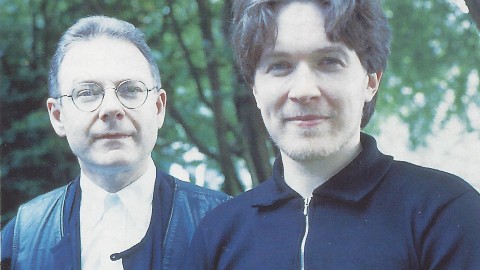

David Sylvian: The Loner Emerges

by Ted Drozdowski, Musician, May 1988

JAPAN’S RECLUSIVE LEADER FINDS TECHNO-POP MATURITY IN A SOLO AFTERLIFE

“MY MUSIC,” says songwriter, singer and keyboardist David Sylvian, “provokes introspection, which allows individuals to find answers within. I think people who find my work uncomfortable or depressing are the kind who find it difficult to sit in a room alone, because there are elements within themselves that they are very uncomfortable with. For that reason, I think of my music as geared to very small pockets of people who are very comfortable with themselves.

“I can be a very easy target for any journalist who wants to take me up,” he continues. “My work is very fragile, if you like. It can be ridiculed very easily, but it has an inner strength. A lot of people don’t want to see that. Especially men, because there is a very feminine quality to my work that a lot of men feel uncomfortable being moved by. It’s too delicate for them, too sensitive.”

Obviously Sylvian’s not the kind of guy who writes silly love songs. But rays of hope and redemption do shine through his cloudy, minor-key romanticism. His first band, the art-pop group Japan, was an eight-year exercise in self-discovery. Since its dissolution in 1982, Sylvian has slowly, and often painfully, continued to strip off the mask he’d fashioned for himself. In the course of three solo albums, he’s neatly abandoned the conventions of techno-pop to make music that weds the raw elements of jazz, classicism and free expression with the hoariest and most honorable of song forms, the ballad. But he’s one balladeer who’ll never sound like Dylan. His songs are more like whisperings carried on a warm night wind that twists its way across the darkened Saharas of the soul.

Not easy stuff to convey, yet Sylvian’s midnight messages reach their target. His 1986 solo album, Gone to Earth, which featured the blazing guitars of Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson, was such a success as an import that the Virgin label released the two-disc set domestically the moment it opened U.S. offices last year. Sylvian’s recent Secrets of the Beehive, a quieter work, got a similar reception from fans and, like Gone to Earth, has begun the long trek from the underground via college, alternative and even new age radio play. But the most promising sign of Sylvian’s increasing popularity is his recently completed tour of North America, the Far East and Europe, his first since Japan’s final foray.

As a sensitive, working-class kid growing up in a rundown southeast London suburb, Sylvian “found the world a very insensitive place to be.” At 29, he still paints his childhood as “a painful experience, with a lot of memories I’ve purposefully buried away.” He was an aspiring hermit until Smokey Robinson, the Supremes and Marvin Gaye pried their way into his adolescent life, and he and his brother, Steve, started writing songs on guitars they’d gotten from their parents.

“Being the kind of kid that liked to spend a great deal of time alone, it was inevitable that I would find a kind of companionship in music,” he says. He also found new companions. The first was Anthony Michaelides, who picked up the bass to join the brothers’ furtive jams. Then came Richard Barbieri, who’d had a few piano lessons and was therefore drafted to play keyboards. Thus, in 1974, the boys formed the nucleus of Japan.

The band went nameless while they learned to play, and was hastily baptized for their first gig. “The name Japan meant next to nothing to us. We figured, ‘It’ll do for tonight,'” Sylvian recalls. “And it just stuck. We tried to change it later on, but it was too late.”

By 1977, when the band won a talent contest sponsored by the Hansa label, Sylvian had stopped using his given surname, Batt, and taken refuge beneath a nest of peroxide blonde hair and the trappings of glam-rock. His brother followed suit, switching his last name to Jansen and his instrument to drums. Bassist Michaelides metamorphosed into Mick Karn, Sylvian’s main musical foil. “At the time,” Sylvian explains, “I was trying to escape from myself, so the music and the look was something to hide behind, to give me the strength to go on performing in public.

