the work is perceived and received in the world.

FM: And whats your overall feeling about how the media have reacted?

DS: I tend not to read interviews but Ill read the reviews. As far as I can tell, Blemish has been embraced critically in a way that most of my other work has not [laughs], up until the present time. It seems to be well received and people tend to have something of an understanding of what I was trying to achieve. I must admit I was very surprised by how well received it has been. I didnt anticipate that.

FM: I read you once say you were bewildered by your cultural invisibility. Do you feel regret or a sense of incompleteness if your work is not listened to by more people than you would like it to be?

DS: Its really hard to be objective regarding the relevance or irrelevance of the work that one has produced. But the attempt is to communicate the work and to create to as large an audience as possible, no matter how obscure the work may or may not be on the surface. So, yes I would always wish there was a larger audience out there for the material that I was creating, and maybe the fault is on my side, that I am failing to communicate successfully in my work on a level that many other people can engage in.

FM: And on a promotional level, is there some feeling that you might struggle to reach more people now that youre on your own label [Samadhi Sound]?

DS: The expectations arent quite as high. When youre working with a major label you expect them to put a great deal of effort into promoting the work that theyve taken on board. That so often wasnt the case with Virgin, particularly in the latter stages of my relationship with them. So there was a sense of frustration there. I was signed to a major label my entire adult life, so I was afforded a security of some sort in that relationship, but there was enormous frustration too. Having separated from Virgin, theres no real desire to rush back into another relationship with a major label. I just wanted to explore that new found sense of freedom and liberation, and was prepared (and am prepared) to work on that smaller scale as a result of not having that massive machinery working at my disposal, if it ever was (laughs).

FM: Have you become aware of the vast changes of music technology over the years?

DS: Sure, yes, because it adds to the vocabulary or the possibilities, the potentials. Actually, the past year or so has been quite a vast learning curve in terms of getting to grips with new technology. And its evolving all of the time and you can get into a bit of a trap with that, just constantly trying to keep up with whats going on. But as long as you have a fair level of competence with the technology, I think thats enough to sustain you and enable you to work with it.

FM: And do you regularly update your studio equipment to keep-up with the latest advances in technology?

DS: Sure, its becoming more and more computer based. And if I could do away with all hardware and keep it down to something very minimal Id be very happy. Im far more at home working within the computer environment than in any other means.

FM: Does new technology excite you, or do you view it as merely an expense to help your creative side express itself more easily?

DS: Whatever is at your disposal, thats what it comes down to. One can have a tendency to listen to music by other artists as a kind of a research rather than some experience of potential transformation, so it becomes a rather cerebral experience. There is value in that, it is important for me personally as an artist to keep abreast of technological developments because I want to know what that full spectrum, the total palate, is.

FM: The usual consumer of music would not necessarily approach music in that way, but when you listen to it you are probably looking at other sides of the production that could aid your work?

DS: Its inevitable yes. And it becomes a bit of a hindrance to really enjoying music on its own terms. You are always listening to it from a fairly critical standpoint, a purely technological one.

FM: What was the last piece of equipment that you actually bought that excited you or motivated you in the studio?

DS: Weve been tapping into all kinds of stuff, and because the learning curve can be so vast. Sometimes its in the early stages of understanding a program that you begin to understand its vast potential. Theres a program out there now that goes by the name of Max/MSP [the code behind the rather great Pluggo – Ed]. Its a fairly complex program, but as you begin to educate yourself in the process of how to use it, you begin to see how vast its potential might be and you can become quite excited by the unknown.

FM: Is it difficult to get the balance between allowing your creative side to flow without the technology interfering too much?

DS: It is a problem, it can be. I would suggest that you tend to divide your time between educating yourself with certain technological developments and actually creating new work. Somehow they should be a separate activity, because once you start creating the work you want the tools at your disposal to be second nature to you, so youre not actually scrambling around trying to work out how do you make that happen (laughs), which is bound to interrupt the flow of the creative energy.

FM: What sort of equipment would we find at the heart of your recording studio?

DS: It can vary; it depends on what Im working on, or the nature of the material Im working on. Blemish is very low tech, its just an amplifier and a microphone and the guitar. It couldnt come more basic than that. The reason that happened was simply because Id built a studio that had an acoustic environment in which to work. I had a couple of amps for the first time and a microphone. It was just exploring that space and how to use it, how to work with it and then recording that directly onto the hard drive and manipulating and fooling around with the sound once it was recorded. I love the low-tech approach to creating music as much as I do the more hi-tech, and think they can work in tandem very successfully. The trouble with a lot of electronic music is that much of it is born out of one or two programs, which sonically is a very limited palate. And you begin to hear from one artist to another that the work is very similar, covering the same sonic territory, and therefore its not rewarding enough in terms of its colouration. You want a greater variety of colours in the music. An avoidance of that problem would be to integrate different disciplines in the process of making a record.

FM: A good example of that on Blemish would be The Only Daughter. It seems to combine a very organic sound with electronics as well

DS: Yes, thats right. That was the very first track to be recorded on Blemish and that really sparked off the whole creative process. It was a very exciting piece to have stumbled across. It is funny, the track is incredibly low-tech, everythings created on guitar or sounds sent from a CD player, through distortion pedals, through an amplifier. Some of the editing of what sounds like intense editing of vocals, is just created by throwing the vocals onto a CD and playing it back with fast forward and reverse back into the computer and then editing that. Its a very low-tech approach, but what it afforded me was a very immediate way of performing the material. With digital technology, its a rather laborious process of cutting and pasting most of the time and working for example with a CD player and just fooling around with that, its almost like you are able to perform with a piece of machinery. Its something Id learned from working with Holger [Czukay] back in the 80s when he came to Berlin for the first time and I worked with him, using an old IBM dictaphone. Basically, what he was doing was sampling, but he was one step ahead of the samplers on the market at that point in time in that he could manipulate the sound in an improvisatory manner by moving the playback head of the dictaphone across the tape, slowing and speeding up the tape as he played. So there was a performance element to what he was doing which was very much part and parcel of the quality of what we finally got on tape.

FM: So quite an artistic way of working, almost like painting, where you are messing around with the colours?

DS: Exactly, letting go of control is so much a part of the creative process; always trying to keep a firm grip on the wheel will guarantee limited results.

Maybe the limitation with digital technology as it currently stands, is that there isnt enough room for that performance element to come into play. Its there, and its growing all the time, but sometimes you have to compensate, or at least I felt that I did.

FM: The guitar has always played a prominent part in your work and you quite often process the sound of the guitar so that its hard to differentiate it between synthesised sound. Why do you choose to use the guitar in that way instead of using the keyboard or programme sounds?

DS: Well just because it is another tool at my disposal. Maybe its the instrument Im most fluent with as a player. Often when you work with guitars youre working with amplification, theres actually molecules bouncing around. It creates a different grain to the overall texture of the sound that youre able to achieve.

FM: Do you find therefore that digital recording can sometimes be a bit too clean?

DS: Well theres a beauty to that, and certainly thats something I can appreciate. As you can hear, many of the people working with digital technology are trying to dirty it up all the time in new and interesting ways. For me it has always been a matter of anything goes. Whatever works, use it. Im not much of a purist; Ill take elements from all different sources and try to create as interesting a hybrid as I can.

FM: Maybe this explains why a lot of artists are actually going back to using analogue keyboards now, maybe because they have a much dirtier feel to them than digital?

DS: Yeah, maybe its something they didnt have to hand first time around, so its interesting for them to go back and grapple with the instruments, and just be very hands-on with technology can be very gratifying.

FM: So when you start recording a track, do you sometimes use sound as a source for creativity as opposed to using the mind as a creative centre?

DS: Something can be sparked by sound sure. Generally, Ill carry an idea for a work around with me for sometime. I think of it as a gestation period. Its a very intangible experience, but its living with an understanding of what the work might potentially be without ever actually giving it form mentally.

FM: Are these stored-up emotions?

DS: I think they are related to emotions and theres a sense that something needs to be said and youre not quite sure what it is. And you dont want to have any greater understanding of it at that moment in time. You want to let it gestate and mature to a point where it tells you what it is, and how it should sound and what form it should take. And during that period of gestation, certain sounds, certain elements, maybe in the work of others or maybe just in my own imagination, will come to mind as being relevant to that particular body of work that wants to take form.

FM: And then do you just have an impulsive feeling to go into the studio and release all that content?

DS: Yes, and there will be certain sounds that I already know are going to be part of its vocabulary. So Ill look for those sounds, and on discovering them then you open the floodgates and something starts to come through.

FM: I understand that youve recently completed a track with Ryuichi Sakamoto?

DS: Actually it was an odd process of development. Ryuichi started out working on what he called chain music in response to the oncoming war in Iraq and he started sending this material around to a number of musicians. He wanted to send it to me with a view to my writing an anti-war lyric for the project. I felt that maybe the weighty subject matter was beyond my reach and not something I really wanted to grapple with at that point in time. But, while I was travelling I came up with the beginnings of an idea for an anti-war piece. The title World Citizen came to mind. On my return to the States the chain music was waiting for me, I responded to it by just repeating the word World Citizen and while I was doing that a fuller lyric was coming to mind. So, I came up with this composition, sent it to Ryuichi to see what he thought and there was a kind of muted response. It wasnt what he was expecting; it was a bit full-on lyrically. He wrote back and said he loved the concept of World Citizen, asked if we could try and find a more pop approach to the same material. Ryuchi sent me a one note piano loop and I wrote a new piece to that, which he then sent-off to the ex-members of YMO, who are currently working under the name, Sketch Show. They made a big contribution to the track and Ryuichi finally finished up the piece himself. So, that piece is called World Citizen (I Wont Be Disappointed). He called me while he was working on that and said lets record that other song that you wrote too. One is a very electronic-based piece of music, very much in keeping with what people might perceive as YMOs kind of pop composition territory. The other piece is a little grungier, a little bit more rock based.

FM: And whens this likely for release?

DS: Its coming out in Japan towards the end of October, but theres no known release date yet.

FM: And is working with Ryuichi something that youll be looking forward to doing again at some point in the future?