“Our record company had signed the band solely on image, and we had a manager who was trying to mold us, who wanted creative input. He came from the ’60s, and his idea was to shock people, to be as outrageous as possible. But that period was already gone.”

Japan’s first albums, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives, were flung loose amidst a hurricane of hype in 1978. Today Sylvian cringes at their mention. “We were slagged off, quite rightly. It was bad music,” he says, nervously twirling some stray shoulder-length strands of hair — now naturally brown.

Actually, those records weren’t so bad. Sylvian’s discordant, thrashy songs brimmed with strange, simmering passions, and he and Rob Dean managed some amiably scrappy guitar work. And there were signs of better things to come in ‘The Tenant’, Obscure Alternatives’ moody, piano-based closing track.

“That was the first time I’d sat down at a piano,” he says. “I started writing on the keyboard after that, and it made a dramatic change in the music. Some of it became far more melodic, and I began to understand more about chord structures. The music took on a quieter side, but, nonetheless, I still don’t think I was expressing myself. I don’t think I found myself in music until I wrote ‘Ghosts’.”

That would be three albums later. First the band had to work hard to reclaim its self-esteem. Most of 1979 was spent rethinking its musical approach and making Quiet Life, which had fewer rough edges, a newfound rhythmic flexibility and brought keyboards to the fore. Next came a change of labels, to Virgin, and Gentlemen Take Polaroids, whose title single and ‘Methods of Dance’ were Japan’s first successes at home.

Japan’s mannered music became increasingly textural and complex as Sylvian and Barbieri delved deeper into technology, immersing themselves in synthesizer programming and mastering the secrets of the studio. Sylvian found a sympathetic ally in Ryuichi Sakamoto, founder of Japan’s answer to Kraftwerk, the Yellow Magic Orchestra. Sylvian and Sakamoto had met during one of Japan’s trips to — where else? — Japan, and coincidentally found themselves working at the same English studio complex while Gentlemen Take Polaroids was being recorded. Sakamoto joined in the sessions, playing keyboards and writing several songs with Sylvian.

Working with Sakamoto led Sylvian into new compositional turf, and the result was Tin Drum. “Richard and I were working with the synthesizers, developing sounds, and it just got to an extreme where we began writing songs based on sounds alone,” says Sylvian. “I had an idea, which was to cut every alternate melody line down to its essential notes, and split those melodies into as many fragments as possible, and then record each of them with different sounds. It was a very Japanese idea — to leave as much space in the music as possible. I think we explored that well on ‘Talking Drum’ and ‘Cantonese Boy,’ the first songs we recorded that way. When we saw where that was going, we decided to continue, and the whole album was based on that principle.”

Stardom was the reward for Tin Drum’s experimentation, and the album became an acknowledged pop masterpiece. It put Japan at the top of the U.K. charts in 1981 and cemented its reputation in the Land of the Rising Sun, where even the first two albums had been hits — for obvious reasons. But for Japan, stardom “came so late that we had already grown tired of the idea,” Sylvian recounts. “That sounds very arrogant, but I think that if it had happened earlier we would probably have enjoyed it more. Obviously we were pleased to be selling records, but we were aware that the majority of the audience was just attracted to the fashionable side of pop music. We looked right, we sounded right, and we had that new audience for those reasons. I never really felt good about that. I still don’t.”

Caught in the tailwind of the new-romantic fad, Sylvian was pampered by the press and primped by his label. “I was left with the feeling that I wasn’t doing anything important — that the person they were writing about wasn’t me, it was an image, and that any real quality in the music was being buried so deeply beneath that image that nobody was seeing it. I wanted the music to exist as itself, not for me to stand in front of it and dilute its message. So I slowly crept into the background.”

He stayed there for nearly two years. First, Japan disbanded: “We’d had an unspoken rule that nobody would work on solo projects while the band existed, to create a kind of tension within the group,” Sylvian explains. “That forced all creative ideas to go into the group, and made for a more intense quality. Mick suddenly decided to make a solo album. We’d just made Tin Drum. It was a peak, so I decided to split the band — which would have happened anyway. Relationships had been strained making that album and I knew making another would be a painful experience as well.

“I stopped writing for about a year-and-a-half, because I was trying to find a means of songwriting that was more direct, and I found it very difficult. As a reaction to the frustration I felt, I went back to drawing, as I’d done when I was a child. I found a great deal of pleasure in that. It reminded me of how I used to feel about songwriting: a feeling of adventure, exploring ideas, which I’d somehow lost.” Ironically, the gentleman also began taking Polaroids, which he assembled into a book and exhibited in London, Milan, Tokyo and Turin. Those exhibitions became the subject of a video documentary Sylvian made for Japanese television. Ultimately, Ryuichi Sakamoto was the catalyst for Sylvian’s reemergence. Sakamoto was working on his sound-track for the film Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and asked his London friend for lyrics. “That forced me to write, which I’d been avoiding for some time,” Sylvian admits. He also sang on ‘Forbidden Colours’, the soundtrack’s single.

Sylvian returned to his piano and guitar, “just inventing chords, writing the way I used to as a kid.” Those homemade chords begat songs like ‘The Ink in the Well’ and ‘Red Guitar’, and were the roots of Brilliant Trees, his first solo album, in 1984. “The best thing about those chords is you haven’t a clue what they are,” he offers. “It’s like working in the dark. You just sit and listen, searching for what’s correct.”

“I must admit,” says horn player/composer Mark Isham, who’s worked with Sylvian since Brilliant Trees, “that there’s been a couple of times when it’s taken me a while to figure out what the hell he’s doing. The changes on ‘Red Guitar’, for example, are very complex and non-traditional. There are certain accepted orders of chord relationships that most all music has, but this piece goes against all of those, and that gives it a wonderful mood and sense. But it was very, very difficult to learn.”

The drafting of players like Isham and Kenny Wheeler for Brilliant Trees was a mark of Sylvian’s growing passion for jazz. “I’d been listening to a lot of the ECM artists for the first time, and had caught up on the Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans thing, and wanted to bring some of that feeling of immediacy into my work,” he says. “In Japan, we were self-taught, but none of us could really improvise. I still can’t, which is why I tend to give soloists lots of room.

“I’m not a good keyboard player, or guitarist for that matter, and if I allow myself to play on my own records it’s because there’s a quality in my playing that I don’t think can be produced by someone who’s more technically proficient. I like the idea of being an eternal amateur and allowing that to show through. It’s very direct, very honest.”

Brilliant Trees was a cult smash in Britain, but was never released in the States. Still, it caused a buzz in the underground here that intensified as bootleg copies of Sylvian’s documentary on the Polaroid exhibits began circulating. Sylvian decided to re-edit that film to release a shorter, authorized version in Britain. Unsatisfied with its original soundtrack, he took the master tapes into a studio to rework them.

“I was having a lot of trouble with ‘On the Way’,” says Sylvian. “My main problem was looking for an instrument to solo through the track. Suddenly I thought of Robert Fripp, and I could just hear him there.” Coincidentally, Fripp was in London doing a renegade tour of local record shops. “He came in the next evening and it worked magically.

“Afterwards Robert said, ‘This has been most interesting. Do you have anything else for me?’ I said no, but I had already been working on another project with [former Be-Bop Deluxe leader/guitarist] Bill Nelson, so I started writing songs with the idea of two guitarists working against each other.” The Fripp/Nelson dichotomy can be heard on the brilliant Gone to Earth, with results that range from evocative to eviscerating.

Gone to Earth’s popularity prompted Sylvian’s first press tour, not a promising prospect for the retiring artist. Yet he returned from weeks of stumping feeling surprisingly recharged. “As soon as I got back, I started writing, and it was very, very easy. In three months I had a wealth of material and was ready to go back into the studio to record Secrets of the Beehive, which was a surprise to me. Normally it takes weeks to write a single song. The idea germinates and develops in my mind long before I’m ready to sit at a piano. But each of these songs came in one sitting.”