DS; Id work with Ryuichi anytime. Its a great relationship. Its one of these collaborations that go on regardless of the fact that we never really have any future plans to work with one another. When a collaboration ends there is no talk of the next, but somehow the ball keeps rolling and it remains interesting. Funnily enough, a connection seems to occur at pivotal points in either one of our developments I think.

FM: You have done quite a few collaborations with other artists where you are sending music from one country to another via a computer. Do you not lose something by not being with them in person when working on the compositions?

DS: I dont think it makes an awful lot of difference, surprising as that might sound. There is a challenge to it and a freedom to working in that fashion. It can fall flat just as it can fall flat with a room full of musicians working with one another. I mean when Ryuichi and I started working together back in the early eighties we had no means of communicating verbally really, there was a language barrier. And all the communication that really worked was musical. He would play something, he’d see recognition in my face and vice versa and we’d move on that level, there was no need for dialogue.

FM: Are there any other projects you are currently working on, and can we now expect slightly more frequent releases from you in the future?

DS: Yes, I hope so. I made another contribution to Chris Vrenna’s new work (Tweaker). I’m attempting to get some work done with Christian Fennesz. But unfortunately I’m so busy with the tour I hope I’m not going to run out of time on that one. But that’s definitely a collaboration I want to pursue.

FM: How is it working with your brother, Steve Jansen?

DS: We are currently working on new material together; We’ve been at that for a while. That was put on hold, during the period I was recording Blemish, but because Blemish seemed to take-off in a way I hadn’t anticipated. It sort of drew me away from the studio for a while. I’m encouraging Steve to work on his first solo album, so there will ultimately be a Samadhi release. And then just working with the label, just trying to understand its potential for both myself and other artists. It’s an interesting time; one of the concerns about starting my own label was that I’d have to wear the business hat too often for my liking. But I find that the business level can be equally creative. Working with Virgin was often far more frustrating and exhausting on a business level than working with my own label where there’s now a free flow of energy.

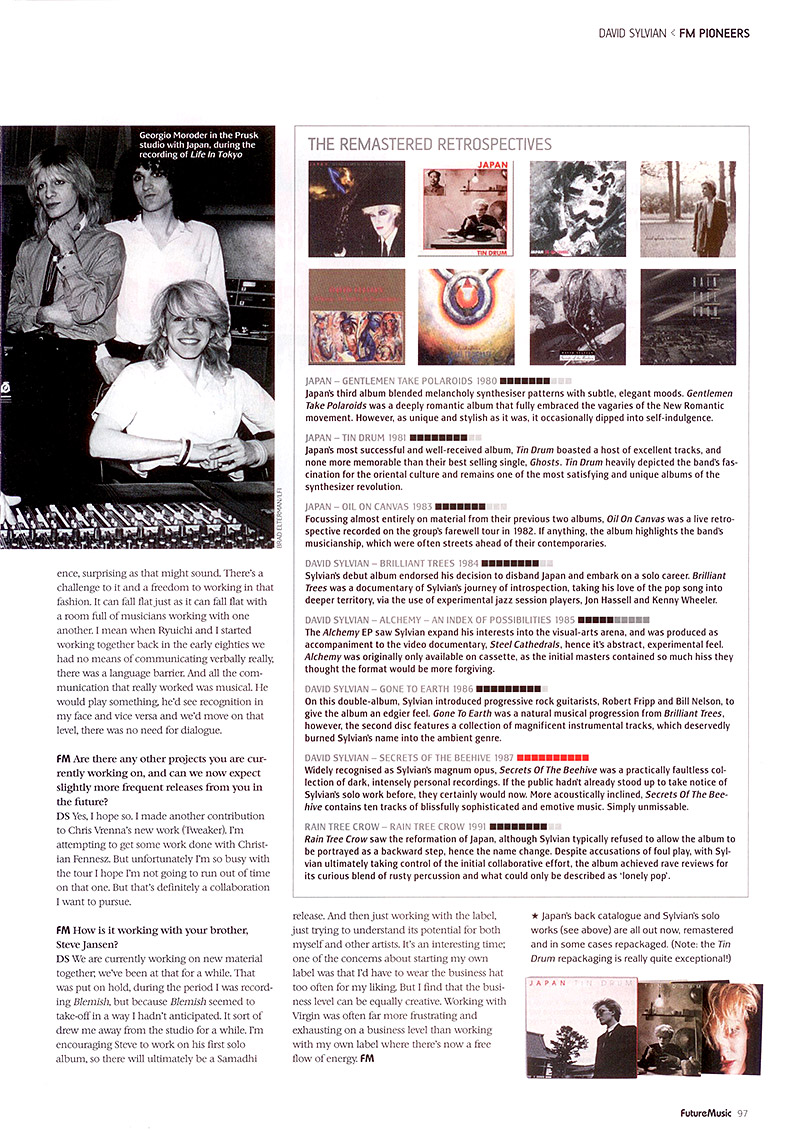

Japan’s back catalogue and Sylvian’s solo works (see above) are all out now, remastered and in some cases repackaged. (Note: the Tin Drum repackaging is really quite exceptional!)