The songs on Secrets of the Beehive are relatively unadorned, despite the distinctive colorations of players like Sakamoto, Isham and avant-guitarist/composer David Torn, and the album’s bedrock is acoustic piano and guitar. “Due to the highly lyrical nature of these songs, I wanted to be very careful about the arrangements,” Sylvian insists. “I wanted to be sure none of the tracks lost their intimacy.”

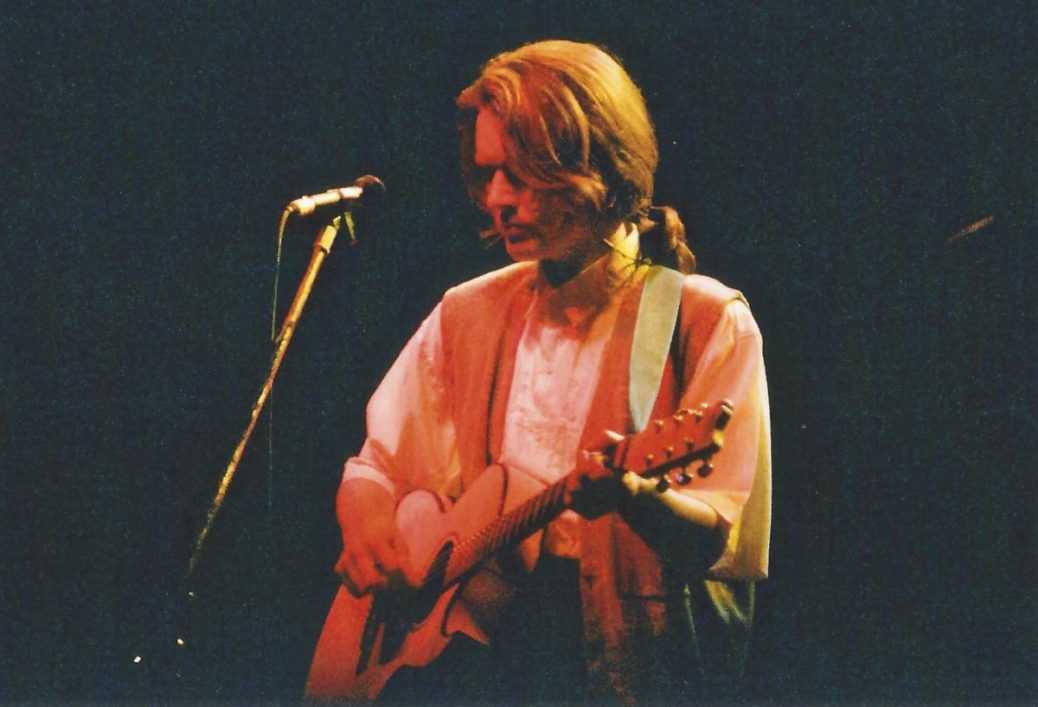

Preparing for his first solo tour at the time of this interview, Sylvian was, not surprisingly, nervous. He joked about “sorting out which songs will really work well live, which means it could be a very brief program.”

Then again, not much has been easy in Sylvian’s career. “Really, it’s been a process of becoming secure in myself and trying not to fool anybody,” he says. “You finally say, ‘This is me, this is the way I am, this is the way I play, the way I sing.’ You have to accept it, and try to put that across as openly as possible.” •

NOTES FROM THE HIVE

SYLVIAN AND his touring band don’t travel light. Sylvian’s stage keys are a Roland D-50 with PG-1000 programmer, a Prophet 5 and a Prophet VS. He strums a Fender Strat and a Washburn electro-acoustic, and sports two Yamaha SPX90IIs, an E-mu E-Max sampler and a trusty Macintosh. Richard Barbieri, also in the keyboard corner, uses two Prophet 5s, a Roland D-50 and an E-mu E-Max. His rack includes a Roland SBF-325 stereo flanger, two Roland SDE-2000 delays and an SPX90II.